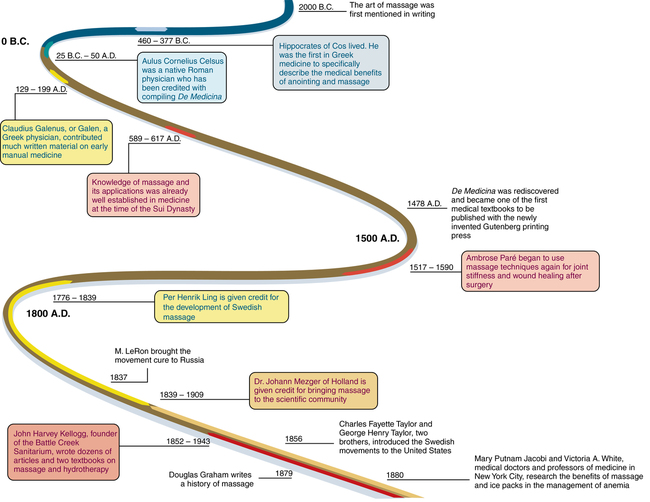

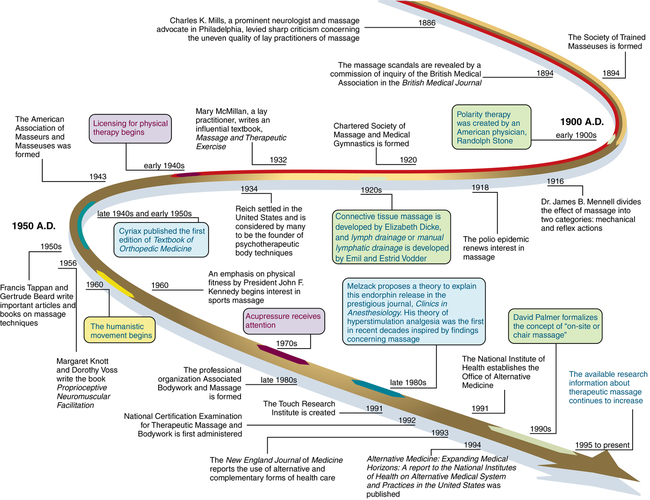

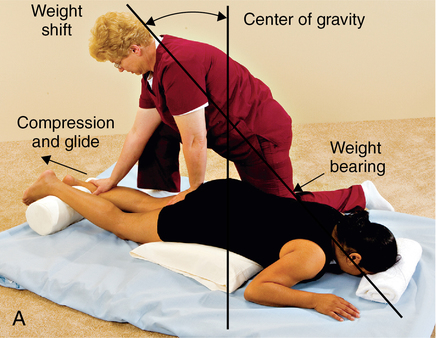

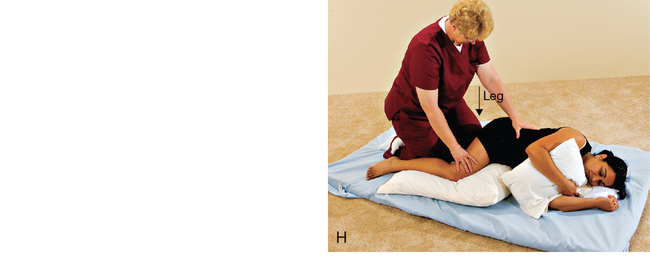

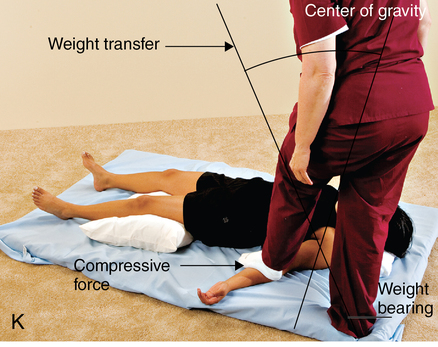

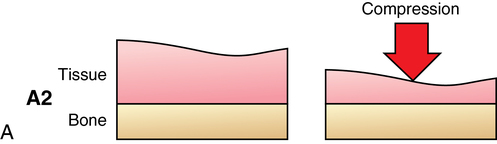

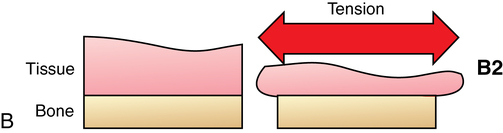

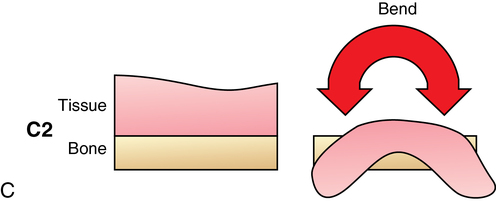

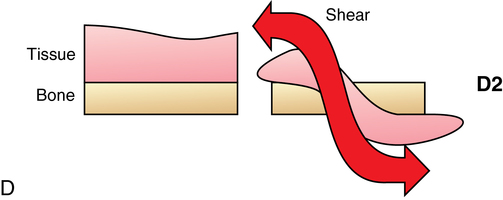

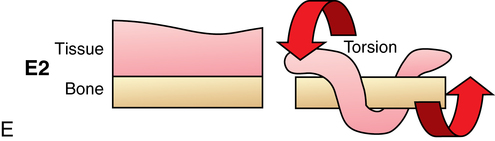

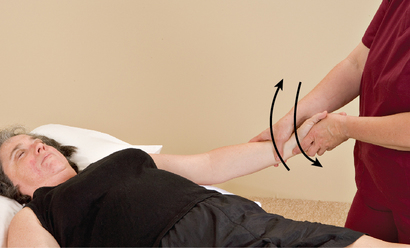

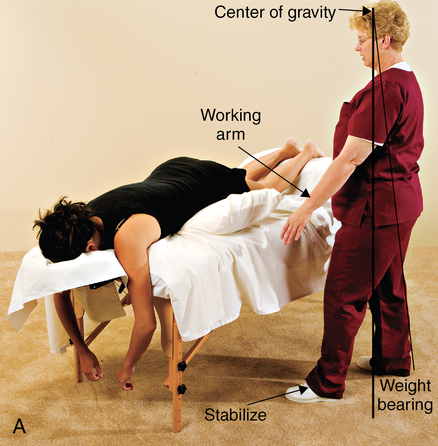

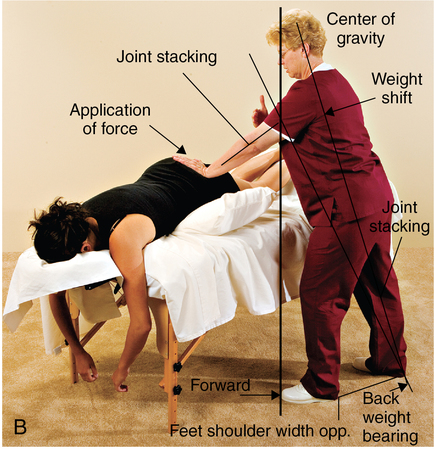

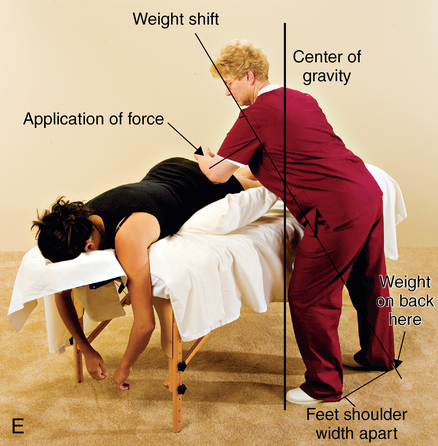

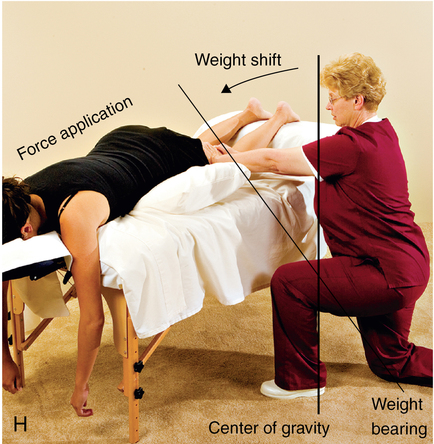

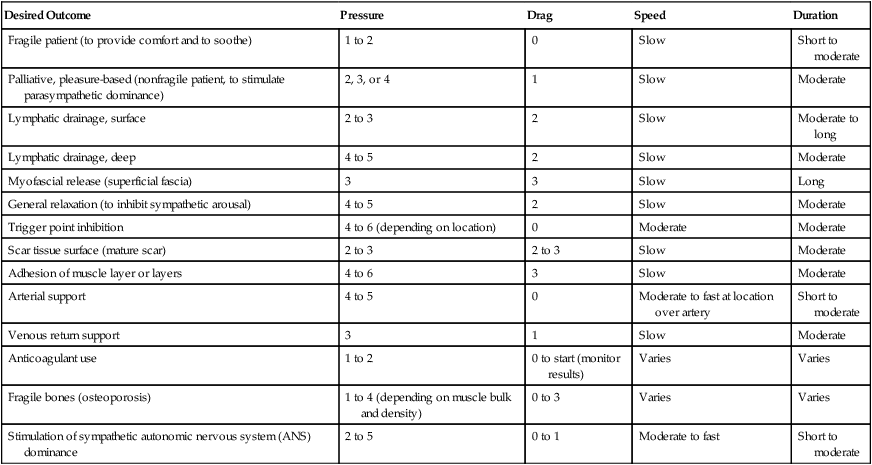

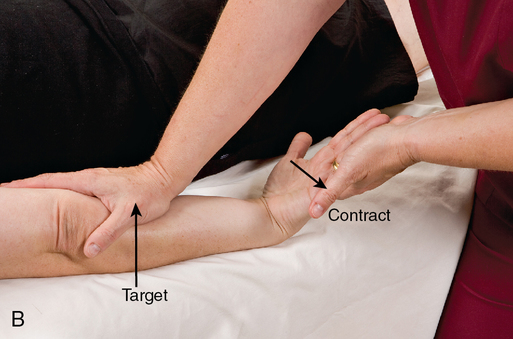

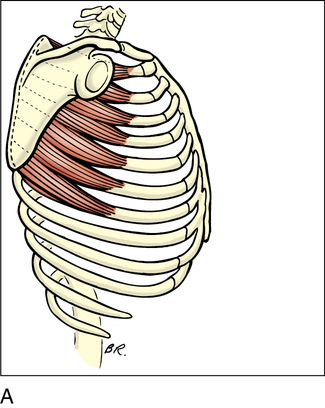

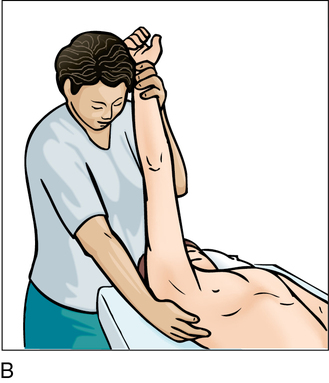

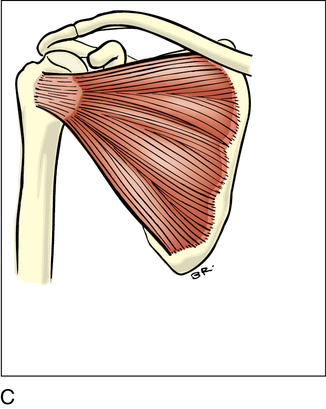

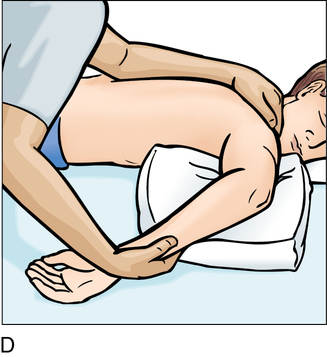

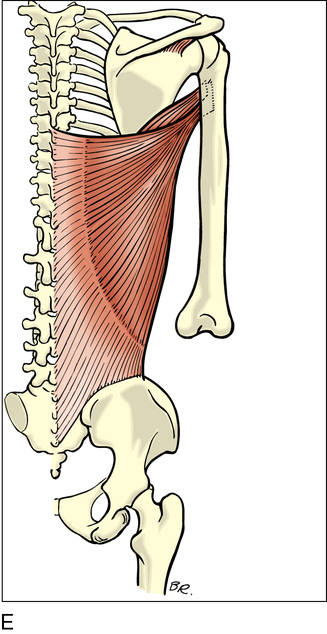

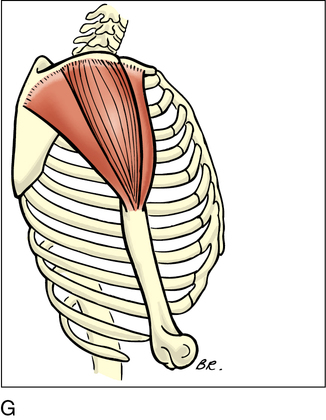

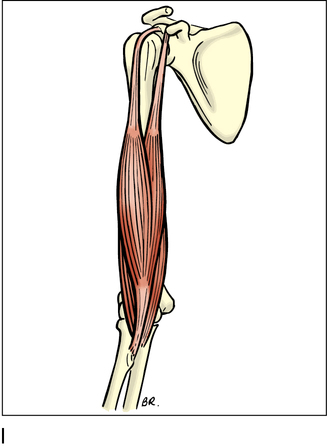

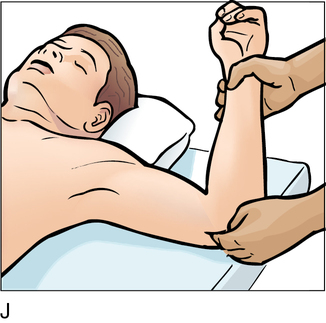

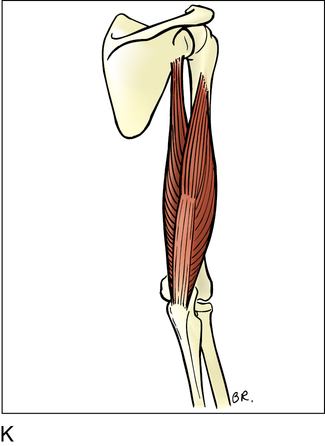

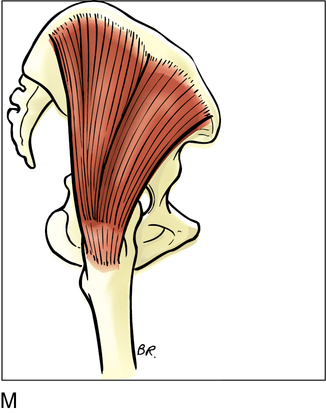

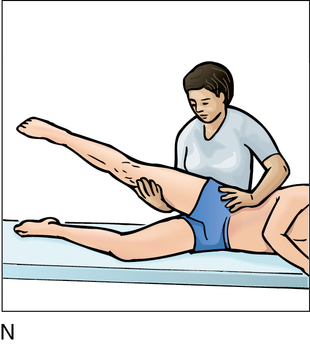

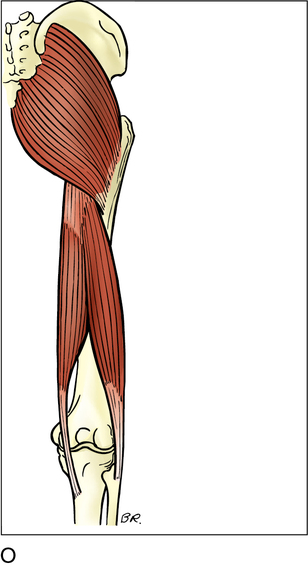

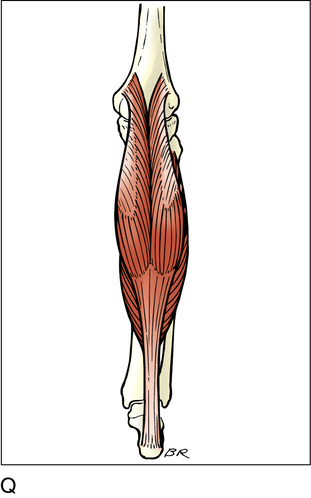

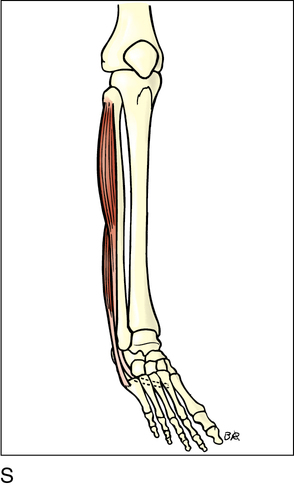

The history of massage provides an understanding of the present and guidance for the future. The time line in Figure 3-1 presents the historical highlights. A straight back and a pressure-bearing leg are other essential components of body mechanics. If the back is not straight, the practitioner often ends up pushing with the upper body instead of using the more effortless feeling of transferred weight. The practitioner’s weight should be held on the back leg and on the heel of the foot. At first, this may feel uncomfortable; however, some of the biggest and strongest muscles in the body are those in the legs. If you carry the weight on the back, fatigue sets in more quickly, and eventually, the pain can become debilitating. The core muscles and associated connective tissues of the posterior, lateral, and anterior torso are considered the core. The core includes large connective tissue structures such as the lumbar dorsal fascial and the abdominal fascia. The core muscles contract, pulling the connective tissues taut, and make a girdle-like structure to maintain upright posture. Massage therapists need core stability to maintain a straight back, stack joints, and shift the body’s center of gravity forward to apply pressure (Figures 3-2 and 3-3). Beginning with compressive force, we consider that increasing force is necessary to influence various layers of soft tissue from surface to deep, as well as physiologic factors (Figure 3-4 and Table 3-1). TABLE 3-1 General Guidelines for Pressure, Drag, Speed, and Duration in Massage Applications for Various Conditions When the massage begins, it is very important for this initial contact to be made with respect and a client-centered focus, as well as with the intention to meet client goals. With the holding/resting position, we enter the client’s personal boundary space. When application of the holding position has been mastered, it is easy to flow into the other methods, and gliding is often next in sequence (Figure 3-9). Gliding strokes are historically known as effleurage, which originates from the French verb meaning “to skim” and “to touch lightly on.” The most superficial applications of this stroke do this, but the full spectrum is determined by pressure, drag, speed, direction, and rhythm, making this manipulation one of the most versatile. The forces most commonly introduced by gliding are tension force, bending force, and compression force. The distinguishing characteristic of gliding strokes is that they are applied horizontally in relation to the tissue fibers, generating a tensile force. Gliding strokes also can be applied across fibers to create a bending force. During a gliding stroke, light pressure remains on the skin, and moderate pressure extends through the subcutaneous layer of the skin to reach muscle tissue, but not so deep as to compress the tissue against the underlying bony structure (Figure 3-10). Because the skin and the underlying muscles cannot be lifted (kneaded) without first pressing into them, compression (with the gliding stroke) should be done before kneading begins. Pétrissage, the historical term for kneading, is derived from the French verb petrir, meaning “to knead.” The soft tissue is lifted, rolled, and squeezed during application. Just as gliding focuses horizontally on the body, kneading focuses vertically and twists. The main purpose of this manipulation is to lift tissue, while applying bend, shear, and torsion forces (Figure 3-11). A variation of the lifting manipulation is skin rolling. Whereas deep kneading attempts to lift the muscular component away from the bone, skin rolling lifts only the skin and superficial fascia from the underlying muscle layer. Skin rolling is one of the very few massage methods that is safe to use directly over the spine. Because only the skin and superficial fascia are accessed and the direction of pull to the tissue is up and away from the underlying bones, the spine risks no injury, unlike when any type of downward pressure is used (Figure 3-12). Compression moves down into the tissue at a 90-degree angle. It can be a specific method that uses a lift and compress approach. Compressive force is an aspect of gliding and kneading, and compression proceeds downward into the tissues; the depth is determined by what is to be accomplished, where compression is to be applied, and how broad or specific the contact with the client’s body is (Figure 3-13). Shaking is a massage method that is effective in relaxing muscle groups or an entire limb. Shaking manipulations confuse the positional proprioceptors because the sensory input is too disorganized for the integrating systems of the brain to interpret; muscle relaxation is the natural response in such situations (Figures 3-15 and 3-16). Rocking is a soothing, rhythmic method that is used for calming. Rocking is both reflexive and chemical in its effects. For rocking to be most effective, the client’s body must move so that the fluid in the semicircular canals of the inner ear is affected, thereby initiating parasympathetic mechanisms (Figure 3-17). Hacking. This method is applied with both wrists relaxed and the fingers spread, with only the little finger or the ulnar side of the hand striking the surface. The other fingers hit each other with a springy touch. Point hacking can be done by using the fingertips in the same way. Tapping. The fingertips are used to apply targeted gentle stimulation. Cupping. Fingers and thumbs are placed as if making a cup. The hands are turned over, and the same action used in hacking is performed. When performed on the anterior and posterior thorax, cupping is good for stimulating the respiratory system and for loosening mucus. Slapping (splatting). The whole palm of a flattened hand makes contact with the body. This is a good method for releasing histamine to increase vasodilation and its effects on the skin. Beating and pounding. These moves are performed by using a soft fist with knuckles down, or vertically with the ulnar side of the palm (Figure 3-18). Friction manipulations are brisk concentrated strokes the generate heat and are thought to prevent and break up local adhesions in connective tissue, especially over tendons, ligaments, and scars, by creating therapeutic inflammation . The direction and depth can vary. One method of friction consists of small, deep movements performed on a local area. It provides shear force to the tissue. (Figure 3-19). Joint movements are methods that move each joint through various positions within the normal range of motion (ROM). These movements, which are never forced, can be active (AROM), when only the client moves; active assisted (AAROM), when the massage therapist helps the client move; active resisted (ARROM), when the massage therapist resists movement of the client; and passive (PROM), when the massage therapist provides movement (Figures 3-20 and 3-21). Contract and relax and antagonist-contract can be combined to enhance lengthening effects. This method can be called contract-relax-antagonist-contract (CRAC) (Figures 3-22 and 3-23). Stretching is a mechanical method of introducing various forces into connective tissue to elongate areas of connective tissue shortening. Muscle energy techniques are used to prepare muscles to stretch by activating lengthening responses. Longitudinal stretching pulls connective tissue in the direction of the fiber configuration. Cross-directional stretching pulls the connective tissue against the fiber direction. Both accomplish the same thing, but longitudinal stretching is done in conjunction with movement at the joint. If longitudinal stretching is not advisable, if it is ineffective in situations of hypermobility of a joint, or if the area to be stretched is not effectively stretched longitudinally, cross-directional stretching is a better choice. Cross-directional stretching focuses on the tissue itself and does not depend on joint movement (Figures 3-24 and 3-25).

Review of massage application

Body mechanics

Desired Outcome

Pressure

Drag

Speed

Duration

Fragile patient (to provide comfort and to soothe)

1 to 2

0

Slow

Short to moderate

Palliative, pleasure-based (nonfragile patient, to stimulate parasympathetic dominance)

2, 3, or 4

1

Slow

Moderate

Lymphatic drainage, surface

2 to 3

2

Slow

Moderate to long

Lymphatic drainage, deep

4 to 5

2

Slow

Moderate

Myofascial release (superficial fascia)

3

3

Slow

Long

General relaxation (to inhibit sympathetic arousal)

4 to 5

2

Slow

Moderate

Trigger point inhibition

4 to 6 (depending on location)

0

Moderate

Moderate

Scar tissue surface (mature scar)

2 to 3

2 to 3

Slow

Moderate

Adhesion of muscle layer or layers

4 to 6

3

Slow

Moderate

Arterial support

4 to 5

0

Moderate to fast at location over artery

Short to moderate

Venous return support

3

1

Slow

Moderate

Anticoagulant use

1 to 2

0 to start (monitor results)

Varies

Varies

Fragile bones (osteoporosis)

1 to 4 (depending on muscle bulk and density)

0 to 3

Varies

Varies

Stimulation of sympathetic autonomic nervous system (ANS) dominance

2 to 5

0 to 1

Moderate to fast

Short to moderate

Massage equipment

Massage table

Massage methodology

Holding/resting position

Gliding strokes

Kneading

Skin rolling

Compression

Shaking

Rocking

Percussion or tapotement

Friction

Joint movement/range of motion

Muscle energy methods

Combined methods: Contract-relax-antagonist-contract

Stretching

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Review of massage application

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue