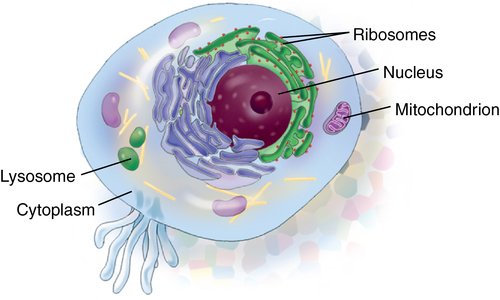

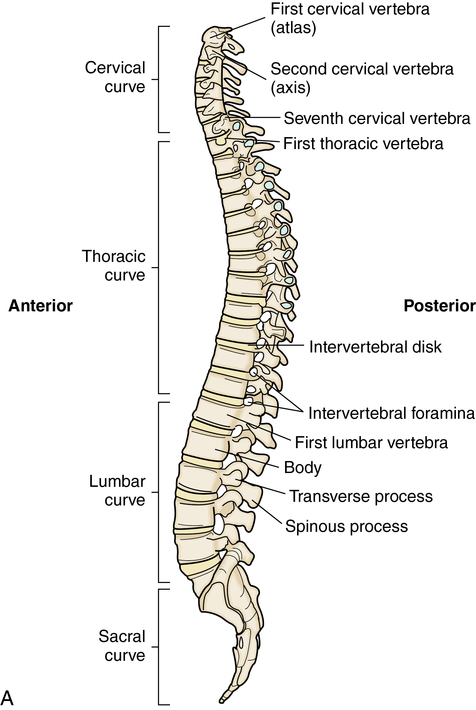

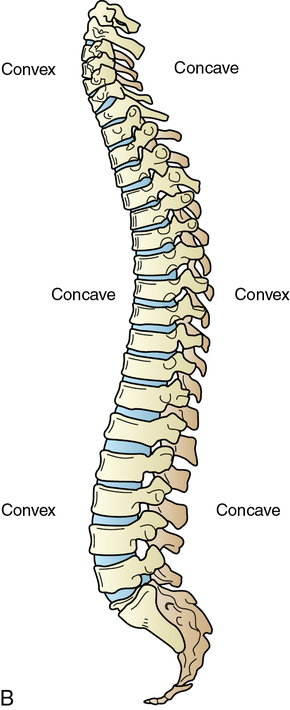

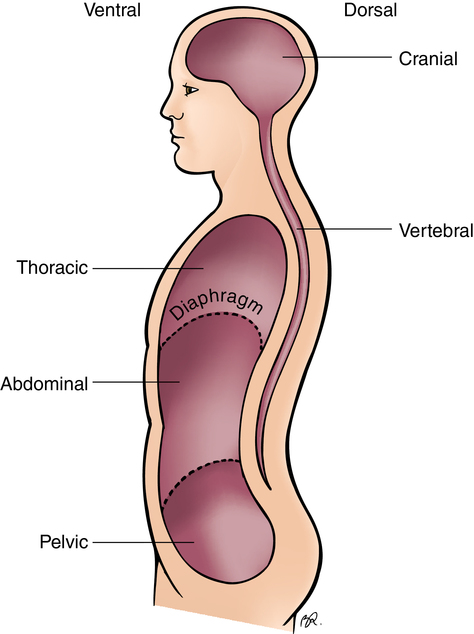

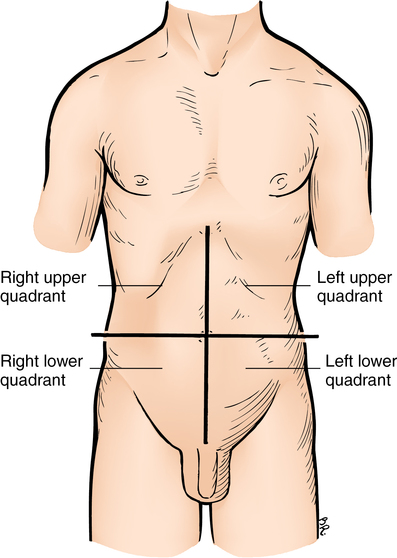

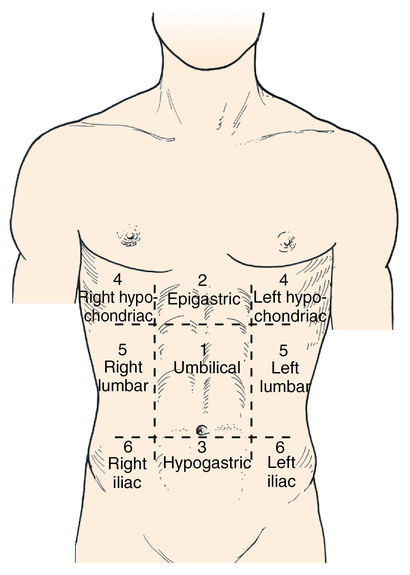

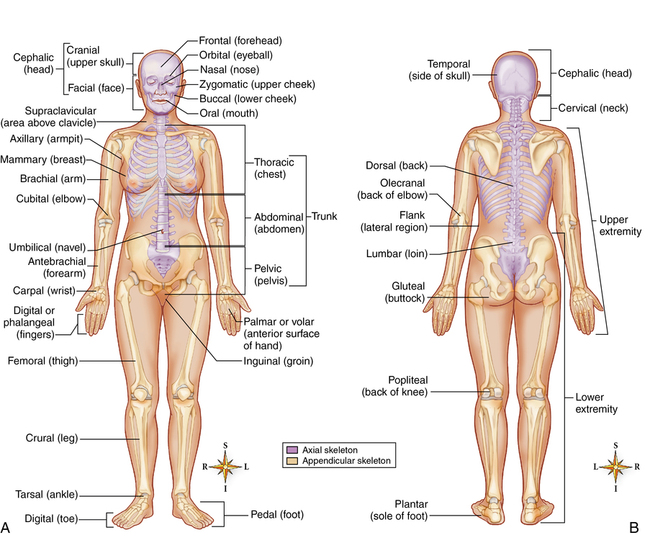

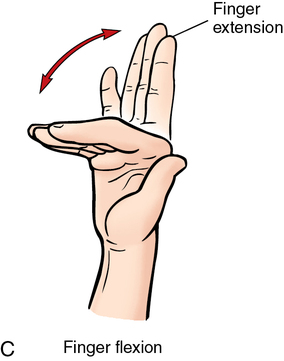

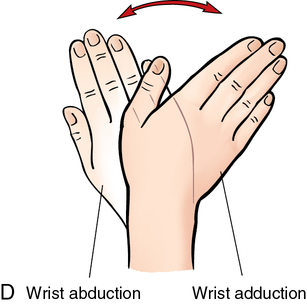

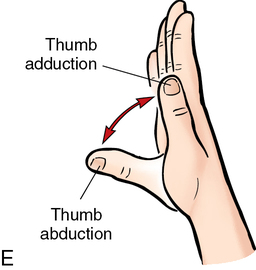

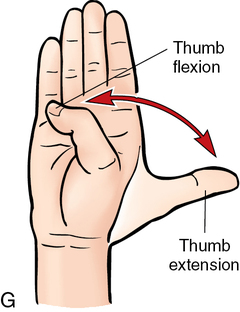

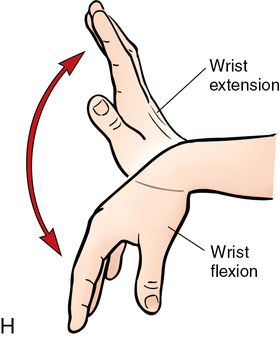

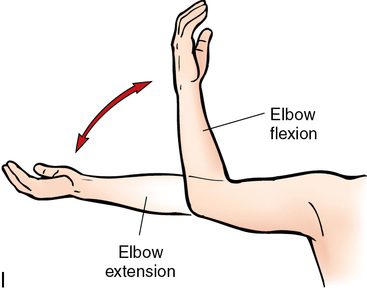

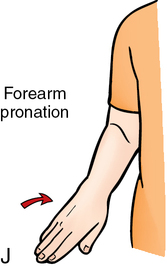

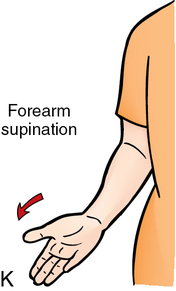

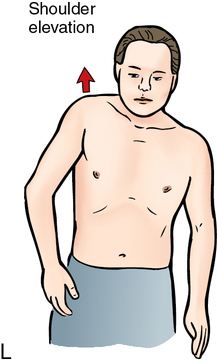

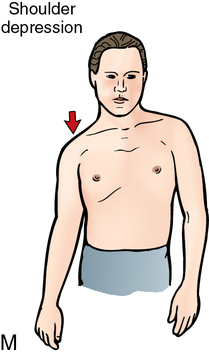

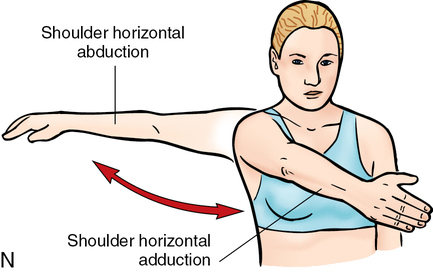

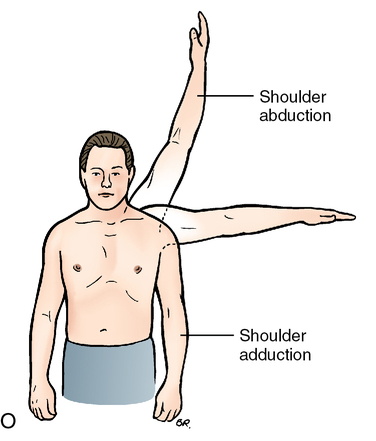

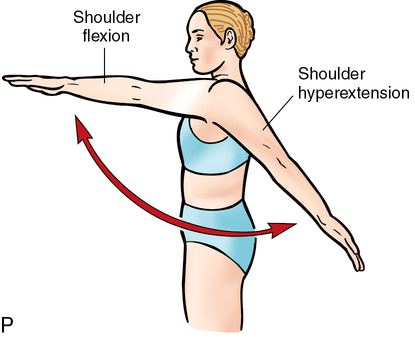

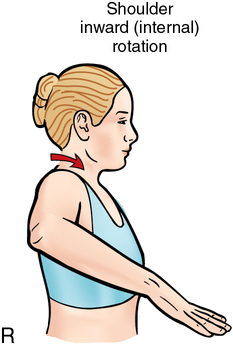

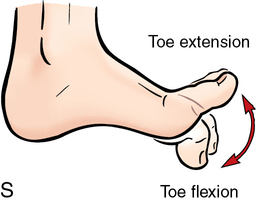

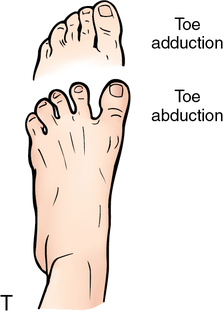

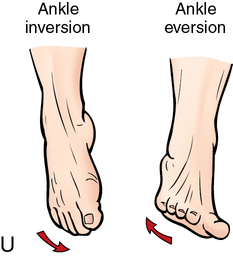

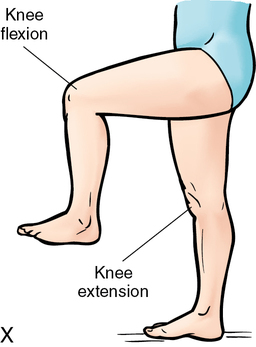

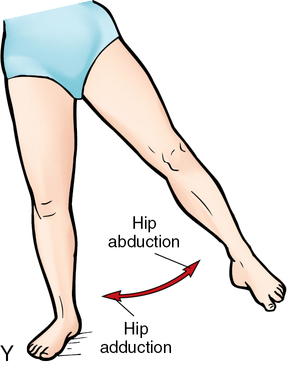

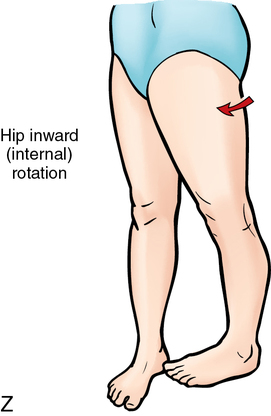

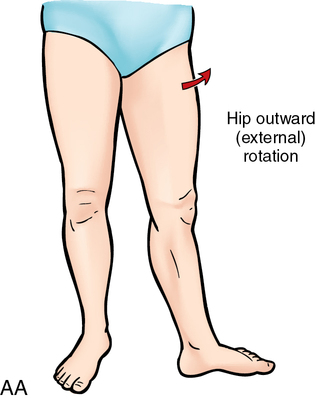

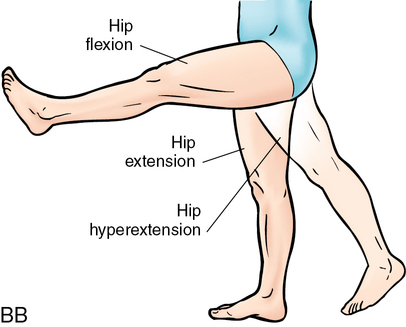

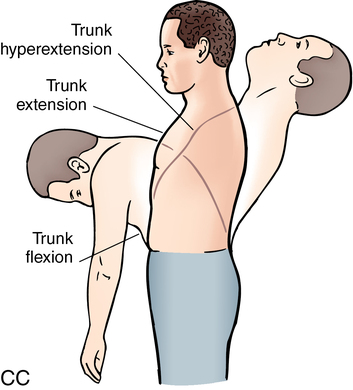

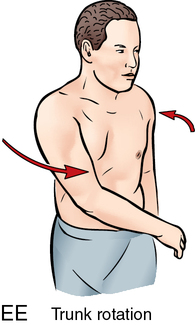

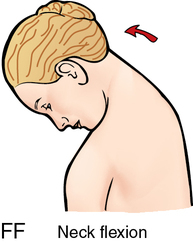

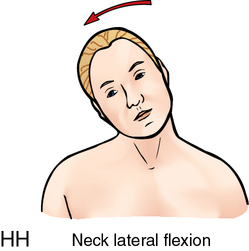

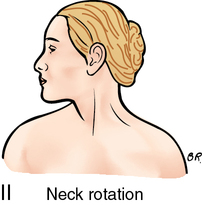

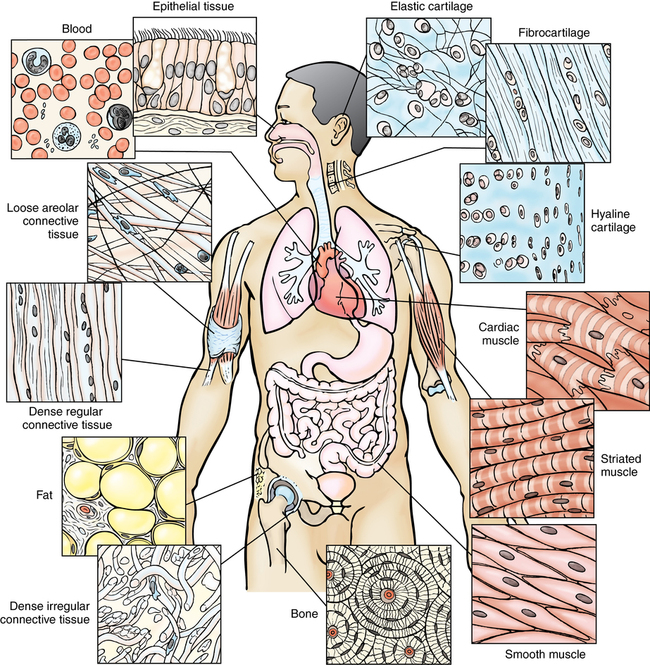

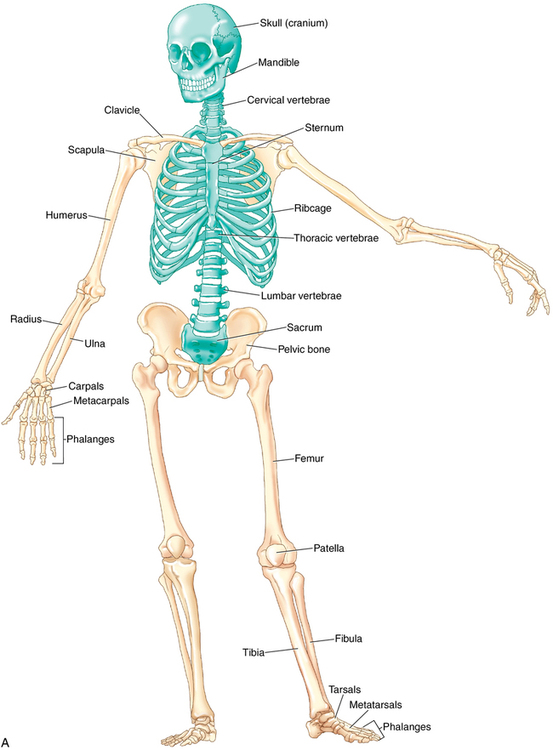

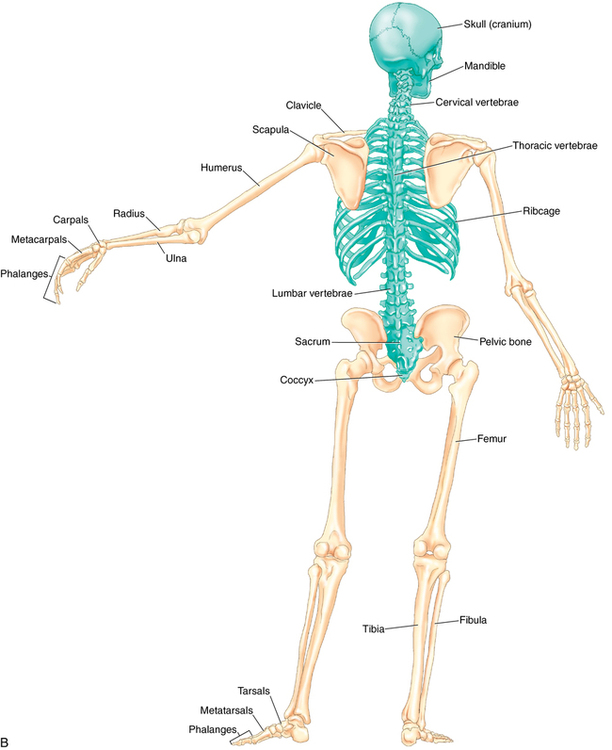

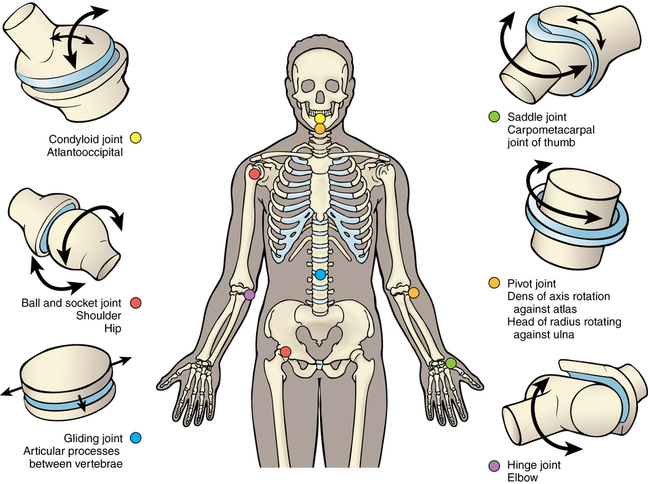

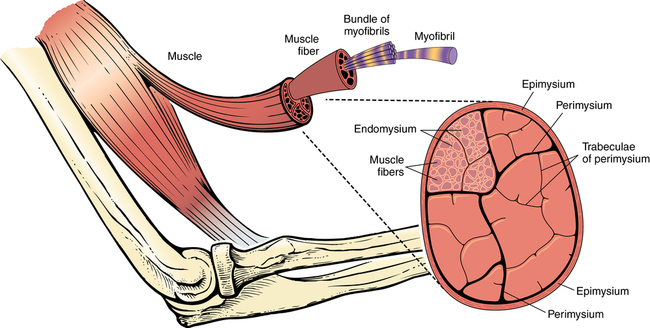

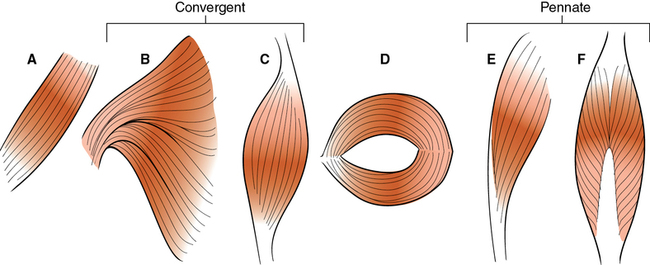

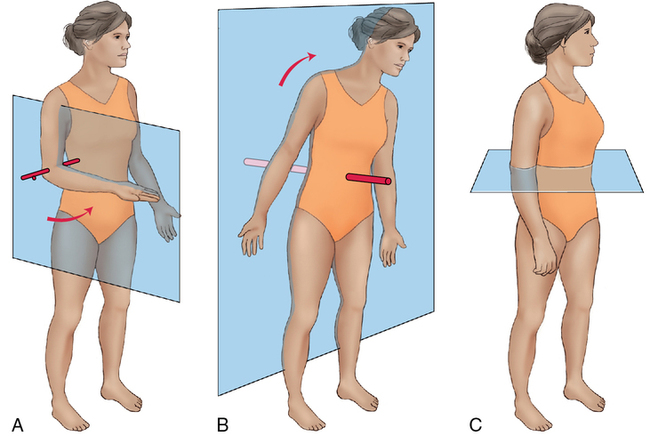

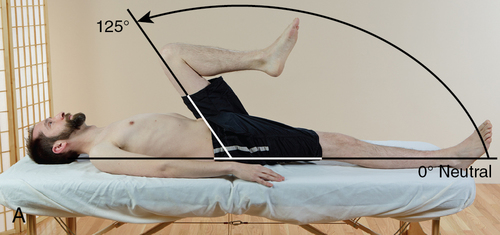

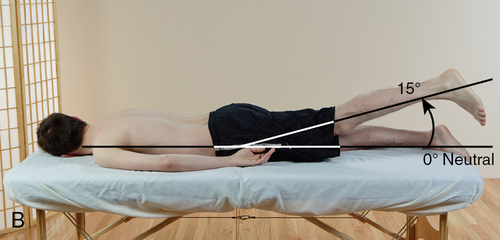

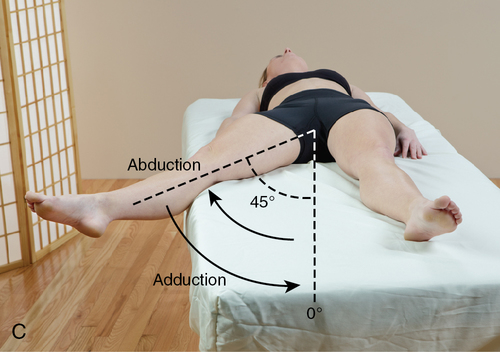

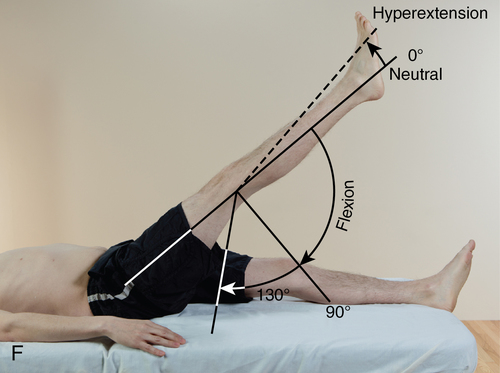

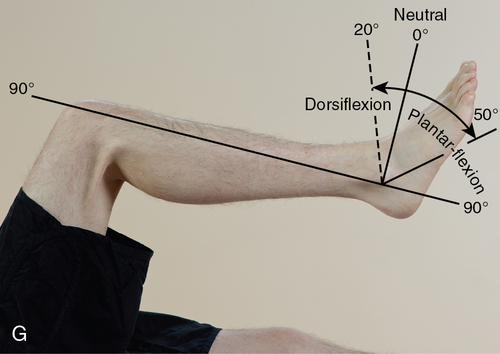

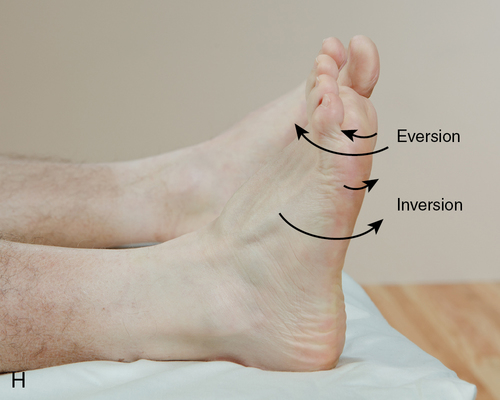

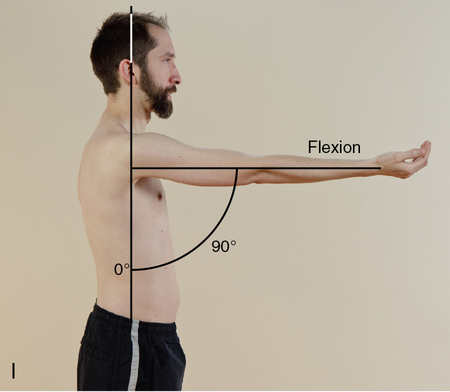

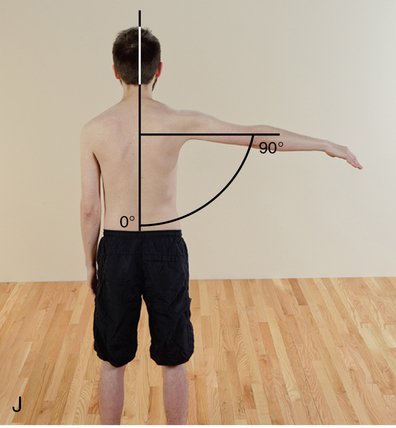

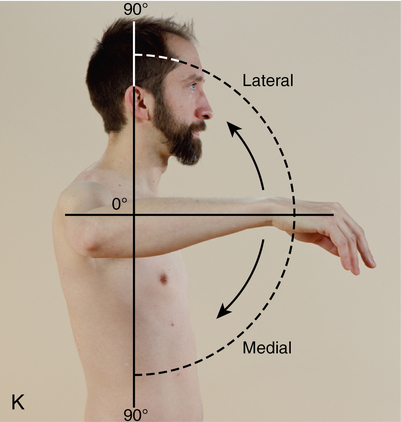

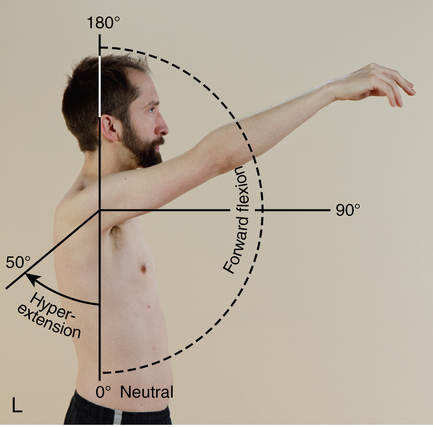

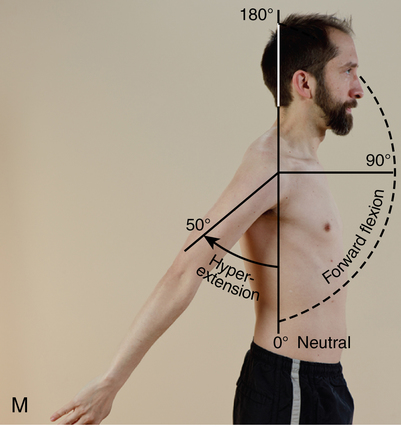

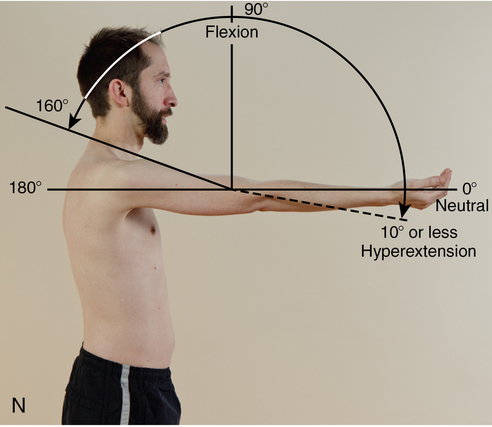

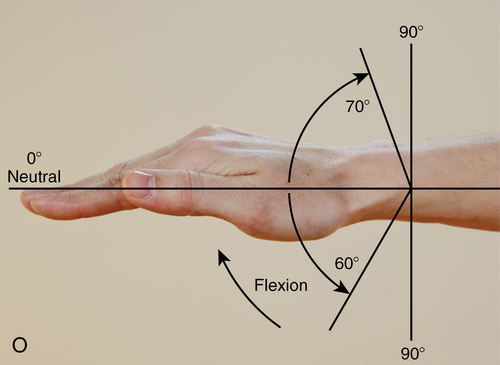

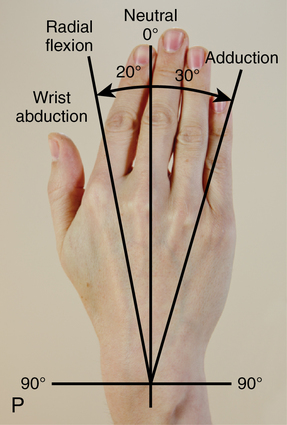

Tables 4-1 through 4-4 discuss common prefixes, root words, suffixes, and abbreviations. TABLE 4-1 TABLE 4-2 TABLE 4-3 TABLE 4-4 The cell is the smallest unit of independent function in the body. The basic cell structure consists of a lipid-based cell wall that contains cytoplasm and various organelles that perform cellular functions. It is useful to think of the cell wall as the skin; the nucleus as the brain; the organelles as organs of the body; and the cytoplasm as body fluid (Figure 4-1). The structural organization of the body follows a clear plan. Each human being has a vertebral column that supports the trunk and forms the central axis of the body. The spine also supports two body cavities: The dorsal cavity, which holds the brain inside the skull and the spinal cord in the vertebral column, and the ventral cavities, which are the combined thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic cavities (sometimes the abdominal and pelvic cavities are referred to as the abdominopelvic cavity). Human beings are bilaterally symmetrical beings, with left and right mirror images. Also, the body is segmented; this is most obvious in the vertebral column, ribs, and spinal regions of the body and surface anatomy (Figures 4-2 through 4-5). The following terms are used to describe the structural plan of the body: • Soma, somato: Root words that mean “the body,” as distinguished from the mind. Somatic organs and tissues are associated with the skin and the skeleton (e.g., bone and skeletal muscles, extremities, body wall) and commonly can be controlled voluntarily. • Axial: Areas and organs along the central axis of the body, including the head, neck, trunk, brain, spinal cord, and abdominal organs. • Appendicular: The limbs, joined to the body as lateral appendages. • Torso, trunk: Structures related to the main part of the body, including the chest, abdomen, and vertebral cavity. The head and limbs are attached to the trunk. Ventral cavities are located in the trunk. They include the following: • Thoracic cavity: Also known as the chest; found between the neck and the diaphragm and surrounded by the ribs. The mediastinum contains the heart, lungs, thymus gland, trachea, esophagus, and other structures and divides the chest into left and right parts. • Abdominal cavity: Also known as “the belly,” it is located below the diaphragm and enclosed within the abdominal muscles. This cavity contains the liver, kidneys, spleen, pancreas, stomach, and intestines. • Pelvic cavity: Inferior to the abdomen, inside the pelvic bones; contains a portion of the large intestine, as well as the bladder and the internal reproductive organs. • Viscera: Internal organs of the thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic cavities that are considered to be under involuntary control. • Membranes: Two