Repair following Traumatic Extensor Tendon Disruption in the Hand, Wrist, and Forearm

David B. Shapiro

Mark A. Krahe

Nathan A. Monaco

DEFINITION

Traumatic disruptions of the extensor mechanism represent a broad spectrum of injuries, frequently occurring because of the tendons’ superficial location, and frequently associated with concomitant injury to bone, skin, and joint.17

Repair can be technically demanding. The extensor tendons are thin, have limited excursion, and are intolerant of shortening, especially in the digits.

Reconstruction of subacute and chronic extensor tendon injuries are more challenging and less effective than early repair, underscoring the importance of appropriate treatment in the acute setting.

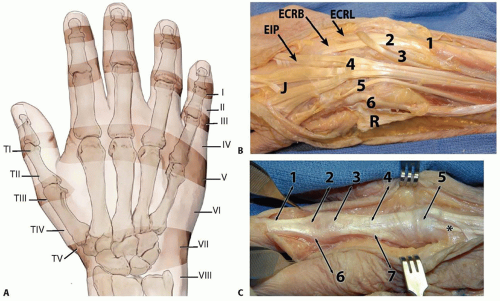

FIG 1 • A. Extensor tendon zones of injury. B,C. The digits are to the left and the wrist is to the right. B. The top of the figure is radial and the bottom is ulnar. Wrist and hand extensor tendon anatomy, with numbers (1 to 6) to identify the extensor tendon compartments. R is the reflected extensor retinaculum and J is a junctura tendinum. Note the combined EDC tendon to the ring and small fingers. In the fourth compartment, the EIP tendon is deep to the EDC tendons and has more distal muscle fibers. In the hand, it is just deep and ulnar to the index EDC tendon. See Table 1 for more details. C. The digital extensor mechanism. 1) Terminal tendon. 2) Triangular ligament. 3) PIP joint. 4) Central slip tendon. 5) Sagittal band. 6) Lateral band, which will become the terminal tendon distally. 7) Conjoined lateral band, with fibers to the base of middle phalanx and to the lateral band. This patient has an unusual proprius tendon to the long finger (asterisk), passing ulnar to the EDC tendon and beneath the junctura. |

ANATOMY

The extensor mechanism is divided into eight zones in the fingers and five in the thumb, numbered from distal to proximal.

Even-numbered zones are over bones and odd-numbered ones are over joints.

Extrinsic extensors (FIG 1B)

Digital and wrist extensor muscles originate from the lateral epicondyle and condyle, with musculotendinous junctions 3 to 4 cm proximal to the wrist joint. The extensor indicis proprius (EIP), extensor pollicis longus (EPL),

abductor pollicis longus (APL), and extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) all originate more distally from the ulna, the radius, or both and have more distal extension of muscle fibers.

Table 1 Extrinsic Extensor Tendons

Compartment

Muscle

Abbreviation

Comment

1

Abductor pollicis longus

Extensor pollicis brevis

APL

EPB

Compartment is more palmar than others.

2

Extensor carpi radialis longus

Extensor carpi radialis brevis

ECRL

ECRB

Two wrist extensors

3

Extensor pollicis longus

EPL

Third compartment tendon goes to the thumb.

4

Extensor digitorum communis

Extensor indicis proprius

EDC

EIP

Four EDC tendons and “fore”finger tendon

5

Extensor digiti quinti or extensor digiti minimi

EDQ or EDM

Fifth finger independent extensor tendon

6

Extensor carpi ulnaris

ECU

Most ulnar extensor tendon

The four extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendons originate from a common muscle belly and have progressively limited independence moving from the index to small fingers.

The fascia over the extensor tendons thickens at the wrist to form the extensor retinaculum, with vertical septa separating the six extensor compartments (see FIG 1B; Table 1).

Juncturae tendinum provide interconnections between the EDC tendons just proximal to the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints.

The EIP and extensor digiti minimi are ulnar and deep to the EDC in the hand and at the MCP joint. The EIP passes beneath the junctura tendinum between the index and long common extensors.

At the level of the wrist, the EIP is deep to the other extensors, with a more distally extending muscle belly, making it easy to identify.

There can be considerable variability of the extensor tendons on the dorsum of the hand, with less than 50% of people having a separate EDC tendon to the small finger.21 Duplicated and interconnected tendons are common.12

The sagittal band holds the extensor tendon centered over the metacarpal head at the MCP joint and, through its connection to the volar plate, extends the joint.

Intrinsic extensors (FIG 1C)

Intrinsic extensors originate in the hand and include the four dorsal interossei, three palmar interossei, and four lumbricals. The thenar and hypothenar muscles also contribute to interphalangeal extension and MCP flexion.

The intrinsic tendons join to form the conjoined lateral bands volar to the axis of the MCP joint and continue dorsal to the axis of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints.21 This allows them to simultaneously flex the MCP joint and extend the PIP and DIP joints.

The palmar interossei insert on the lateral bands and sometimes to the proximal phalangeal bases—ulnar at the index finger and radial at the ring and small fingers.12

The dorsal interossei also attach to the lateral bands and proximal phalangeal bases—radial on the index finger, ulnar on the ring finger, and to both sides on the long finger.12

The lumbrical muscles originate on the radial side of the deep flexor tendons and insert into the radial conjoined lateral bands, serving as powerful MCP flexors.

Small finger abduction is via the abductor digiti minimi.

PATHOGENESIS

Zone I

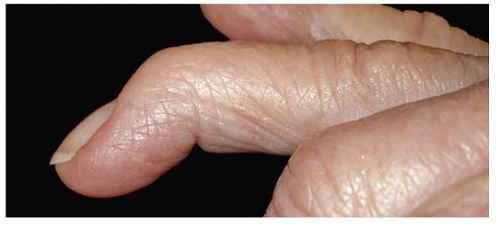

Disruption of the extensor tendon over the DIP joint will result in a terminal extensor lag after an open or closed injury (FIG 2).

Sudden forced flexion of the extended DIP joint can lead to an avulsion of the tendon from its insertion on the distal phalanx (mallet finger), possibly with an associated distal phalanx fracture. Large bony fragments may be associated with palmar subluxation of the DIP joint.

The long, ring, and small fingers are most frequently involved, although closed mallet injuries can also be seen in the index finger and thumb.2

Zone II

Laceration over the middle phalanx can give the clinical appearance of a zone I injury.

Injury to the periosteum and middle phalanx often lead to increased swelling, extensor tendon adherence, and DIP stiffness.

Zone III

Disruption of the central slip at the PIP joint may occur as a closed rupture (with or without an associated bone injury) or as an open injury, sometimes associated with traumatic arthrotomy.

Central slip avulsions are seen with volar PIP joint dislocations.

Early closed injuries may present with swelling, pain, and little extension loss but can progress to a boutonnière deformity (flexion of PIP and hyperextension of the DIP joint) as the lateral bands migrate palmarly and become flexors of

the PIP joint in the weeks after injury.21 Close follow-up and PIP extension splinting is warranted for suspicious injuries.

Zone IV

Injuries occur over the proximal phalanx and typically involve only a portion of the extensor mechanism but may involve the entire central slip.

Some portion of the extensor mechanism usually remains intact, making examination more difficult. With a complete central slip laceration, PIP extension may be maintained (through the lateral bands) initially, although a boutonnière deformity may develop later.

A complete central slip injury will often be associated with pain or weakness with resisted PIP extension (especially from an initially flexed position). As discussed earlier, close follow-up is warranted for suspicious injuries.

Zone V

Tendon injury occurs over the MCP joint.

There may be an open laceration of the extrinsic extensor, often related to a “fight bite,” or a closed injury to the sagittal band with extensor tendon subluxation.

Closed sagittal band injuries often result in ulnar subluxation of the extensor tendon.

Lacerations at this level should be assumed to extend into the MCP joint.

Zone VI

Disruption of extensor tendon is over the dorsum of the hand.

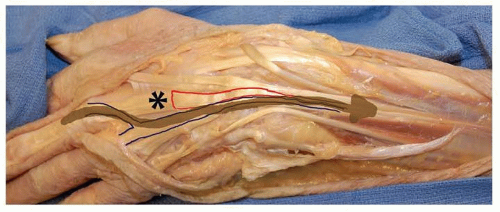

Single tendon and partial tendon lacerations may be difficult to identify due to maintenance of some digital extension through an intact junctura tendinum and EDC tendon from an adjacent digit (see FIG 3).

Zone VII

Lacerations occur over the wrist and through the extensor retinaculum.

Chronic disruptions can be seen in this zone following traumatic distal radius fractures or from prominent hardware after volar or dorsal fixation.

Zone VIII

Pathology is located in the forearm at the musculotendinous junction or muscle belly.

It may be difficult to detect concurrent posterior interosseous nerve injury in the presence of proximal extensor muscle lacerations.

Thumb

The terminal extensor tendon is thicker than in other digits—mallet injury is rare.

Tendon lacerations at, and distal to, the MCP joint are not associated with retraction of tendon ends, and primary repair is straightforward. Lacerations proximal to the MCP joint are associated with EPL retraction (often to the wrist) and require more timely repair.

NATURAL HISTORY

Untreated complete tendon lacerations at and distal to zone V will lead to persistent (and sometimes progressively worsening) digital deformity, often with continued pain and development of a flexion contracture.

Untreated terminal tendon injuries may lead to a swan-neck deformity due to proximal retraction of the digital extensor mechanism and increased extension force at the PIP joint.

Delayed treatment of central slip injuries may lead to boutonnière deformity and PIP flexion contracture as the lateral bands migrate palmarly, flexing the PIP joint and hyperextending the DIP joint.

Untreated tendon lacerations proximal to zone V will heal in lengthened fashion with pseudotendon formation. There may be a persistent extensor lag, weakness, or pain. Gradual loss of muscle length and elasticity (sometimes within as little as a week or two) can make delayed primary repair more difficult.

EPL tendon lacerations proximal to the MCP joint may be difficult to primarily repair as little as 2 weeks after the injury, requiring tendon grafting or EIP transfer.

Partial tendon lacerations involving less than 50% of the tendon width, longitudinal lacerations, and single lateral band lacerations will generally function well without repair.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Assessment and documentation of skin and soft tissue injury is important to aid in planning for débridement and extension of the skin incision for exposure and in determining the need for soft tissue coverage.

A complete neurologic and tendon examination is critical to rule out concurrent or remote injury that will alter treatment or outcome.

The EIP and EDQ are examined by testing independent index and small finger MCP joint extension.

The extrinsic extensor tendons are examined with the wrist in neutral, testing MCP extension against resistance. (Isolated PIP extension can be performed by the intrinsic muscles via intact lateral bands even in the presence of complete extrinsic extensor tendon lacerations.)

Examination of the digits may identify extensor lag, weakness, or pain with resistance to extension at the PIP or DIP joints.

The resting posture of the hand and absence of a tenodesis effect (MCP extension with passive wrist flexion) can also suggest an extensor tendon injury.

The Elson test can be used to diagnose a central slip injury.6 With loss of the central slip, lateral bands can migrate proximally to allow DIP extension with PIP flexion. Patients demonstrate a rigid DIP with attempted PIP extension from a flexed position with this test.

Active and passive range of motion and strength are assessed. Active motion loss helps determine tendon deficits, whereas loss of passive motion may be pain-related or represent remote injury or arthritis. Lacerations proximal to the juncturae tendinum may have nearly full motion but with weakness on strength testing and a small extensor lag (FIG 3).

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs are necessary to evaluate for any fractures, foreign bodies, preexisting injury, or arthritis that may alter treatment or affect the final result.

Ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is occasionally useful for suspected radiolucent foreign bodies. Although both studies can be used to more fully evaluate tendon injuries, treatment decisions are usually based on history and physical examination. Ultrasound may offer some value in diagnosis of lacerations of the central slip.24

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Radial or posterior interosseous nerve injury

Extensor tendon subluxation at the MCP joint

Chronic PIP flexion contracture and “pseudoboutonnière” deformity (no DIP hyperextension)

Physiologic swan-neck deformity or DIP joint osteoarthritis with apparent mallet deformity

Underlying joint deformity and arthrosis

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Disruption of the terminal extensor tendon (mallet finger)

Treatment consists of full-time static DIP splinting for 6 to 8 weeks, followed by an additional 6 weeks of protective splinting at night and during high-risk activities.

Patients must be counseled as to the importance of maintaining full DIP extension, even during splint changes.

A dorsal splint (FIG 4A) can allow the patient nearly full use and sensibility of the digit, although palmar or thermoplastic splints can be used in some cases (provided that full DIP extension can be ensured). A good fit without excessive DIP hyperextension (which can cause skin injury) is critical.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree