Posterolateral Approach (Including Minimally Invasive Variations)

Muyibat A. Adelani

James I. Huddleston

INDICATIONS

Approaching the hip joint from a posterior direction was originally described by the German surgeon Bernard Von Langenbeck. Von Langenbeck’s approach was later modified by the Swiss surgeon Theodor Kocher, who used it mainly for the treatment of septic arthritis from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The posterior approach, as we know it today, was described by Austin T. Moore as the “low posterior approach” or “southern exposure,” because it was more inferior than the traditional posterolateral approach at that time (1). Historically, this approach was utilized by Moore and others for hip arthroplasty, arthrodesis, and osteotomies for congenital hip dislocations (1). The approach has been further modified for arthroplasty into what is commonly referred to as the “mini-posterior” approach that utilizes shorter skin and fascial incisions (6 to 10 cm) by eliminating the proximaland distal-most aspects of the standard posterior incision (2,3).

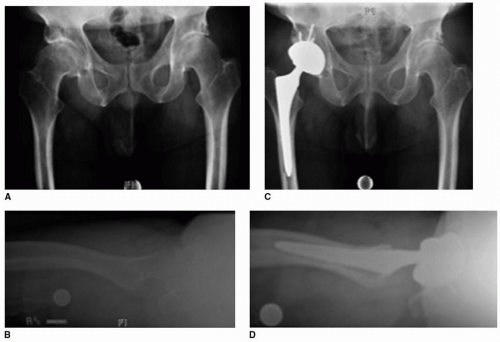

Currently, the posterior approach is most commonly used for primary (Fig. 3-1) and revision total hip arthroplasty, as well as hip hemiarthroplasty for fracture. A major advantage of this approach is that it is extensile. The standard approach, as used for arthroplasty, can be extended proximally into the Kocher-Langenbeck approach for fixation of the posterior wall of the acetabulum or the posterior column of the pelvis. It can be also extended distally to expose the femur to perform trochanteric osteotomies or to fix periprosthetic femur fractures. Although primary and revision hip arthroplasty may be performed through multiple different approaches, there are some scenarios in which a posterior approach may be preferred, that is, total hip replacement in cases requiring trochanteric osteotomy for exposure (the stiff or ankylosed hip) or for congenital hip dislocation requiring femoral shortening, revisions in which fixation of the posterior column is required or revisions of well-fixed femoral components requiring extended trochanteric osteotomy for removal.

Perhaps, the most important advantage of the posterior approach is that the abductor musculature is preserved (1). This results in a lesser incidence of postoperative limp in comparison to the anterolateral or direct lateral approaches (4,5). Further, the posterior approach can be performed without the need for special equipment, such as a fracture table or fluoroscopy, which makes it more cost-effective than some direct anterior approaches. Lastly, the posterior approach affords limited risk to damaging the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, which occurs often during the direct anterior approach (6).

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Use of the posterior approach is controversial in joint-preserving procedures requiring an arthrotomy, such as drainage of a septic hip, removal of a loose body, or fixation of a femoral head fracture due to concerns for disruption of the blood supply to the femoral head. The primary blood supply to the adult

femoral head courses posteriorly from branches of the medial femoral circumflex artery (7); therefore, a posterior capsulotomy could disrupt this and risk the development of osteonecrosis. In cases of arthroplasty, the posterior approach may be avoided by some surgeons in favor of other approaches in patients in whom the risk of dislocation is high, such as those with cognitive impairment, neuromuscular disorders, or those who are wheelchair-bound. However, this is only a relative contraindication, and hip arthroplasty can be successfully performed via the posterior approach in these clinical scenarios.

femoral head courses posteriorly from branches of the medial femoral circumflex artery (7); therefore, a posterior capsulotomy could disrupt this and risk the development of osteonecrosis. In cases of arthroplasty, the posterior approach may be avoided by some surgeons in favor of other approaches in patients in whom the risk of dislocation is high, such as those with cognitive impairment, neuromuscular disorders, or those who are wheelchair-bound. However, this is only a relative contraindication, and hip arthroplasty can be successfully performed via the posterior approach in these clinical scenarios.

TECHNIQUE

Positioning

After the anesthesia of choice is established, the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the operative side up. There are many different devices for lateral positioning, including peg boards, bean bags, and anterior and posterior pads. We use a peg board, placing pegs anteriorly on the pubis symphysis and posteriorly on the sacrum to stabilize the pelvis. We aim to have the posterior surface of the sacrum perpendicular to the floor and to minimize any cephalad or caudal tilt of the pelvis. An axillary roll is placed just inferior to the axilla. The torso is stabilized with an anterior peg at the distal sternum and a posterior peg at the same level. It is important to ensure that the torso and pelvis are stabilized in a neutral position, or even slightly tilted posteriorly, as the pelvis tends to fall forward once the hip is dislocated and the leg is held in an adducted position. Any excessive anterior or posterior tilt of the pelvis in the lateral position makes it more difficult to place the acetabular component in an appropriately anteverted position. Once the positioning is deemed acceptable, all bony prominences are padded. Padding is placed between the pegs and the patient, especially the proximal pegs. Padding or a gel pad is also placed beneath the nonoperative leg to protect the peroneal nerve. The nonoperative hip is flexed to approximately 45 degrees. While the exact amount of flexion is not critical, it is important to be consistent as hip flexion tends to flex the pelvis, which can influence the final acetabular component position. The dependent arm is placed in full extension on a well-padded arm board. The ulnar nerve must be

well-padded at the elbow. Two pillows are then placed between the dependent arm and the upper arm, which is then taped in place. Alternatively, a padded Mayo stand can be used as a rest for the upper arm.

well-padded at the elbow. Two pillows are then placed between the dependent arm and the upper arm, which is then taped in place. Alternatively, a padded Mayo stand can be used as a rest for the upper arm.

Draping

A nonsterile U-drape is used to isolate the surgical limb from the remainder of the body and define the surgical field. It is important that around the hip itself, this drape is placed as widely as possible, in order to allow the exposure to be extensile posteriorly, if necessary. The limb is sterilely prepped with ChloraPrep (3M, St. Paul, MN). In most cases, the foot is not prepped, as the leg is being held up by a candy cane leg holder. A sterile half sheet is used to cover the patient’s torso. An impervious sterile U-drape is placed on top of the previously placed nonsterile U-drape. A sterile stockinette is used to cover the leg to a level just above the knee. The leg is then wrapped with 6-inch Coban (3M, St. Paul, MN), a self-adherent wrap. A hip drape is placed. All exposed skin is then covered with Ioban (3M, St. Paul, MN), an iodine-impregnated adhesive skin barrier.

Surgical Technique

With the hip flexed to approximately 45 degrees, a curvilinear incision, centered at the tip of the greater trochanter, is made on the lateral aspect of the hip. The distal aspect of the incision is in line with the femoral shaft. The proximal aspect curves posteriorly from the tip of the greater trochanter toward the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). The length of the incision is highly dependent on the exposure needed for adequate visualization. It may vary due to the patient’s body habitus. In our hands, it is generally 15 cm or less in length (Video 3-1).

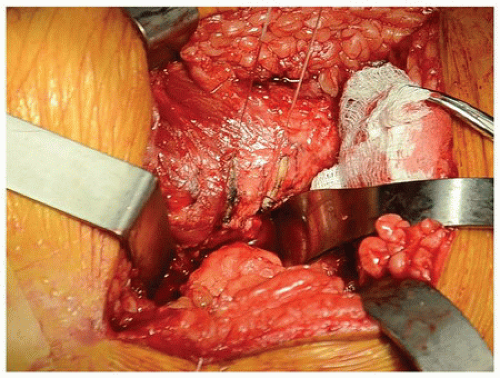

The skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised sharply down to the level of the fascia lata. A Cobb elevator is used to elevate the overlying adipose tissue from the fascia. The adipose tissue is peeled back just enough to facilitate the fascial incision. Excessive stripping of the adipose tissue may yield poor cosmetic results due to dimpling from fat necrosis. The fascia lata and gluteal fascia are then incised sharply in line with the incision. A plane between the gluteus maximus and the underlying abductors is developed bluntly. The gluteus maximus is manually split, and when resistance is encountered, dissection is paused to identify crossing blood vessels for cauterization. The sciatic nerve is identified. A Charnley retractor is placed beneath the gluteus maximus. The posterior aspect of the gluteus medius is identified and retracted gently anteriorly. Great care is taken to avoid rigorous retraction of the gluteus medius, as this may contribute to the formation of heterotopic ossification postoperatively. The piriformis tendon is identified, released from the trochanteric ridge, and tagged with a suture. The short external rotators (superior gemellus, obturator internus, and inferior gemellus) and quadratus femoris are then identified and elevated from the posterior aspect of the trochanter subperiosteally, using electrocautery. Some surgeons prefer to leave the quadratus femoris muscle intact. A plane is further developed between these muscles and the underlying posterior hip capsule using electrocautery. Further dissection around the inferior femoral neck is performed bluntly with a sponge. The inferior border of the gluteus minimus is identified and retracted gently with a Hibbs retractor. We avoid retracting this with a Cobra retractor, as this is usually unnecessary and may place the muscle under undue tension.

A trapezoidal capsulotomy is performed, and the capsule is tagged with two sutures at its proximal and distal points. Then, using these tagging sutures, the capsule is reduced to the intertrochanteric ridge, and the point where the edge of capsule meets the trochanter is marked with electrocautery, as an indicator of the patient’s native offset and limb length (Fig. 3-2). It is important to note that the limb must be in a similar position when these measurements are carried out after the reconstruction. Further,

fixed pins in the pelvis and greater trochanter can also be used to optimize limb length and offset. We prefer to use a jig on the inferior poles of the patellae as an additional reference point for limb length.

fixed pins in the pelvis and greater trochanter can also be used to optimize limb length and offset. We prefer to use a jig on the inferior poles of the patellae as an additional reference point for limb length.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|