types, associated with the regions of the trunk: Parietal membranes, lining the body cavities; and visceral membranes, covering the visceral organs. Terms related to the position of the body include the following: • Anatomic position: The body standing upright with the feet slightly apart, arms hanging at the sides, palms facing forward, and thumbs outward. This term is also used in Western medicine to describe the position of the body and the location of its regions and parts. The central axis of the body passes through the head and trunk. • Functional position: The body standing upright with the feet slightly apart, arms hanging at the sides, palms facing sides of body, and thumbs forward. • Erect position: The body standing. • Supine position: The body lying horizontally with the face up. • Prone position: The body lying horizontally with the face down. • Lateral recumbent position: The body lying horizontally on the right or left side. A transverse plane divides the body horizontally into two parts. These parts are described as superior (meaning above) and inferior (meaning below). The transverse plane runs perpendicular to the frontal and sagittal planes. Movement in the transverse plane consists of rotations—internal, external, and left and right rotation, and circumduction (Figure 4-7). Axis of movement An axis is a straight line around which an object rotates. Movement at the joint take place in a plane about an axis. There are three axes of rotation: Sagittal – passes horizontally from posterior to anterior and is formed by the intersection of the sagittal and transverse planes. Frontal – passes horizontally from left to right and is formed by the intersection of the frontal and transverse planes. Vertical – passes vertically from inferior to superior and is formed by the intersection of the sagittal and frontal planes. The following terms are commonly used to describe movement: • Flexion: A decrease in the angle between two bones as the body part moves out of the anatomic position; flexion is a sagittal plane movement. • Extension: An increase in the angle between two bones, usually moving the body part back toward the anatomic position; extension is a sagittal plane movement. • Hyperextension: A term that has two definitions: (1) any extension beyond normal or healthy extension; (2) any extension that takes the part farther in the direction of the extension, farther out of the anatomic position. • Abduction: Movement of the appendicular body part away from the midline; abduction is a frontal plane movement. • Adduction: Movement of the appendicular body part toward the midline; adduction is a frontal plane movement. • Right lateral flexion: Movement of the axial body part to the right; right lateral flexion is a frontal plane movement. • Left lateral flexion: Movement of the axial body part to the left; left lateral flexion is a frontal plane movement. • Right rotation: Partial turning or pivoting of the axial body part in an arc around a central axis to the right; right rotation is a transverse plane movement. • Left rotation: Partial turning or pivoting of the axial body part in an arc around a central axis to the left; left rotation is a transverse plane movement. • Medial rotation: Partial turning or pivoting of a body part of the appendicular body in an arc around a central axis toward the midline of the body; medial rotation is a transverse plane movement. • Lateral rotation: Partial turning or pivoting of a body part of the appendicular body in an arc around a central axis away from the midline of the body; lateral rotation is a transverse plane movement. • Circumduction: Not a movement, but a sequence of movements that turn or pivot the part through an entire arc, making a complete circle. (Note: Circumduction involves no rotation and is a multiplanar movement.) • Protraction: Pushing of a part forward in a horizontal plane. • Retraction: Pulling back of a part in a horizontal plane. • Elevation: Moving a part upward (superiorly). • Depression: Moving a part downward (inferiorly). • Supination: Movement of the forearm (at the radioulnar joint, not the elbow joint) that turns the palm anteriorly (upward), as when cupping a bowl of soup. • Pronation: Movement of the forearm (at the radioulnar joint, not the elbow joint) that turns the palm posteriorly (downward). • Inversion: Movement of the sole of the foot inward, toward the midline. • Eversion: Movement of the sole of the foot outward, away from the midline. • Plantar flexion: Movement of the foot downward (may also be called flexion). • Dorsiflexion: Movement of the foot upward (may also be called extension) (Figure 4-8). • Anterior (ventral): In front of, or in or toward the front. • Posterior (dorsal): Behind, in back of, or in or toward the rear. • Proximal: Closer to the trunk or the point of origin (usually used on the appendicular body only). • Distal: Situated away from the trunk, or midline, of the body; situated away from the origin (usually used on the appendicular body only). • Lateral: On or to the side, outside, away from the midline. • Medial: Relating to the middle, center, or midline. • Contralateral: The opposite side. • Superior: Higher than or above (usually used on the axial body only). • Inferior: Lower than or below (usually used on the axial body only). • Volar (palmar): The palm side of the hand. • Plantar: The sole side of the foot. • Varus: Ends bent inward; angulation of a part of the body such as the distal segment of a bone or joint inward toward the midline. For example, in a varus deformity of the knee, the distal part of the leg below the knee is deviated inward, resulting in a bowlegged appearance. • Valgus: Ends of the distal segment of a bone or joint bent outward. For example, a valgus deformity at the knee results in a knock-kneed appearance, with the distal part of the leg deviated outward. • Internal: An inside surface or the inside part of the body. • External: The outside surface of the body. • Deep: Inside or away from the surface. • Superficial: Toward or on the surface. • Sinistral (sinistro): Left; levo also is used to mean left. • General avoidance of application—Do not massage. • Regional avoidance of application—Do massage but avoid a particular area. • Application with caution, usually requiring supervision provided by appropriate medical or supervising personnel—Do massage, but carefully select the types of methods to be used, the duration of application, the frequency, and the intensity of the massage. The body is composed of tissues. A tissue is a collection of specialized cells that perform a special function. Histo is a root word meaning “tissue.” Histology is the study of tissue. The primary tissues of the body are the epithelial, connective, muscular, and nervous tissues (Figure 4-9). An organ is a collection of specialized tissues. An organ has specific functions, but it does not act independently of other organs (Table 4-5). TABLE 4-5 Systems of the Body and Their Important Organs The skeletal system consists of three types of tissue: Bone, cartilage, and ligaments. Bone is a dense connective tissue that is composed primarily of calcium and phosphate; os-, ossa-, oste-, and osteo- are all combining forms that mean “bone.” The human skeleton is composed of approximately 206 bones, and massage professionals must be familiar with most of them. Some of these bones include skull or cranium, cervical vertebrae, thoracic vertebrae, lumbar vertebrae, sacral vertebrae, coccygeal vertebrae, ribs, sternum, manubrium, body, xiphoid process, clavicle, scapula, humerus, ulna, radius, carpal bones, metacarpal bones, phalanges, pelvis, ilium, ischium, pubis, femur, patella, tibia, fibula, tarsal bones, and metatarsal bones. Other terms related to bones and landmarks on bones include malleolus, process, crest, insertion, joint, olecranon, origin, spine, trochanter, and tuberosity (Figure 4-10). Types of movement permitted by diarthrodial/synovial (freely movable) joints include the following: • Flexion: Bending that reduces the angle of a joint. • Extension: Straightening or stretching that increases the angle of a joint. • Abduction: Movement away from (ab-) the midline. • Adduction: Movement toward (ad-) the midline. • Pronation: Turning of the palm downward. • Supination: Turning of the palm upward (you can hold a bowl of soup in a supinated hand). • Eversion: Turning (-version) of the sole of the foot away from (e-) the midline (when you evert your foot, you move your little toe toward your ear). • Inversion: Turning (-version) of the sole of the foot inward (in-). • Plantar flexion: Bending of the plantar surface of the sole of the foot downward (plant your toes in the ground). • Dorsiflexion: Bending of the top or dorsal surface of the foot toward the shin. • Rotation: Rolling to the side (internal rotation: Rolling toward the midline; external rotation: Rolling away from the midline). • Circumduction: Making a cone; the ability to move the limb in a circular manner. • Protraction: Thrusting a part of the body forward (pro-). • Retraction: Pulling a part of the body backward (re-). • Elevation: Raising a part of the body. • Depression: Lowering a part of the body. • Opposition: The act of placing part of the body opposite another, as in placing the tip of the thumb opposite the tips of the fingers. Bursae are closed sacs or saclike structures (bursa) that usually are found close to the joint cavities. The lining of bursae often is similar to the synovial membrane lining of a true joint. Some bursae are continuous with the lining of a joint. The function of a bursa is to lubricate an area between skin, tendons, ligaments, or other structures and bones, where friction would otherwise develop (Figures 4-11 and 4-12 and Box 4-1). Each skeletal muscle is made up of parts. Most muscles have two ends (proximal and distal), which are attached to other structures, and a belly. Muscles cause and permit motion through the actions of contraction and relaxation. Table 4-6 presents a list of terms that are used to describe the movements of different types of muscles (Figure 4-13). TABLE 4-6 Terms for Describing Muscle by Movement A muscle that tries to initiate contraction is opposed by the following:

Anatomy and physiology

Medical terminology simplified

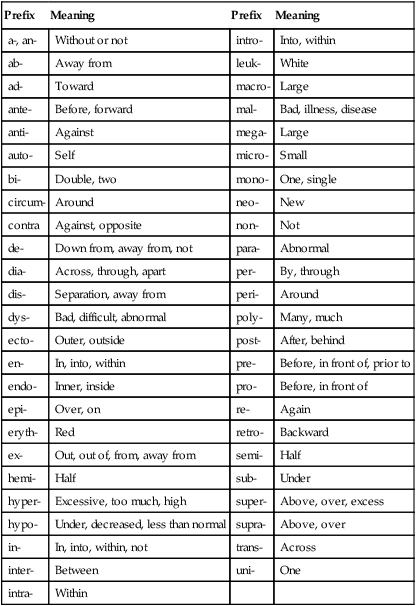

Prefix

Meaning

Prefix

Meaning

a-, an-

Without or not

intro-

Into, within

ab-

Away from

leuk-

White

ad-

Toward

macro-

Large

ante-

Before, forward

mal-

Bad, illness, disease

anti-

Against

mega-

Large

auto-

Self

micro-

Small

bi-

Double, two

mono-

One, single

circum-

Around

neo-

New

contra

Against, opposite

non-

Not

de-

Down from, away from, not

para-

Abnormal

dia-

Across, through, apart

per-

By, through

dis-

Separation, away from

peri-

Around

dys-

Bad, difficult, abnormal

poly-

Many, much

ecto-

Outer, outside

post-

After, behind

en-

In, into, within

pre-

Before, in front of, prior to

endo-

Inner, inside

pro-

Before, in front of

epi-

Over, on

re-

Again

eryth-

Red

retro-

Backward

ex-

Out, out of, from, away from

semi-

Half

hemi-

Half

sub-

Under

hyper-

Excessive, too much, high

super-

Above, over, excess

hypo-

Under, decreased, less than normal

supra-

Above, over

in-

In, into, within, not

trans-

Across

inter-

Between

uni-

One

intra-

Within

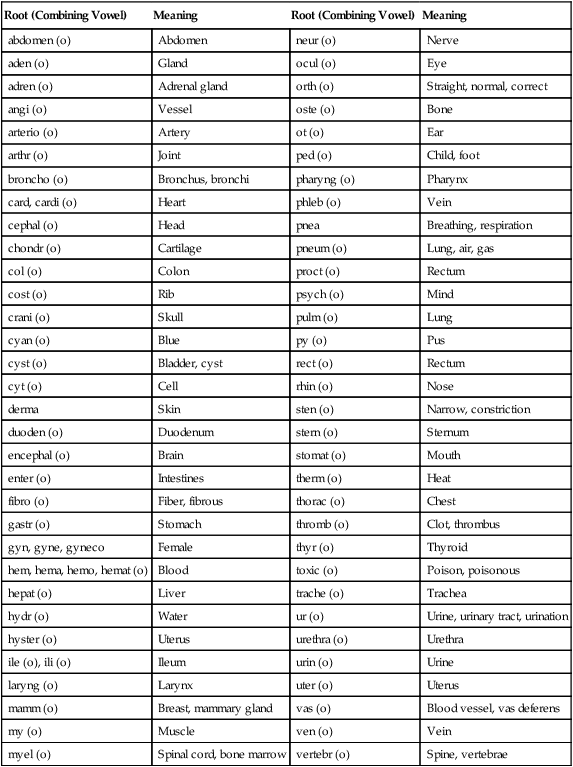

Root (Combining Vowel)

Meaning

Root (Combining Vowel)

Meaning

abdomen (o)

Abdomen

neur (o)

Nerve

aden (o)

Gland

ocul (o)

Eye

adren (o)

Adrenal gland

orth (o)

Straight, normal, correct

angi (o)

Vessel

oste (o)

Bone

arterio (o)

Artery

ot (o)

Ear

arthr (o)

Joint

ped (o)

Child, foot

broncho (o)

Bronchus, bronchi

pharyng (o)

Pharynx

card, cardi (o)

Heart

phleb (o)

Vein

cephal (o)

Head

pnea

Breathing, respiration

chondr (o)

Cartilage

pneum (o)

Lung, air, gas

col (o)

Colon

proct (o)

Rectum

cost (o)

Rib

psych (o)

Mind

crani (o)

Skull

pulm (o)

Lung

cyan (o)

Blue

py (o)

Pus

cyst (o)

Bladder, cyst

rect (o)

Rectum

cyt (o)

Cell

rhin (o)

Nose

derma

Skin

sten (o)

Narrow, constriction

duoden (o)

Duodenum

stern (o)

Sternum

encephal (o)

Brain

stomat (o)

Mouth

enter (o)

Intestines

therm (o)

Heat

fibro (o)

Fiber, fibrous

thorac (o)

Chest

gastr (o)

Stomach

thromb (o)

Clot, thrombus

gyn, gyne, gyneco

Female

thyr (o)

Thyroid

hem, hema, hemo, hemat (o)

Blood

toxic (o)

Poison, poisonous

hepat (o)

Liver

trache (o)

Trachea

hydr (o)

Water

ur (o)

Urine, urinary tract, urination

hyster (o)

Uterus

urethra (o)

Urethra

ile (o), ili (o)

Ileum

urin (o)

Urine

laryng (o)

Larynx

uter (o)

Uterus

mamm (o)

Breast, mammary gland

vas (o)

Blood vessel, vas deferens

my (o)

Muscle

ven (o)

Vein

myel (o)

Spinal cord, bone marrow

vertebr (o)

Spine, vertebrae

Suffix

Meaning

-algia

Pain

-asis

Condition, usually abnormal

-cele

Hernia, herniation, pouching

-cyte

Cell

-ectasis

Dilation, stretching

-ectomy

Excision, removal of

-emia

Blood condition

-genesis

Development, production, creation

-genic

Producing, causing

-gram

Record

-graph

Diagram, recording instrument

-graphy

Making a recording

-iasis

Condition of

-ism

Condition

-itis

Inflammation

-logy

Study of

-lysis

Destruction of, decomposition

-megaly

Enlargement

-oma

Tumor

-osis

Condition

-pathy

Disease

-penia

Lack, deficiency

-phasia

Speaking

-phobia

Exaggerated fear

-plasty

Surgical repair or reshaping

-plegia

Paralysis

-rrhage, -rrhagia

Excessive flow

-rrhea

Profuse flow, discharge

-scope

Examination instrument

-scopy

Examination using a scope

-stasis

Maintenance, maintaining a constant level

-stomy, -ostomy

Creation of an opening

-tomy, -otomy

Incision, cutting into

-uria

Condition of the urine

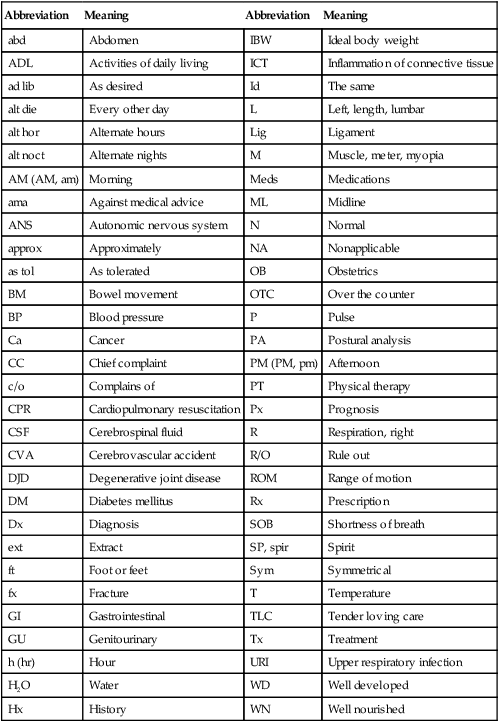

Abbreviation

Meaning

Abbreviation

Meaning

abd

Abdomen

IBW

Ideal body weight

ADL

Activities of daily living

ICT

Inflammation of connective tissue

ad lib

As desired

Id

The same

alt die

Every other day

L

Left, length, lumbar

alt hor

Alternate hours

Lig

Ligament

alt noct

Alternate nights

M

Muscle, meter, myopia

AM (AM, am)

Morning

Meds

Medications

ama

Against medical advice

ML

Midline

ANS

Autonomic nervous system

N

Normal

approx

Approximately

NA

Nonapplicable

as tol

As tolerated

OB

Obstetrics

BM

Bowel movement

OTC

Over the counter

BP

Blood pressure

P

Pulse

Ca

Cancer

PA

Postural analysis

CC

Chief complaint

PM (PM, pm)

Afternoon

c/o

Complains of

PT

Physical therapy

CPR

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Px

Prognosis

CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

R

Respiration, right

CVA

Cerebrovascular accident

R/O

Rule out

DJD

Degenerative joint disease

ROM

Range of motion

DM

Diabetes mellitus

Rx

Prescription

Dx

Diagnosis

SOB

Shortness of breath

ext

Extract

SP, spir

Spirit

ft

Foot or feet

Sym

Symmetrical

fx

Fracture

T

Temperature

GI

Gastrointestinal

TLC

Tender loving care

GU

Genitourinary

Tx

Treatment

h (hr)

Hour

URI

Upper respiratory infection

H2O

Water

WD

Well developed

Hx

History

WN

Well nourished

Cell anatomy review

Structural plan

Terms related to the structural plan

Anterior region of the trunk

Positions of the body

Body planes

Terminology of location and position

Kinesiology

Movement terms

Directional terms

Terms related to diagnosis and diseases

The structure of the body

Tissues

Organs and systems

System

Associated Organs

Musculoskeletal (can be classified separately as the skeletal, articular [joints], and muscular systems)

Bones, ligaments, skeletal muscles, tendons, joints

Nervous

Brain, spinal cord, nerves, special sense organs

Cardiovascular

Heart, arteries, veins, capillaries

Lymphatic

Lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils, thymus gland

Digestive

Mouth, tongue, teeth, salivary glands, esophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, liver, gallbladder, pancreas

Respiratory

Nasal cavity, larynx, trachea, bronchi, lungs, diaphragm, pharynx

Urinary

Kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, urethra

Endocrine

Endocrine glands: Hypothalamus, hypophysis (pituitary), thyroid, thymus, parathyroid, pineal, adrenal, pancreas, gonads (ovary or testis)

Reproductive

Female: Ovaries, uterine tubes (oviducts), uterus, vagina

Male: Testes, penis, prostate gland, seminal vesicles, spermatic ducts

Integumentary

Skin, hair, nails, sebaceous glands, sweat glands, breasts

The skeletal system

The articular system

Diarthrodial joints

Bursae

The muscular system

Skeletal muscle

Term

Definition

Adductor

Muscle that moves a part toward the midline

Abductor

Muscle that moves a part away from the midline

Flexor

Muscle that bends a part

Extensor

Muscle that straightens a part

Levator

Muscle that raises a part

Depressor

Muscle that lowers a part

Tensor

Muscle that tightens a part

Attachment terminology

Actions of muscles

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Anatomy and physiology

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue