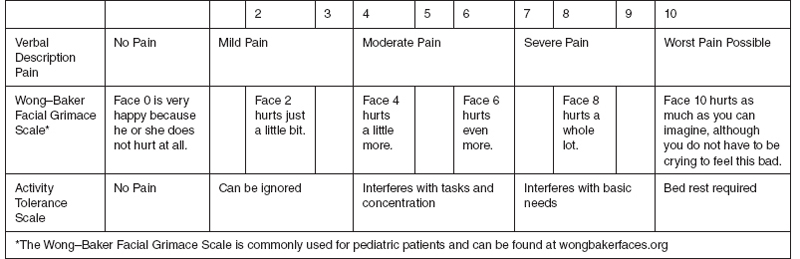

20 REHABILITATION OF CHRONIC PAIN AND CONVERSION DISORDERS Marisa A. Wiktor and Stacy J. B. Peterson (A. Chronic Pain) Michelle Miller (B. Conversion Disorders) Chronic pain and conversion disorders continue to be a diagnostic and treatment challenge for many physicians. They both require a creative, multidisciplinary approach for optimal outcomes. This chapter will summarize the current opinions, diagnostic strategies, and treatment protocols regarding these two conditions. A. CHRONIC PAIN UNDERSTANDING PAIN Historically, pain was considered a symptom of a disease and if the underlying cause were cured it would no longer exist. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (1). As our knowledge about pain continues to expand, there is evidence that chronic pain may cause more long-term harm than the initial disease or injury (2). Chronic pain is further defined as persistent and recurrent; it is a significant problem in the pediatric population estimated to affect 20% to 35% of children under the age of 18 around the world (3). Chronic pain can cause significant disruption in many facets of the patient’s life. It is not uncommon to observe in the pediatric population that suffers from chronic pain to be avoidant of school and social activities and demonstrate symptoms of clinical depression (4). The system that controls pain is complex and involves both ascending and descending pathways. A change in the pain conducting system occurs after tissue injury. Chronic pain may be due to neurons being pushed to their limits. Nociceptors that once only responded to noxious stimuli begin to fire in response to nonpainful stimuli causing receptors to evoke activity in the nociceptive system that is then interpreted as pain or central sensitization (2,5). Pain may be upregulated in order to receive immediate attention and withdraw from a stimulus or downregulated during a “fight or flight” response. Pain is necessary, as it allows us to process a potentially harmful situation and withdraw from or investigate the source to prevent further injury. Pain is one of the most common reasons that people seek medical attention. Inadequately controlled pain may result in unnecessary suffering resulting in compromised care of the underlying disease and lead to depression (6). Caregivers of children who do not feel pain or have “congenital insensitivity to pain,” need to be consistently vigilant to maintain a safe environment for their young (7). However, not all circumstances are preventable and these children may suffer severe injuries from painful events such as biting their tongue or burning their mouth with a hot beverage. Fortunately, this is an uncommon condition. Not all insensitivities to pain are congenital and some can be developed over time, for example, diabetic peripheral neuropathies or other peripheral nerve disorders/injuries. BRIEF HISTORY There was a time when many health professionals believed that babies could not perceive pain and their response was reflexive with little if any emotional ties. It was theorized that the nervous system of babies is underdeveloped at birth and their ability to experience pain was altered (8,9). During the 1980s in the United States, pediatric pain became a topic of focus after infant Jeffrey Lawson underwent surgical correction of a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) with only pancuronium bromide (neuromuscular blocker) and no analgesia, causing his mother to go to the press. After Jeffrey Lawson’s story made national headlines, pain control for even the youngest of patients became a priority. PREVENTION OF CHRONIC PAIN Treating pain acutely may be the best way of preventing chronic pain. Studies of male infants undergoing circumcision displayed an altered, intensified reaction to vaccination at 4 to 6 months compared to male infants who did not undergo circumcision (10). Long-term effects on the memory with subsequent painful experiences in neonates are unknown; however, memory is thought to play an important role in later pain events. Early exposure to painful stimuli may have long-lasting effects on perception and response to pain (11,12). PAIN SCALES Commonly, pain is accepted as the “fifth vital sign”; scoring systems for pain have become the expectation of patients and families and now are used as a benchmark by hospital accrediting bodies to improve the quality of care that patients receive on a daily basis (2). Despite their utility, pain intensity scores are inherently an oversimplification as they disregard elements such as the location, quality, and the emotional experience of pain (13). Currently, many pain assessment tools are available for evaluation of neonates, infants, children, and adults. Unfortunately, the majority of these scales require self-report as the primary means of assessment. Common self-report scales that are used include: the numerical rating scales (NRS), Visual Analog Scales (VAS), and Wong–Baker FACES Scale (Figure 20A.1). Observational scales for the developing child include: Faces, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability Scale (FLACC) (14) and the Child Facial Coding System. Other assessment tools that may be used for children include: Échelle Douleur Enfant San Salvador (DESS), the Pediatric Pain Profile, the Non-Communicating Children’s Pain Checklist (NCCPC), and the Pain Indicator for Communicatively Impaired Children (15–17). Providers should be aware of the many available pain scoring resources and should make their assessment with the most appropriate scoring systems given the patient’s age, intellectual ability, and experience. As previously mentioned, pain is complex and incorporates both sensory and emotional experience. Therefore, further research and validation of these tools are necessary, as they do not fully encompass the pain experience. CHRONIC PAIN IN THE DEVELOPMENTALLY DELAYED Evaluating the level of pain a developmentally delayed child is experiencing can be challenging in both the acute and chronic setting. Unfortunately, the term developmentally delayed tends to group many different intellectual and developmental disabilities into one category despite the possibility that characteristics of each condition may differ. Commonly, developmentally delayed children have multiple comorbidities that increase their exposure to health care providers and the likelihood of undergoing painful procedures. Many patients will not be able to verbally express their perception and experience thus leading the health care provider to make inferences of the level of pain and proper treatment modalities. Also, many impaired patients may express pain differently than those without limitations. In fact, some may lack expression completely or have a unique way expressing discomfort (18,19). FIGURE 20A.1 Wong–Baker FACES scale example. Source: Adapted from Perret D, Chang E, Hata J, et al. The Pain Center Manual. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing LLC; 2014: 163. A multidisciplinary approach that includes the patient’s primary care provider and other specialists who are working closely with the patient can prove to be beneficial to accomplish a common goal. It is important to involve the patient’s caregivers to gain insight into what they believe the patient may or may not be going through, but even then, requires significant inference. The overall goal of treatment should be directed toward quality of life improvement. NEUROPATHIC PAIN IN CHILDREN Neuropathic pain in children is well documented with an incidence reported to be around 6% (23). While there are some disease processes and causes of neuropathic pain that adults and children share, the picture of neuropathic pain in children is different. Many common causes of neuropathic pain in adults such as diabetes and trigeminal neuralgia are rare in childhood. Disease processes that are common in both include complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), which will be discussed later, and phantom limb pain. There are multiple known causes of neuropathic pain in children (Table 20A.1) in addition to these, such as Fabry’s disease, HIV, and cancer to name a few. Children more frequently, although still rarely, may have neuropathies due to metabolic and toxic causes such as heavy metal positioning or due to neurodegenerative or mitochondrial disorders. Of these, CRPS is likely the most recognized. TABLE 20A.1 CAUSES OF NEUROPATHIC PAIN IN CHILDREN Cancer 1° Nervous system tumor, tumor invasion of nerve, chemotherapeutic and radiation therapy, surgery Genetic Erythromelalgia, Fabry’s disease Infectious HIV, Herpes zoster Neurologic Multiple sclerosis, Guillain–Barré, CIDP Toxic Mercury, lead Trauma Direct nerve injury, phantom limb, CRPS Abbreviations: CIDP, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy; CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome. PHANTOM LIMB PAIN Children may undergo traumatic or iatrogenic amputation just as their adult counterparts. Children who have undergone surgical amputation of limbs have up to a 40% incidence of phantom limb pain (24). In the pediatric population, it is rarely associated with complications of diabetes of vascular disease, as these disease processes have not been long-standing to lead to amputation. Phantom pain can also occur in children with congenitally missing limbs; however, they are much less likely to experience pain compared to children who lose their limbs later in life (25,26). Phantom limb pain is children has been described as sharp, stabbing, piercing, squeezing and can lead to significant disability and affect functionality (25). There are several factors that predispose children to phantom limb pain including older age at the time of amputation, concomitant use of chemotherapy, and preoperative pain. Similar to phantom limb pain is brachial plexus injury. POSTOPERATIVE AND TRAUMA-RELATED PAIN The incidence of neuropathic pain in children following surgery is not clear, but is well reported. Common causes of persistent postoperative pain in children are post-thoracotomy pain as well as pain following various orthopedic procedures especially those associated with fracture. CANCER-RELATED NEUROPATHIC PAIN The incidence of neuropathic pain in children with cancer is unknown. However, it is known that neuropathic pain in children with cancer can be difficult to treat just as in their adult counterparts. A significant number of children with primary nervous system tumors report neuropathic pain. In addition, chemotherapy is a major cause of neuropathic pain in cancer patients, adult and children alike. Common chemotherapeutics that result in peripheral neuropathy are platinum agents such as cisplatin, and vinca alkaloids such as vincristine and vinblastine. FABRY’S DISEASE While Fabry’s disease is overall an uncommon cause of neuropathic pain, it merits mention, given it is a disease in which pain is often the presenting symptom and the age of presentation is in the first decade (25,27). Pain is initially intermittent but will generally become constant over time. Fabry’s disease is an X-linked recessive disease that leads to accumulation of glycolipids in multiple organs including the central nervous system (CNS). Pain incidence in this disease is quite high with up to 70% of affected males reporting pain (27). Furthermore, treatment of Fabry’s disease with enzyme replacement will lead to a decrease in pain scores although it does not decrease the incidence of pain (25). MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS (MS) It is common to find adults with MS-related pain. Of those with MS, approximately 5% will have their first symptoms prior to the age of 16 (25). There are multiple types of pain children with MS may experience including neuropathic pain. They, as their adult counterparts, may suffer from trigeminal neuralgia. POSTHERPETIC NEURALGIA (PHN) Although the herpes zoster infection or “shingles” is mostly known in adults, children too can experience PHN. While the incidence of herpes zoster in children does not reach that of adults, immunocompromised children can develop this infection and may go on to develop PHN. The incidence of herpes zoster is particularly prevalent in children undergoing treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (25). RADICULOPATHY Although seen less frequently in children than the adult population, children can present with radicular pain secondary to herniated discs. Children with vertebral anomalies such as pars defect, transitional or sixth vertebrae can be prone to further injury just as the adult population. In addition, children can suffer traumatic fracture of vertebrae or traumatic spondylolysis, which we have seen in contact sport injuries. TREATMENT OF NEUROPATHIC PAIN IN CHILDREN As in adults, neuropathic pain in children can be difficult to treat. Tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin, and pregabalin have the most frequent use in children. There are also reports of use of intravenous (IV) and intrathecal ketamine as well as topical treatments including lidocaine and capsaicin cream. In addition to common pharmacologic management, it is also important to remember that sometimes treatment of the underlying disease can lead to improved neuropathic pain. As is discussed in the following, pediatric pain is best treated within the context of the biopsychosocial model with the best responses seen with a multimodal approach to pain. Although less commonly performed in children than in adults, procedural interventions may be warranted. Procedures such as epidural steroid injections or spinal cord stimulation may be considered in the treatment of children; however, such interventions do not have the same supporting evidence that is present for adults. COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME (CRPS) CRPS, formerly known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, is well described in pediatric literature. Diagnostic criteria for CRPS can be defined by methods typically used to assess adult patients utilizing either The Budapest Criteria or the IASP Criteria most frequently. There are two defined types of CRPS: CRPS-1, where there is no defined nerve injury, and CRPS-2, which can be traced to a direct nerve injury (28). The disease can be debilitating, commonly characterized by allodynia, hyperalgesia, and burning pain (29). Children with CRPS are prone to significant emotional distress, school absenteeism, and decreased social interaction. There are some notable differences seen in children compared to the disease in adults. The first is a large gender gap with a female-to-male ratio between 3:1 and 6:1 (30). Also found in children is a large preference of the disease for the lower extremity (31). In addition, the long-term prognosis for children with CRPS is more favorable in comparison to their adult counterparts. Specifically, greater than 90% of children can achieve remission of the disease and this is almost always accomplished with physical therapy (PT), desensitization, mirror visual feedback, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) alone (26,32,33). It is now better understood that CRPS is not only a peripheral problem but strongly involves the neocortex, hence the role of multidisciplinary treatment (34). Children with CRPS respond best to noninvasive interdisciplinary programs with a focus on PT. Children tend to do well without any intervention apart from those used to facilitate PT in the early rehabilitation period. Desensitization therapy with continued use and mobilization of the limb is the mainstay of PT. Psychological therapy is also a cornerstone in the treatment of CRPS in children. Multiple models exist for accomplishing aggressive PT and behavioral therapy including inpatient models, day hospital treatment programs, and outpatient programs (35). Mainstay medication therapy used in children with CRPS mirrors those used in adults, which includes antidepressants, antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), as well as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and tramadol. Opioids are of limited benefit and are best avoided. Although the basis of treatment is nonintervention, a small percentage of children will fail noninvasive therapy or will at some point in their treatment undergo interventional pain management. Various types of intervention such as peripheral nerve blockade, lumbar sympathetic nerve blockage, epidural infusion, and spinal cord stimulation are reported in children (32,36). However, the majority of children will recover without such interventions and mainstream therapy remains focused on PT and CBT with positive outcomes. MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN IN CHILDREN Musculoskeletal pain is a common complaint in older children and adolescents with the most common complaint being low back pain (37). It is important to assess for possible underlying causes when first evaluating children with such complaints. A thorough exam can lead to the discovery of a hypermobility syndrome, which can be assessed with the Beighton scoring system, or early symptoms of an underlying rheumatologic disorder may be revealed. Children with musculoskeletal pain are prone to becoming adults with chronic pain. The basis of pain in children is often multifactorial in nature with psychosocial and lifestyle factors in addition to physiologic causes (37). There is a strong prevalence for musculoskeletal pain for adolescent females (38). Variable evidence exists to support the idea that having examples of chronic pain, such as a parent with chronic back pain, predisposes children to pain. The mainstay of treatment of musculoskeletal pain is best accomplished with multidisciplinary treatment consisting of CBT, PT, and pharmacotherapy. Appropriate pharmacotherapy for musculoskeletal pain in children is with the use of NSAIDs with possible role adjuvants such as antidepressants, AEDs, or medications such as tramadol. Of key importance in the use of these therapies is a focus on function and improved school attendance. If functionality is not achieved, adolescents with chronic pain are almost ensured to become adults with chronic pain. PEDIATRIC FIBROMYALGIA Fibromyalgia, also referred to as pain amplification syndrome, follows a similar yet distinct pattern in children compared with adults and requires specialized knowledge on the part of practitioners. Currently the diagnosis is based on clinical parameters; however, there is a potential autoimmune mechanism that is being considered as a contributing factor of childhood fibromyalgia (39). The major difference when comparing adult fibromyalgia to juvenile fibromyalgia is that children may have a better prognosis; specifically, they may outgrow the condition. Fibromyalgia is characterized as persistent diffuse pain, fatigue, poor sleep, and the presence of tender points on physical exam (40). Standard diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia in children have yet to be determined. Previous diagnostic criteria for adults included specific tender points; however, in 2010 The American College of Rheumatology revised the criteria, which are now generalized to widespread pain with associated symptomology (41). There are a limited number of studies on juvenile fibromyalgia and most treatment strategies stem from adult research. Treatment for fibromyalgia should focus primarily on nonpharmacologic therapies and utilizing pharmacologic therapies only if deemed appropriate by the treating practitioner(s). A multidisciplinary approach including medical management, psychotherapy with a focus on CBT, and physical/occupational therapy has proven beneficial. There is evidence that coping skills training can improve overall functioning in pediatric patients (42). The patients and their families should be educated on self-management strategies that focus on quality sleep, stress reduction, and exercise (43). INTERDISCIPLINARY CARE IN CHILDREN It is our belief that the treatment of children with pain is best accomplished with an interdisciplinary approach. Children and adolescents who present for evaluation of recurrent or chronic pain often exhibit functional disability just as their adult counterparts. In children this manifests by school avoidance, and decreased school attendance in addition to decreased physical activity and social interaction. Just as in adults, children too are prone to alteration of sleep patterns and appetite changes. While children can have specific diagnoses that cause pain, in many children there is often a lack of a discernible physical cause. Parents along with their children may have seen several providers by the time they arrive at a pediatric center. Often, at these major centers the focus becomes on treating pain in the setting of family, social, and school environments (35). Various models exist for interdisciplinary treatment of pain in children from strictly intermittent outpatient therapy, inpatient therapy, or intensive outpatient rehabilitation programs. Components of an interdisciplinary team often include PT, occupational therapy, medication management, psychology, psychiatry, and sometimes alternative therapies such as acupuncture. CBT is a cornerstone in treatment with a focus on teaching children how to self-regulate their pain by various techniques such as progressive muscle relaxation, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, and biofeedback (44). These all serve to improve function as well as decrease the fear associated with pain, giving children a sense of control. Use of interdisciplinary programs not only leads to decreased pain scores in children but also leads to improved school attendance (45–47). Other benefits include less medication use, reports of better social and emotional functioning, decreased catastrophizing, and decreased health care utilization (44). There is also recent data to suggest that intensive inpatient therapy improves function and pain more so than intermittent outpatient therapy (47). This is not to say that this is always the ideal treatment path, as many factors must be evaluated including severity of pain, parental support, functional disability, and school attendance. Given that these programs are limited, they should be reserved for those children with severe impairment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree