Rheumatoid Forefoot Reconstruction

Xan Courville

Florian Nickisch

Timothy C. Beals

Charles L. Saltzman

The natural history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has changed with newer disease-modifying pharmacologic agents. Many RA patients do not have as severe progression of disease as we had seen in the past. Furthermore, the results of surgery in patients with stable disease may not deteriorate over time, which has allowed the type of procedure to change to nonrheumatoid forefoot reconstructions from the typical Hoffman-type procedures (1,2).

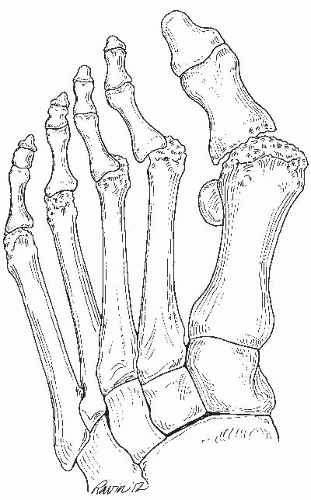

About 15% of rheumatoid patients have forefoot involvement that is painful and may need an operation (3). Virtually all patients with long-standing untreated disease have metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint involvement. Initially these joints are swollen and painful from both cellular and humoral misregulation of the immune system. Synovial proliferation or pannus invades and destroys periarticular bone and cartilage. The swelling permanently stretches surrounding ligaments. When this acute phase of synovitis resolves, the residual joint laxity leads to subluxation and dislocation. Although any possible deformity can occur, the most common problems are hallux valgus and lesser toe clawing (Fig. 13.1). Patients complain of pain under the central metatarsal heads, around the medial eminence of the first metatarsal, and on the dorsum of the toes.

Nonoperative management includes extra-depth shoes constructed from a soft pliable or temperature-moldable material, custom inserts with metatarsal pads, and a surface interface of mediumdensity Plastizote. A rocker bottom or metatarsal bar can be added to the sole of the shoe to unload the forefoot for severe metatarsalgia. Factors that influence surgical outcome include patient selection, surgical timing, and operative technique. Although there is an assortment of operations that have been applied for correction of the rheumatoid forefoot, the forefoot arthroplasty featuring first MTP arthrodesis, resection arthroplasty of the lesser MTP joints, and hammer toe correction with either osteoclasis or hemiphalangectomy is considered by many to be the standard and is described.

More recently, there has been interest in joint-sparing RA forefoot arthroplasty with distal oblique metatarsal osteotomies combined with either a first metatarsal osteotomy or a first MTP arthrodesis proposed in feet without severe destruction of the metatarsal heads. An osteotomy of each of the lesser metatarsal heads is made parallel to the plantar surface of the foot from distal to proximal. Upon completion of the osteotomy, the metatarsal heads will automatically shorten. A second thinning parallel cut is made to further offload the metatarsal head. The osteotomy site is fixed with one or two 2.4- or 2.0-mm screws.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Indications for surgical reconstruction of the rheumatoid forefoot include (a) pain and deformity unrelieved by nonoperative means and (b) impending or recurrent ulceration. Contraindications include severe soft tissue fragility, vascular insufficiency, and ongoing deep infection. Relative contraindications are cervical spine instability, gait unsteadiness, and long-standing steroid dependence.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A complete history and physical examination should be done on every RA patient prior to surgery.

A history of increasing unsteadiness or the physical finding of lower extremity hyperreflexia can indicate cervical myelopathy and deserve prompt attention.

Lateral flexion-extension radiographs of the cervical spine are routinely obtained (4). Magnetic resonance imaging is indicated when neurologic deficit (myelopathy) occurs, and when plain film radiographs show a posterior atlantodental interval less than or equal to 14 mm, any degree of atlantoaxial impaction, or subaxial stenosis with a canal diameter less than or equal to 14 mm (5). Patients with significant instability or myelopathy should be advised to consider cervical spine stabilization prior to foot surgery.

Whether it is necessary to discontinue antirheumatic or anti-inflammatory medications perioperatively to minimize infections or wound complications is under current debate. Three recent studies showed no difference in infections or wound problems in patients who stopped their medications compared to patients who continued their medications including methotrexate, corticosteroids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), hydroxychloroquine, gold, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha antagonists (6, 7 and 8). A large retrospective cohort study did show a trend toward increased infection rates with continuation of medications perioperatively, although not statistically significant (9). A theoretical risk for perioperative infection certainly exists for patients on these medications; however, clinically it has yet to be proven that immune-compromising medications are a risk factor for perioperative infections in foot and ankle surgery.

Patients with upper extremity arthritic involvement benefit from preoperative instruction in the use of Canadian crutches, a walker with wheels, or a wheeled leg-rest tricycle. The ease of postoperative recovery can be enormously facilitated by arranging home care or physical therapy in advance of surgery. The optimal timing of surgery for patients with bilateral problems is a matter of debate. Our preference is to stage procedures with a minimum of 6 months between operations. With this approach, the patient has the nonoperated foot on which to bear weight after surgery and, as a result, has less postoperative morbidity. Moreover, the patient is able to judge the true benefits of surgery before having both feet reconstructed. In rare circumstances (e.g., patients with bilateral plantar ulcerations or with severe anesthetic risks), it may be wiser to treat both feet simultaneously.

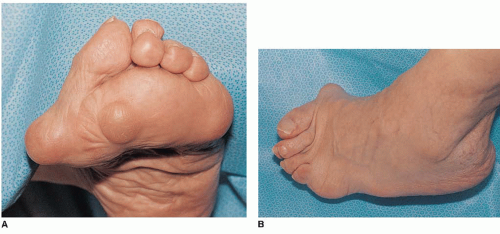

In addition to the general history and physical examination, a focused evaluation of the foot (Fig. 13.2) is necessary to document the condition of the peripheral vasculature, the severity and location of skin calluses or vasculitic lesions, including inspection of nails for hemorrhages, the

location of deformities, and the patient’s locus of pain. The radiographs include a weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP) foot, a weight-bearing lateral foot, and a non-weight-bearing oblique foot view. From these radiographs, the degree of osteoporosis, joint deformity, including subluxation or dislocation, as well as the amount of rheumatoid joint destruction is visualized.

location of deformities, and the patient’s locus of pain. The radiographs include a weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP) foot, a weight-bearing lateral foot, and a non-weight-bearing oblique foot view. From these radiographs, the degree of osteoporosis, joint deformity, including subluxation or dislocation, as well as the amount of rheumatoid joint destruction is visualized.

No single operative approach suffices for all patients. The great toe can drift into valgus or varus at the MTP joint, have interphalangeal (IP) arthritis or dislocation, develop clawing from intrinsic imbalance or tendon attrition, and be endowed with either soft or hard bone stock. Although arthrodesis of the first MTP joint is generally preferred (10,11), a resection arthroplasty may be a better procedure for a patient with insufficient bone stock, extrinsic tendon rupture, or significant IP symptoms. More recently, with anti-TNF-alpha medications in widespread usage, traditional hallux valgus surgeries such as Chevron and Scarf osteotomies and Lapidus fusions with distal soft tissue procedures have also been used in RA patients on rheumatoid medications with preservation of joint congruency (1,2).

Similarly, treatment of the lesser toes should be individualized. Variable degrees of deformity can develop, ranging from mild MTP subluxation to fixed MTP dislocation with rigid clawing. The traditional surgical approach to these problems is MTP resection arthroplasty (12). The approach and extent of resection, however, may be modified to accommodate each patient’s particular problems. Mild deformities are treated with minimal resections, whereas severe deformities require more bone removal. In borderline clinical decisions, we tend to remove more rather than less bone since attaining soft tissue relaxation through an adequate bony excision is fundamental to the procedure’s success (12).

Synovectomy alone has been shown to be temporizing only (13). With increased use of rheumatoid disease-modifying agents, there have been proponents for joint-preserving surgery for forefoot deformities with the use of distal or proximal osteotomies of the lesser toes. Weil metatarsal osteotomies of the lesser metatarsals are one option for preserving the MTP joints (1). Other authors have proposed proximal metatarsal shaft osteotomies (2). Joint-preserving surgery is contraindicated when there is severe destruction of the metatarsal heads.

We have not routinely found it necessary to do open hammer toe repair (proximal phalangeal condylectomy), but this is described in the literature (10). Coughlin reported better results with proximal interphalangeal (PIP) arthrodeses than with partial resection (10). We reserve this procedure for patients with severe, fixed deformities, as closed osteoclasis in these cases can result in plantar skin lacerations.

There are a variety of methods to address the hammer toe deformity that occurs in the rheumatoid forefoot. We prefer closed osteoclasis for mild to moderate fixed deformities. We do this with direct extension manipulation and find that our deformity correction is usually adequate. Toe alignment is maintained with a 0.062-inch Kirschner wire (K-wire) across the distal interphalangeal (DIP) and PIP joints for 4 weeks. In cases of combined hammer toe correction and metatarsal head resection, the K-wire is advanced into the remaining metatarsal and left in place for up to 6 weeks.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The patient is positioned supine with the operative table inclined in mild, reverse Trendelenburg. The foot is positioned with the heel within inches of the end of the table. This enables the surgeon to have full access to the forefoot from the end of the table and facilitates fluoroscopic examination with a mini c-arm. Preoperative antibiotics are given within 60 minutes of surgical start time.

A 12- or 18-inch inflatable tourniquet is wrapped about the midcalf. If joint-preserving surgery is performed, we prefer the use of a thigh tourniquet, as ankle tourniquets bind down the flexor and extensor tendons to the toes and make adequate soft tissue balancing difficult.

The foot is sterilely prepped. For patients with marginal skin, the foot is exsanguinated by gravity; for all others, a 3-inch Esmarch bandage is used. The tourniquet pressure is set at 100 mm Hg greater than the systolic pressure. Complete reconstruction of the rheumatoid forefoot can be time-consuming. After 2 hours, the tourniquet pressure is released to reduce the potential for neurovascular complications.

Meticulous, atraumatic soft tissue handling is essential when performing rheumatoid forefoot surgery. This can be accomplished with single- and double-pronged skin hooks, Boyes-Goodfellow retractors, and Adson forceps. Self-retaining retractors are to be used only sparingly as they can crush the fragile capillary networks of the rheumatoid forefoot.

Exposure

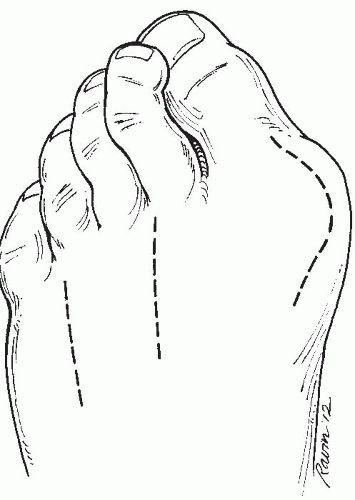

These are performed in RA patients with severe destruction of the metatarsal heads. We prefer to use two longitudinal dorsal incisions for the lesser resections and a third dorsomedial incision for the first MTP fusion. When doing a first MTP fusion, the lesser toe procedures are completed first to protect the arthrodesis construct. Many different incisions have been advocated. These vary from transverse to longitudinal approaches, across plantar or dorsal surfaces, with or without soft tissue excision.

The initial incisions are placed in the second and fourth webspaces, approximately 3 cm in length (Fig. 13.3).

Thick flaps are developed by sharp dissection directly down to bone with the neurovascular bundle remaining in the plantar flap. The second and third MTP joints are exposed through this incision.

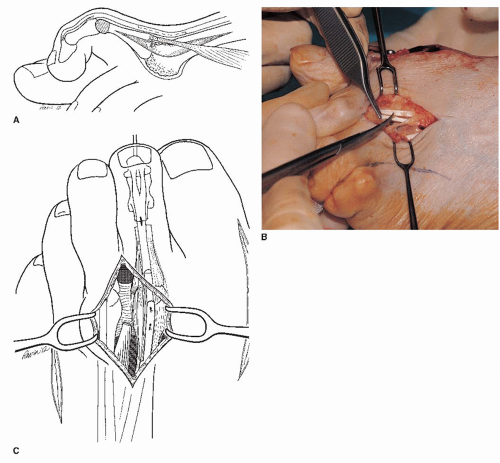

The short extensor is transected. A Z-shaped cut is made in the long extensor of each toe. These ends are repaired in a Z-lengthening repair following the metatarsal head resection (Fig. 13.4A and B).

Lesser Metatarsophalangeal Arthroplasties

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree