Chapter 15 Qigong

Initial Examination

Initial Examination

Client Goals: To eliminate back pain, increase activity level, and reduce her situational anxiety

Medications: Inderal, Coumadin, Lipitor, Xanax

Plan of Care

Plan of Care

Penelope attended six physical therapy sessions, which included (1) manual therapy to gently mobilize the thoracic spine to increase extension and address limited scapular mobility and myofascial dysfunction; (2) therapeutic exercise to strengthen the quadriceps, hamstrings, dorsiflexors, gluteus medius, abdominals, and short neck flexors; and (3) neuromuscular reeducation to facilitate diaphragmatic respiration, correct posture, and relaxation.

INVESTIGATING THE LITERATURE

Preliminary Reading

Qigong (pronounced chee-gung and also known as chi kung or chi gung) is one of the five pillars of traditional Chinese medicine along with herbology, nutrition, acupuncture, and manual therapy. This tradition is based on the concept of qi. The word qi usually is translated as “vital energy” or “breath” and is closely related, if not identical, to the yogic concept of “prana,” the Greek “pneuma,” the Hebrew “ruach,” the Native American “great spirit,” and the Judeo-Christian “breath of life.” This concept of vital energy is multifaceted and pervades traditional Chinese culture, including medicine, martial arts (wushu), and environmental design and placement (feng shui). When qi is sufficient and flows harmoniously in the mind-body, respiratory, cardiovascular, orthopedic, metabolic, and emotional health is optimal. Indeed, traditional Chinese medicine, unlike allopathic Western medicine, does not segregate psychological problems from physiological in evaluation and treatment, because both are manifestations of disordered qi flow (see Chapter 4).1 Correct biomechanical function allows qi to flow properly and that qi flow, in turn, allows ideal body mechanics and posture. Meanwhile, skeptics criticize the concept of qi as a worthless construct consistent with magical thinking.2 This skepticism is supported by the plethora of ways that the word qi is used, which makes it a hard concept for the Western mind to accept.

The first written record of qigong, defined as the science of vital energy accumulation, balance, and circulation, dates back to the Zhou dynasty, which ruled China from 1122 to 934 bc. Written during this era, the classic Tao Te Ching refers to breathing techniques that “concentrate Qi and achieve softness.” Over centuries of development, emperors, philosophers, scholars, clergy, martial artists, and doctors have contributed to the broad field of knowledge encompassed by the term qigong. Yoga practices from India and Tibetan practices were gradually cross-pollinated with qigong indigenous to China.3

Qigong, true to its substantially Taoist heritage, resists the scientific and scholarly impulse to reduce it to neatly defined categories. It can be categorized as an energy-based system, as a mind-body approach, or more accurately as belonging to both categories. In the same way, it is impossible to break qigong into mutually exclusive subcategories. However, several ways do exist to group similar practices together to help analyze the field.4,5

A third way to classify qigong is under the heading Nei Dan or Wai Dan.4 In Nei Dan (internal elixir), vital energy is gathered in the dantien (abdominal area) via breathing practices, movement, and mental focus and then lead by the mind to other parts of the body, especially the extremities. In Wai Dan, qi is drawn to the extremities and flow is stimulated by mental focus and muscular activity. When the qi flow is sufficient, it is thought to overflow into the rest of the meridian system to invigorate qi flow in general.

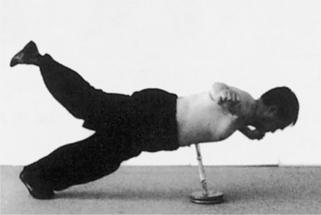

Although many forms of qigong exist, most, if not all, styles seek to cultivate a calm and quiet mind and the ability to release unnecessary muscular tension. They also teach correct posture, with the meaning of “correct” dependent on the style. Qigong also is meant to facilitate balance and stability and emphasizes, at least in initial training, breathing into the lower dantien. The dantien or sea of qi is located below (caudal and deep to) the navel and is meant to be the source of all movement. The lower dantien also is known as the hara in Japanese and as the navel chakra in Ayurvedic mind-body energetics. Broadly defined, qigong can encompass mental imagery, supine/seated/standing meditation, breath work, self-massage, intense shaolin-based practice,6 and exercises associated with internal martial arts, including tai chi chuan. Qigong styles that emphasize relaxation and equanimity, minimal to moderate exertion, and regulated breathing are thought to address stress-related problems, including mild to moderate hypertension. Qigong on the gentle end of the spectrum seems well suited for phase III and IV cardiac rehabilitation because of its apparent low risk of inducing myocardial ischemia or musculoskeletal injury. Because qigong healers may use a variety of practice approaches and employ a wide spectrum of techniques, some of which may be potentially dangerous (Figure 15-1) for Penelope,5–7 the therapist decides to contact the qigong instructor for a description of a typical qigong session before proceeding with a more specific search of the scientific literature. She obtains written permission from Penelope to discuss her issues with the qigong teacher and arranges a meeting with him.

Consulting with the Qigong Instructor

Sitting Meditation

The training would start with sitting meditation on a chair to begin the process of calming the mind and bringing moment-to-moment awareness of the body and breath (Figure 15-2). This instructor would encourage slow, continuous, diaphragmatic breathing through the nose. He would also teach her to be aware of her sitting posture and continuously adjust it according to qigong principles. By promoting physical relaxation and correct alignment, sitting meditation facilitates the circulation of blood and qi. Penelope would be instructed to focus on the breath and, when the mind wanders (as it is sure to do), gently return the focus to the sensation of respiration and spinal elongation. When the mind is calm and the posture is correct, qi flows more smoothly, evenly, and continuously.

Self-Massage

This part of the program would consist of self-applied massage to help relax the muscles, move lymph and blood, disperse qi stagnation, and stimulate smooth energy flow (Figure 15-3). Special attention would be given to certain acupuncture points, where qi flow can be manipulated easily, and the major channels through which qi flows.

Medical Qigong

This part of the qigong program would consist of exercises to help address the more specific qi stagnation and imbalance that Penelope’s history suggests is likely in her heart, kidney, and lung organ meridian system. Certain qigong movements, breathing, and mental awareness techniques promote the release, circulation, and balance of qi in these organs (Figure 15-4). The movements also apply gentle pressure and relax the organs and surrounding fascia, which provides a gentle massage that promotes circulation, increases respiratory efficiency, and balances function. All of these stretching and twisting movements would be performed gently and slowly. An example of these types of qigong movements would be forward and backward swing arms, in which she would swing her arms forward (shoulder flexion) while extending her thoracic spine and then swing her arms back (shoulder extension) while flexing her spine. Some of these qigong exercises also use sounds to help relax and nourish the organs. The heart sound (“Hawwwww”) is repeated subvocally as a mantra to help the heart be open and balanced.

Standing Meditation

The purpose of this practice is to gather and enhance circulation of qi while building strength and endurance, especially in the lower half of the body (Figure 15-5). This practice also teaches the practitioner to “root” herself to the ground to build stability and balance. This is a way to stimulate and regulate the function of the viscera, muscles, ligaments, and bones. Various processes, such as blood circulation, heart rate, breathing, and functioning of the nervous system, are thought to be optimized.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Reevaluation

Reevaluation Reevaluation

Reevaluation