Posture

Timothy L. Kauffman and Michelle A. Bolton

Introduction

Posture is the alignment of body parts in relationship to one another at any given moment. Posture involves complex interactions between bones, joints, connective tissue, skeletal muscles and the nervous system, both central and peripheral. The complexity of these interactions is compounded when one considers the near infinitesimal variety of human balance, motor control and movement in relation to gravity. Furthermore, with the passage of time, each organism undergoes change resulting from microtrauma, frank injuries and the effects of disease on the neuromusculoskeletal system which result in the common and unique variations of aging posture.

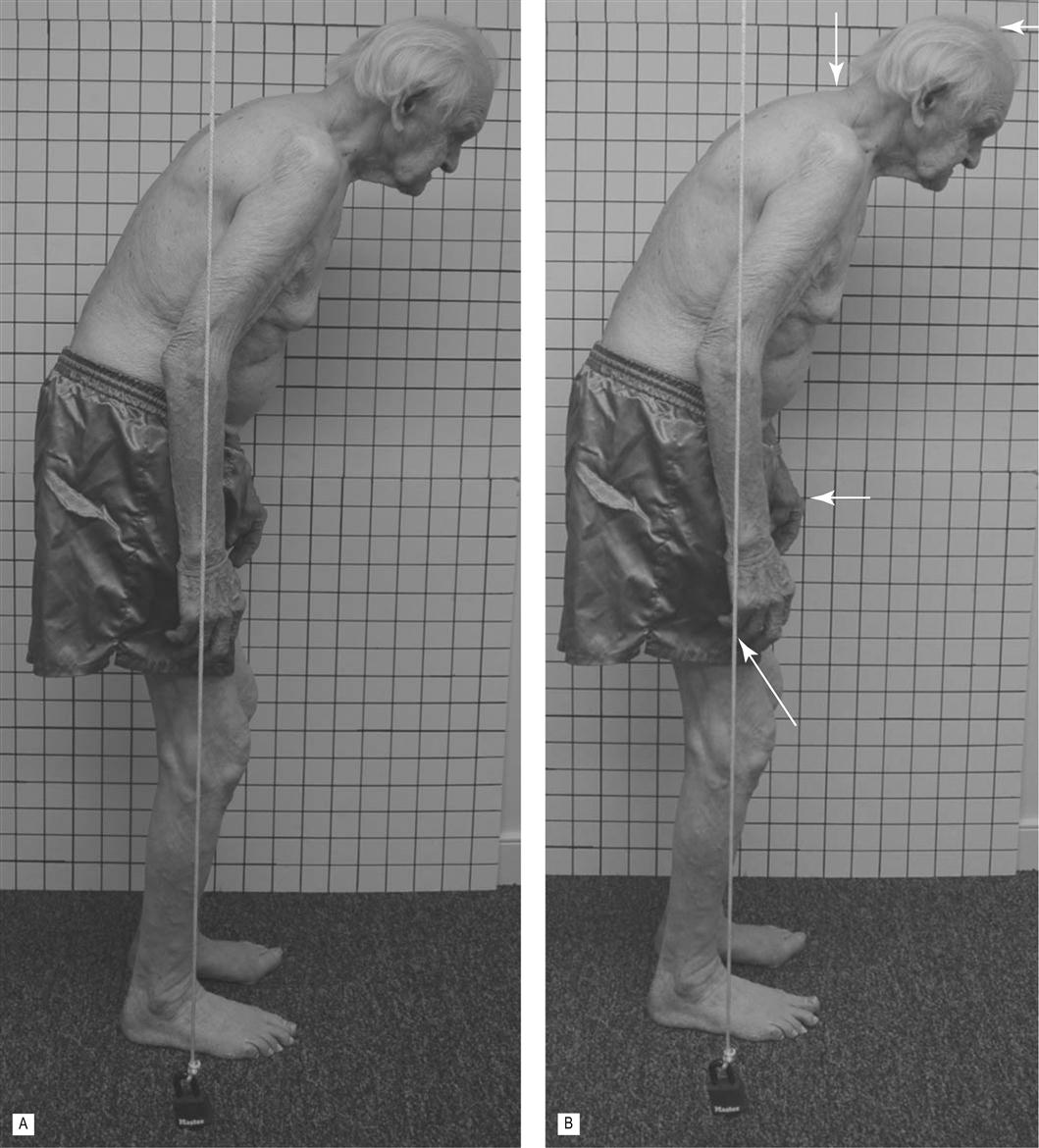

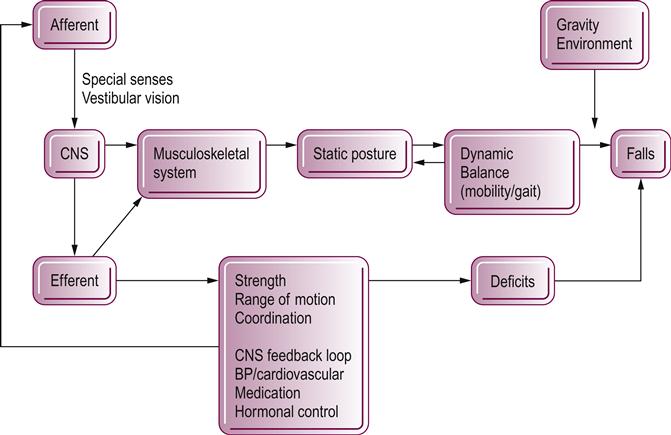

Posture is commonly assessed using a grid or plumb line, with the patient in a static standing position; however, within the aging population, this becomes more difficult because of the age-associated increase in postural sway. This can be seen in the two photos in Figure 15.1 of a 98-year-old man taken only moments apart. The postural control mechanisms produce minor shifts in weight in order to avoid fatigue, excessive tissue compression and venous stasis. Hence, a photographic assessment of posture represents a fixed instant of a postural set. Thus, posture is actually a relative condition requiring full body integration and both static and dynamic balance control, as shown in Figure 15.2.

Multiple factors are involved in common age-related postural changes. These factors may be pathological, degenerative or traumatic, or may result from primary musculoskeletal changes, primary neurological changes or a combination of diminutions in the neuromusculoskeletal system.

Degenerative joint disease is a common age-related pathology involving bony and joint surface changes (see Chapters 19 and 24). The osteophytes that result from arthritis may prevent normal joint motion, cause pain and possibly encroach on nerves with a subsequent radiculopathy that includes muscle weakness and imbalance. Postural adjustments may be the result of attempts to unload weight from an osteophyte in order to reduce pain or to accommodate a radiculopathy.

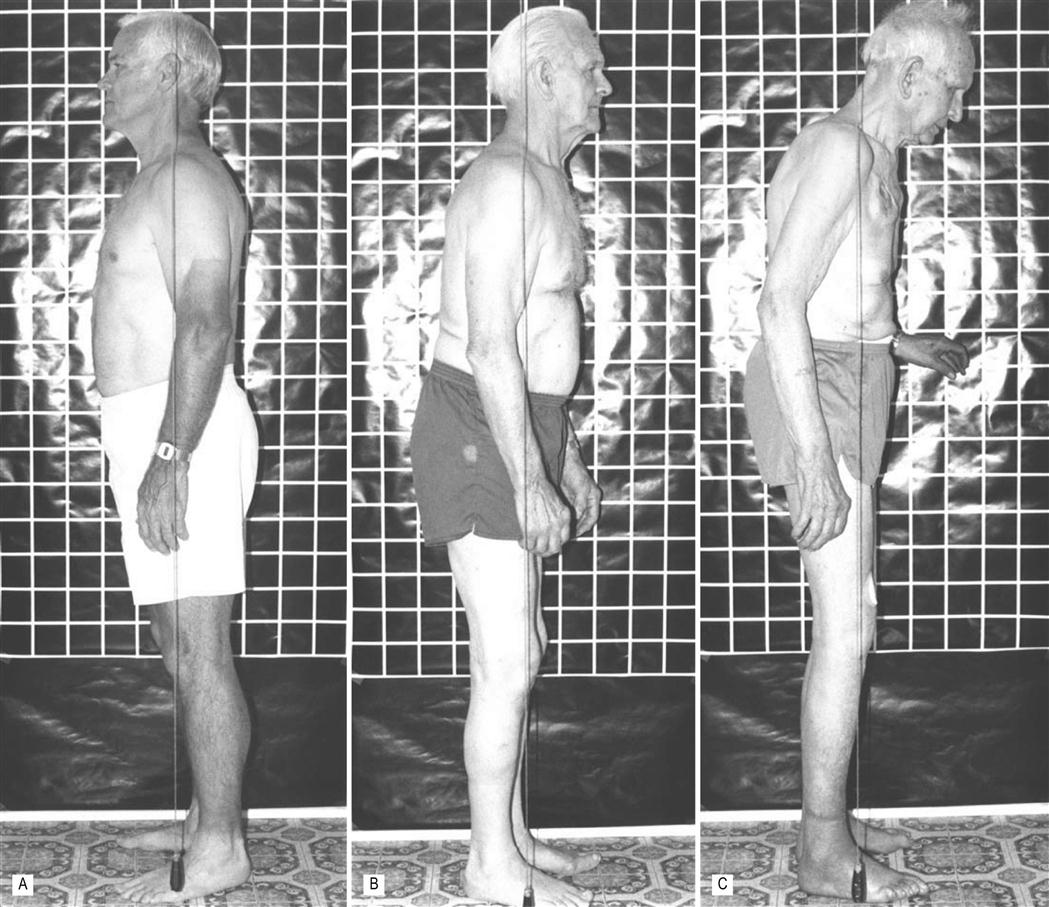

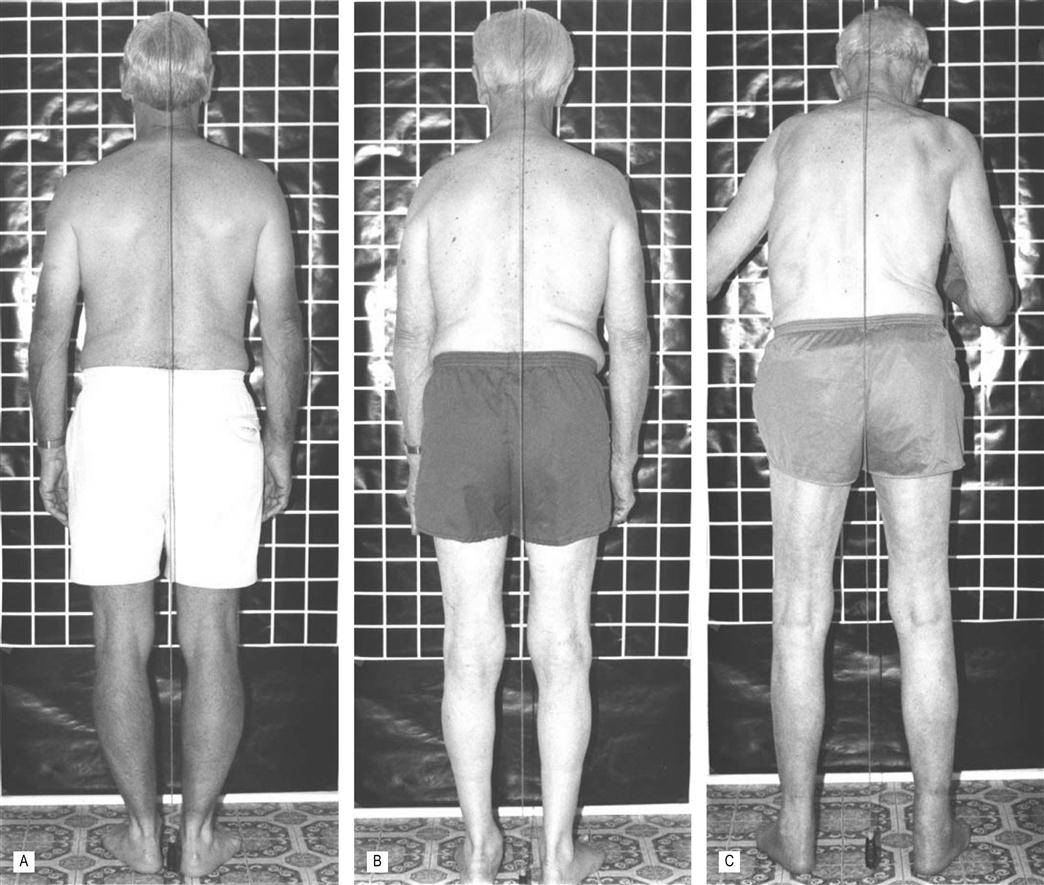

Axial and appendicular skeletal changes

The common age-associated postural changes in the axial skeleton and their clinical implications are enumerated in Table 15.1 and may be seen in Figures 15.3 and 15.4. The idiosyncratic effects of 20 years of aging can be seen by comparing the images of the 78-year-old man in Figures 15.3B and 15.4B with the photographs in Figures 15.1 and 15.5, which were taken when the man was 98 years old. In the lateral view, note the large increases in trunk kyphosis and hip flexion. By comparing images of the posterior view at different ages (Fig. 15.4B and Fig. 15.5), the kyphoscoliosis with upper extremity extension, increased hip and knee flexion and loss of muscle mass in all four extremities and trunk are evident. A different individual, aged 93 years and shown in Figure 15.3C, also demonstrates extension of the upper extremities. The 98-year-old man’s postural set (Figs 15.1 and 15.5) may be affected by his complaints of right hip pain, and decreased sensation and strength in the lower extremities. He lives in assisted living and uses a wheeled walker for most ambulation.

Table 15.1

Age-associated postural axial skeletal changes and their clinical implications

| Axial Skeletal Changes | Clinical Implications |

| Head forward | Shifts center of mass forward; may increase dizziness because of a compromised basilar artery |

| Dorsal kyphosis | Reduces trunk motions for breathing and motor responses; encourages scapular protraction; may provoke shoulder pathologies |

| Flat lumbar spine | Reduces trunk/hip extension for gait strides |

| Occasional kyphosis of lumbar spine | Results from compression of vertebral bodies; not reversible |

| Increased lordosis (least common) | Results in tightness of trunk/hip extensors; weakened abdominals |

| Posterior pelvic tilt | Results from prolonged sitting; reduces trunk/hip extension for gait strides |

| Scoliosis | May alter balance, breathing and extremity motions |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree