Chapter 11 Prognosis of Whiplash-Associated Disorders

There is little doubt that soft tissue injuries of the cervical spine can leave persisting symptoms.1 Jackson2 discussed posttraumatic chronic cases in patients whose symptoms persisted well beyond the anticipated time. She noted that because of the tendency to dismiss these patients with a psychological diagnosis that they will “be relieved of worry and anxiety knowing that they have explainable reasons for their symptoms.” Hohl,3 in 1974, reported that lasting symptoms are intermittent neck ache, stiffness, and headaches often with interscapular and upper extremity pain and numbness. These findings are consistent with a more recent study by Squires, Gargan, and Banister.1 They noted that in the patients that they studied, symptoms did not improve after settlement of litigation. This too, is consistent with the published literature of Balla and Moraitis in 19704 and Mendelson in 1982.5 Parmar and Raymakers6 found that whereas most patients reach their final state after 2 years, a small percentage improves with time.

Holm8 stated that in the early management of persons with whiplash-associated disorders, it is important to consider psychological status, expectations for recovery, and social circumstances in addition to the biomedical components of the injury. These factors must all be considered in the prognosis of patients with whiplash trauma. The natural course of recovery and the prognosis for whiplash-associated disorders are controversial. Some claim that such injury and its prognosis are solely determined by the physical injury.9–11 Others are critical of this point of view, stating that psychosocial factors are relevant.1,8 Some factors are known to contribute to a poor prognosis.

Prognostic Factors

Despite observations of bias with regard to the prognosis of whiplash victims in the literature,8,12 there is reasonable agreement on several factors affecting prognosis.8 These factors include severity of the injury,3,13 position of the head at the time of impact,8,13,17 gender,8,14–16 and age.1,13–15 Holm8 also includes psychosocial factors that contribute to poor prognosis, such as lower education, passive coping strategies, poor mental health, and low pain tolerance. Despite various possible explanations for the differences in the course of recovery after whiplash injury, the magnitude of the importance of a patient’s prognosis is individual, and management must be patient centered to achieve optimal results.

Severity of Injury

Severity of injury can produce an unfavorable prognosis if extensive soft tissue damage occurs. The presence of fracture or dislocation need not be present for the patient to experience ongoing pathology or dysfunction. In a study of patients with complaints of headache, 27% were symptomatic 6 months post-accident, and another study found that 42% of their cohort were symptomatic an average of 2 years post-accident. Squires et al1 found that 70% of the patients in a 15-year follow-up study continued to complain of symptoms referable to the accident 15 years later. These ranged from mild to severe. This is much higher than the 27% that remained symptomatic in a 2-year post-injury study that reported the prognostic significance of the initial severity of injury.13

Instability must be ruled out in late whiplash symptoms. Instability cannot be diagnosed by static tests.18 A boggy sensation with no abrupt end feel on palpation is suggestive of instability, and dynamic imaging (see Chapter 5) is required for confirmation. In a case series, reported that when these patients were investigated with functional magnetic imaging (see Chapter 5), dramatic findings were obtained.18 Imaging showed capsule tears and instability of the lateral atlantoaxial joint, and scar tissue around the odontoid process with cord impingement upon rotation of the head. This pathology was consistent with the patient’s complaints and the abnormalities confirmed at surgery. The patients’ symptoms were previously dismissed as psychogenic, and the possibility of pathology was ignored. Bogduk notes that the psychogenic model of whiplash-associated disorders, although attractive and convenient, is neither reliable nor valid.18

Position of Head at Time of Impact

Sideways position of the head at the time of impact tends to produce more severe injury and a poorer prognosis.8,13,17 If the head is turned sideways at the time of impact, as when looking in the rearview mirror, the force of the impact must be resisted by the unilateral anterior strap muscles on the side facing forward. Damage to these muscles not only produces neck pain but also headache (see Chapters 5, 6, and 7) and upper extremity symptoms on the same side (see Chapter 6). Persistent neck and upper extremity pain can significantly produce a poorer prognosis. Pain maps in a 1996 follow-up study1 reinforce the view of Hohl3 that radiating pain is associated with more severe disability. Unilateral involvement of facet joints should also be considered in these cases. (See Chapter 8.) Bogduk and Marsland19 noted the distribution of pain conforms more closely to radiation from the facet joints rather than dermatomes.

Gender

A number of authors have found that pain and disability did not vary with gender.17,21,22 A poorer prognosis for whiplash-associated disorders in females has been explained in terms of both biological and social factors.8,20 Krafft et al16 indicate that women run a higher risk of sustaining a whiplash injury when involved in a car crash. This may be due to their lighter frames, less-protective musculature, and their tendency to drive smaller vehicles compared with males. Croft23 notes that although females may be more at risk of acute injury, they are roughly equal with males for the likelihood of developing late whiplash. Squires et al1 reported that women and older patients had a worse outcome after 15 years.

Age

There appears to be more agreement that age is a prognostic factor for a worse outcome than gender.1,17,20,24–25 Elderly patients in the long term tend to have more symptoms (pain, among others) compared with younger patients.17,25 Age has been found to significantly predict the outcome of disability, with high age corresponding to high ratings of disability.24

Psychological and Psychosocial Factors That Delay Recovery

Holm8 states that when reviewing the literature on prognosis after whiplash injury, it becomes evident that biomedical, psychological, and social factors play a role and also interact. Bogduk26 notes that review of the literature reveals a considerable amount of biomechanical and experimental data that substantiates a diverse organic basis for patient’s symptoms and that the symptoms of whiplash injury are poorly understood or misrepresented as due to neurosis. Too often, patients’ complaints have been dismissed as psychogenic and unrelated to the trauma of whiplash injury.2,18 In the current multidimensional model of musculoskeletal pain and patient-centered care, psychological and psychosocial factors must be considered as having a role in the perpetuation of symptoms from whiplash trauma. However, the relationship between pain and disability, physical impairment, and psychosocial variables is complex and not fully understood.27 Clinicians should maintain an open mind with respect to potential interrelationships between these variables.28 There has been a paucity of investigations of pain and disability related to the cervical spine compared to that of low back pain.28 Extrapolation from findings of studies of low back pain may not be valid. Recent evidence demonstrates that the development and perpetuation of neck pain probably involves psychological factors unique to this condition.29–31 In an earlier study, evidence of psychological disturbance was found in approximately half of the patients in the 15-year follow-up study by Squires et al.1 In a 1992 study, Gargan, Bannister, and Main7 found that patients who were psychologically normal at the time of injury developed abnormal psychological profiles if symptoms persisted for 3 months. Wallis, Lord, and Bogduk32 demonstrated that psychological distress resolved following pain relief using zygapophyseal joint blocks in patients with chronic whiplash-associated disorders. This suggests that ongoing psychological distress may be dependent upon symptom persistence.

Posttraumatic stress symptoms, when misdiagnosed or inappropriately treated, can significantly delay recovery from whiplash injury.31,33 Symptoms may include intrusive thoughts and/or images of the crash, avoidance behavior such as avoiding driving or avoidance through substance abuse, and hyperarousal such as panic attacks, hypervigilance, and sleep disturbance.28 The presence of posttraumatic stress symptoms is associated with greater levels of pain and disability, more severe whiplash complaints, and poor functional recovery from the injury.17,33 Whiplash injury differs from other causes of neck injury in that it is precipitated by the trauma of a vehicle crash. Post-accident, those with a whiplash diagnosis such as neck pain are likely to have a posttraumatic stress disorder at 12 months compared to those who did not report neck pain.34 A diagnosis of moderate posttraumatic stress disorder in patients suffering from whiplash-associated disorder has been found to be a strong predictor of poor outcome.35,36

Educational background has been found to be a factor in the prognosis of whiplash injuries.8 Those with a low educational level appear to be more vulnerable to daily hassles and stress following whiplash injury.37 Chronic patients with whiplash-associated disorders appear to be more vulnerable and react with more distress than healthy people to all kinds of stressors. Stress responses probably play an important role in the maintenance or deterioration of whiplash-associated complaints. In the early management of patients with whiplash-associated disorders, it is important to consider psychological status, expectations for recovery, and social circumstances, in addition to the biomedical components of the injury.

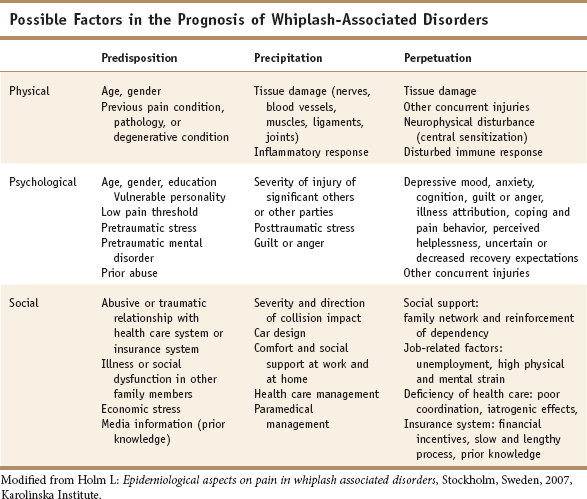

Since Engel38 proposed the biopsychosocial model in 1977, an alternative to the biomedical model of illness or disease has been studied. As opposed to the biomedical model, the biopsychosocial model emphasizes interactions among the various aspects of pathology, psychology, and behavioral adaptations in clinicians’ attitudes, in patients, and in the society. A biopsychosocial model, coupled with a patient-centered paradigm,39 appears to be the most appropriate concept for understanding the clinical course of whiplash-associated disorders. Holm,8 building on and modifying Gallagher’s diagnostic matrix, adapted this matrix to whiplash-associated disorders (Table 11-1). This biopsychosocial net presents factors that should be considered in the prognosis of patients suffering from whiplash-associated disorders. The biopsychosocial model that considers an effect of cultural expectation, cultural factors that generate symptom amplification and attribution, as well as the possibility that physical and psychological causes coexist, seems more helpful.40

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree