Psychological and Behavioural Considerations in ROM Rehabilitation

A dancer presented in my clinic complaining of severe shoulder range of movement (ROM) limitation and pain. He was previously diagnosed as having “joint damage”. He consequently became fearful of re-injury and withdrew from activities which challenged the full shoulder ranges. However, on examination it emerged that his condition was likely to be the stiff phase of frozen shoulder. It was explained to him that frozen shoulder, although a painful condition, is not associated with damage; the joint and its tissues are fully intact, shortened/thickened and sensitive. In the following session, a week later, the patient demonstrated a dramatic increase in shoulder ROM. He explained that once he realized that movement would not damage the joint he could tolerate the discomfort and used the arm in full range during the daily activities.

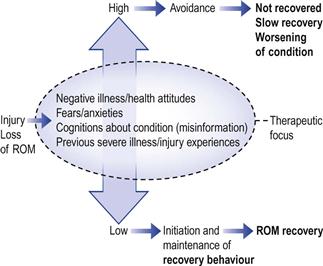

This example serves to highlight that movement limitations can be self-imposed by beliefs and anxieties associated with injury and pain. These psychological and cognitive factors can be as ROM limiting as physical or neurological impediments (Fig. 11.1). Sometimes treatments that successfully restore the physical limitations of ROM may fail to improve functional activities unless these anxieties are addressed.

This chapter will explore the following topics:

Can ROM limitations have psychological–behavioural origins?

Can ROM limitations have psychological–behavioural origins?

Could psychological factors influence ROM recovery?

Could psychological factors influence ROM recovery?

How can we reassure the patient that end-range movement is OK?

How can we reassure the patient that end-range movement is OK?

Activity Avoidance as ROM Limitation

The patient described above is probably no different from other individuals who have been injured or are in pain. There is a natural fear that movement may cause re-damage or increase the pain intensity.1 As a consequence, individuals may avoid certain ranges of movement and withdraw from activities which they believe will be painful or harmful.2–10 Such self-imposed limitations can be seen in spinal conditions as reduced trunk ROM, restricted overhead use of the arm in shoulder conditions and reduced stride length in lower limb conditions. This behaviour would have a negative impact on ROM recovery. It would sustain the dysfunctional motor and tissue adaptation associated with the ROM loss (Ch. 4).11–14 In contrast, behaviour that frequently challenges movement to the full is essential for recovery. Habitual use of the body drives the positive adaptive processes that underlie ROM normalization (Ch. 4).

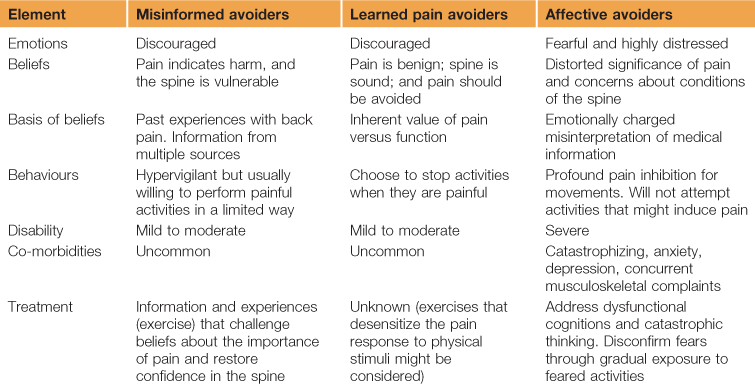

Activity avoidance can arise from several factors (Table 11.1):15 negative beliefs about the condition resulting from inaccurate, misleading or conflicting information from individuals with similar conditions, various health-care practitioners and the media. Activity avoidance can also come about through the experience of pain during specific activities, forming a learned association between pain and movement.15 This association may be transferred to movement ranges or tasks which are neither harmful nor painful.7 For example, patients who recover from back pain tend to maintain a restricted movement strategy even when they are pain-free.7

Table 11.1

Characteristics of subclassification of patients with problematic fear-avoidance beliefs

Modified and reprinted from: Rainville J, Smeets RJ, Bendix T, et al. Fear-avoidance beliefs and pain avoidance in low back pain: translating research into clinical practice. Spine J 2011;11(9):895–903, with permission from Elsevier.

Psychological factors that predate the patient’s condition could also contribute to avoidance behaviour. Individuals who are naturally anxious may transfer their fears and avoidance behaviour to their current condition.15 This phenomenon was demonstrated in a large population study on whiplash injury.16,17 Individuals who exhibit more fear avoidance, who were anxious and depressed and those who had negative illness behaviour pre-injury tended to increase their reporting of a whiplash injury, experience more pain and were more likely to receive disability support.16–18 Similarly, the development of serious back pain disability can be predicted more accurately from the psychosocial history of the individual than from structural/degenerative changes in the spine.19

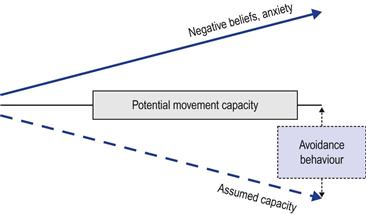

The cognitions and anxieties about movement may feed a widening gap between an assumed incapacity and the current “potential” physical capacity (Fig. 11.2). For example, in patients with acute low back pain, pain-related fears and catastrophizing can be more indicative of their physical ability to lift than pain intensity itself.20 This gap tends to widen with conditions of longer duration or greater intensity.12,13,21,22 Hence, an important component of ROM management is to narrow this gap by redefining and exploring with the patient what degree of loss is assumed and what is real; and this can sometimes be difficult to establish.

Reassurance

It was demonstrated in patients with chronic back conditions that pain and functionality can improve as much with cognitive–behavioural approaches as with physical exercise.23,24 It seems that both treatment modalities share a similar underlying process for improvement. They both convey a message to the patient that movement is OK, alleviating the anxiety/fear/catastrophizing associated with the condition.23,25,26 Reassurance can have a profound influence on recovery. Cognitive, psychological and behavioural transformations can help to reduce pain, improve movement capacity, facilitate a return to more normal occupational and recreational activities and reduce health-seeking behaviour.23,27–33

Reassurance can be provided in different forms depending on the factors that underlie the avoidance behaviour. Cognition-related avoidance can be managed by providing the patient with information about the condition.15 Experience-related avoidance can be alleviated by a gradual reintroduction of tasks and movement ranges from which the patient withdrew (graded exposure), as well as cognitive reassurance.15,34 Patients who exhibit affective, anxiety-related avoidance may partly respond to behavioural forms of reassurance but may not respond well to reasoning or cognitive reassurance. These patients may benefit from psychological counselling as part of their overall management.15

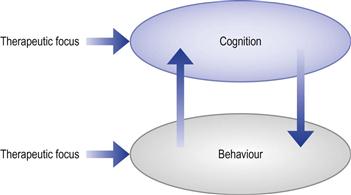

Cognition and behaviour are inseparable – a change in cognitions about the condition will influence the person’s recovery behaviour. Equally, challenging behaviour by introducing non-aggravating movement experiences can influence how a person perceives their condition and embolden them to experiment with movement which they fear (Fig. 11.3).35 Hence, reassurance can be provided cognitively or behaviourally, but usually it is a mixture of both.

Cognitive reassurance

When an individual experiences pain or movement limitation they create a personal story about their condition. This internal narrative is derived from numerous sources and previous experiences. It often contains negative messages that are mixed with anxiety and catastrophic thoughts (“shoulder is damaged, seen torn capsules on the internet, a friend had surgery and was unable to play tennis again, will I ever be able to return to playing tennis?”…). An important part of management is to help the patient turn negative narratives into positive ones.

There are several ways in which patients can be helped to transform their cognitions/narratives. Providing patients with relevant information about their condition is an important part of this process;36–38 in particular, information which they can do something about.39 Individuals who have a better understanding of their condition are more likely to take up activities that challenge their losses. For example, the patient with the frozen shoulder was given information that emphasized the positive aspect of the condition – that it was self-limiting and unlikely to result in any disability. There was an emphasis on describing the mechanism associated with tissue adaptation and how this process could be facilitated by their behaviour and daily activities. There was also a detailed explanation of the difference between the pain of injury and the pain of sensitization – thereby, dissociating pain from damage. Using the same approach, patients who have tissue damage underlying their ROM losses can be informed about tissue repair processes and the importance of movement in supporting these processes, rather than focusing on the extent of tissue damage.

Generally, there is little therapeutic value – and potentially even a negative effect – in using anatomical and biomechanical models for pain or diagnosis that do not support return to function.40 Patients’ fears and anxieties may be increased by a detailed description of underlying damage, and use of terms such as “deterioration” or “degeneration”. This may be partly due to the disempowering nature of this form of information which focuses on factors that are outside the patient’s control.

Focusing on the “abled self” rather than the “disabled self” can also be part of reassurance – pointing out to patients what they can do, rather than what they cannot do. For example, patients with chronic back pain can be virtually symptom-free during demanding physical activities such as gardening, playing football or even windsurfing. This would be pointed out during the session, focusing on these “abled” activities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree