Revision Lumbar Surgery

Todd B. Francis

Gordon R. Bell

DEFINITION

There are a multitude of different reasons why a patient may need to undergo revision lumbar surgery. Of all patients who have an operation for degenerative lumbar disease, approximately 15% will require a revision surgery.6

The term failed back syndrome (FBS) has been used to describe patients that experience poor clinical outcomes following lumbar surgery for degenerative causes, usually involving the intervertebral disc.8

Although this is a significant diagnosis in patients requiring lumbar revision surgery, it is not all inclusive in that it typically does not include patients with trauma, tumor, infection, or nondegenerative deformity who require reoperation.

ANATOMY

It is mandatory to obtain weight-bearing preoperative films to visualize the anatomy and to aid in localization. This is especially true when identifying hardware and intact bony elements as landmarks for the correct level to be operated on.

When reoperating on patients having had previous back surgery, spinal anatomy can be considerably distorted. In most cases, the normal bony landmarks and natural anatomic planes are often not present and may be replaced with dense fibrous scar. The dura underlying the scar can be densely adherent to it, and the surgeon can easily cause an unintended durotomy if dissection is not carried out with caution.

In general, the key to exposing a previously operated spine is to identify the normal anatomy and to ultimately identify the lateral wall of the bony canal which is a key landmark in identifying the neural elements. Residual bone lateral to the spinal canal (eg, the facet joints or bony fusion mass) and implanted instrumentation can also serve as valuable and reliable landmarks.

When reoperating on the lumbar spine, especially if hardware is in place, dissection is best started laterally by identifying the facets or hardware. From here, the surgeon can work medially to remove scar and identify dura, if necessary.

In patients without implanted hardware, it is safest to extend the original incision, exposing normal anatomy above and below the previous operative site. This makes it easier to identify the correct level, and dissection can proceed toward the area where the anatomy is uncertain.

PATHOGENESIS

The risk of developing a recurrent lumbar disc herniation after discectomy is approximately 5% to 18%.1,2

Some common causes for persistent or recurrent symptoms after lumbar surgery include failure to identify or address all of the pathology (eg, lateral recess stenosis, foraminal stenosis, or disc herniation), postoperative instability (eg, spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, kyphosis, and flat back deformity), adjacent level disease, and scar formation.3

Some element of scarring occurs after all surgeries. The presence of peridural fibrosis following decompressive spinal surgery does not necessarily implicate it as a cause of the patient’s symptoms, therefore. However, patients undergoing lumbar revision surgery tend to have poor outcomes when significant fibrosis is present.4

Pseudarthrosis in the setting of spinal fusion surgery refers to the radiologic failure of new bone to form across the intended joint space.

The underlying reason why a patient may require lumbar revision surgery can be suggested by evaluating the duration of symptom relief following the initial surgery.

If the patient had no symptom relief following surgery, either the surgeon did not address the genesis of the pain or an inadequate surgical procedure was performed.

Transient relief of symptoms (<6 months) suggests the development of scar tissue as a cause of recurrence of symptoms.

If the patient experienced a long duration of relief of his or her symptoms (typically longer than 6 to 12 months), this suggests development of new pathology at either the same level or at a new level.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of recurrent pathology following initial surgery is not completely known but is likely similar to that of the original condition. In other words, the natural history of a recurrent disc herniation, for example, is likely similar to that of the original herniation: spontaneous resolution of symptoms in many cases.

Therefore, conservative treatment should be tried before surgical intervention.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

It is important to determine that the patient has been correctly diagnosed and treated.

The three broad questions that need to be determined and asked, based on the history and physical examination, are as follows:

Was the original diagnosis correct?

Was the choice of type of surgery appropriate?

Was the actual surgical technique appropriate?

When evaluating a patient with persistent symptoms after lumbar surgery, it is important to carefully review his or her medical and surgical history.

It is useful to categorize the patient’s chief complaint into one of three groups: leg pain predominant, back pain

predominant, or leg and back pain equal. This will aid the physician in determining the potential source of the patient’s continuing symptoms and guide his or her medical decision making appropriately.

Predominant leg pain, for example, suggests a neurogenic cause for the pain.

Predominant back pain, on the other hand, is likely not due to a neurogenic cause and the genesis of which is much more difficult to identify.

A detailed history of present illness and past medical history should be obtained.

In particular, it is important to establish a surgical timeline. The onset and characteristics of initial symptoms, a detailed description of all spinal surgical interventions, and the presence or absence of symptom-free periods should be documented.

All medications, especially narcotic analgesics and anticoagulants, must be recorded.

It is important to review the patient’s original presenting symptoms and compare these to the surgical procedure performed to ensure that the correct procedure was chosen.

In this regard, it is extremely helpful to review preoperative clinical notes and operative reports. These should be obtained whenever possible. The operative note should be scrutinized for comments about potential intraoperative adverse events such as durotomy.

The presence of additional factors that could affect outcome or recurrence of symptoms should be investigated.

These include the presence of a work-related injury, particularly if associated with a pending compensation claim.

The likelihood of secondary gain is a potentially significant factor in these patients.

The surgeon must also be cognizant of psychosocial issues before planning a revision operation. This includes depression and narcotic addiction.

The presence of these psychosocial factors (worker’s compensation, depression, anxiety, litigation, etc.) can have a significant negative impact on patient outcome after lumbar surgery.9

When in doubt about potential significance of such psychosocial factors, a psychological evaluation should be obtained.

The quality and pattern of the patient’s pain can provide significant information about the nature of the pain.

Leg pain that is described as burning, for example, suggests neuropathic pain, which is generally unresponsive to further surgical intervention.

Similarly, leg pain that is present constantly and is unchanged by activity generally suggests the presence of underlying changes in the nerve that are unlikely to be significantly changed by additional surgery. Such nonmechanical pain is not typical of neurogenic pain that is amenable to surgery, which is generally mechanical in nature.

In patients with leg pain, careful examination of the lower extremity joints and pulses is important to rule out nonspinal causes of this pain. This is particularly important in older patients in whom spinal disease frequently coexists with other degenerative conditions such as peripheral vascular disease and joint arthritis.

The presence of Waddell signs should also be documented, if present. One of the more significant Waddell signs is overreaction to pain. Other signs include superficial skin tenderness, regional disturbances, distraction phenomena, and simulation.

The presence of three or more Waddell signs indicates that the patient’s pain is likely nonorganic and portends a poor prognosis, particularly with further surgery.10

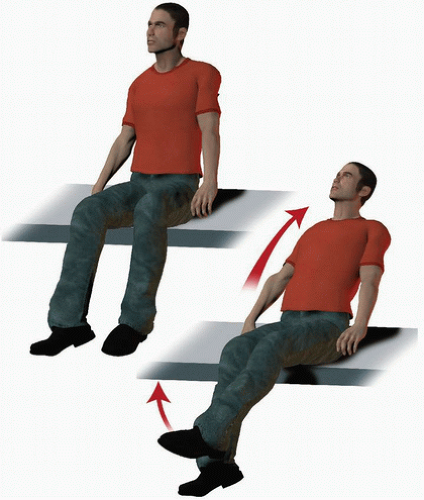

Distraction testing includes the “flip test” in which a patient demonstrates a positive straight-leg raise test in the supine position but not in the seated position (FIG 1). A straight-leg raise test in a patient who is exhibiting pain behavior will be easily achieved to 90 degrees, whereas a patient with pain from a true radiculopathy will “flip” back on their hands when attempting a sitting straight-leg raise in order to relieve tension in the sciatic nerve.7

With simulation, anticipatory behavior can be elicited through simulated movement. For example, the patient will report back pain through maneuvers that do not typically move the back such as mild trunk rotation through hip rotation (Table 1).

IMAGING STUDIES

Ideally, all of the patient’s preoperative and immediate postoperative films should be reviewed. This ensures that surgically correctable pathology was initially present and that it was addressed surgically, both in terms of operating at the correct level and by doing an adequate decompression.

All patients being evaluated for revision lumbar surgery should have a current standing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral plain x-ray of their lumbar spine.

This should also include a coned-down spot lateral view of the lumbosacral level, especially in patients with prior

surgery at L5-S1. This provides valuable information about sagittal and coronal alignment, hardware position and integrity, and bony anatomy.

If iatrogenic injury to the pars interarticularis is suspected, oblique views of the lumbar spine can be useful.

Flexion-extension lateral views of the lumbar spine can be useful to evaluate for segmental instability.

Most patients who have persistent back pain or leg pain after lumbar surgery will have a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of their lumbar spine.

In patients with a suspected recurrence of a disc herniation, it is important to make the distinction between recurrence and scar because the former is potentially amenable to surgery, whereas the latter is generally not. A precontrast and postcontrast (gadolinium) MRI is helpful to distinguish scar from recurrent disc herniation. Disc material is avascular and therefore will not enhance after gadolinium administration. Scar, on the other hand, is vascular and will therefore enhance with gadolinium.

In patients with older stainless steel implants, MRI is generally not useful because of significant metal artifact that obscures detail. Under such circumstances, a combined myelogram/computed tomography (CT) scan study is useful.

Distortion with titanium implants is less of an issue, but in some cases, distortion from titanium implants can occur, requiring a myelogram/CT scan to identify neural compression.

Patients who have an implantable pacemaker or internal defibrillator or who are claustrophobic are not candidates for MRI and should have a myelogram/CT scan to visualize compressive pathology.

CT without myelography using coronal and sagittal reconstructions is useful to evaluate hardware placement (especially pedicle screws) and to evaluate an interbody fusion for evidence of pseudarthrosis.

Three-foot long AP and lateral scoliosis x-rays are sometimes useful and are mandatory to evaluate overall spinal alignment.

Table 1 Vascular versus Neurogenic Claudication | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree