Posterior Mini-Incision Aclr Hamstring Harvest

Chadwick Prodromos MD

Using the traditional anterior approach to perform the hamstring harvest for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) can be a difficult task, particularly in large or obese patients.

If the intertendinous cross connections are not completely divided prior to tendon stripping, the tendons can be cut too short to use necessitating a switch to autologous bone-tendon-bone (BTB) or a previously ordered allograft which is kept in reserve.

The posterior approach to the hamstring harvest brings these intertendinous cross connections, especially the accessory semitendinosus, into plain view of the surgeon, where they can be easily sectioned under direct vision prior to tendon stripping.

Additional benefits of the posterior approach are that it allows easier identification of the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons, improved cosmesis and reduced harvest time.

The hamstring harvest is generally acknowledged to be the most difficult part of hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) (1). It has traditionally been carried out through a 4 to 5 cm anterior approach. While surgeons performing large numbers of hamstring harvests become technically proficient using this traditional anterior approach, there are many surgeons who perform limited numbers of ACLRs [or who have recently switched from bone-tendon-bone (BTB) to hamstring] for whom the harvest can be daunting. Even the very best surgeons (2) acknowledge that the harvest is challenging in large and obese patients.

While it is seldom reported, it is not uncommon for the graft to be cut too short to use in clinical practice. This occurs when surgeons fail to cut tendinous cross connections prior to harvesting the tendon with the tendon stripper. The tendon stripper will then occasionally amputate the tendon itself at the point of the cross connection (rather than sectioning the cross connection), rendering the tendon too short to use. Because the cross connections often will be sectioned by the tendon stripper even if the surgeon does not cut them first, the surgeon may be lulled into a false sense of security that he doesn’t need to go to the additional trouble to visualize them and cut them before harvesting. However if this shortcut is taken a tendon will eventually be cut too short to use, necessitating a switch to autologous BTB or a previously ordered allograft kept in reserve for this eventuality.

The primary difficulty lies in visualizing these posteromedial tendinous cross attachments from the traditional anteromedial approach. These cross tendons, especially the accessory semitendinosus (ST), are not described in standard anatomy texts and may be unknown to some surgeons. The references describing the accessory ST (3,4,5) should be read by any surgeon planning to perform hamstring ACLR. It must also be realized that these cross connections are variably present, particularly regarding the gracilis (Gr), and the tendons must be adequately visualized to a distance of roughly ten centimeters from their insertion to make sure that all such cross connections are satisfactorily found and sectioned. While these cross connections can certainly be found from the anterior approach, they lie far enough posterior to the traditional anterior incision to render the process challenging in many patients—especially large patients. Attempts to blindly cut them can result in accidentally cutting the tendon itself or the saphenous nerve. However good visualization from the traditional anterior approach may require enlargement of the incision to a degree greater than the surgeon had led the patient to believe would be

used. Strong retraction can also damage the saphenous nerve, and this process can be quite time consuming.

used. Strong retraction can also damage the saphenous nerve, and this process can be quite time consuming.

Even if the cross connections are satisfactorily cut the tendon stripper can still occasionally become entangled in the semimembranosus sling more proximally during harvesting, cutting the tendon short at this level. Particularly in large patients, the surgeon’s index finger is usually not long enough to reach this area from the traditional anteromedial approach to free the tendon stripper.

Another problem with the traditional anterior approach is that the initial differentiation of the three pes tendons by this approach can be difficult. There are no reliable landmarks for finding the tendons anteriorly before making the incision (videos showing identification of the individual tendons by external tendon palpation always show patients with extremely low body fat). The traditional anteromedial approach puts the incision over the general area of the pes insertion. However at this point all three tendons are conjoined. Differentiation of the ST and Gr (or sartorius) therefore necessitates dissecting backward to identify the tendons proximal to their conjoined insertion where they are separate structures and then returning forward.

The posterior mini-incision approach to the harvest described below greatly facilitates the harvest primarily because it obeys a basic surgical principle that the traditional anteromedial principle violates, namely to put the incision where the dissection needs to be.

The posterior approach thus has four important advantages relative to the traditional anterior approach.

The posteromedial accessory semitendinosus and other cross connections are easier to see and section, thus preventing the tendon from being harvested too short to use.

The tendons are easier to identify as separate structures posteriorly.

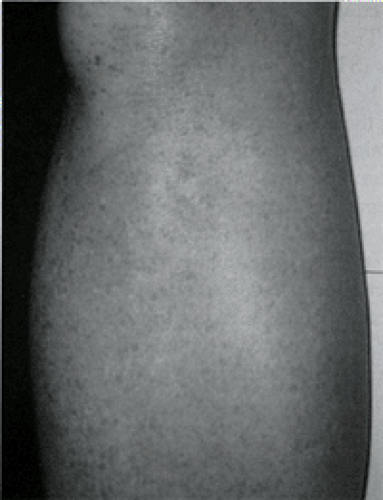

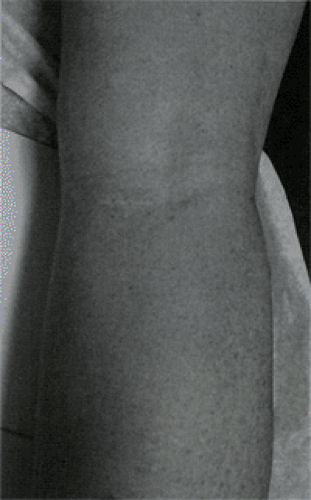

Fig 34.2-2. Picture of posterior mini-incision. Appearance of posterior mini-incision after healing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access