Replantation of Digits

Samir Mardini

Kuang-Te Chen

Fu-Chan Wei

Indications/Contraindications

Replantation is defined as reattachment and revascularization of a completely amputated part, whereas revascularization is defined as restoration of arterial inflow or venous outflow to or from a part that is incompletely amputated. In revascularization cases, it is of utmost importance that the true severity of the injury is not underestimated due to the grossly intact image of the injured finger. The introduction and improvements in microsurgical instrumentation and techniques have lead to successful revascularization and replantation of amputated parts as distal as the finger tip and pulp. Overall, the results of finger replantation are encouraging and have provided many amputation victims with extremely rewarding results.

Amputations of upper extremity digits are devastating for the patient who is initially stunned by the events of the trauma. Therefore, care is taken to discuss the situation in a gentle and thoughtful manner, considering that the patient has just lost a part of the upper extremity, and that this loss might be permanent if the reconstructive effort is not indicated or is unsuccessful. Generally accepted indications for finger replantation include amputations of the thumb in almost every situation, a single digit with the level of injury distal to the superficialis insertion, multiple digits, and any amputation in children (Table 37-1). The patient’s desires have a strong influence on the approach.

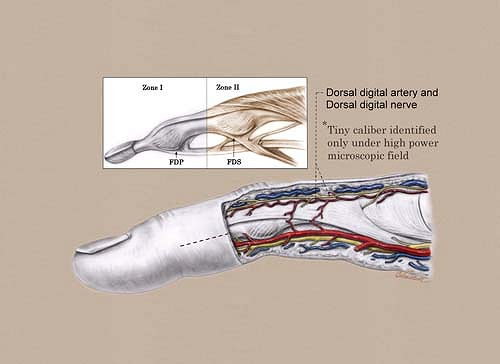

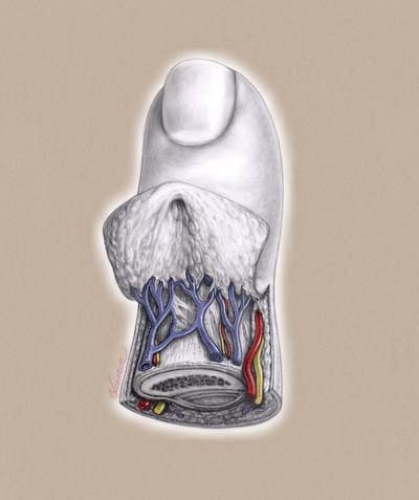

Success in replantation is based on the functional outcomes as judged by objective parameters such as strength, range of motion, and sensory function, and not on the survival of the replanted or revascularized parts alone; therefore, the potential outcome must be considered for each individual patient. The potential for a long operative procedure, immediate or late failure, the potential requirement of regional or distant tissue flaps to complete the reconstruction, and the possible need for multiple procedures even after survival of the replants should be included in the formula for decision making and discussed with the patient and his or her family. The location, mechanism of injury, number digits involved, level of injury, condition of the amputated part, condition of the hand, length of ischemia time, the patient’s general health, age, and associated injuries, and the patient’s desires dictate the course of action. One advantage of replanting any digit is prevention of neuroma formation. A thorough knowledge of the anatomy and adequate exposure of structures aids in attaining optimal results (Figs. 37-1 and 37-2).

The thumb is the most important single digit, and its replantation is the most rewarding since provision of a post for opposition, even with lack of motion at the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints, is significant. In avulsion cases, the defects of the vessels and nerves may be segmental and the use of vein grafts for the arteries and veins, and nerve grafts or vein grafts for the nerves, may be required. The long nerve stumps of the amputated thumb can be anastomosed to the dorsal sensory nerves in the first web space, to a transposed nerve from the index finger, or to the more proximally located nerve stumps using nerve grafts. Despite the fact that sensory return may only be protective in nature, the replantation of thumb avulsion injuries usually results in significant improvement in function.

Patients presenting with multiple digit amputations are candidates for replantation, and efforts are made to replant all fingers with potential for good functional outcomes. The surgeon uses his or her judgment in deciding the location where an amputated part should be replanted. Replanting a digit onto the stump of the thumb is the first priority, and the other amputated digits should be replanted with the idea that a better grip is achieved when the long, ring, and small fingers are replanted without

gaps between the digits, and better fine pinch is achieved when the index and long finger are replanted. Efforts are made to replant each amputated digit to its natural position; however, less severely damaged amputated digits may be better placed onto a stump that is less damaged and is located in a more functionally significant position. For example, in a case of multiple digit amputations with involvement of both the thumb and index finger, in which the amputated thumb has sustained irreparable damage, the index finger is replanted to the stump of the thumb. After the thumb position has been filled, the replantation should begin with the one most appropriate for the patient’s daily activities and functional needs at work.

gaps between the digits, and better fine pinch is achieved when the index and long finger are replanted. Efforts are made to replant each amputated digit to its natural position; however, less severely damaged amputated digits may be better placed onto a stump that is less damaged and is located in a more functionally significant position. For example, in a case of multiple digit amputations with involvement of both the thumb and index finger, in which the amputated thumb has sustained irreparable damage, the index finger is replanted to the stump of the thumb. After the thumb position has been filled, the replantation should begin with the one most appropriate for the patient’s daily activities and functional needs at work.

Table 37-1. Indications and Contraindications for Finger Replantation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

Single-digit amputations distal to the insertion of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tendon (zone I) yield good outcomes following replantation, with little need for secondary surgery, even if the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint requires fusion. In some instances, venous outflow cannot be

reconstituted and postoperative leech therapy or heparinization and purposeful exsanguination can achieve digit survival. Four millimeters of dorsal skin proximal to the nail fold must be present for adequate vein size to be repaired. Tsai, McCabe, and Maki described their technique of finger tip replantation, which used leech therapy and other methods of decongesting the finger when venous congestion developed postoperatively. These authors noted a 69% survival rate, a 75% rate of return of some form of two-point discrimination, and an average range of motion of the DIP joint of 56 degrees. Replantation of a single-digit amputation at a level proximal to the insertion of the flexor superficialis tendon and distal to the first annular pulley (zone II) often results in stiffness of the proximal and DIP joints and limited motion of the finger, with the replanted finger interfering with movement of the other fingers. Therefore, single-digit replantation may be only suitable for well-motivated individuals who are willing to undergo appropriate postoperative physical rehabilitation for a maximal functional recovery. Unless they are highly motivated, concerned about cosmetic outcome, or are children, patients are not usually replanted in this situation, as they often require secondary surgery and end up with disappointing outcomes.

reconstituted and postoperative leech therapy or heparinization and purposeful exsanguination can achieve digit survival. Four millimeters of dorsal skin proximal to the nail fold must be present for adequate vein size to be repaired. Tsai, McCabe, and Maki described their technique of finger tip replantation, which used leech therapy and other methods of decongesting the finger when venous congestion developed postoperatively. These authors noted a 69% survival rate, a 75% rate of return of some form of two-point discrimination, and an average range of motion of the DIP joint of 56 degrees. Replantation of a single-digit amputation at a level proximal to the insertion of the flexor superficialis tendon and distal to the first annular pulley (zone II) often results in stiffness of the proximal and DIP joints and limited motion of the finger, with the replanted finger interfering with movement of the other fingers. Therefore, single-digit replantation may be only suitable for well-motivated individuals who are willing to undergo appropriate postoperative physical rehabilitation for a maximal functional recovery. Unless they are highly motivated, concerned about cosmetic outcome, or are children, patients are not usually replanted in this situation, as they often require secondary surgery and end up with disappointing outcomes.

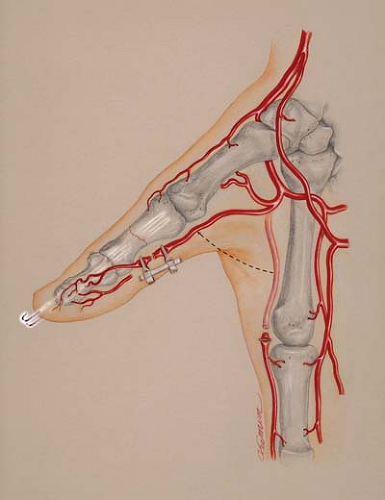

Ring avulsion amputations present with segmental injuries of structures such as arteries, veins, and nerves; therefore, vein and nerve grafts are often necessary to bridge the gaps after debridement of unhealthy appearing neurovascular tissue. Otherwise, transposition of the neurovascular bundle from an adjacent digit (Fig. 37-3) or the use of arteriovenous shunting for inflow to the replanted digit can also yield successful outcomes. Most surgeons consider ring avulsion amputation patients to be poor candidates for replantation; however, replantation of an avulsed digit still can be attempted if the patient insists on replantation and he or she understands the likeliness of a suboptimal outcome.

The mechanism of injury plays an important role in decision making. Sharp, incisive injuries predict better functional outcomes than crush or avulsion injuries.

In elderly patients and patients with compromised medical conditions, the decision is based on the balance between the risk of undergoing the surgery, the functional outcome anticipated, and the significance of the replantation to the patient. Life-threatening injuries and significant medical conditions that preclude long anesthesia times are contraindications to digit replantation. Microsurgical replantation in children or infants is indicated and can yield good functional outcomes. In elderly patients, the surgeon should take into consideration the potential systemic insult from the anesthesia and operation, the arteriosclerosis of vessels, and the poorer potential of functional recovery.

Warm ischemia times of less than 8 to 12 hours and cold ischemia times of less than 30 hours, measured from the time of amputation to the time of restoration of blood flow, are tolerated in digit replantation. Survival of replanted digits has been reported after as long as 42 hours of warm ischemia and 94 hours of cold ischemia. Immediate and proper cooling of the amputated part lengthens tissue survival.

A preoperative history of cigarette smoking does not seem to confer as negative an effect on the replantation as postoperative smoking. It has been shown to have significant negative effects on blood flow for up to 3 months. If the patient is unwilling to stop cigarette smoking, this could be considered a contraindication.

Amputated digits that are not commonly replanted are ones that are severely crushed or damaged, severely contaminated, have undergone multiple-level amputations, or are those of patients with multiple associated traumas or severe medical problems.

Preoperative Planning

A team approach is essential to the success of replantation. The transport team and the emergency room physicians should place the amputated part in appropriate dressings and arrange efficient transport to a center that has a replantation team. This team includes microvascular surgeons, anesthesiologists, operating room personnel and facilities, a microscope, and postoperative monitoring capabilities.

Minimal time should be wasted in obtaining unnecessary examinations. Many of the studies can be performed on the patient while the operating room is being prepared and, subsequently, the amputated finger is being prepared. If the operating room is ready and the patient is not, the finger can be taken to the operating room and prepared for replantation.

Obtaining a history and physical examination is necessary to aid in determining indications for surgery and avoiding postoperative complications and disappointing outcomes. Current events related to the injury are detailed, including the time and mechanism of injury, the location and conditions where the trauma took place, and the way the amputated digits or stumps were handled prior to admission. Information regarding the patient’s general condition, including other injuries that occurred in relation to the current trauma and the patient’s medical and surgical history, are obtained. The general examination of the patient is performed to exclude other major injuries. The amputated digit and the stump are examined in the emergency room. This examination is performed without digital blocks, which may cause injury to structures essential for successful replantation.

The amputated part is carefully preserved in a cool condition to minimize damage from ischemia. The amputated part is wrapped in gauze moistened with Ringer’s lactate or saline solution, and placed in a plastic bag or specimen cup, which is then placed on ice. The amputated part is never placed directly on or immersed in ice or ice water, as this can cause freezing and permanent damage to the tissues.

Radiographs of the amputated digit and hand are taken to evaluate the condition of the bones and the presence of foreign bodies. The patient is kept in a warm environment, provided with adequate hydration, tetanus prophylaxis, and broad-spectrum antibiotics that are appropriate for the mechanism of injury and condition of the wound.

A discussion with the patient and the patient’s family should include the risks of anesthesia, possibility of long operating times, potential need for blood transfusions, requirement for postoperative hospitalization, possibility of further surgery to salvage the finger in case of vascular compromise, the likely need for secondary procedures such as tenolysis, and the definite need for extensive physical rehabilitation postoperatively to achieve optimal outcomes. Patients are informed of the possibility that revision of the stump and closure of the wound might be performed; that vein grafts, nerve grafts, skin grafts, local flaps, regional flaps, or free flaps might be necessary to complete the reconstruction; and that bone shortening is often necessary in the primary reconstruction. The patient is made aware that there is a chance of immediate or late failure of the reconstructive effort and that other options for rehabilitation, such as prosthetic devices, might need to be resorted to in the future. Finally, if the patient is a smoker, he or she is told that smoking can affect the outcome and that postoperative smoking for up to 3 months can be detrimental to the final outcome of the surgery. The patient is given clear and realistic expectations regarding the expected outcomes.

Appropriate consultations with medical specialists are obtained. If a psychiatric disorder is suspected, a psychiatric consultation is obtained which in some circumstances might affect the decision as to whether to proceed with the replantation.

If an operating room is available, the amputated part is taken there first, examined under magnification, and set up for replantation while the patient is being prepared and anesthetized. Replantation is performed as soon as possible to shorten the ischemic time.

Surgery

Patient Positioning

The patient is placed in a supine position with the arm abducted and placed over an arm table. A tourniquet is placed high up on the arm and on one of the lower extremities (in case vein, nerve, or skin grafts are required). Appropriate warming devices are placed to maintain normal body temperatures throughout the procedure.

General anesthesia is recommended, as replanting each digit requires between 2 to 4 hours to complete, and this usually becomes uncomfortable for the patient when an axillary block is performed. A brachial plexus block can be used to decrease the requirement for pain medication and decrease the incidence of vascular spasm in the operating room and postoperatively. Some authors use a brachial plexus block in addition to sedation in adults and older children with single-digit amputations in one extremity who are thought to be non-anxious and may tolerate 2 to 5 hours of immobility.

Preparation and cleansing of the stump and amputated part are performed using a povidone-iodine solution followed by copious irrigation with normal saline. A tourniquet is placed on the involved arm and one leg, and both are prepared and draped.

Technique

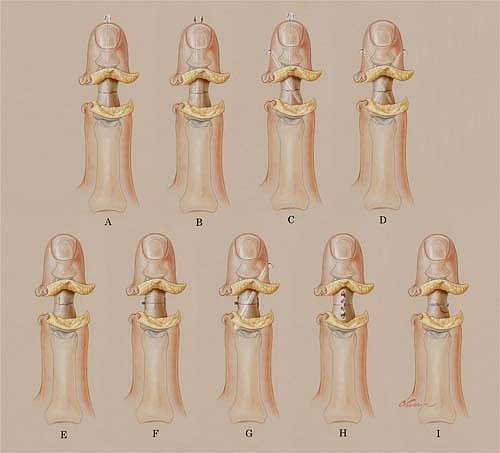

A two-team approach is used whenever possible, with one team working on the amputated part and the other working on the hand. The operative sequence for digit replantation varies slightly among surgeons and depends on the individual situation and ischemia time; however, our general routine is (1) identification of structures, (2) debridement, (3) bone shortening and fixation (Fig. 37-4), (4) repair of the extensor tendon, (5) repair of flexor tendons, (6) anastomosis of the artery, (7) coaptation of nerves, (8) anastomosis of veins, and (9) closure of the wounds.

Identification of Structures

During the dissection, the amputated part can be kept cool by placing it over a cooled apparatus. Bilateral mid-axial incisions are made, and the volar skin flap and dorsal skin flap are elevated, folded back, and sutured in position (see Fig. 37-2). If one team is performing the surgery, the exploration begins by identifying the neurovascular bundles and other structures in the amputated part using an operating microscope. High magnification minimizes inadvertent injury to important structures and decreases the chances of vasospasm. The digital arteries, one or two dorsal veins, and the digital nerves are identified and tagged with 6-0 sutures. The extensor and flexor tendons are located, trimmed, and tagged. If there is no artery available in the amputated part for anastomosis as is sometimes the case with ring avulsion amputations, the options for replantation become more limited. The use of an afferent arteriovenous shunt for the revascularization of unfavorable amputations of fingertips and distal phalanges may be an option (Fig. 37-5), or the replantation effort is halted and a revision and closure of the stump is performed (12,28–30).

Debridement

All non-viable tissue is excised while being careful not to cause inadvertent injury to important structures including the pulleys, particularly the A2 and A4 pulleys.

Bone Shortening and Fixation

Without excessive periosteal stripping, the bone is trimmed to provide surfaces that allow for good bone contact during fixation. Bone shortening also allows for direct vessel or nerve repair without tension, minimizes the need for using vein grafts and nerve grafts, and permits a more relaxed skin closure as postoperative edema can create compression of the vessels. Preservation of 5 to 10 mm of bone near a joint helps increase the range of motion that can be achieved. In traction avulsion amputations, the bone may require further shortening (19,36). Amputations through a joint are commonly treated with arthrodesis at the time of replantation. If this is not performed in the initial setting, eventual use of a silastic arthroplasty can solve some problems related to joint stiffness but is insufficient when the collateral ligaments are not present or do not provide adequate stability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree