Chapter 110 Posterior Cruciate Sacrificing Total Knee Arthroplasty

Debate continues regarding the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) in total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Good long-term data exist both radiographically and clinically for PCL sparing and PCL substituting types of implants.7,20 Some surgeons routinely sacrifice the PCL, and others routinely spare the PCL. Some surgeons make an intraoperative decision based on intraoperative findings. National trends from the previous decade in which most knee arthroplasties were performed with PCL retaining–type implants have changed to a more recent trend of PCL substituting implants with a post and cam mechanism, or sacrificing and substituting with a highly conforming deep dish polyethylene.17

This author represents the group of surgeons who make an intraoperative decision to spare or sacrifice the PCL. The algorithm followed closely matches that suggested by Lombardi and associates.13 Initial attempts in straightforward TKA are to spare the PCL, with the exception of a few notable clinical situations. Significant initial malalignment greater than 15 degrees in varus or valgus or significant flexion contracture precludes the ability to sufficiently balance soft tissues and expose the joint with PCL retention.9,21 Inflammatory arthropathies are also known for late failure of PCL after initial retention.1,10 Prior patellectomy disrupts the normal kinematics of the knee and yields inferior results if PCL retention is chosen.15 Similarly, inferior results have been detected in prior high tibial osteotomy patients who do not have a PCL substituting implant.26

Sparing the PCL

Salvage of the PCL provides possible kinematic and proprioceptive benefits. However, concerns with regard to salvage of the PCL have been raised. The kinematic benefit of cruciate retaining arthroplasty appears to be absent on fluoroscopic analysis.25 One magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based study demonstrated that tibial bone cuts interrupted the PCL to a significant degree most of the time.24 Late failure of a retained PCL leading to revision is described as occurring in up to 2% of cases in one series.1,18 Histologically, the PCL is abnormal in a significant number of arthritic knees.19 These findings and others show why this author recommends protecting the PCL (Fig. 110-1) with an osteotome if it is to be saved, and proving its stability before selecting PCL retaining or substituting final components.

Sacrificing the PCL

Posterior Stabilized Polyethylene Prosthesis

The posterior stabilized condylar prosthesis was introduced in 1978 with specific goals of preventing tibial subluxation, improving range of motion, and improving stair-climbing ability.6 Design theory included lengthening the effective moment arm of the quadriceps by forcing the contact point of the femur more posterior, giving a mechanical advantage over previous designs.6 Long-term results are good with the posterior stabilized design, but specific clinical problems are associated with this design.

Patellar clunk syndrome was a significant problem with early designs of posterior stabilized TKA. The long intercondylar notch of the femoral cam and post mechanism allows fibrous tissue overgrowth proximal to the patella. Impingement and occasional painful snapping occur upon extension of the knee.5 Subsequent design changes to the femoral component have minimized this problem. This painful and frequent cause of reoperation is still associated with cam and post posterior stabilized components.

Post breakage and wear is another complication that occurs uniquely to posterior stabilized implants. The tibial post, which functions to keep femoral contact points posterior on the tibia, is impacted repetitively by the femoral cam through normal use. Loads of 8 to 10 times body weight have been recorded with chair rise. The small surface area of contact between cam and post yields a significant concentration of stress. The post can break; this has been documented in case reports for both conventional polyethylene and highly cross-linked polyethylene.2,22 The tibial post serves as an additional source of wear contributing to osteolysis.21

Complications

Complications of posterior stabilized implants occur on the femoral side as well. The cam of the femur that articulates with the post requires more bone to be removed from the intercondylar notch than other designs. This results in bone loss that may complicate revision surgery. Case reports of fracture between the condyles as a result of intercondylar bone loss are a matter of concern.14

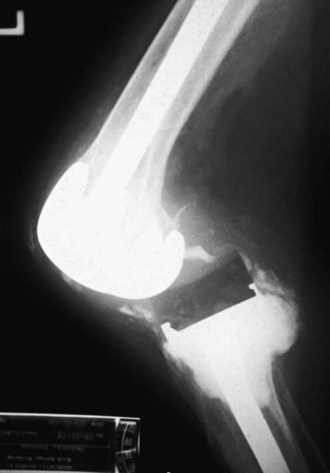

The femoral cam of posterior stabilized implants can be dislocated and can become lodged anteriorly (Fig. 110-2). The tibial post engages the femoral cam at approximately 60 to 75 degrees of flexion. No contact or posterior stabilization occurs during this early range of motion (ROM). Soft tissue imbalance may yield laxity that allows dislocation to occur.15 If this occurs, closed reduction and/or revision may be required.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree