Resection Arthroplasty of the Distal Radioulnar Joint

Jeffrey A. Greenberg

DEFINITION

The distal ulna resection attributed to Dr. William Darrach was described by Severinus in 1644, Rognetta in 1834, and Dupuytren in 1839.13 Malgaine in 1855 and Moore in 1880 also described distal ulna resections.9 Dr. William Darrach described the distal ulna resection that bears his name in 1912 and 1913 for the treatment of a posttraumatic volar distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) dislocation. This operation continues to have a place for the treatment of a variety of afflictions of the DRUJ.

In an effort to preserve some of the critical stabilizing soft tissue elements of the distal ulna, alternative treatments to complete ablation of the distal ulna have been developed.

Bowers2 published his results of the hemiresection interposition technique (HIT). This procedure differs from the Darrach in that the weight-bearing seat and pole are resected, preserving the styloid and soft tissue elements of the triangular fibrocartilage (TFC).

The essential element is matching the profile of the resected distal ulna to the medial side of the radius.

ANATOMY

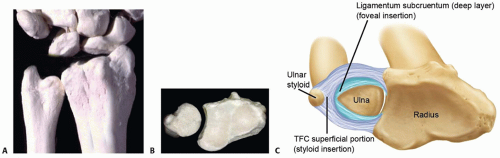

The DRUJ is formed by the articulation between the sigmoid notch and the head of the ulna (FIG 1A,B). The sigmoid notch is the articular cartilage surface on the medial aspect of the distal radius. This concave surface matches the corresponding convex surface or “seat” of the distal ulna. The arc of curvature of the sigmoid notch ranges between 47 and 80 degrees, with an average radius of 12 to 18 mm.

The articulation is constrained loosely, allowing both forearm rotation through a 150-degree arc and proximal and distal migration as well as dorsal and palmar translation of the ulna relative to the radius during forearm rotation. The articular cartilage-covered “cap” of the distal ulna can be divided into two functional regions. The seat of the ulna is the concave portion that articulates with the sigmoid notch. The arc of curvature ranges between 90 and 135 degrees, with an average radius of 8 to 13 mm. This region is covered by articular cartilage around 270 degrees of its surface. This is the region that supports the compressive loads of the distal radius during most activities of daily living and can be considered the fulcrum for load support.

The pole is the distal portion of the ulna that lies deep to the cartilaginous TFC. This region supports the centrum of the TFC as compressive loads pass from the ulnar carpus to the bony elements of the forearm. The medial distal portion of the ulna projects as the ulnar styloid. The base of the styloid contains the critical attachment of the deep layer of the TFC, the ligamentum subcruentum (FIG 1C).

Distal to this, and in a more peripheral location, is the attachment of the superficial layer of the TFC. The dorsal and volar portions of the TFC are thickened, forming the limbi of the TFC, the volar and dorsal radioulnar ligaments. These ligaments play critical roles in stabilizing the DRUJ.

PATHOGENESIS

Conditions that cause DRUJ degenerative change or altered DRUJ mechanics can lead to pain and DRUJ dysfunction. Most commonly, distal ulna resection is performed in

patients with inflammatory arthropathy, usually rheumatoid arthritis. Frequently, treatment of the DRUJ is performed in conjunction with other bone or soft tissue reconstructions.

DRUJ instability secondary to trauma or attritional changes of the supporting soft tissue elements can lead to degenerative change of this articulation.

Malunions of the distal radius can negatively affect the sigmoid notch by alterations in angulation or length and can disrupt DRUJ kinematics.

A less common cause of DRUJ arthritis is primary osteoarthritis, which may also lead to osteophytes and loose bodies.

Developmental conditions, such as Madelung deformity, can alter DRUJ joint mechanics. Painful forearm rotation and degenerative changes as well as ulnar impaction can develop.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with DRUJ problems present with pain and limited forearm rotation.

In isolated DRUJ arthrosis, the patients usually localize their pain at the DRUJ articulation.

In patients with concomitant associated pathology of the soft tissue elements and DRUJ stabilizers, the ulnar-sided pain is more diffuse.

Pain occurs with activities that require forearm rotation, such as turning doorknobs, turning keys in locks, starting a car, and opening jars. Lifting activities with the arm away from the body are difficult because the DRUJ is loaded in this position.

Limited forearm motion may be secondary to an arthritic DRUJ; however, other conditions (eg, capsular contracture) must be considered.

Prominence and deformity of the distal ulna is common in patients with inflammatory changes and in patients with distal radius fracture malunions.

Inspection is usually unremarkable in patients with isolated DRUJ osteoarthritis. In contrast, DRUJ deformity and prominence is common in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.19 Fullness due to synovial proliferation may be visible and secondary attritional changes of surrounding soft tissue elements, such as extensor tendon rupture, can lead to abnormal hand posture.

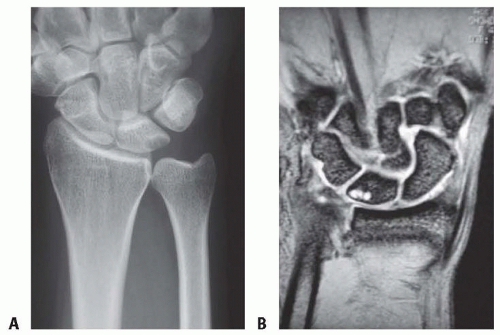

Radius malunions with shortening and angulation produce visible prominence of the distal ulna (FIG 2).

Tenderness with pressure on the dorsal aspect of the DRUJ is frequently elicited. In patients with associated impaction or TFC pathology, tenderness may be more diffuse. Palpable crepitance with rotation is often present. Compressing the distal ulna into the sigmoid notch while rotating the forearm elicits painful crepitation and is suggestive of arthrosis.

Pain on the ulnocarpal stress test is indicative of TFC pathology.

Pain on application of pressure in the interval between the ulnar styloid and flexor carpi ulnaris tendon is indicative of TFC or capsuloligamentous pathology (foveal sign).22

Piano key maneuver: Visible dorsal winging or instability of the distal ulna is noted. If the ulna is dorsally prominent, the examiner can manually reduce the ulna into the sigmoid notch. The ulna spontaneously dorsally subluxates when pressure is removed. Winging is associated with loss of structural support of the DRUJ.

Grip strength is frequently limited secondary to painful compressive loading of the DRUJ.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs are usually sufficient to supplement physical examination findings. It is essential to obtain a neutral forearm rotation posteroanterior (PA) and lateral views (FIG 3A) to accurately assess ulnar variance, styloid morphology, inclination of the sigmoid notch, and position of the ulnar styloid. These factors are important in selecting the appropriate surgical management for disorders of the distal ulna.

Thin-section computed tomography (CT) scanning can provide useful additional information about DRUJ articular surfaces and subluxation.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation is rarely necessary to diagnose arthritic disorders of the DRUJ but can be useful when detailed information about the radioulnar ligaments or surrounding bony ligaments of the TFC is necessary (FIG 3B).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

DRUJ arthritis

Inflammatory

Osteoarthritis

Traumatic

Iatrogenic (eg, altered joint mechanics after ulnar shortening)

DRUJ instability

TFC tears

Ulnar impaction

Lunotriquetral ligament tears or instability

Extensor carpi ulnaris tendinitis

Extensor carpi ulnaris instability

Pisotriquetral disorders

Nerve entrapment (canal of Guyon)

Nerve injury (eg, neuromas of dorsal ulnar sensory nerve)

Madelung deformity with DRUJ dysfunction

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Patients with mild symptoms and minimal functional impairment may be managed with oral anti-inflammatories, intra-articular injections, or splinting.

Splinting must include the elbow to eliminate forearm rotation.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Maintaining the distal ulna has gained recent popularity as resection can be associated with considerable postoperative complications and functional disability. Meticulous attention to preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative detail is essential for a successful result.

Adjunctive Procedures

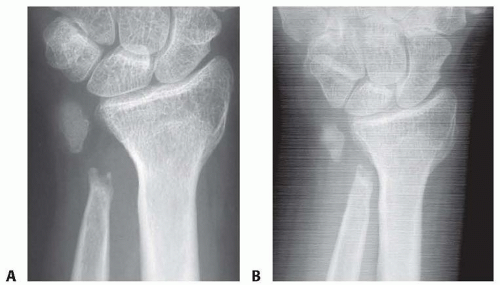

After complete or partial resection of the distal ulna, convergence between the radius and ulna can develop.14 Loss of the weight-bearing fulcrum of the ulna seat can yield convergence with grip or loaded lifting with the arm extended and the forearm in neutral rotation (FIG 4).

Adjunctive procedures incorporate some type of tendon transfer or interpositional material to stabilize the resected ulnar stump (FIG 5). The pronator quadratus, extensor carpi ulnaris, and flexor carpi ulnaris tendons have been used alone and in combination.

In addition to tendon transfer, some authors have recommended suturing the ulnar capsule to the dorsal ulnar stump to help stabilize the remaining ulna.21 Kleinman and Greenberg11 advocated use of a dynamic pronator quadratus interosseous transfer in conjunction with an extensor carpi ulnaris distal tenodesis for failed distal ulna resections. More recently, allograft soft tissue interposition has been advocated12 as well as distal ulna implant arthroplasty.27

Most adjunctive procedures have been described for treatment of a failed symptomatic Darrach procedure; however, they can be incorporated during the initial surgery. Symptomatic convergence tends to develop in a relatively younger, higher demand patient. If distal ulna resection is necessary in this patient population, use of an adjunctive procedure is recommended.

Preoperative Planning

The ideal candidate for a Darrach resection is a patient with a relatively low-demand upper extremity that does not require the load-bearing DRUJ.

Coexisting pathology is frequently present in patients with distal ulna dysfunction, especially in patients with inflammatory arthropathy.19 Assessing for associated tenosynovitis and tendon ruptures is necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree