Preparticipation Screening

James L. Moeller

Douglas B. McKeag

Initial Considerations

Performance of the preparticipation physical examination (PPPE) has been part of the primary care physician’s armamentarium for years. As more people participate in exercise and conditioning programs, the consistent advice from the medical establishment is “confirm your state of physical fitness before beginning an exercise program.” That advice carries with it an unspoken implication that the PPPE should at least assess risk of injury or harm from anticipated exercise. Some say these evaluations are merely a specialized health screening and argue about what should constitute the PPPE. At the very least, consistency is of utmost importance. The examination should assess risk factors and detect disease/injury that might cause problems during subsequent physical activity. Once past this generalized goal, disagreement arises from the different philosophical and medical viewpoints. The purpose of this chapter is to outline what should be determined and assessed, and how, when, and where such an examination should be conducted. It will not address the question of whether PPPEs are worthwhile.

The American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Sports Medicine, American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, and American Osteopathic Academy of Sports Medicine published a joint monograph outlining the PPPE in 1992 and which they updated in 1997 and again in 2005 (1,2). The PPPE outlined in this monograph is currently considered the standard for school-aged and young adult competitive athletes. Recommendations for the older athlete are less clear. Perhaps the most important point to remember regarding the PPPE is that it does NOT take the place of a comprehensive physical and health appraisal examination (CPE) in any age-group.

Essentials

By nature, any exercise evaluation of an individual should involve an awareness of the stress the exercise places upon three major body systems—musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and psychological. It is logical to emphasize these areas in the PPPE. The major question is, “Will this individual be at any greater risk of injury or illness given the anticipated exercise program?” Any evaluation should include clearly defined objectives (see Table 5.1). Failure to meet these objectives will do both the athlete and the physician a disservice. A final note: the number of PPPEs must not compromise the principles of efficacy and cost effectiveness.

Different situations and settings call for different types of evaluation. Flexibility in changing the PPPE is implicit in any of the subsequent recommendations in this chapter. The PPPE should also meet community and individual needs. Although there is no “right” way to perform the PPPE, the physician should look at who the prospective athletes are, what the contemplated exercise program is, and what the motivation to participate is.

Prospective Athlete

Understanding the characteristics of the target population is essential in determining what is assessed. One way to develop an appropriate PPPE is to look at prospective athletes by maturational age.

TABLE 5.1 Objectives of The Preparticipation Physical Examination | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Prepubescent Athlete (Approximate Age Range: 6–10 Years)

Youngsters have always been involved in spontaneous play but there is a trend toward increased organization. One consideration with this age-group is the manifestation of previously undiagnosed congenital abnormalities. Physicians should be well acquainted with all the common abnormalities of the age-group. The psychological makeup of young athletes is also important. At this age, the philosophy of the program the candidate is anticipating joining can be a major factor in predicting possible poor outcomes. The most common reasons for youth non-participation in sports (including those who started and stopped, as well as those who never began) in order of prevalence are (a) not getting to play, (b) negative reinforcement, (c) mismatching (d) psychological stress, (e) failure, and (f) overorganization. When asked about sports participation, 95% of youngsters felt the most important thing about sports was having fun, not winning (3) and recent reports note that up to 90% of children involved in sports would rather play on a losing team than sit on the bench on a winning team (4). Generally, this population is very healthy. The physician can exert a great deal of influence in the patient’s education aspects because habits have not been established. For instance, after correct methods of warm-up and cool-down are explained, a high degree of compliance can be expected.

Pubescent Athlete (11–15 Years)

These athletes are undergoing rapid body growth and change with the advent of physical, psychological, and sexual maturation. This group will have many non–exercise-related concerns (sexual activity, drugs). Given the appropriate examination format (see “Implementation” in this chapter), most of their questions can be addressed. If ever there is a time to expand a focused screening examination, it would be in this age-group. Most participating athletes at this age are involved in organized sports activities. The effect of exercise on human maturation directly relates to them.

Postpubescent/Young Adult Athlete (16–30 Years)

This group includes athletes with many reasons for exercising. Most elite athletes in the country are in this age-group, and it is also the age where most recreational athletes continue to compete. The PPPE needs to take into account the athlete’s skill level. Most of these athletes begin in organized sports and then become more involved in recreational and individual sports as they grow older. Important points to take into account when formulating the PPPE for this age-group include the past medical history (especially as it concerns previous injuries), and the need to make the examination sport-specific.

Adults (31–65 Years)

Most adults participate primarily in informal recreational sports. They may be categorized into roughly two types, the sporadic and the regularly exercising athlete. Participation of the first type is organized around team-oriented sports (softball, basketball) that are played or practiced one or two times during the week. Such an individual is prone to acute injury and should be informed of the importance of proper warm-up before participation. The regularly exercising athlete may participate in an individual or paired sport such as running, swimming, cycling, or racket sports. These individuals are more apt to suffer overuse syndromes and need to have the necessity for true exercise prescription stressed to them. This group of athletes rarely participates in any type of pre-exercise evaluation and usually surfaces for evaluation only after an injury has occurred. Yet, from a motivational standpoint, they tend to be the most adamant about their athletic participation, resulting in prevention or illness of disease. In this age-group, a CPE is recommended instead of a screening PPPE.

Elderly (66 Years and Older)

Exercise in the “old elderly” has been shown to lead to improved sense of well-being, postpone disability and increase the duration of independent living (5). Many

elderly individuals enter exercise programs as a result of the well-recognized rehabilitation potential of exercise after a serious injury or illness. Exercise is now a major part of the therapeutic regimen for many injuries and illnesses such as myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass, diabetes mellitus, asthma, and depression. These individuals often wish to continue exercising after their rehabilitation has ended. In most cases, the PPPE should merely be a part of the CPE called for in this age-group. The CPE is beyond the scope of this chapter, so when discussing this age-group we will only mention areas of the evaluation specific to athletic participation.

elderly individuals enter exercise programs as a result of the well-recognized rehabilitation potential of exercise after a serious injury or illness. Exercise is now a major part of the therapeutic regimen for many injuries and illnesses such as myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass, diabetes mellitus, asthma, and depression. These individuals often wish to continue exercising after their rehabilitation has ended. In most cases, the PPPE should merely be a part of the CPE called for in this age-group. The CPE is beyond the scope of this chapter, so when discussing this age-group we will only mention areas of the evaluation specific to athletic participation.

Contemplated Exercise Program

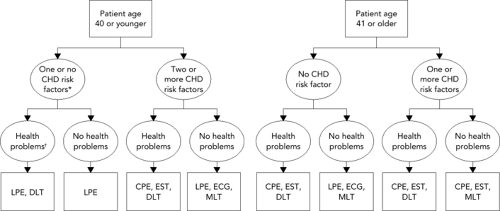

Not all exercises are the same. Depending upon the kind of exercise anticipated or wanted and what is discovered on the PPPE, several assessment options can be considered. There are three major types of exercise, aerobic, anaerobic, and combined (for an explanation of aerobic and anaerobic energy systems, see Chapter 3). Examples of aerobic exercise include repetitive endurance-type sports such as swimming, running, or biking. Examples of anaerobic exercise include sprinting and weight lifting. Most exercise tends to combine aerobic/anaerobic systems. Examples are soccer and basketball. Figure 5.1 portrays the type of office work-up that should be considered depending upon the patient’s age and general health status.

Motivation

Performing a PPPE begs the question, “why do you want to exercise?” Assessment of motivation is an extremely important part of the physical examination. In a prepubescent athlete, the answer may determine what comprises the remainder of the examination. In an adult athlete, overmotivation may predispose and predict future overuse problems. There are four major reasons (6) commonly given by older recreational athletes as their motivation to exercise:

Becoming healthy and gaining a feeling of self-satisfaction

Fear of dying

For the social components of exercise

As a part of a therapeutic regimen for illness or injury

Implementation

Formal, organized programs at any age (usually high school or college) involve enough athletes to warrant screenings. Conversely, physicians dealing with the informal recreational athlete should do so on an individual basis only. However, the objectives of the evaluations are similar, if not the same.

Implementation of the examination involves either the office-based or the station-based PPPE. The advantages and disadvantages of these PPPE formats are listed in Table 5.2. The required and optional components of the station-based PPPE are listed in Table 5.3. The locker room examination is still carried out in some instances but is not recommended. In this situation, one physician performs all aspects of each physical examination, usually in cramped quarters. There is little-to-no privacy for the individual athlete. It is done under rushed and noisy conditions and usually fails to address important questions.

TABLE 5.2 Advantages and Disadvantages to Office-Based and Station-Based Preparticipation Physical Examination Formats | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

TABLE 5.3 Required and Optional Components of Station-Based Preparticipation Physical Examination | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Frequency

Many clinicians advocate the traditional yearly sports examination, and annual PPPEs for interscholastic sport participation are required by most States. Some consider evaluation necessary before each sport season (7). Most sports medicine physicians favor doing an examination before the beginning of any new level of competition in an athlete’s career. For youngsters, this usually corresponds to school levels (grade school, junior high, high school, and college). We advocate an initial full-scale PPPE at the entrance to the particular level of participation, then the use of an intercurrent (or interval) review before the start of each sport season. This intercurrent review would include a full history and limited physical examination as directed by the history. It would allow for follow-up on rehabilitation of injuries incurred during the previous season or previous sport. Appendix 5.1 is a sample PPPE form that can be used for either the initial or intercurrent examination. For an intercurrent evaluation, the examining physician need only document the pertinent physical examination findings.

Basically, the optimal frequency of the PPPE has not been clearly established. Factors to consider when deciding on the frequency of PPPEs include (a) requirements of the school or the State, (b) cost to the athlete or family, (c) degree of risk of the sport, and (d) availability of qualified personnel.

It is important to keep two very important factors in mind: the age of the athlete in question, and the goals of the examination. Recommendations for each age-group are as follows:

Prepubescent. Initial examination should be done by the child’s primary care practitioner (PCP) in the office setting. This first sports physical examination is most important because it may represent the first interaction the child has had with the health care system for perhaps 2 to 5 years. Follow-up intercurrent examinations should be held on a yearly basis with attention to vital signs, injuries incurred since the last examination, maturation and development, and the wearing of any new appliances (glasses, contact lenses, bridges).

Pubescent/postpubescent. The initial PPPE can be done with either the office-based or station-based technique. One screening examination for junior high school, high school, and college should be performed. Intercurrent examinations should focus on vital signs, observation for completion of physical development, recent injury, and non–sports-related health concerns (e.g., drug use, eating habits, sexual history).

Adult (recreational). Any adult 40 years of age or younger should undergo a physical evaluation by his/her PCP before beginning any exercise program of more than low intensity. Annual CPEs have otherwise become a thing of the past for healthy, asymptomatic adults. There is no evidence that a screening CPE in this population is needed. Periodic health evaluations have been shown to improve the delivery/receipt of specific, important screening tests, although they have not been shown to improve short-term or long-term clinical outcomes, nor do they affect long-term economic outcomes (8). Despite this, approximately two third of physicians feel that the annual CPE in this population is necessary, has proven benefit, and detects subclinical illness. Approximately 90% of PCPs routinely perform screening CPEs on asymptomatic adults (9). Any adult 40 years or older should have a periodic health evaluation to assist in delivery of proven preventive measures such as pap smears, cholesterol screening, and fecal occult blood testing. The timing of these evaluations should be based on age, gender, and disease risk and do not have to be part of a head-to-toe examination. This advice is independent of whether the person is an athlete. Cardiac stress testing should be considered for certain patients based on risk assessment for underlying cardiovascular disease as outlined by American College of Sports Medicine recommendations (see Table 5.4) (10). Recommendations vary based on age of the patient, intensity of the proposed exercise, and the presence/absence of cardiac risk factors.

TABLE 5.4 Risk Assessment Criteria for Consideration of Graded Exercise Testing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Timing

Only one principle should dictate the timing of the PPPE. Examinations should occur before a particular sport season with enough time to allow for adequate rehabilitation of injury, muscle imbalances, and other correctable problems, but not so far ahead as to make the passage of time an important factor in the development of new problems. Most sports medicine physicians recommend that the

examination be performed approximately 6 weeks before the first preseason practice. If a longer time is taken, especially with the younger athlete, such factors as maturation and new injuries can decrease the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of the examination and decrease its preventive aspects.

examination be performed approximately 6 weeks before the first preseason practice. If a longer time is taken, especially with the younger athlete, such factors as maturation and new injuries can decrease the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of the examination and decrease its preventive aspects.

Content

History

A thorough history is the cornerstone of all medical evaluations. It is clearly the most sensitive and specific part of the PPPE process. Forms are preferable for a PPPE to insure that all essential information has been captured across various examiners. No one form could or should be advocated as being totally appropriate for a particular sports medicine program. However, recommended characteristics of that form can be found in Appendix 5.1. Any history form should be easy to complete, short (limited to one side of a piece of paper), self-administered, time efficient, and contain lay language easily understood by the athlete. Important highlights of any history include the following:

Cardiovascular system history. Used to rule out life-threatening cardiac abnormalities (e.g., hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [HCM], aberrant coronary arteries, arrhythmias). Table 5.5 lists the most common causes of nontraumatic sports death in high school and college athletes, and most causes are cardiac (11), highlighting the importance of the cardiovascular system history. Specific questions should include the following:

Have you ever passed out or nearly passed out during or after exercise?

Have you ever had chest pain, discomfort or pressure during exercise?

Have you ever had racing of your heart or skipped heartbeats during exercise?

Have you had high blood pressure or high cholesterol?

Have you ever been told that you have a heart murmur or heart infection?

Has a doctor ever ordered a test for your heart (e.g., echocardiogram)?

Has anyone in your family died for no apparent reason?

Does anyone in your family have a heart problem?

Has any member of your family died from of heart problems before the age of 50?

Does anyone in your family have Marfan syndrome?

TABLE 5.5 Most Common Causes of Nontraumatic Sports Death in High School and College-Aged Athletes

Nontraumatic Sports Deaths

Total (n = 136)

Male (n = 124)

Female (n = 12)

Athletes with cardiovascular conditions

100

92

8

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

51

50

1

Probable HCM

5

5

0

Coronary artery anomaly

16

14

2

Myocarditis

7

7

0

Aortic stenosis

6

6

0

Dilated cardiomyopathy

5

5

0

Atherosclerotic coronary disease

3

2

1

Aortic rupture

2

2

0

Cardiomyopathy-NOS

2

2

0

Tunnel subaortic stenosis

2

2

0

Coronary artery aneurysm

1

0

1

Mitral valve prolapse

1

1

0

Right ventricular cardiomyopathy

1

0

1

Ruptured cerebellar AVM

1

0

1

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

1

0

1

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

1

1

0

Athletes without cardiovascular conditions

30

27

3

Hyperthermia

13

12

1

Rhabdomyolysis and sickle trait

7

6

1

Status asthmaticus

4

3

1

Electrocution due to lightning

3

3

0

Arnold-Chiari II malformation

1

1

0

Aspiration-blood-GI bleed

1

1

0

Exercise-induced anaphylaxis

1

1

0

Athletes with cause of death undetermined

7

6

1

HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; NOS =; AVM = arteriovenous malformation; GI = gastrointestinal. From van Camp et al. (11)

A positive answer to any of these questions should raise a red flag to the possibility of a cardiac condition that could lead to sudden cardiac death. The presence of dizziness during or after exercise used to be considered a red-flag finding; however, a positive history of dizziness has low sensitivity and specificity for underlying cardiac disease.

Neurological system history. Used to assess the risk of recurrent or potentially permanent neurological injury. Questions should include the following:

Have you ever had a head injury or concussion?

Have you ever been hit in the head and been confused or lost your memory?

Have you ever been knocked out or become unconscious?

Have you ever had a seizure?

Do you have headaches with exercise?

Have you ever had numbness or tingling in your arms or legs after being hit or falling?

Have you ever been unable to move your arms or legs after being hit or falling?

Have you ever had a stinger, burner, or pinched nerve?

A complete history of head trauma resulting from athletic competition is important to have when qualifying a potential athlete for a contact or collision sport. It is important to note and monitor cumulative, subtle, neurological loss of function. Athletes with a history of poorly controlled seizures should be disqualified from high-risk sports. A history of recurrent upper extremity paresthesias from contact sports may indicate the presence of cervical canal stenosis, an entity that puts an athlete at risk for permanent neurological injury.

Respiratory system history. Used primarily to identify exercise-induced bronchospasm. Questions include the following:

Do you cough, wheeze, or have trouble breathing during or after activity?

Has a doctor ever told you that you have asthma or allergies?

Is there anyone in your family who has asthma?

Have you ever used an inhaler or taken asthma medicine?

Musculoskeletal system history. Important questions include the following:

Have you ever had an injury such as a sprain, muscle or ligament tear, or tendinitis, which caused you to miss a practice or game?

Have you broken or fractured any bones or dislocated any joints?

Have you ever had a stress fracture?

Have you ever had a bone or joint injury that required x-rays, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography scan, surgery, injections, rehabilitation, physical therapy, a brace, a cast, or crutches?

Have you ever been told that you have or have you had an x-ray for neck instability?

Do you regularly use a brace or assistive device?

Past medical history. This should elicit information about chronic illnesses as well as any condition that may have led to limited sport participation or disqualification from participation. Questions should include inquiries regarding prior hospitalizations and surgeries. Responses to these questions may also explain functional abnormalities such as muscle imbalance, decreased respiratory volume, or below-normal exercise tolerance.

Medications, drugs, and supplements. The effect of medications and drugs on the exercising body can be serious. It is vital knowledge if an individual is injured or rendered unconscious. Otherwise, appropriate steps to treat an injured or ill athlete cannot be taken. Over-the-counter supplements (e.g., creatine) are used by many athletes of all ages for the purpose of performance enhancement. These substances are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and may contain a variety of other substances. There are anecdotal reports of various injuries associated with supplement use. Questions regarding medications should include prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs and supplements.

Allergies. Common occurrences, such as allergies to bee stings, medications, foods, and other environmental substances need to be known so that prophylactic measures can be taken in case of exposure.

Appliance use. Information about mouth, eye, or ear appliances should be known in case an athlete is injured or unconscious. Such appliances can hinder resuscitation.

Heat illness history. Used to assess the risk of recurrent heat illness.

Menstrual history. Absence of menses may place young women at risk for fractures due to traumas or falls, or for stress fracture. Absence of menses may also be a red-flag sign of the female athlete triad.

Additional history. Other important areas of history include vision history, the loss or congenital absence of a paired organ, prior history of infectious mononucleosis, and a prior history of contagious skin lesions (particularly important in mat sport athletes). Questions regarding the history or family history of sickle trait and sickle cell disease should also be included. Nutritional history is very important, and may help to identify athletes at risk for developing eating disorders.

TABLE 5.6 Physical Examination Emphasis

Sport

Areas to Assess

Baseball

Shoulder, elbow, arm

Basketball

Ankles, knees

Football

Neck, head, knees, low back (linemen)

Gymnastics

Wrists, shoulders, low back

Handball

Wrist, hand, elbow, shoulder

Running

Back, hips, knees, ankles, feet

Soccer

Hips, pelvis, knee, feet

Swimming

Ears, nose, throat, shoulders

Wrestling

Body fat (%), neck, shoulders, skin

“Are there any questions you’d like to ask the physician?” This question allows the athlete to ask any question about any body system. The authors feel that the addition of this question to the PPPE history is very important.

Physical Examination

Whenever possible, a sport-specific physical examination, emphasizing those areas where injury and/or illness have the greatest epidemiological occurrence, is a primary goal (McKeag, 1985). Any examination assessing a sports candidate without an awareness of the demands of their specific sport suffers a major weakness (see Table 5.6).

Evaluation of a swimmer should be different from that of a football player. Regardless of age, sex, or situation, three areas of the PPPE should always be emphasized:

Cardiovascular system (including blood pressure determination)

Musculoskeletal system (including range of motion and strength assessment)

Psychological assessment (including motivation for exercise)

Because the prevalence of disqualifying conditions is so low among athletes and because few of these patients produce significant physical findings, the yield from the physical examination is very low (Runyan, 1983). The existing community sports medicine network, and specifically the office-based sports medicine practitioner, should take the time to study what is needed in the local environment.

Standard components of the physical examination should include the following:

Height and weight. Unusual variance in either of these vital signs should signal further investigation. Apart from some rare endocrine disorders, four common problems are:

Eating disorders—abnormal eating or weight loss patterns are often seen in sports requiring strict adherence or emphasis on body weight such as wrestling, women’s gymnastics, and cross-country or distance running.

Exogenous hormone consumption—ingestion/injection of ergogenic aids for increased strength and power or suppression of puberty is unfortunately not an uncommon occurrence.

Obesity—an athlete greater than 20% overweight for height, age, and stature has a relative cardiac and general health risk. Referral for dietary counseling is advised.

Late maturation—occurring naturally or secondary to poor nutrition, delayed maturation can affect both height and weight measurements. Strenuous exercise before puberty may delay the maturation process.

Vital signs

Blood pressure must be measured with a proper sized cuff to reduce the likelihood of false elevation or false reduction of blood pressure. Remember that in children, acceptable blood pressure varies with age, gender, and height (12) (see Table 5.7A and B). Many athletes weight train as part of their preseason training program. Sustained isometric activity (improper weight lifting) causes a marked and sometimes prolonged elevation in blood pressure that may lead to elevated blood pressure on the PPPE. Hypertension in the young athlete population should prompt consideration of secondary causes.

Pulse should be obtained at the radial and femoral arteries. Radial artery pulse is adequate to determine heart rate and regularity. A nonpalpable, delayed, or reduced strength femoral pulse should raise the suspicion of coarctation of the aorta.

Eyes

Visual acuity—the Snellen eye chart can be used to test correctable vision to better than 20/200. Such emphasis is necessary for detection of legal blindness, a major basis for disqualification, and impaired vision, a major factor in poor performance. Visual acuity should be 20/40 or better (with or without corrective lenses) in each eye.

Pupils—pupil size is evaluated to look for anisocoria (unequal pupil size). The presence of anisocoria needs to be carefully documented and communicated to the athlete, parents, athletic trainer, and coach so the baseline difference is understood in the event of head injury. Pupillary response to direct and consensual light exposure is also evaluated.

Ears, nose, and throat. This portion of the PPPE is performed to document the general status of these areas.

Cardiovascular examination. Major emphasis in this area is necessary in any athletic screening examination. Sudden death in healthy athletes is uncommon but does occur and the primary mechanism usually

involves the cardiovascular system. The catastrophe is almost always totally unexpected, all the more tragic and alarming. Most young athletes suffering sudden death have underlying cardiovascular disease (Maron et al., 1986). The following important points about the cardiovascular examination should be remembered:

Murmurs

A normal, “functional” heart murmur may be audible in any child sometime during development.

Murmur intensity does not always correlate with the significance of the murmur.

The differential diagnosis of normal murmurs in young athletes, as outlined by Strong and Steed (1984), should be familiar to the examiner.

The following guidelines to listening to heart murmurs in athletes are helpful:

If the S1 can be heard easily, the murmur is not holosystolic—therefore ventricular septal defect (VSD) and mitral insufficiency can be ruled out.

If S2 is normal—Tetralogy of Fallot, atrial septal defect (ASD), and pulmonary hypertension are ruled out.

If there is no ejection click—aortic and pulmonary stenosis can be excluded.

If a continuous diastolic murmur is absent—patent ductus arteriosus is not present.

If no early diastolic decrescendo murmur exists—aortic insufficiency can be ruled out.

TABLE 5.7A Blood Pressure Levels for Boys by Age and Height Percentile

Systolic BP (mm Hg)

Diastolic BP (mm Hg)

← Percentile of Height →

← Percentile of Height →

Age (Year)

BP Percentile ↓

5th

10th

25th

50th

75th

90th

95th

5th

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access