Repair of Acute Digital Flexor Tendon Disruptions

Christopher H. Allan

Matthew Iorio

DEFINITION

Flexor tendon injuries can occur in any of the five described zones within the finger, hand, wrist, or forearm. All such injuries require surgical repair to restore active finger flexion.

The most challenging injuries to manage are those in zone II, where two flexor tendons occupy a narrow fibro-osseous sheath. Successful repair requires meticulous technique and a careful postoperative therapy regimen balancing the risks of adhesion formation versus rupture.

ANATOMY

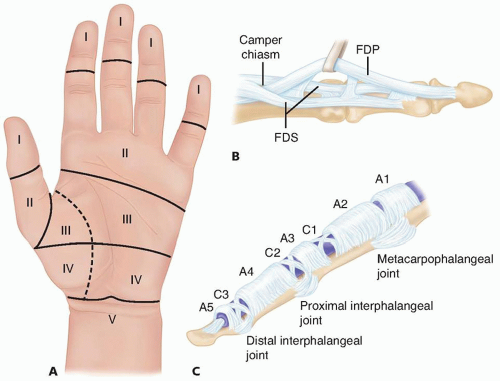

The flexor tendons form two layers in the forearm (zone V; FIG 1A), with the thumb’s flexor pollicis longus (FPL) and the fingers’ flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) muscles deep to the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) muscle. At the wrist, the FPL and FDP tendons remain deep, with the index and small FDS tendons above, and the middle and ring FDS tendons most superficial.

The median nerve runs down the forearm beneath the fascia of the FDS on its undersurface, becoming superficial within the carpal tunnel just proximal to the volar wrist crease (zone IV), with the flexor tendons closely packed together.

Exiting the carpal tunnel, the flexor tendons cross the palm (zone III) toward the individual digits. Here, the lumbrical muscles take origin from the radial side of the finger FDP tendons and continue deep to the deep transverse intermetacarpal ligaments.

FIG 1 • A. Flexor tendon zones (I to V). B. Flexor tendon anatomy in zone II. C. Flexor sheath pulley anatomy and distribution in zones I and II.

The two tendons of each nonthumb digit (the thumb has just the FPL) enter the fibro-osseous sheath (zone II) at the level of the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint. The two FDS slips then rotate laterally and dorsally, with the medial FDS slips forming the decussation termed the chiasm of Camper, through which the FDP passes from deep to superficial (FIG 1B).

The two lateral slips of the FDS then insert along the proximal aspect of the volar surface of the base of the middle phalanx, and the FDP proceeds distally to insert along the volar surface of the base of the distal phalanx.

The flexor sheath extends from the level of the MP joint to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. Multiple condensations of discrete fibers are found along its course and are named as either annular or cruciate pulleys, reflecting the orientation of the fibers forming the pulley (FIG 1C).

The thicker annular (A1 through A5, from proximal to distal) pulleys hold the tendons close to bone, whereas the more slender cruciate (C1 through C3) pulleys collapse with digit flexion, allowing the sheath to shorten without buckling. Zone II is that part of the sheath where both FDS and FDP tendons are present and zone I is distal to the FDS insertion.

Tendon nutrition within the sheath is provided indirectly via synovial fluid and directly via vascular inflow through mesenteric folds called vincula, with one vinculum longus

and one vinculum brevis to each flexor tendon. Following lacerating injury, these vincula help to further limit the proximal retraction of the flexor tendons in the fingers. This mechanism is absent in the thumb, as the FPL lacks a defined vincula, and therefore, proximal counter incisions are frequently required to retrieve the tendon following complete transection.

PATHOGENESIS

Most acute flexor tendon injuries are the result of open trauma, with sharp transection of the tendon. In such cases, other structures are often injured as well. In particular, examination should include assessment of sensibility and capillary refill to identify injury to the digital nerves and vessels that would affect preoperative planning.

A less common injury mechanism is closed avulsion of the FDP from its distal attachment to bone. The term jersey finger is sometimes used for this injury, as it is often the result of an athlete’s fingers forcibly flexing to grab an opponent’s jersey, followed by sudden and forceful extension of the DIP joint against resistance as the opponent pulls away. This avulsion injury is addressed elsewhere.

NATURAL HISTORY

Flexor tendon injuries require surgical repair to restore active digit flexion. Early repair is crucial, with several studies pointing to better results when repairs are performed within the first 7 days after injury.3,7

Outcomes aside, as a practical matter, it is easiest to repair the tendon before proximal tendon retraction occurs, requiring additional incisions. Late repair with tendon retraction and muscle shortening can also result in tension at the repair site, leading to gapping of the repair (which increases the failure rate) or influencing the surgeon to splint the wrist or digits in excessive flexion, leading to joint contractures.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Methods for examining the hand or upper extremity with an acute flexor tendon injury

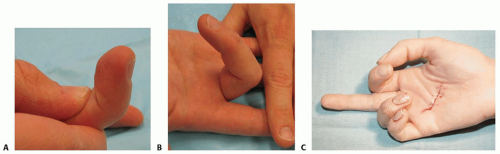

Isolate FDP: While maintaining the injured digit’s proximal interphalangeal joint extended, the examiner asks the patient to actively flex the DIP joint (FIG 2A).

FIG 2 • A. Isolation of DIP flexion to test FDP. B. Isolation of proximal interphalangeal flexion to test FDS integrity. C. Loss of normal flexion cascade after tendon laceration in palm.

Isolate FDS: While maintaining all uninjured digits in full extension, the examiner asks the patient to actively flex the injured digit’s proximal interphalangeal joint (FIG 2B).

Uncooperative or unresponsive patient

Tenodesis effect: The examiner extends the wrist; flexion is observed at the interphalangeal joints if the flexor tendons are intact.

Forearm compression: Pressure applied to flexor tendon muscle bellies results in interphalangeal joint flexion if flexor tendons are intact.

The examiner inspects for normal flexion cascade (FIG 2C).

Examination of the digit to rule out associated digital nerve injury is required.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Laceration

Affected digit held in unopposed extension

Inability to actively flex interphalangeal joints (if both tendons are cut), isolated DIP joint (if FDP only is cut), or isolated proximal interphalangeal joint (if FDS only is cut)

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The sudden loss of active flexion after a laceration overlying the flexor sheath almost always represents a tendon injury. Radiographs should be obtained to rule out associated fractures that would require treatment at the time of tendon repair. Lacerations due to glass, metal fragments, and so forth should be imaged to localize any residual foreign bodies for removal.

In the setting of a closed injury with the sudden loss of active flexion, one must consider the possibility of a tendon avulsion from its insertion. Radiographs may demonstrate an avulsed fleck of bone. In the more common cases of an FDP avulsion, this bone fragment may remain in the region of the distal phalanx or may be pulled proximally into the flexor sheath. If no bony fragment is seen on a plain radiograph and the diagnosis is still in doubt, ultrasound may help.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Pain after injury may cause a patient (especially a child) to hold a digit or hand immobile, mimicking tendon injury.

Testing for the tenodesis effect (digits passively flex with wrist extension) or compressing the flexor musculature in the forearm to assess for digit flexion should help with diagnosis in these situations.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

There is no nonoperative means of restoring active flexion to a digit whose flexors have been cut, as the tendon ends retract and do not heal to one another.

If a flexor tendon laceration is encountered within the first 4 weeks after injury, it is probably worthwhile attempting primary repair. After that time, discussion should be held with the patient regarding other options.

For late presentation of an isolated FDP laceration in zone I, it may be practical to do nothing, as full proximal interphalangeal motion should still be present. If the DIP joint is or becomes unstable, a DIP joint fusion or tenodesis of the distal FDP stump can be performed. One large series reported successful primary tendon grafting for isolated FDP lacerations even in zone II, but this is not widely performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree