Salvage Operations: Resections, Arthrodesis, Hip Disarticulations, Prostheses

Panayiotis J. Papagelopoulos

Vasileios I. Sakellariou

Christopher P. Beauchamp

Franklin H. Sim

Introduction

Salvage techniques are often considered in those with less than optimal outcome. Sometimes, surgeons may need to compromise, especially when the patient’s perioperative condition is unstable and severe comorbidities or technical difficulties exist. Resection arthroplasties, hip arthrodeses, disarticulations, and periacetabular reconstructions with the use of saddle prostheses are no more popular today as in the past. However, there remains a role for these salvage techniques.

Resection Arthroplasty

Historical Perspectives

Resection arthroplasty is often referred as a Girdlestone procedure after Mr. G.R. Girdlestone, who described in 1923 the resection of the femoral head and neck along with a lateral portion of the acetabulum for the treatment of primary tuberculosis, for pyogenic infections, and for severe unilateral osteoarthritis of the hip joint (1). However, the resection of the femoral head alone was first described by Schmalz in 1817 as a treatment for septic arthritis and Barton in 1821 as an option to mobilize an ankylosed hip (2).

Indications and Contraindications

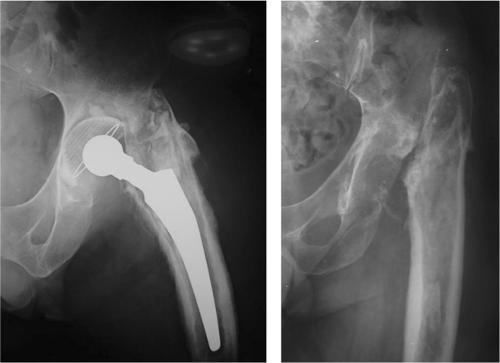

The indications for a resection arthroplasty have changed throughout the years. The main indication remains the eradication of infection in cases with septic hip arthritis or hip osteomyelitis (3,4). It may also be used as a salvage procedure for periprosthetic infections usually after multiple failed attempts for eradication of the infection. Relative indications include the management of osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, femoral neck nonunions, infected fractures, bilateral neglected hip dislocations, and protrusions (3,5). Although the role of resection arthroplasty and the range of indications have been quite narrowed since the advent of total hip replacement, it still remains a valuable option especially when trying to eradicate a hip infection and preserve joint mobility in flail patients with major comorbidities (Fig. 79.1); elderly patients, noncapable of independent mobilization, immune-compromised, intravenous drug users, and patients with limited life expectancy can be considered as possible candidates for this procedure (6,7).

Contraindications for resection arthroplasty are not clearly defined. However, obese patients and those with impaired function of their upper extremities should be better excluded, because the procedure often induces postoperative hip instability, and therefore prolonged use of external supportive devices is often needed (6,7).

Surgical Technique

An anterior (Smith-Peterson), anterolateral, or posterolateral approach to the hip can be utilized. Girdlestone originally described the procedure that was performed using a lateral approach to the hip joint through a transverse skin incision. Two parallel transverse deep incisions are made to resect the gluteal muscle just above the acetabulum. The femoral neck cut is made at the intertrochanteric line and the femoral head is resected. Although Girdlestone in his original technique described a simultaneous resection of the greater trochanter and the lateral aspect of the superolateral acetabular rim (1), later modifications tend to be much more conservative (3,5,8,9). Today, the greater trochanter is nowadays left intact to preserve the insertion of abductor muscle. This improves hip stability and makes future conversion to total hip arthroplasty feasible.

After resection of the femoral head, the avascular cartilage of the acetabulum is reamed meticulously to prevent recurrence of joint infection. The removal of capsule is

controversial. In septic cases, it is usually removed, whereas capsular interposition is preferred in noninfected hips to prevent bone-to-bone apposition and enhance the development of a functional pseudarthrosis. The wound is closed in a typical fashion over suction drains.

controversial. In septic cases, it is usually removed, whereas capsular interposition is preferred in noninfected hips to prevent bone-to-bone apposition and enhance the development of a functional pseudarthrosis. The wound is closed in a typical fashion over suction drains.

Postoperative care should maximize the potential to develop fibrotic tissue within the void of the resected femoral head. The goal is to create a stable pseudarthrosis between the acetabulum and the proximal femur while limiting the limb length inequality (5,10,11). Although prolonged traction has been advocated for many years, newer studies have not documented any significant benefit on the limitation of limb shortening, joint stability, and/or the use of supportive walking devices.

Outcomes

The procedure is not technically demanding and can offer substantial pain relief, control of infection, and functional improvement. Specifically, there are reports showing a significant reduction of hip pain from 80% and up to 100% after a successful resection arthroplasty (5,10). Most patients remain ambulatory. However, almost 90% use a crutch or a cane. The energy consumption after the procedure is increased up to 240% of normal, which is comparable to unilateral above-knee amputation. Functional outcome is moderate (3,7,8). To avoid unrealistic expectations, functional limitations should be clearly discussed in detail with the patients. Nevertheless, 70% to 90% of the patients are satisfied from the overall outcome (3,4,12).

When complete eradication of an infection is considered as the criterion of success, Girdlestone arthroplasty remains as an essential option to control septic arthritis of the hip joint. In a recent study, it was shown that Girdlestone arthroplasty was able to control infection in 96% of patients (6). Prosthetic replacement after Girdlestone arthroplasty should be individualized in every case; factors to be considered include bacterial growth, soft tissue condition, and patients’ general condition (4,6). However, conversion to total hip arthroplasty is associated with high complication rates and poor functional results (13,14,15).

Complications

Resection arthroplasty is considered a straightforward procedure, without significant perioperative complications. However, patient satisfaction is not always optimal because of significant leg length discrepancy, dependency on supportive

devices for ambulation, and a high probability of some persistent pain (9). Shortening between 2.5 and 5 cm is considered “natural” for this procedure (5,7). A shoe lift can compensate for the differences in length.

devices for ambulation, and a high probability of some persistent pain (9). Shortening between 2.5 and 5 cm is considered “natural” for this procedure (5,7). A shoe lift can compensate for the differences in length.

Postoperatively, the lower limb usually has the tendency to rest in external rotation because of uneven traction of the iliopsoas muscle. Excision of the lesser trochanter or osteotomy and transfer to the anterolateral aspect of the femur have been proposed as possible solutions (6,16,17). However, both techniques may compromise future reconstruction and therefore should be avoided (6,17).

Hip instability is another common problem after resection arthroplasty. Combination proximal femoral abduction osteotomy with femoral head resection has been reported to increase hip stability (18). However, this is a more demanding procedure and femoral osteotomy necessitates fixation with a blade plate, which is not preferable in cases where the indication for surgery is infection.

Arthrodesis

Historical Perspectives

Lagrane first introduced hip arthrodesis, in 1886 for the treatment of a congenital hip dislocation, resulting in pseudarthrosis. Twenty-two years later, Albee described two different techniques, the intra-articular in 1908 and the extra-articular in 1915. Van Nes popularized the use of internal fixation to enhance stability and increase fusion rates in 1922 (2,19). However, it was in 1966 that Schneider introduced the cobra-head plate as a modern fixation device utilizing Sir Charnley’s concept of central dislocation and internal compression fixation technique, to shorten the lever arm, and subsequently lower hip joint reaction forces and promote fusion (2,19,20).

Indications and Contraindications

With the evolution of total hip arthroplasty, the role of arthrodesis is almost insubstantial nowadays (21,22,23). It is a procedure of limited acceptance by both the patients and the orthopedic surgeons. Although studies have shown that arthrodesis is compatible with a functional and productive life that meets the needs of the young active patient with a unilateral hip disease, the incomparable superiority of functional recovery after total hip replacement has almost eliminated the indications of this procedure (21,23).

Hip arthrodesis has been almost completely substituted by total hip arthroplasty in North America. The best candidate for the procedure could be a heavy laborer under the age 30 to 35 years with isolated hip arthritis. Any patient who does not intend on returning to work after the procedure is not considered a good candidate for hip arthrodesis (22).

Contraindications to this procedure should be the presence of low back pain, ipsilateral knee, and/or contralateral hip arthritis. Ipsilateral knee instability is another absolute contraindication. A relative contraindication is patients with a height over 72 in, because they may encounter significant difficulties in sitting in a limited crowded space (22).

Surgical Technique

A lateral skin incision is used extending from 7 cm proximally to 7 cm distally from the tip of the greater trochanter. The interval between the tensor fascia lata and the gluteus maximus is utilized. A trochanteric osteotomy is performed with caution not to traumatize the medial femoral circumflex vessels, which supply the femoral head. A T-shape incision is performed to open the joint capsule and the femoral head is exposed and dislocated anteriorly. Alternatively, a two-incision approach is utilized. This consists of a typical anterior Smith-Petersen approach which facilitates dislocation and bone preparation of the femoral head and the acetabulum, combined with a lateral incision, which is used to place the hardware for fixation.

Both the femoral head and the acetabulum are reamed to expose the subchondral bone using concave and convex reamers, respectively, so that the femoral head fits the acetabulum. A pelvic osteotomy can be additionally performed to provide adequate coverage of the femoral head. The ideal position for a hip arthrodesis is with the limb in 5 to 10 degrees of adduction, 10 degrees of external rotation, and 25 to 30 degrees of hip flexion. Abduction and internal rotation should be avoided. Abduction is found to be associated with more ipsilateral knee and low back pain. Internal rotation should be avoided to prevent interference with the contralateral foot during walking. Moreover, external rotation facilitates footwear when flexing the knee (19,20).

The femur is fixed to the iliac bone using a nine-hole cobra-head plate (Fig. 79.2). Autograft from the reaming is used to augment biology, filling any gaps between the iliac bone and the femoral head (20,24).

The surgical technique is considered successful if we manage to increase bone contact, to apply compression at the fusion area and to stabilize with rigid internal fixation.

The postoperative course consists of touchdown weight bearing from the first postoperative day. The use of a removable brace is warranted to protect our fixation, especially

for overactive, noncompliant patients, and for the cases that bone contact and fixation are considered suboptimal. Weight bearing is increased as tolerated at 6 weeks and after 3 to 4 months, patients are allowed to weight bear without supportive devices (19,22).

for overactive, noncompliant patients, and for the cases that bone contact and fixation are considered suboptimal. Weight bearing is increased as tolerated at 6 weeks and after 3 to 4 months, patients are allowed to weight bear without supportive devices (19,22).

Outcomes

Hip arthrodesis, not as favorable today by patients and surgeons, is still a good alternative to total hip arthroplasty for very young and active patients with unilateral joint disease. This procedure can provide long-term pain relief and functionality. Sponseller et al. (25) and Callaghan et al. (19) showed that the durability of arthrodesis is outstanding; patients may be still active 30 years postoperatively. However, patients’ satisfaction is fair, with 65% of them declaring uncertainty whether they would have undergone this procedure again (19,21,23,25).

Complications

Back and ipsilateral knee pain may occur in up to 60% of patients with hip arthrodesis. However, symptoms generally present not earlier than 20 years postoperatively, and they usually do not affect everyday life activities. A 26-mm average leg length discrepancy should be expected. The ipsilateral knee may develop ligamentous anteroposterior laxity. Contralateral hip pain is less common than back and knee pain.

Some patients complain of functional impairment affecting everyday life activities, such as shoe wear, prolonged sitting, and even problems with sexual activities (19,25).

Although, patient satisfaction is suboptimal, only a small number of patients with hip arthrodesis are seeking additional surgical intervention (i.e., conversion to a total hip arthroplasty). The main reason for conversion is debilitating back and/or ipsilateral knee pain (26). The patient should be aware of the potential risk of converting a functional stable hip into a nonfunctional unstable one. Therefore, the procedure should be carefully considered and indicated only when pain is truly disabling. Moreover, the procedure is technically demanding with regard to preservation of hip abductors, protection of sciatic nerve or surrounding vasculature (which may be incorporated into the fusion mass), and careful selection of the height of osteotomy trying to preserve as much acetabular bone coverage as possible (26).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree