Rowing

Patrick F. Leary

The sport of rowing dates back to the early Egyptians. They documented the sport circa 3300 B.C. Ancient Greek galleys had a total of 170 oars on three decks, 85 oars per side. The forefather of the modern-day coxswain/coach, the stroke master, was also the disciplinarian. Early on he must have observed the need for symmetrical corporal punishment, less the ship would endlessly circle.

Paddle sports include rafting, rowing, kayaking, and canoeing. Each presents with different injury patterns both on and off the water. Varied training cycles, diverse equipment, many participants, during different seasons, make for a sports medicine challenge. The scope of this discussion is limited to sweep rowing, sculling, and crew.

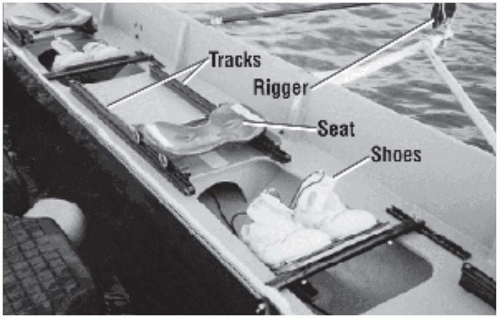

From ancient Athenian mariners to the Head of the Charles, rowing a boat has been an essential function for thousands of years. For work or play, for war or sport, the object has always been to arrive first. Club, college, amateur or professional, rowing popularity in the United States came with the urbanization of the cities. The Detroit Yacht Club was established in 1839, and was represented by singles, pairs, and sixes. The first intercollegiate sport in the United States was a row between Harvard and Yale in 1852. This race featured the classic eight shell, which is still used today, where the coxswain sits in the back of the boat (the stern), that is, the last portion of the boat to cross the finish line. The rowers sit on slides with their feet laced in the foot stretchers, facing the coxswain (Fig. 36.1), who acts as the on-board coach and maintains maneuverability. The rower closest to the cox is called the stroke, the quintessential rower with the best technique to be emulated by the rest of the crew.

In 1873 the Boating Almanac and Boat Club Directory boasted 289 boat clubs in 25 states (1). The clubs raced sixes without a cox, racing for 3 miles with a 180-degree turn in the middle. This created confusion and chaos and on occasion, disastrous results.

The Ivy League schools met in 1875 in front of 25,000 spectators at Saratoga, New York, for a 3-mile straight eight shell with a coxswain. Historically, the shells were shorter, wider, and heavier, as were the rowers themselves.

At the turn of the century, rowing challenged baseball as America’s favorite pastime. Regional communication was improving with urbanization. Industrialization was linked to water supplies.

Consequently, rowing popularity followed the plight of the big city. Gambling caught on from Maine to Milwaukee, and Boston to San Francisco. Thousands turned out for the popular regattas, which shared a festival quality and filled an entertainment void. For the rowers, a sense of health and character complemented a feeling of pure pleasure. Rowing catered to a growing number of participants and spectators with great affluence and free time.

Head races are usually held in the fall season; races are 4,000 to 6,000 meters (2.5 to 3.75 miles) with a running stagger start and they are usually held on local rivers and lakes. The official National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) sanctioned races in the spring are in eight shells with a cox for 2,000 meters (1.25 miles), or approximately 120 strokes. The shell is 60 ft long and weighs approximately 200 lb. The races last anywhere from 5 to 9 minutes.

Sculling by contrast is usually singles, pairs, and fours. Each rower has two smaller oars.

A single shell is 27 ft long, 10 in. wide, and weighs 23 lb (1).

A single shell is 27 ft long, 10 in. wide, and weighs 23 lb (1).

FIGURE 36.1. A typical rowing boat includes a rigger, seat, tracks, and shoes, which are fixed to the boat. (Courtesy of Physician and Sports Medicine, Vol 28, No. 4, 2000.) |

Summer Olympics rowing is second only in number of participants to track and field. Dr. Benjamin Spock, the famous pediatrician, rowed the eight shell to a gold medal in the summer of 1924. However, the expense of the equipment and the large number of rowers needed have limited the popularity of crew rowing. Available waters and weather conditions and hectic school schedules have limited the development of broad-based intercollegiate participation.

Women have participated in rowing for 90 years, but since the inception of the Title IX Amendment to the Equal Opportunity Act of 1972, rowing has afforded women great opportunities to participate in collegiate competition. Universities have been able to offer literally tens of thousands of young women a chance to participate in college athletics as a result of rowing alone. New technologies in equipment and training have contributed to the increased popularity of the sport. Unfortunately, technology has also sparked a whole new variety of sport-specific injuries.

Classifications can include juniors, who are under 18 years of age, and masters, who are older than 27 years of age. Flyweight classifications are for women under 100 lb and for men under 135 lb. Midweight women are under 135 lb and men under 165 lb. All others are included in the open or heavyweight classification. Other classifications emphasize experience without regard to weight. They include the novice-varsity designation.

Race distances vary in the fall depending on the venue. A dash is 500 meters long, while head races are 4,000 to 6,000 meters. The annual Head of the Charles race in Boston attracts 3,000 rowers, 700 crews, and 50,000 spectators crowding the banks of the Charles River.

Rowing is one of the oldest and most strenuous of all sports of the modern Olympics. A successful rower needs well-developed aerobic and anaerobic capacity, strength and stamina year round, and competitive anthropometric characteristics. These include height, arm span, girth, body mass, and skin fold measurements (2). Distribution of slow twitch and fast twitch muscle fibers in a canoeist demonstrated 71% slow fibers and 29% fast fibers (3). A tall athlete has the ideal physique for a sweep rower. Champion rowers tend to be taller and heavier than their counterparts (2). Greater height has been reported to enhance the sweep rower’s leverage; however, this feature may cause greater injury to the spine. Upper body strength is no more important than strong legs and a flexible lumbosacral spine. A 2,000-meter race combines a unique balance of early aerobic and later anaerobic exertion. Maximal oxygen uptake for 20- to 35-year-old rowers is 60 to 72 mL/kg/min for men and 58 to 65 mL/kg/min for women. Ranges of relative body fat for rowers are 6% to 14% for men and 8% to 16% for women (3).

PREHABILITATION

Sports medicine physicians must look for a broad scope of possible injuries in a rower. Rowing is an endurance sport which includes the fall head races, winter dry-land conditioning, spring NCAA competitions, and summer regattas. Injuries common to weightlifters, swimmers, cyclists, and distance runners are also seen in the rower.

Disc herniations in a sweep rower frequently have a different presentation in a sculler. The symmetrical motion of the sculler tends to extrude the disc centrally and posteriorly, avoiding the classic symptoms of sciatica. Coxswains need to be screened for signs of the the athletic triad (amenorrhea, osteoporosis, disordered eating) (6). The one-legged squat maneuver can eliminate concern over ankles, knees, hips, and sacroiliac joints along with some indication of hamstring-quadriceps strength and balance. The Watkins protocol can help screen for low back pain, inflexibility, and strength deficits. This protocol employs core stabilization maneuvers in a ramped sequence which screens for low back deficits.

COMMON INJURIES

Most rowing injuries can occur as a result of training or equipment incompatibility. Injuries are more likely to occur during practice than in the shell, and are more frequently a result of running, weightlifting, and erging than racing. Rarely, injuries are sustained as a result of weather conditions or even frank trauma.

Rowers develop injuries at various sites (Fig. 36.2). Hosea et al. reported on 180 rowers over a 3-year period. The two most common injuries were of the knee (29%) and the back (22%). Back pain ended careers in 16% (4). Back pain has been reportedly caused by sacroiliac dysfunction, spondylolysis, and disc herniation. Costovertebral joint strains are common with sweep rowers. Training injuries include rib stress fractures, and all other stress fractures associated with overuse including the sacrum (7). Medial tibia stress syndrome, patellofemoral syndrome, plantar fasciitis, forearm tendinitis, and sculler’s thumb have all been reported in rowers. Equipment injuries include callus formation of the hands, blisters, track bites, and ischial tuberosity bursitis or rower’s butt. Several different injuries have been reported by a fatigued crew awkwardly lifting a wet shell out of the water and carrying it into the wind. Rarely, traumatic injuries result from catching a crab, capsizing, or collisions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree