Chapter 4 Principles of Adjustive Technique

Chiropractors must maintain the necessary diagnostic skills to support their roles as primary contact providers. There is, however, a wide range of choice in the chiropractor’s scope of practice. Therapeutic alternatives range from manual therapy and spinal adjustments to physiologic therapeutics and exercise, nutritional and dietary counseling.1,2

Although there is great variation in scope of practice from state to state, nearly all chiropractors use a variety of manual therapies with an emphasis on specific adjustive techniques. 1,3 4 5 6 7 8 The preceding chapters focused on the knowledge, principles, examination procedures, and clinical indications for applying adjustive therapy. This chapter focuses on the knowledge, mechanical principles, and psychomotor skills necessary to effectively apply adjustive treatments.

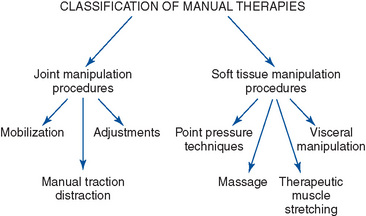

Classification and definition of manual therapies

Manual therapy includes all procedures that use the hands to mobilize, adjust, manipulate, create traction, or massage the somatic or visceral structures of the body.9 They may be broadly classified as those procedures directed primarily at the body’s joint structures or soft tissue components (Figure 4-1).

Joint manipulative procedures

Joint manipulative therapies are manual therapies, the primary effect of which is on joint soft tissue structures (Box 4-1). They are physical maneuvers designed to induce joint motion through either nonthrust techniques (mobilization) or thrust techniques (adjustment or thrust manipulation). They are intended to treat disorders of the neuromusculoskeletal (NMS) system by decreasing pain and improving joint range and quality of motion. This leads to their common application in the treatment of NMS disorders that are associated with joint pain or joint hypomobility (subluxation/dysfunction).

BOX 4-1 Manual Therapy Terminology

Manual therapy

Procedures by which the hands directly contact the body to treat the articulations or soft tissues.16

Joint manipulation

(1) Joint manipulative therapy broadly defined includes all procedures in which the hands are used to mobilize, adjust, manipulate, apply traction, stimulate, or otherwise influence the joints of the body with the aim of influencing the patient’s health; (2) a manual procedure that involves a directed thrust to move a joint past the physiologic ROM without exceeding the anatomic limit;16 (3) skillful or dexterous treatment by the hand. In physical therapy, the forceful passive movement of a joint beyond its active limit of motion.

Adjustment

(1) A specific form of joint manipulation using either long- or short-leverage techniques with specific anatomic contacts. It is characterized by a low-amplitude dynamic thrust of controlled velocity, amplitude, and direction. Adjustments are commonly associated with an audible articular crack (cavitation). (2) any chiropractic therapeutic procedure that uses controlled force, leverage, direction, amplitude, and velocity, which is directed at specific joints or anatomic regions. Chiropractors commonly use such procedures to influence joint and neurophysiologic function.16

Joint mobilization

(1) Form of nonthrust joint manipulation typically applied within the physiologic range of joint motion. Mobilizations are passive rhythmic graded movements of controlled depth and rate. They may be applied with fast or slow repetitions and various depth. Although joint mobilization is not commonly associated with joint cavitation, deep mobilization (grade 5) may induce cavitation; (2) movement applied singularly or repetitively within or at the physiologic range of joint motion, without imparting a thrust or impulse, with the goal of restoring joint mobility;16 (3) manual traction-distraction: a form of mobilization producing a tractional or separating force. It may be accomplished manually or with mechanical assistance and can be sustained or intermittent.

When joint dysfunction/subluxation syndrome (hypomobility or malposition) is treated, the adjustive thrust or mobilization is typically delivered in the direction of reduced joint motion to restore normal motion and alignment. For example, if the lumbar spine has a restriction in right rotation, the doctor thrusts to induce more right rotation in the affected region. In some instances, the therapeutic force may be delivered in the relatively nonrestricted and pain-relieving direction. This is most common when acute joint pain and locking limit movement in one direction, but still allow distraction of the joint capsule in another direction.10 11 12 Under these circumstances, therapy is most commonly directed at inducing separation of joint surfaces. The goal is to inhibit pain and muscle guarding and to promote flexible healing.

Adjustment

Adjustments are the most commonly applied chiropractic therapy.3 4 5 They are perceived as central to the practice of chiropractic and the most specialized and distinct therapy used by chiropractors. 3,4,13 Specific reference to adjustive therapy is incorporated in the majority of state practice acts, and it is commonly cited as a key distinguishing feature of chiropractic practice.14 Although adjustive therapy is central to most chiropractic practices, the authors do not want to impart the impression that chiropractors should limit their clinical care to adjustive treatments. Patient management and treatment plans should be based on the best available evidence, clinical judgment, and patient preferences. There are circumstances in which the best standard of care for a given NMS disorder involves the application of nonadjustive treatments singularly or in combination with adjustive therapy. Other therapies commonly applied by chiropractors include joint mobilization and light-thrust techniques; soft tissue massage and manipulation; physical therapy modalities; and instruction on exercise, ergonomics, lifestyle, and nutrition.

Unfortunately, the common use of adjustments by chiropractors has not led to a clear and common understanding of the defining characteristics of an adjustment.14,15 A mid-1990s consensus process made major strides in reaching consensus on many of the chiropractic profession’s unique terms.19 However, several key terms within this document lack clarity. At issue is whether the definitions presented for adjustment and manipulation are clear and distinct or so broad that they have limited descriptive value.

Historically, adjustive therapy was defined primarily in the context of the doctor’s therapeutic intentions. If the doctor applied a treatment procedure with the intention of reducing a joint subluxation, it was considered an adjustment.17,18 Based on this premise, any procedure delivered by a chiropractor and directed at reducing joint subluxation could be considered an adjustment. This approach results in a wide variety of significantly different physical procedures all being classified as adjustments.

The 1990s consensus process appropriately moved the focus away from defining adjustments based on therapeutic intention and toward defining an adjustment based on its physical characteristics. However, the definition maintained a very broad and inclusive approach. Adjustments were defined “as any chiropractic therapeutic procedure that utilizes controlled force, leverage, direction, amplitude and velocity.”19 The definition did not limit the application of adjustments to the joints of the body, but specified that adjustments could be delivered to any anatomic region (see Box 4-1, Adjustment 2). In this context, it is difficult to perceive a chiropractically applied procedure that would not be classifiable as an adjustment. A wide variety of diverse procedures (thrust and nonthrust joint manipulation, adjustment, massage, manual or motorized traction, etc.) all involve force, leverage, direction, amplitude, and velocity. More than 100 different named technique systems have been identified within the chiropractic profession, and most of them call their treatment procedure an adjustment (see Appendix 1).20 A number of these procedures do not share discrete physical attributes and may not be equivalent in their physical effects and outcomes. The profession needs to objectively evaluate and compare the effectiveness of chiropractic therapeutic procedures. This cannot be accomplished without physically distinct classifications of commonly employed manual therapies. Until this issue is addressed, it will be difficult for the profession to determine which therapies are most effective and in what clinical conditions.

The basis for distinguishing and classifying adjustive procedures should incorporate their measurable characteristics and should not be based solely on therapeutic intention. Separating the physical components of an adjustment from the rationale for its application does not diminish it significance. As stated by Levine, “It is the reason why techniques are applied and why they are applied in a certain manner that distinguishes chiropractic from other healing disciplines.”21

The historically broad perspective on and definitions of what constitutes an adjustment have led to a wide variety of procedures being classified as adjustive methods. The assumption that all forms of adjustment, as presently defined, are equivalent must be avoided.22 As discussed previously, many in the profession do not equate an adjustment with a thrust, and a number of chiropractic technique systems do not incorporate thrust procedures.19 In addition to differences that may exist in the form of applied treatment, many technique systems attempt to distinguish themselves not by the attributes of the adjustment they perform, but rather by what they claim to be their unique underlying biomechanical and physiologic principles and rationale.

Despite the variety of procedures that have been labeled as adjustments, most share the common characteristic of applying a thrust. It is this attribute that we propose as the central defining and distinguishing physical feature of the chiropractic adjustment. 9,23,24 Although amplitude and velocity of the adjustive thrust may vary, it is a high velocity–low amplitude (HVLA) ballistic force of controlled velocity, depth, and direction. With this in mind, we suggest the following definition: The adjustment is a specific form of direct articular manipulation, using either long- or short-leverage techniques with specific contacts characterized by a dynamic thrust of controlled velocity, amplitude, and direction (see Box 4-1, adjustment 1). Adjustive contacts are usually established close to the joint being treated, and the thrust is delivered within the limits of anatomic joint integrity. Adjustive therapy is commonly associated with an audible articular “crack,” but the presence or absence of joint cracking should not be the test for determining whether or not an adjustment has been performed.

Properly applied adjustments are commonly painless, although the patient may experience some momentary, minimal discomfort. A short-duration mild increase in local soreness after manipulation has been reported in up to 50% of patients treated with manipulation and should not be considered an inappropriate response.25 Adjustments should not be forced when preloading a joint in the direction of intended manipulation induces pain or protective patient guarding and resistance. Adjustive procedures that induce discomfort during application should be considered only if they are directed at increasing joint mobility.

Categorization of Adjustive Procedures

Various proposals have been made to further subclassify adjustive thrust procedures. However, most classification schemes suffer from the central problem of beginning with an unworkably broad definition of adjustment. This creates an unnecessary burden on authors who then try to subclassify adjustments by the very attributes that are commonly used to distinguish adjustments from other forms of manual treatment. One common approach is to distinguish adjustments by the degree of applied velocity. It is not uncommon to see references in the chiropractic literature and trade magazines in which different methods are presented and promoted as low-force or nonforce methods. This carries an inference that these procedures are different from other adjustive techniques and are associated with less peak force. These descriptions commonly do not explain if the procedures are applied with a thrust, nor do they explain how much actual force is involved or how they truly compare with other adjustive procedures. Furthermore, measurements of adjustive preload, peak force, and amplitude appear to vary within the same adjustive methods. When the same adjustive methods are applied at different anatomic regions or on different patients, the preload, rate of velocity, and peak velocity change significantly.26 These noted differences are no doubt the product of each doctor’s trained ability to note and modify his or her adjustive procedures relative to the encountered joint resistance of each spinal region and patient, rather than a conscious effort to use a different adjustive procedure. It is doubtful that any meaningful distinction can be achieved by trying to subclassify adjustments by moderate differences in applied velocity. How would the velocity be measured in day-to-day practice, and how much of a change would be necessary to distinguish one method from the other? Nothing is gained by redefining a joint mobilization as a low-velocity, moderate-amplitude adjustment simply because it is performed by a chiropractor.

In an attempt to be more precise in the distinction, classification, and validation of chiropractic procedures, Bartol15,27 and the Panel of Advisors to the American Chiropractic Association Technique Council proposed an algorithm for the categorization of chiropractic treatment procedures. This scheme includes criteria for velocity, amplitude, and the use of manual or mechanical devices to deliver the adjustment. These models were presented at the Sixth Annual Conference on Research and Education and are commendable attempts to further distinguish adjustive methods.28 However, they too lack any clear criteria for distinguishing various levels of high- and low-velocity or high- and low-amplitude adjustments. The criteria for distinguishing manual from mechanical methods are valuable and easily discernible, but they leave a number of other important qualities and potential distinguishing features unaddressed. The criteria include patient positioning (PP), contact points (CPs), leverage, and type of thrust.

To distinguish one adjustive procedure from the other, we suggest a system that begins with the assumption that adjustments are HVLA thrust procedures, which can be further differentiated and subcategorized by the components listed in Box 4-2. The suggested method incorporates elements used by the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners on Part IV of the Practical Adjustive Examination and avoids the dilemma and technological difficulties encountered in trying to differentiate adjustments by minor changes in velocity and depth of thrust.

Specific versus general spinal adjustments

Specific adjustments involve procedures used to focus the adjustive force as much as possible to one articulation or joint complex. Specific adjustments typically involve the application of short-lever contacts (Figure 4-2). Specificity is assumed to result from establishing adjustive contacts over or near the targeted joint with precise attention given to adjustive vectors. General adjustments involve procedures that are assumed to have broader sectional contacts and effects, mobilizing more than one joint at a time. They are applied when a regional distraction of a group of articulations is desired and commonly involve longer levers and multiple contact sites (see Figure 4-2). Nwuga29 used the term nonspecific in this manner and stated that most of the techniques described by Cyriax30 would fall into this category. Grieve31 uses the terms localized and regional to distinguish between procedures that affect a single joint or a sectional area. Also, the term general has been used to denote the nonspecific, regional, or sectional forms of manipulation.32 Therefore techniques considered to be nonspecific use broad and long-lever contacts taken over multiple sites with the purpose of improving motion or alignment in an area that is generally stiff or distorted. Grice and Vernon33 suggest that this type of procedure is indicated to free general fixations or reduce general muscle spasms, such as those seen in spinal curvatures.

The chiropractic profession has emphasized short-lever procedures, theorizing that these are more precise in correcting local subluxation/dysfunction without inducing stress or possible injury to adjacent articulations. This may be especially pertinent in circumstances with adjacent joint instability. Recent research investigating some of the biomechanical assumptions of the specificity paradigm has raised some significant challenges to this model.34,35 This research does not diminish the demonstrated clinical effectiveness of adjustive therapy,36 37 38 but it does bring into question whether precise joint specificity is achievable or essential for adjustive therapy to be clinically effective.34 Further discussion of this topic is presented later in this chapter under the application of adjustive therapy section.

Chiropractic technique

Many chiropractic diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (techniques) have been developed empirically in the profession by an individual or association of individuals. These techniques are commonly then assembled as a system, incorporating theoretic models of joint dysfunction with procedures of assessment and treatment. Appendix 1 is a list of system techniques.

Manipulation

In contrast to the broad definition of adjustment, the 1990s consensus project defined joint manipulation in more narrow terms and limited its application to joint-thrust procedures (see Box 4-1, joint manipulation 2).16 This is not uncommon, and it is becoming the norm. However, joint manipulation is also commonly used in a broader context (see Figure 4-1 and Box 4-1, adjustment 1). In this context, manipulate means to skillfully use the hands to move, rearrange, and alter objects. When applied to manual therapy and biologic tissue, it has not historically been limited to high-velocity thrust procedures. It frequently had a broader application, which encompassed a number of more specific procedures applied to soft tissues and joints, such as soft tissue manipulation, massage, and joint mobilization (see Box 4-1).

Joint mobilization

Joint mobilization in contrast to adjustive therapy does not use a thrust.9,39 Joint mobilization is applied to induce movement through a series of graded movements of controlled depth and rate without a sudden increase in velocity. It is a common mistake to consider mobilization as a procedure that cannot induce movement into the end range of the elastic zone (paraphysiologic space). Deep joint mobilization may be associated with an audible crack (cavitation). Joint cavitations do not occur as frequently with mobilization as they do with thrust procedures, but the presence or absence of joint cavitation during the procedure does not distinguish a mobilization from an adjustment or thrust manipulation. Joint mobilization procedures are detailed in Chapter 7.

Manual traction-distraction

Manual traction-distraction is another form of manual therapy used to mobilize articular tissues. Traction is not a unique and separate form of treatment, but is simply one form of passive mobilization.40 Therefore, the distinction between joint mobilization and manual traction-distraction is not clear, and the separation may be arbitrary. When the technique is applied to articular tissues, the goal is to develop sustained or intermittent separation of joint surfaces. In the field of manual therapy, traction-distraction is performed through contacts developed by the clinician and is often aided by mechanized devices or tables.

Traction techniques are thought to aid in the application of an adjustment by first allowing physiologic rest to the area, relieving compression that results from weight bearing (axial loading), applying an imbibing action to the synovial joints and discs, and opening the intervertebral foramina. Many of these procedures are also quite useful for elderly patients when an HVLA thrust may be contraindicated. Moreover, traction maneuvers produce long-axis distraction in the joint to which they are applied. There is a long-axis distraction movement of joint play (JP) at every synovial joint in the body.41 Yet in the spine, the fact that this important joint movement is necessary for normal function of the joint is mostly ignored or forgotten. Perhaps this is because testing for long-axis distraction of the spinal joints can be difficult to elicit manually.

The term traction refers to the process of pulling one body in relationship to another, which results in separation of the two bodies.42 Traction is a passive translational movement of a joint that occurs at right angles to the plane of the joint, resulting in separation of the joint surfaces. Kaltenborn42 divides manual traction into three grades of movement. In the first, there is no appreciable joint separation, because only enough traction force is applied to nullify the compressive forces acting on the joint. The compressive forces are a result of muscle tension, cohesive forces between articular surfaces, and atmospheric pressure. The second effect produces a tightening in the tissue surrounding the joint that is described as “taking up the slack.” The third grade of traction requires more tractive force that produces a stretching effect into the tissues crossing the joint. The principal aim of treatment is restoration of normal, painless range of motion (ROM).

Traction can be applied manually or mechanically, statically or rhythmically, with a fast or slow rate of application. The force applied may be strong or gentle and applied symmetrically or asymmetrically. The effects of traction are not necessarily localized, but may be made more specific by careful positioning. Although traction has focused mostly on the lumbar and cervical spine regions, there are descriptions for the application of rhythmic traction to all regions of the spine and extremities. Furthermore, the indications for traction include changes that are common to most synovial joints in the body. Chapter 7 provides detailed descriptions of traction techniques.

Soft tissue manipulative procedures

Soft tissue manipulative procedures (Box 4-3) are physical procedures using the application of force to improve health. This category includes techniques designed to manipulate, massage, or stimulate the soft tissues of the body.9 “It usually involves lateral stretching, linear stretching, deep pressure, traction and/or separation”39 of connective tissue. They may be applied to either articular or nonarticular soft tissues.

BOX 4-3 Soft Tissue Manipulative Procedures

Modified from Barral JP, Mercier P: Visceral manipulation, Seattle, 1988, Eastland Press.

Soft tissue manipulative procedures are used to alleviate pain; to reduce inflammation, congestion, and muscle spasm; and to improve circulation and soft tissue extensibility.31 In addition to their use as primary therapies, they are frequently used as preparatory procedures for chiropractic adjustments. Soft tissue manipulation tends to relax hypertonic muscles so that when other forms of manual therapy are applied, equal tensions are exerted across the joint.

There are numerous named soft tissue manipulative procedures; Box 4-3 provides a list of some of the common methods that are used in manual therapy. Chapter 7 provides detailed descriptions of nonthrust joint mobilization and soft tissue manipulative procedures.

Mechanical spine pain

Conditions inducing pain and altered structure or function in the somatic structures of the body are the disorders most frequently associated with the application of manual therapy. The causes and pathophysiologic changes that induce these alterations are likely varied, but are commonly thought to result from nonserious pathologic change commonly lumped under the category of nonspecific spine pain. In the low back, 85% to 90% of complaints are estimated to fall within this category.43,44 Specific pathologic conditions, such as infection, inflammatory rheumatic disease, or cancer, are estimated to account for approximately 1% of presenting low back pain (LBP) complaints.45 Nerve root (NR) pain caused by herniated disc or spinal stenosis is estimated to account for 5% to 7% and referred LBP resulting from visceral pathologic conditions accounts for approximately 2%.45

The differentiation of mechanical from nonmechanical spine pain should begin with an evidence-based clinical examination. A “diagnostic triage” process based on a thorough history and brief clinical examination is recommended by numerous national and international guidelines as an efficient first step.46 47 48 This process is most commonly referenced relative to LBP, but is applicable to any axial spine pain complaint. The triage process is structured to identify any red flags, ensure the problem is of musculoskeletal origin, and classify suspected musculoskeletal problems into three broad categories before beginning treatment. The three major categories are back pain caused by a serious spinal pathologic condition, back pain caused by NR pain or spinal stenosis, or nonspecific (mechanical) LBP. If the history indicates the possibility of a serious spinal pathologic condition or NR syndrome, further physical examination and indicated testing should be conducted before considering treatment.

The chiropractic profession postulates that nonspecific back pain is not homogeneous and a significant percentage of mechanical spine pain results from altered function of spinal motion segments. Recent efforts have been directed toward investigating models of differentiating nonspecific spine pain patients into specific subcategories.49,50 Evidence is emerging that categorization and “subgrouping” of nonspecific (mechanical) spine pain patients can lead to improved patient outcomes.51,52 Although models for subgrouping nonspecific spine pain patients have been based on both diagnostic and treatment categories, 50,53 both share the premise that grouping patients by shared collections of signs and symptoms will lead to category-specific treatment and more effective outcomes.

Joint subluxation/dysfunction syndromes

Although the evaluation of joint function is a critical step in the process of determining whether and how to apply adjustive therapy, the identification of subluxation/dysfunction does not conclude the doctor’s diagnostic responsibility. The doctor must also determine if the dysfunction exists as an independent entity or as a product of other somatic or visceral disease. Joint subluxation/dysfunction may be the product of a given disorder rather than the cause, or it may exist as an independent disorder worthy of treatment and still not be directly related to the patient’s chief complaint. Pain in the somatic tissues is a frequent presenting symptom in acute conditions related to visceral dysfunction, and musculoskeletal manifestations of visceral disease are considered in many instances to be an integral part of the disease process, rather than just physical signs and symptoms.54

Clinical findings supportive of joint subluxation/dysfunction syndrome

Joint Assessment Procedures

The evaluation of primary joint subluxation/dysfunction is a formidable task complicated by the limited understanding of potential underlying pathomechanics and pathophysiologic conditions.55 In the early stages of primary joint subluxation/dysfunction, functional change or minor structural alteration may be the only measurable event. 56,57 Evident structural alteration is often not present, or none is measurable with current technology, and a singular gold standard for detecting primary joint subluxation/dysfunction does not currently exist. Therefore, the diagnosis is based primarily on the presenting symptoms and physical findings without direct confirmation by laboratory procedures.55

The physical procedures and findings conventionally associated with the detection of segmental joint subluxation/dysfunction (see Chapter 3 and Box 4-4) include pain, postural alterations, regional ROM alterations, intersegmental motion abnormalities, segmental pain provocation, altered or painful segmental end-range loading, segmental tissue texture changes, altered segmental muscle tone, and hyperesthesia and hypesthesia. Although radiographic evaluation is commonly applied in the evaluation for joint subluxation, it must be incorporated with physical assessment procedures to determine the clinical significance of suspected joint subluxation/dysfunction.

At what point specific physical measures are considered abnormal or indicative of joint dysfunction is controversial and a matter of ongoing investigation.58 The profession has speculated about the structural and functional characteristics of the optimal spine, but the degree of, or combination of, abnormal findings that are necessary to identify treatable joint dysfunction has not been confirmed.59 60 61 62 Professional consensus on the issue is further clouded by debates on how rigid a standard should be applied in the assessment of somatic and joint dysfunction and whether the standard should be set relative to optimal health or to the presence or absence of symptoms and disease. Until a professional standard of care is established, each practitioner must use reasonable and conservative clinical judgment in the management of subluxation/dysfunction. The decision to treat must be weighed against the presence or absence of pain and the degree of noted structural or functional deviation. Minor structural or functional alteration in the absence of a painful presentation may not warrant adjustive therapy.

The evaluation for and detection of joint restriction should not be the only means for determining the need for adjustive therapy. Patients with acute spinal or extremity pain may be incapable of withstanding the physical examination procedures necessary to definitively establish the nature of the suspected dysfunction, yet they may be suffering from a disorder that would benefit from chiropractic care. A patient with an acute joint sprain or capsulitis (facet syndrome, acute joint dysfunction) may have just such a condition, a disorder that limits the doctor’s ability to perform a certain physical examination and joint assessment procedures, yet is potentially responsive to adjustive treatment.63

The patient with an acute facet or dysfunction syndrome typically has marked back pain and limited global movements. Radiographic evaluation is negative for disease and may or may not show segmental malalignment. The diagnostic impression is based on location and quality of palpatory pain, the patient’s guarded posture, global movement restrictions and preferences, and elimination of other conditions that could account for a similar presentation.63 The physical findings that are often associated with the presence of local joint dysfunction, painful and restricted segmental motion palpation, and end feel are likely to be nonperformable because of pain and guarding.

Outcome Measures

Patient-oriented outcome measures (OMs) are procedures used to measure a patient’s clinical status and response to treatment. In the management of NMS conditions, this commonly incorporates measures that assess the patient’s pain symptoms, function (impairment), disability (activity intolerance), and general health status (Box 4-5).64,65

In the absence of definitive physical measures for the identification of manipulable spinal lesions, patient-oriented OMs provide a valid tool for measuring patient response to chiropractic treatment. The NMS disorders commonly treated by chiropractors are symptomatic or have a significant effect on the patient’s ability to function, establishing the patient as an excellent candidate for functional outcome assessment. 55,64,66

OMs do not necessarily represent the pathophysiologic status of the condition being treated. Instead, they answer questions about the quality or the perception of the patient’s life in comparison to the preillness state. OMs that evaluate functional status typically allow the assessment of multiple dimensions of patient functioning (e.g., physical and psychosocial). Many have well-demonstrated reliability and validity and stand as appropriate measures for monitoring the patient’s response to treatment.64 As such, they can be used to decide if a specific approach to dealing with patient complaints is effective and efficient compared with other approaches. It is the use of reliable and valid OMs in clinical studies and practices that will help quell the critical echoes of unscientific claims.

OMs incorporate self-reporting instruments and physical assessment procedures. Self-reporting instruments generally take the form of questionnaires that are used to quantify the degree of pain or the severity of disability as a result of impairment. Examples of tools that measure pain symptoms include the visual analog scale, which measures and rates a patient’s pain intensity and response to treatment; pain drawings, which identify the location and quality of pain; and the McGill pain questionnaire, which measures sensory, cognitive, and motivational elements of pain. Pain intensity can also be evaluated through palpation or with algometry. Palpatory assessment and location of pain have consistently demonstrated excellent reliability (see Chapter 3).

The patient’s perception of disability or activity intolerance is commonly measured by any of a number of self-reporting instruments. The Oswestry Disability Questionnaire67 and the Roland-Morris Questionnaire68 are common instruments applied in LBP disorders. The Neck Disability Index69 has been developed and applied for assessing disability associated with neck pain. Other measures that may be incorporated include evaluation of general health and well-being (e.g., Sickness Impact Profile, SF 36, EuroQol, and COOP Charts) and patient satisfaction surveys.65

The measurement of physical capacity for selected regional muscles and joints can be evaluated by a variety of physical tasks that measure ROM, muscle strength, and endurance. Normative values have been established for such procedures and can be effectively and economically used to monitor treatment progress.70 Four low-tech tests have been studied and have shown good reliability and correlation with spinal pain and disability (Box 4-6).71 Broader functional capacity or whole-body movement testing can also be measured. Testing in this arena is more complicated and time consuming. Functional capacity testing is often designed to simulate specific workplace demands and includes such procedures as “lifting, carrying, and aerobic capacity, static positional tolerance, balancing, and hand function.”64

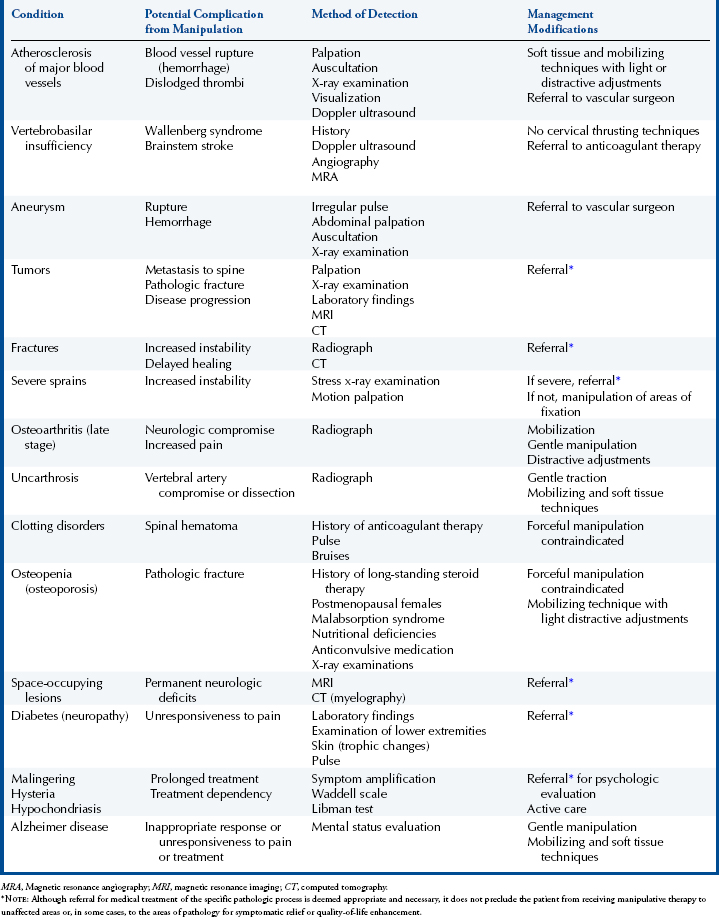

Contraindications to and complications of adjustive therapy

Manual therapy is contraindicated when the procedure may produce an injury, worsen an associated disorder, or delay appropriate curative or life-saving treatment. Although certain conditions may contraindicate thrusting forms of manual therapy, they may not prohibit other forms of manual therapy or adjustments to other areas.72,73

When manual therapy is not the sole method of care, it may still be appropriate and valuable in the patient’s overall health management and quality of life. For example, manual therapy, if not contraindicated, may help a cancer patient gain some significant pain relief and an improved sense of well-being. “Such palliative care should be rendered concomitantly and in consultation with the physician in charge of treating the malignancy.”72

Serious injuries resulting from adjustive therapy are very uncommon.74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 Suitable adjustive therapy is less frequently associated with iatrogenic complications than many other common health care procedures.83 The majority of spinal manipulation complications arise from misdiagnosis or improper technique. In the majority of situations, it is likely that injury can be avoided by sound diagnostic assessment and awareness of the complications and contraindications to manipulative therapy. Conditions that contraindicate or require modification to spinal manipulation are listed in Table 4-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree