3 PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT IN PEDIATRIC REHABILITATION Jamie L. Spohn and Jane A. Crowley Children’s needs within a rehabilitative setting are different from adults in that recovery of skills and return to baseline are not the end point. Rather, it is an evolution toward the continued development of ever-changing abilities in emotional, behavioral, and cognitive structures. The goal of any pediatric rehabilitation process is to foster the continuing work of childhood. This additional distinguishing dimension of pediatric rehabilitation relates to the central requisite of the pediatric population—development. There is a dual goal: rehabilitation to prior levels and capacity for the remaining development in that child’s or teen’s life. An important tool for establishing current levels, setting future goals, and tracking progress and/or changes over time is psychological assessment. The rehabilitation physician and the team will treat a wide array of medical conditions among their patients. Rehabilitation medicine departments will encounter requests for treatment for those with congenital disability, acquired disability from illness or injury, and chronic medical conditions. A recent estimate of the incidence of severe chronic illness seen in rehabilitation is more than 1 million children in the United States (1). These children, and those who survive catastrophic illness or injury, are a growing population due to medical advances that reduce mortality, covering the full age range from infancy to young adulthood. In acknowledging that normal development assumes an intact sensory, motor, and overall neurologic system for interaction with the environments of family and the larger world, the children and teens we work with do not have the standard equipment or interrelationships among the aforementioned skills. For example, a child’s motor disability can easily alter the basic emotional developmental tasks. The protraction of physical dependence that is a reality for a child with a congenital disability like spina bifida, at the very least, risks altering the psychological and developmental milestones of separation/individuation. Cognitive sequelae of that central nervous system (CNS) disorder can also result in academic, social, and adaptive behavior deficits. In these cases, standard developmental schema often does not apply (2). These developmental scripts do not apply not only because of deficits, but because there are unique tasks to be mastered with a disability. Functional use of a wheelchair, doing activities of daily living (ADLs) with one arm, self-catheterization, and visual competence with a field cut are but a few specific “milestones” our patients face. In the case of a traumatic injury, the disruption of a normal life as well as typical developmental progress and engagement in the world, is an emotional maelstrom for the patient and his or her family (3). It is possible that many problematic distortions in many aspects of the nurturing and individuating demands of competent development abound in children with disabling conditions (4). The barrage of medical technology and interventions is vast in variety and effectiveness. Yet, the psychological cost of these necessities can be astronomical. The challenges of hospitalization, a disruption of familiar routine, the therapy demands of the rehabilitation structure, absence of parents, and intrusive or painful medical procedures are additional tasks against which to hinder the patient’s progress (5). In a broader context, there is prejudice against those with disability, and children must face the extra demands of bridging ignorance and misconceptions among their peers and anyone else they may encounter. In line with the centrality of development, the objects of assessment constitute a “moving target.” Environmental demands change, as does the child’s or teen’s abilities to meet them. At school age, the child must now function competently in the ever-increasing demands for independence reflected in the school setting. Furthermore, the medical condition can itself change over a child’s development, causing a need for constant adaption. A disease process can progress (eg, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis), or increasing body size can change the nature of mobility (eg, spina bifida), and prior function can be lost, requiring significant adjustment on the part of the child or teen, as well as their parents or guardians. The task is to have these experiences remain challenges to development and not become barriers. This argues for continued monitoring throughout a child’s development as a vital factor and the importance of psychological assessment as a vital part of that monitoring to be utilized throughout the pediatric course of a patient’s life. This allows for continuous modifications as support throughout the individual’s developmental course. The relationship of family functioning to outcome in pediatric disability has been widely demonstrated (6,7). The challenge to a family is to walk an unfamiliar path, as few families have direct experience with childhood disability. The effects may be bidirectional (8), with the deficits from the medical condition interacting with parental features or the child’s status resulting in disrupted and possibly ineffective parenting approaches. Parents often must assume an additional role as case manager and advocate in the medical and educational systems. In addition, they have to “translate” their child’s issues to other family members at the nuclear and extended family levels. The family becomes a vital arena of intervention. The family is the first-order site of development and stimulation as well as a filter for the world at large. ADJUSTMENT VERSUS PSYCHIATRIC DIAGNOSIS It is important to recognize the distinction between psychiatric disturbance and adjustment problems as informed concepts in assessment for a pediatric rehabilitation population. Indeed, psychiatric disturbance is not common in children with chronic conditions, as some studies show that their functioning is better than children in the mental health clinic population. Taken together, however, children and teens seen in rehabilitation medicine settings do have a greater risk for adjustment problems (9). Their medical conditions act as life stressors not encountered by their healthy peers. To use psychiatric diagnoses in this population belies the reality of behavioral symptomatology that is indeed adaptive to the conditions and situations of a child’s medical condition. Though some behaviors may be unusual in the healthy child, they may be adaptive to this population (9). The concept of adjustment encompasses the variability that these patients encounter. It can express the unique trajectory that these children’s lives will take, and recognizes it as adaptive in that it is age-appropriate for those conditions and oriented ultimately toward healthy adult functioning. A large body of literature focuses on the adjustment of children with chronic physical conditions. This group was twice as likely to have adjustment problems as healthy children in a meta-analysis of 87 articles by Lavigne and Faier-Routman (9). Though the specific prevalence rates were higher among these children, only a minority showed maladjustment. Such children, then, are more vulnerable than those who are healthy. Newer assessment instruments have been developed that utilize the concept of quality of life (10) and will be discussed here in the section “Population-Specific Assessments.” With this approach, the nature of a child’s or teen’s adjustment and the reflection of the uncontrollable factors in his or her situation are captured for a wider rubric than the inadequate dichotomy of normal versus abnormal. However, the use of psychiatric diagnoses can be appropriate in both this population and those with neurodevelopmental disabilities. The latter group showed a rate six times that of the general population for significant emotional and behavioral problems (drawn from an outpatient clinic population) (11). The identified problems run the gamut, encompassing a breadth of both emotional and behavioral disorders, and are more likely to persist into adulthood. There is the primary impairment of the neurologic disorder and a secondary impairment of psychosocial support problems (4). With the disturbance in the brain being primary, these findings are not surprising. Other factors exist as well to either exacerbate or ameliorate the brain’s abnormality, but the overall picture is one of significant neurologic and psychological morbidity, with the source of disability either congenital or traumatic. The most common disabling injury of childhood, in fact, is traumatic brain injury (TBI; 12), which carries a substantial risk for long-term physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral difficulties (13). Expressed differently, incidence figures are such that by the tenth grade, 1 in 30 students would have had a TBI (across severity ranges of mild, moderate, or severe). This population will be a substantial part of a pediatric rehabilitation medicine practice. The causative link between cognitive and behavioral functioning represents the juncture of thinking and adaptive behavior that can be devastating to the ongoing development of a child survivor of an acquired injury (14). There is a particular danger in the misattribution that easily occurs. Behavioral deficits will likely be attributed to more common etiologies, as opposed to the organic brain disorder from the injury. With misattribution comes the inevitable inappropriate treatment. Cognitive limitations are not accounted for in treatment efforts, or the wrong premise (eg, antecedent versus contingent programming) used, and failure occurs or even exacerbation of the original problems. Awareness and consideration of the brain damage from an injury means assessment must encompass a wide focus, looking at emotional, behavioral, cognitive, personality, and adaptive domains. Neuropsychological testing is the centerpiece in these children and teens, representing a subtype of general psychological assessment that will be an important aspect of many rehabilitation cases. NATURE OF MEASUREMENT The essence of psychological assessment lies in the construction of the instruments used to explore various domains of adjustment, personality functioning, behavior, emotion, and cognition. This construction always has at its core the notion of standardization through its reference to a normative group, whose performance is characterized by a transformation of the raw score earned by an individual. Even the most skilled observer could not provide the richness of the information gleaned from a psychometrically sound instrument. Such a test allows for the comparison of that subject to the typical performance of his or her peers in a fair and objective way. The value of standardized assessment depends on some core concepts, elucidated in the following sections. It is standard for clinicians to rely on not only standardized instruments, but also behavioral observation and input from the child’s exterior world, including parental information as well as information from the child’s school. Conclusions are drawn when all sources of information have contributed. NORM-REFERENCED MEASUREMENT Norm-referenced tests are standardized on a clearly defined group, referred to as the normative group, and scaled so that each individual score reflects a rank within that group. The examinee’s performance is compared to the group, generally a sample that represents the child population of the United States. The comparison is carried out by converting the raw score into some relative measure. These are derived scores and indicate the standing of a patient relative to the normative sample by which the test was standardized. These scores also allow for comparison of the child’s performance on different tests. Stanines, standard scores, age- and grade-equivalent scores, and percentile ranks are the most common tests. A central concept in the expression of individual performance as compared to a norm group is the normal curve. The normal curve (Figure 3.1) is a bell-shaped curve. It represents the distribution of many psychological traits, with the greatest proportion at the “middle” of the curve, where it is the largest, and the abnormal levels—both below and above average—at the two “tails.” All derived scores have a distinct placement on the normal curve and are varying expressions of the location of an individual’s performance on that curve. Stanines are expressed as whole numbers from 1 to 9. The mean is 5, with a standard deviation of 2. Substandard performance would be judged with stanines in the range of 1 to 3 and above average at 7 to 9. In this transformation, the shape of the original distribution of raw scores is changed into the normal curve. Standard scores are generally the preferred derived scores (15). Their transformation of raw scores yields a mean for the normative group and a standard deviation. This places a given score across the normal curve, and the scores express the distance from the mean of that patient’s performance. T scores, z scores, and the well-known IQ of the Wechsler scales are all standard scores. Like all standard scores, the z score derives a constant mean and standard deviation across all age ranges The z score has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. It expresses below-normal performances with the minus sign and above average with the plus sign, with scores in a range of -3 to +3. These scores are often transformed into other standard scores to eliminate the positive and negative signs (see Figure 3.1). T scores and the IQ scores are drawn from the z score, with different numerical rubrics that eliminate the plus or minus sign associated with the z score. Multiplying by 10 and adding a constant of 50 yield a T score ranging from 20 to 80, with an average of 50. Another transformation occurs by multiplying the standard score by 15 and adding 100. This provides a range from 55 to 145, with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15 or 16, depending on the test used. This is the method that produces the Deviation IQ, the form of derived score used on the Wechsler intelligence batteries. The alternative to the Deviation IQ is the Ratio IQ, which is the ratio of mental age to chronological age multiplied by 100, used in the Stanford-Binet tests. FIGURE 3.1 The normal curve. Even more straightforward appeal exists for age- and grade-equivalent scores. These scores are obtained by discerning the average raw score performance on a test for children of a given age or grade level. These scores are often used when the child is given a test of academic ability. The individual patient’s score on that test is compared to that value. Grade equivalencies are expressed as tenths of a grade (eg, a grade equivalency of 4.1 represents the beginning of fourth grade). Despite their appeal, there are limitations with these forms of derived scores. First, a grade-equivalency value does not mean that a child is performing at that particular level within his or her own school, as the curricular expectations of the school might be different from the mean score established by the normative sample. Some actual age- or grade-equivalency values might not have been earned by any specific member of a normative sample, but instead are extrapolated or interpolated from other points of data. Furthermore, age or grade equivalencies may not be comparable across different tests. The meaning of a first grader who obtains a raw score similar to a third grader is not that the child is functioning as a third grader in that subject. He or she shares that score, but the assumption that the child in first grade has all the skills of a third grader is inappropriate. Similarly, a 12-year-old patient who achieves an age equivalency score of 8 years, 4 months seldom actually functioned on the test the way a typical 8-year-old child would, and certainly should not be treated like an 8-year-old for most issues in rehabilitation or academic programming. Finally, as is the case with percentiles, age- and grade-equivalents cannot be used in statistical tests, as there is an unequal distribution of scores. Both require conversion to another scale before they can be used in data analysis. RELIABILITY This concept of reliability refers to the ability of a test to yield stable (ie, reliable) results if readministered at different points in time. There needs to be a consistency and stability of test scores, and the nonsystematic variation reduced as much as possible. Psychometric theory holds that any score is composed of the measurement of the actual trait that a child possesses as well as an error score, which represents the variation or standard error of measurement. The reliability coefficient is the familiar statistic to express this property. It can vary from 0.00, indicating no reliability, to 1.00, indicating perfect reliability. High-reliability coefficients are considered particularly important for tests used for individual assessment. In the case of cognitive and special ability tests, a reliability coefficient of 0.80 or higher is required for sufficient stability to be a useful test. Reliability coefficients are calculated for a test across three conditions of reliability. One is test–retest reliability, meaning the capacity of the test to yield a similar score if given a second time to a child. Another is alternate-form reliability, where the child is tested with an alternate form of the test, measuring the same trait and in the same way as the initial testing. A third kind refers to internal stability in a test, where in the ideal test, item responses are compared to another item on the test to demonstrate the equivalence of items in measuring the construct in a replicable manner. Active judgments must be made in the choice of tests, with reliability coefficients reviewed in the process of test selection. VALIDITY Validity is another crucial component to consider in the construction and use of standardized measures. Validity is the extent to which a test actually measures what it intends to measure and affects the appropriateness with which inferences can be made based on the test results. Validity of a given test is expressed as the degree of correlation, with external criteria generally accepted as an indication of the trait or characteristic. Validity is discussed primarily in terms of content—whether test items represent the domain being measured as claimed—or criterion—the relationship between test scores and a particular criterion or outcome. The criterion may be concurrent, such as comparison of performance on neuropsychological test measures with neurophysiologic measures (eg, computed tomography, electroencephalography). Alternatively, the criterion may be predictive—the extent to which test measures relate in a predictive fashion to a future criterion (eg, school achievement). In the rehabilitation context, various events and contingencies may affect predictive validity. An appropriate determinant of predictive validity is the likelihood that the individual’s test performance reasonably reflects performance for a considerable period of time after the test administration. Acute disruption in physical or emotional functioning could certainly interfere with intellectual efficiency, leading to nonrepresentative, or failure to measure what it is intended to measure, results. In contrast, chronic conditions would be less likely to invalidate the child’s performance from a predictive standpoint because significant change in performance as a function of illness or impairment would not be expected over time. With therapeutic interventions, a patient’s performance could improve, so test results from prior to that would not be valid. The more time that passes between test administrations, the more likely extraneous factors can intervene and dilute prior predictive validity, making updated testing imperative for continued ability. Anxiety, motivation, rapport, physical and sensory handicaps, bilingualism, and educational deficiencies can all effect validity (15). For an inpatient population, the effects of acute medical conditions (eg, pain, the stress of hospitalization, medical interventions themselves, fatigue) can also affect validity. Wendlend and colleagues (16) noted that in a study of cognitive status postpoliomyelitis, the deficit seen could well have been due to the effect of hospitalization as opposed to the disease. The understanding of acute effects of hospitalization on psychological testing makes it imperative to retest the child in order to have results to compare to as the child is released from the inpatient setting. Construct validity refers to the extent to which the test relates to relevant factors. Another important component of validity is ecological validity, which refers to the extent to which test scores predict actual functionality in real-world settings. Test scores are typically obtained under highly structured clinical testing situations, which include quiet conditions, few distractions, one-on-one guidance, explicit instructions, praise, redirection, and so on. These conditions do not represent typical everyday tasks or settings (17). This disconnect between the test setting and real life is especially relevant in children with brain-related illness or injury. These children, who have high rates of disordered executive functioning (eg, distraction control, organization, planning, self-monitoring, etc.) benefit disproportionately from the highly directive nature of clinical testing, and test scores may overestimate true functional capacity for everyday tasks (18). A test’s reliability affects validity in that a test must yield reproducible results to be valid. However, as detailed previously, validity requires additional elements. In the rehabilitation population, all of these issues have particular importance. Most tests are developed on a physically healthy population. Motor and sensory handicaps and neurologic impairment are not within the normative samples. Issues of validity predominate here, though with transitory factors as noted previously, reliability can be affected as well. Standardized procedures may have to be modified to ensure that a patient is engaged in the testing in a meaningful way. USES OF ASSESSMENT The use of psychological assessment aims to further the functioning and adjustment of children with a wide range of disabilities or chronic illnesses. These purposes encompass issues directly related to the medical and rehabilitation setting, but often have equal utility in educational planning. Unique to the field of pediatric rehabilitation is this necessity for interaction between what are arguably the two biggest public systems for children: medicine and education. Both have their productive and counterproductive forces and hold a vital place in the individual child’s or teen’s life. Furthermore, both can act to hinder or potentiate the salutary effect of the other. The needs and parameters of engagement with both is at the crux of the navigation of development for our patients, and psychological assessment contributes significantly to this process. Psychological testing is often associated solely with IQ testing. The IQ concept of intellectual development is too narrow for many of the applications in a pediatric rehabilitation setting. Instead, the broader notion of cognitive abilities, not merely intellectual abilities, is considered more important. Cognitive assessment covers testing the wide array of known components of the brain’s thinking, reasoning, and problem solving. Assessing these intake, processing, and output modalities of thinking, their individual elements or the combination of these skills is a vital factor in school or in medical rehabilitation. School is children’s work, and the interface with this system is critical, as it is the arena where many key adjustment and developmental issues are played out. Psychological adjustment—indeed, overall functioning—is closely tied to cognitive status. Coping with frustration, functioning within a group, and inhibiting and planning for long-term goals, are examples of processes vital to school that have cognitive capacity at their center. Within the schools, the psychological assessment performed has typically included only intellectual and academic achievement testing as prime components. Though that is changing in some settings, it is not yet common that cognitive processes are assessed within the school setting. For the populations common to a rehabilitation medicine practice, many conditions have brain involvement (eg, TBI). Their needs are clearly beyond the limitations of typical school testing capabilities. Eligibility for services within the special education system under the qualifying conditions of TBI (mandated by the federal government in 1998) cannot be done without consideration beyond IQ and achievement testing. Indeed, TBI as its own inclusion category was done to reflect the serious misunderstanding of the disorder when only evaluated by IQ and achievement testing alone. TBI evaluation lies in stark contrast to individuals with learning disabilities, which is typical what the school is able to piece together through the use of just intellectual and academic achievement testing. The intellectual assessment of children with spina bifida needs explication beyond IQ testing as well. Often, the component parts of the Full-Scale IQ score are so divergent in children with spina bifida and other brain conditions that it does not represent a true summary score, and thus must be interpreted on an individual subtest level, rather than merely looking at composite scores. To understand a child’s condition fully, further assessment of cognitive processes needs to be done. Pertinent abilities are attention, concentration, memory, and executive functions. In the wide array of conditions known to affect brain functioning there are primary and secondary effects. Primary effects are seen from brain tumors, seizure disorders, or cancer processes. Secondary, or “late” effects on cognitive processes are seen in the process of infectious disease or cancer treatment. It is necessary to evaluate a broader array of abilities rather than relying solely on IQ to understand the full spectrum of required cognitive skills for competent development. In order to promote the fuller understanding of medical conditions and their effects on cognitive functioning, the rehabilitation practitioner will often be consulted for more specialized assessment to capture the full nature of functioning within his or her patients. Input into the Individualized Educational Plan (IEP), which is the centerpiece of planning in the special education system, is essential in brain-based disorders to ensure full consideration of the medical condition, its own process, and its unique effect on brain functioning. The dynamic nature of recovery is notably absent from most students receiving special education services, but is often a primary part of the course in TBI, brain infectious processes, cancer, or strokes. Frequent reassessment, specific remediation or rehabilitative-focused services, or specialized support in school reentry, and transition are several of the unique concepts that are vital to sound educational planning in our population but are largely unknown to the traditional process of special education. This is the most critical juncture of school and medical factors in a pediatric rehabilitation process. As per Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, accommodations are often sought on either a long-term or transitory basis in rehabilitation medicine patient groups. These are efforts to “level the playing field” within the school setting in acknowledgement of disability that skews a student’s ability to benefit from the standard educational setting. These students do not require the breadth or type of actual intervention or service gained through special education classification and do not require special classification. Instead, these students need modifications in the system in order to demonstrate their capacities or adequately access the learning environment and mainstream curriculum. Results of psychological/neuropsychological evaluations can be useful in demonstrating such needs related to cognitive issues. For example, deficits in information processing speed can have a global effect on functioning within the group instructional environment of school. Accommodations such as reduction in homework, extended time for tests, quizzes, or assignments, or lecture notes, among others, can all be sought with the documentation provided by evaluation results. The issue of how long the accommodations are required can be answered by repeated testing. An example is in the case of a brain injury where recovery occurs and accommodations may no longer be necessary. It is of the utmost importance for the clinician to recognize and have a solid understanding of the role he or she can play in securing vital (but not necessarily typical) medical treatment for a patient. This includes speech and language or occupational therapy, cognitive remediation, or adjustment-focused cognitive behavioral work. The documentation of that need, based on the medical diagnosis or history, can be obtained much quicker and with the proper focus through the medical system in terms of both insurance coverage and proper treatment frequency and formulation. Obtaining assessment from a public school system can be a lengthy process. For rehabilitation patients, this can waste valuable time and, therefore, cannot meet the time frame needed for an acute recovery. A typical school psychological assessment could miss acute issues and be even less likely to detect weaknesses that could hamper development or skill acquisition distant from the injury or illness. Such evaluation needs the medical framework of rehabilitation psychology to be timely and pertinent. Furthermore, with a rehabilitation psychology perspective and knowledge, appropriate documentation emerges to secure services covered by medical insurance or from legal settlement funds, if such exists. Further, a broader range of knowledge exists within a rehabilitation setting related to access to other services, resources within the patient’s community, and specific school and classroom placement planning. Keeping the intervention within the medical perspective can make it more integrated with disease or injury sequelae and, therefore, more targeted and appropriate in terms of goals and treatment techniques. It can be seen that the assessment of a child’s or teen’s learning process is essential to both the school and medical setting. Memory processes, language abilities, planning, and capacity to inhibit are essential functional elements in either system. The preference of one modality over another, or the explication of memory functioning, can be of great use in school issues and in rehabilitation. The need to master specialized tasks, such as wheelchair skills or self-catheterization, can be enhanced when general learning styles of an individual patient can be discerned. This understanding of a patient’s cognition can inform educating the patient about his or her medical disorder, or the rationale about a medical procedure. The feelings of victimization that can evolve around a painful surgery and the subsequent effect on adjustment or even personality formation are secondary sources of potential morbidity in a child’s development. The child or teen senses that he or she was regarded enough in the consideration of procedures to be included in the decision and planning process. The experience of this and the skill to be a meaningful participant are vital long-term skills and are promulgated by knowing the proper way to present material in a way to ensure understanding. Decisions about a child’s ability to benefit from a specific treatment such as biofeedback, relaxation training, or the varieties of behavioral programming available are part of diagnostics that guide treatment. Change as the result of intervention can be quantified by assessment. However, change without overt intervention, but to chronicle the long-term outplay of a medical condition, is arguably the most common use of assessment in rehabilitation. The risk for long-term sequelae in TBI or from cancer processes and treatment is well known (13,19). The serial assessment of a patient, particularly through known critical developmental periods or illness interventions, is at the core of sound pediatric rehabilitation practice. A developmental lag becomes the object of treatment, whether to spur development or to teach compensatory strategies. As the physical process of a disease is monitored through traditional outpatient clinic visits, so is the status of cognitive/behavioral functioning in relation to the demand of one’s medical condition or to changing developmental expectations is equally important to monitor. Understanding the individual experience of a child or teen in relation to his or her body experience is another use of assessment. Understanding the experience, whether through a questionnaire about pain, assessment of specific mood states like depression or anxiety, or a general personality assessment of that patient, can be quite useful. Differential diagnosis can be important, as in the case of posttraumatic stress disorder, where cognitive symptoms of that disorder can be mistaken for the effects of a mild brain injury or concussion. In that circumstance, the deficits are due to the effects of the stress and not to the mechanical disruption of trauma. TYPES OF ASSESSMENTS The purpose of psychological assessment is to discern the status of an individual in relation to an appropriate peer group. Jerome Sattler discerns four pillars of child assessment as norm-referenced tests, interviews, observations, and informal assessment (15). This is a broader list than many referral sources would recognize, as typically “tests” are all that might be considered as psychological assessment or evaluation. However, a central tenet in psychology is that test scores or results cannot be interpreted in isolation. Information from naturalistic settings must be sought through the methods of interview, observations, and informal assessments, as enumerated by Sattler. In a discussion of cognitive testing, the issues of single tests versus batteries are an important consideration. Single tests are designed to tap a specific dimension of cognition, like verbal learning or visual–motor abilities. As useful as they are for more in-depth examination of a single construct, this strength is a source of limitation as well. Seldom is the question at hand to be answered by examining a single ability. Abilities are not the unitary concepts that evolve from theoretic models. The influence of other overarching cognitive abilities, such as attention or processing speed, is not addressed directly and is discernible only through observation. Normative samples for single tests can be restricted and not large enough or representative enough to draw firm conclusions as to standing within one’s peer group. Therefore, the use of a test battery is preferred. APPROACHES TO ASSESSMENT Historically, there are three approaches to assessment, especially neuropsychological assessment, that have been widely used. The first is called a fixed battery of tests. The best-known example of a test battery is the Wechsler batteries for intelligence assessment, comprising a number of subtests. These collections cover an array of abilities. The fixed battery is a predetermined set of subtests that are administered in a standard format to every patient. This same set of tests is administered regardless of the referral questions or set of symptoms that a patient presents with. The advantages of a fixed battery include a comprehensive view of the patient’s cognitive domains. They also provide the strongest basis for comparison of a patient’s performance across subtests, as norms are based on this arrangement of tests, given in the established order or both strengths (what a patient is able to do) and weaknesses. The use of a standardized format in fixed batteries is also highly useful for research purposes. Another advantage is when the evaluation results are questioned, such as in a court proceeding, where the examiner will be required to defend his or her evaluation findings. This approach is also beneficial for green practitioners who are not yet comfortable with choosing their own batteries. There are several disadvantages for the use of a fixed battery approach. One is that it is exceedingly time-consuming. Since all tests within the battery must be administered, the time it takes to do such is often a barrier to choosing this type of approach. The fixed battery approach requires the clinician to examine all areas, even those that appear intact. This results in an excessive collection of data that may have little or no use to the clinician. Another disadvantage is the lack of flexibility in different clinical situations. This makes it sensitive to detecting focal deficits, as opposed to diffuse deficits, which is often what a child presents with. A flexible battery is composed of a number of single tests, assembled with the patient’s referral question or known medical condition and/or symptoms in mind, with an eye to tapping tests most likely to explicate suspected deficits. Thus, the battery is individually tailored to each patient based upon a diagnostic question. Flexibility can allow for modification and possibly individualization of directions during the assessment (20). Lezak and colleagues (21) noted a survey of neuropsychologists where 70% responded that they use a flexible battery approach. They note the position that fixed batteries involve more testing than some patients need. Further, the flexible approach continues to increase in popularity, as health insurance corporations are continuing to restrict reimbursement for longer evaluations (22). Automated or computer use in testing has increased substantially since the 1980s. Prior to that, automated and later computerized administration and scoring of tests was quite limited. Initially, computerized testing of attention was developed (Connors Continuous Performance Test). More recently, computerized tests have been developed for concussion diagnosis and monitoring, in addition to research purposes. Such techniques offer repeatability, sensitivity to subtle cognitive changes, and ease of administration. Reliability, validity, and other considerations pertinent to general issues in more traditional so-called pen-and-paper tests are pertinent to this type of assessment as well. Computerized testing for concussion will be discussed in the Concussion chapter of this book (Chapter 12). Evaluation, then, is a robust and multifactorial process, not to be confined to a set of test scores or descriptions of test performance, but also to include natural setting, or qualitative observation, data. The norm-referenced placement of a patient has a role, but the assessment setting in and of itself imposes a high degree of structure. While this one-to-one administration is not replicated in real life, it is necessary for the standardization of administration and the reference to a normative sample, as described previously. This offers a “best case scenario” for the patient, which has implication when compared to “real-life” settings. Therefore, the addition of perspectives from natural settings of the home, school, and community is necessary, as is the consideration of the aspects of the medical condition. The interpretation of standardized tests must take these factors into account: issues about the course of a disease or injury recovery, the unique interface that the course of an illness or recovery has on the timetable of childhood development, and the actual length of the struggle with the medical condition. Some of these elements are captured in a good history taking and/or record review. Reserve factors concerning coping and response are also gathered in history but can additionally be tapped by standardized questionnaires, whose responses are sought from a variety of sources. These encompass figures from the major settings in a child’s life (ie, parents and teachers). The value of such instruments is that they can reference responses to those of a normative population such that the degree of divergence from standard development can be expressed. Some include consistency scales that add information about the nature of the responses given. CULTURE-SENSITIVE ASSESSMENT Culturally sensitive psychological assessment is often a challenging aspect of the testing process. Most measures have a culture bias in terms of content and validity, and normative data are seldom adequately representative of diverse groups. Not all examiners are sufficiently sensitive to the impact of cultural issues on children’s performance, and when interpreted without caution, results can be misleading. The assessment of English language learners, children who have reduced mastery of the English language because their parents’ primary language is not English, is particularly challenging. Use of interpreters or test translations carries limitations, such as lack of equivalent concepts in the two languages, minimal provision for dialectical variations, performance anxiety to having an “audience” present, and possible changes in the level of difficulty or meaning of translated words (15). Several “culture-fair” tests have been developed to reduce culture bias by limiting the amount of verbal exchange, using more abstract content that is less grounded in culture and language, and using more diverse groups during the norming process. This represents an important step in culturally sensitive assessments, and some of these tests are discussed in the following sections. However, there is no way to truly eliminate cultural bias from tests, and demographic data on normative groups must be carefully examined before assuming that it is any more representative of the specific patient than traditional tests. For example, many of the “culture-fair” tests are normed only on children in the United States. Their use for students with different backgrounds, such as children from refugee camps in Africa with little to no formal schooling, is clearly limited. Culture-sensitive assessments in pediatric populations are made even more complicated by the frequency of mild to severe motor impairment. Examiners assessing individuals with motoric impairment rely heavily on tests of verbal cognitive skills and try to reduce the number of tasks that require speeded or complex motor responses. Examiners assessing individuals from linguistically or culturally diverse backgrounds rely heavily on tests of nonverbal cognitive skills and try to reduce the verbal component. Examiners assessing individuals from linguistically diverse backgrounds with motor impairments are limited indeed in terms of valid options. Even in pediatric groups that do not have motor impairment, the higher frequency of discrepancies in functioning (significant strengths and weaknesses in a single individual, such as may be caused by damage to right versus left hemisphere or cortical versus subcortical areas) makes the traditional practice of assessing nonverbal skills and considering the results representative of general functioning highly questionable. School and community-based clinicians may not be aware of the complexity of issues involved and may provide scores without adequate caution regarding limitations. SPECIFIC INSTRUMENTS NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL EVALUATION Originally, the neuropsychological assessment was directed at diagnosing the presence, nature, and site of brain dysfunction. The focus has shifted from diagnosis to assessment of a child’s function to identify and implement effective management, rehabilitation, or remediation services. NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL BATTERIES As mentioned earlier, neuropsychological batteries have been developed to provide a comprehensive evaluation of cognitive abilities. The two most common in practice today are the downward extensions of the Halstead–Reitan Neuropsychological Battery and the NEPSY-II, developed specifically for children. The Halstead–Reitan Battery has been refined and redefined over the years since Ward Halstead’s original conceptualization in the 1940s to a larger series of tests to diagnose so-called brain damage for ages 14 and above (23), and subsequently the downward extension for ages 9 to 14, called the Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery for Older Children (HRNB-C). It takes approximately 4 to 6 hours to administer, and it uses subtests from the adult Halstead–Reitan Battery, with some modifications. The battery for children aged 5 to 8 is called the Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery and requires a similar time interval for administration. These batteries, in wide use earlier, are criticized for a number of pivotal problems. The first is on conceptual grounds, in that the battery was not developed for children, but for adults, and is perhaps reflected in the minimal assessment of memory, academics, and language, with no direct measure of attention. The psychometric properties are widely acknowledged to be quite poor, such that reliance on those alone for interpretation is inappropriate. Considerable clinical acumen is required to interpret findings. Dean concludes a review of the batteries saying, “The HRNB cannot be recommended for general clinical use without considerable training and familiarity with research on the battery (24).” Considering norms published in the interim, Lezak et al. (21) is more favorable to the HRNB in saying that what statistics it yields are misappropriated by “naïve clinicians,” implying the same point as Dean. The only neuropsychological battery ever developed specifically for children is the NEPSY-A Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment (25), with the newest version, the NEPSY-II (26), published in 2007. Both batteries are based on the diagnostic principles of the Russian neuropsychologist Alexander Luria. The original NEPSY had two forms and covered ages 3 to 4 and 5 to 12, with a core battery of 11 to 14 subtests represented to tap five functional domains: attention and executive functions, sensorimotor functions, language, visuospatial processing, and memory and learning functions. This original version was criticized for its content and psychometric properties (27). It is well standardized, and though some instability is noted in some subtests, this may indeed reflect the reality of the developmental status of the brain. The most recent version expands the age range to 16 years, extending one ostensible benefit of a battery that covers the childhood range, allowing for the ideal serial assessment. The content has also changed, with targeted groupings of subtests for various diagnoses, nonverbal elements, and new measures of executive functioning, memory, and learning, which reportedly solves some of its statistical problems. A functional domain in social perception has been added as well. ATTENTION, CONCENTRATION, AND INFORMATION PROCESSING The processes of attention, concentration, and information processing are often central concerns for any patient with a medical condition involving the brain (28). In many ways, they form the basis on which the other component processes occur. Overall performance on other tests looking at other domains of cognitive functioning is significantly impacted by attention and information processing. Attention has been conceptualized in a number of ways, generally relating to an organism’s receptivity to incoming stimuli. Most do regard the issues of automatic attention processes versus deliberate/voluntary as central dimensions. Other characteristics include sustained, purposeful focus—often referred to as concentration—and the ability to shift attention as required by a stimulus. Being able to ward off distractions is usually seen as part of concentration (28). Vigilance is conceptualized as maintaining attention on an activity for a period of time. There are the needs to respond to more than one aspect of a stimulus or competing stimulus—the capacity to divide attention—alternating with shifts in focus. Lezak and colleagues (21) note that underlying many attention problems is slowed cognitive processing. This can be misinterpreted as a memory disorder (29), as competing stimuli in normal activity interrupt the processing of the immediately preceding stimuli and something is “forgotten,” in common parlance. The discernment of this specific problem is important, as strategies alleviating the effects of slowed processing would be different from those for memory per se. All of these aspects warrant examination, notably in those with a brain disorder, due to the overall effect on functioning and the demand for acquisition of academic and adaptive behaviors throughout childhood. The effects of anxiety about an illness process, its treatment, and demands for coping can all affect attention, and in a competent diagnosis are differentiated from primary brain disruption. Due to the issue of time in competent attention processes, computerized testing has real utility to control for calibration of presentation and response. In the absence of a fully computerized administration, the use of taped auditory stimulus in attention testing allows for standardized presentation increments. Typically, the computerized tasks involve visual stimulus and the taped presentations involve auditory ones. This differentiation between verbal and nonverbal, or auditory versus visual, is necessary to capture these two central aspects of stimulus processing; there may be a distinct difference in one’s ability to maintain visual attention versus auditory attention. This has significant implication with one’s ability to learn and absorb information. The recent development of a battery of attention tasks for children, the Test of Everyday Attention-Children, will be described next. It attempts to cover a number of aspects of attention processes and for the comparison of subtest scores to allow for relative differentiation of components. Inattention, slowness of cognitive processing, and poor concentration have a wide-ranging effect on competent cognitive and adaptive functioning. Other processes may be quite competent, but attention and its aspects can be a primary “rate limiting” factor. These should be addressed in even a screening of functioning, whether at the bedside or in the clinic, both as an overall indicator of current cognitive activity and as a harbinger for developmental problems to come, signaling the need for more stringent monitoring. Commonly used tests are described in Table 3.1. TABLE 3.1 TESTS OF ATTENTION AND SPEED OF PROCESSING INSTRUMENT (REF.) DESCRIPTION COMMENTS Test of Everyday Attention Test of Everyday Attention-Children (TEA-Ch) (30) Batteries of eight or nine tasks for ages 17 and above; TEA-Ch ages 6 to 16 Taps visual/auditory attention including dual tasks; selective, sustained and executive control Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT) Children’s Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (CHIPASAT) (31) Adding pairs of digits presented at four rates of speed, controlled by the audiotape presentations; adult and child forms; ages 8 and above Highly sensitive to deficits in processing speed; sensitive to mild disruption, but can be a stressful test to take, as many items can be missed at normal ranges Continuous Performance Tests (32) Covers a category of tests; visual or auditory stimulus where the individual must respond to a target stimulus in the presence of distractors; various versions for ages 4 and up Many versions exist; sustained, vigilance and inhibition tapped; Connors Continuous Performance Test II and Test of Attention are well known. Symbol Digit Modalities (SDMT) (33) Oral or written; requires visual scanning and tracking to match preset symbol and number pairs Taps information processing; Spanish version with norms; seen as selectively useful. Trail-Making Test (TMT) (34) Subject draws lines to connect consecutively numbered (Part A) and alternating numbers and letters in order (Part B). Ages 9 and up Part of Halstead–Reitan battery; test of speed, visual search, attention, mental flexibility, and fine motor; needs interpretation with other tests; Part B is most sensitive PROBLEM-SOLVING AND EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONING TESTS Executive functioning is a cognitive domain that relates to how other cognitive skills (such as attention, memory, language, and nonverbal reasoning) are executed in different situations. Executive functioning requires self-control over impulses and emotions, the ability to flexibly shift, and skills related to manipulating information in mind, planning, and organization. Deficits in problem solving and executive functioning can have a devastating effect on functioning, just as difficulties with attention. Executive functions have both metacognitive and behavioral components. Cognitive process can be intact, but with executive functioning impairments, the output can be substantially derailed. The basic tasks of life can suffer, along with the ever-present demand in childhood to acquire new skills. These deficits can be more obscured in children than in adults, as there is a natural support of activity by parents or other family members, thus creating a situation where many of these deficits will not be identified until early adulthood. Return to school can be the point at which executive functioning problems can clearly be seen for the first time since an acquired illness or injury. TBI presents a particular vulnerability to deficit in these skills. Executive functions are associated with the frontal and prefrontal areas of the brain, where, due to the mechanisms of closed head injury and the shape of the brain and skull convexities, damage can be focused across the full range of severity. Rehabilitation efforts suffer, both in commitment to the process and in learning strategies to compensate for deficits (23). The competent measurement of executive skills requires a multidimensional approach and can be quite complex (35), given the variety of skills encompassed under the umbrella term of executive function. Testing of these functions imposes a degree of structure required by standardization such that vital elements can be obscured. Attempts at quantification in real-life situations becomes particularly important, as that is where executive skills are often played out. Questionnaires for parents and teachers elicit descriptions of behavior that can be compared to normative expectations. Particularly for parents, this can be useful in understanding the need for treatment. Teachers have a normal sample of age-appropriate peers for comparison in the classroom and can be more aware of such problems. In that circumstance, the questionnaire process can illuminate the component elements to be addressed, as a deficit in classroom performance can be composed of many factors, with differing contributions to the overall presentation. The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), described in the section on “Psychosocial Evaluation,” is an instrument focused on these behaviors. It covers the preschool period through adolescence, as well as a self-report questionnaire for older children, with basic forms for teachers and parents to complete. There are many models, as in attention, as to what comprises these skills and how to measure the components, since it is far from a unitary concept. Again, as in attention, the developmental progress of these skills is a central aspect of the developing child. In the teenage patient, assessment of these skills is vital, as adult-like capabilities for work, driving, and independence can be severely affected and, in the particular case of driving, can have disastrous results. The enactment of graduated driver license requirements for teen driving in some states implies the centrality of these skills and their necessity for that activity. Stepwise exposure and supervision of driving for teens allows for a graduated experience before full driving privileges are granted. Specialized assessment through rehabilitation-based driving evaluations using computer simulation should be considered by a rehabilitation team in any teen with a history of brain disorder. Executive skills include the capacity for planning and flexible use of strategies, and the ability to generate, maintain, and shift cognitive sets; to use organized search strategies; and to use self-monitoring and self-correction, as well as the capacity to utilize working memory. It is distinct from general intelligence, though it does correlate at lower levels of intelligence. Again, as in attention skills, these skills are vulnerable and easily disrupted in many circumstances, as they are largely acquired throughout childhood as an essential central process of competent development. Therefore, deficits acquired can be unknown or hidden until they are called on for future development. The range of tasks is wide, from inhibiting behavior in the absence of visible authority to planning how to accomplish several assignments due at the same time. Though the cognitive aspects are difficult to quantify, the literature on these is substantial. However, the emotional and behavioral aspects of executive skills has not been studied as much (36). Executive skills act to regulate behavior (37,38), inhibit and manage emotions, tolerate frustration, and provide persistence. Notable is the result of limited empathy (ie, taking the position of the other). They are observed collaterally in any sound testing process, but are captured better, to the extent possible, in the “real-world” questionnaire approach discussed previously. The effect of impairment in these skills can be widespread and debilitating, especially as expectations for empathy and self-awareness increase in adolescence. One of the questionnaires does differentiate these two factors. In the BRIEF (131), questions about such skills yield feedback for the behavioral regulation composite, as differentiated from another composite reflecting the cognitive aspect, metacognition composite. A list of tests that cover this wide-reaching domain is listed in Table 3.2. TABLE 3.2 TESTS OF PROBLEM SOLVING AND EXECUTIVE FUNCTION INSTRUMENT (REF.) DESCRIPTION COMMENTS Halstead Category (HCT) (39) Versions exist for ages 5–9 and 9–14, as well as through adulthood; part of Halstead-Reitan battery Machine and booklet forms; measures conceptualization and abstraction abilities Wisconsin Sorting Test (WCST) (40) Revised manual offers norms for ages 6.5 and above. Computerized and standard administration Requires inference of correct sorting strategies and flexible use Tower of Hanoi (TOH) (41) Computer and standard administration; ages 4 and up Taps working memory, planning, rule use, and behavioral inhibition Tower of London—Drexel, 2nd Edition (TOLDX) (42) Arrange balls on pegs to match picture; norms for 7 and up Taps inhibition, working memory, anticipatory planning Stroop Color-Word Test (43) Well-known test, quick administration in paper form; several versions Test of inhibition, selective attention, and switching sets Matching Familiar Figures (MFFT) (44) Must find identical match for stimulus picture; ages 6 and up Measures impulsivity Fluency Tasks Verbal and Design Speeded tasks of response generation to verbal and nonverbal stimuli Taps self-monitoring, initiating, and shifting; included in many batteries Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D–KEFS) (45) Battery of six subtests; ages 8 and above Battery aids comparison of subtest scores

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

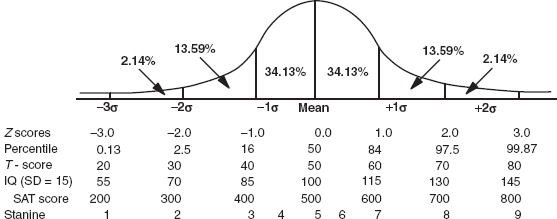

Full access? Get Clinical Tree