Posterior Cervical Foraminotomy

Jacob M. Buchowski

Ronald A. Lehman Jr.

K. Daniel Riew

DEFINITION

Cervical radiculopathy is a clinical diagnosis defined by the presence of motor or sensory changes or complaints in a specific dermatomal distribution.

ANATOMY

Cervical radiculopathy is largely due to mechanical compression of the exiting cervical nerve roots.

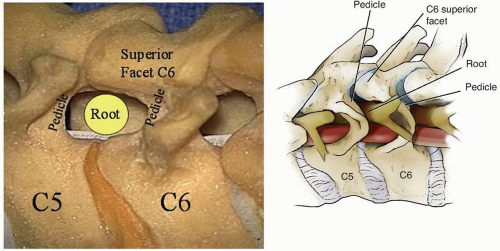

The intervertebral foramen is bounded by the following structures (FIG 1):

The disc and uncovertebral joint ventrally

The borders of the pedicles cranially and caudally

The superior articular facet of the caudal segment (eg, the superior articular facet of C6 at the C5-C6 foramen) dorsally

In the subaxial cervical spine, the foramen averages 9 to 12 mm in height and 4 to 6 mm in width, and in a young person, the cervical nerve root occupies approximately onethird of the available space in the foramen.

With increasing age, degenerative changes (osteophyte formation), disc protrusion, or cervical instability, this proportion may increase and signs of radiculopathy may develop.

PATHOGENESIS

Any process that causes impingement of the exiting cervical nerve roots can lead to cervical radiculopathy.

Potential etiologies of cervical radiculopathy include cervical spondylosis leading to foraminal stenosis due to uncinate or facet hypertrophy, disc herniation, instability, and anterolisthesis or retrolisthesis.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of cervical radiculopathy is not well studied, but about half of the adult population will have neck and radicular symptoms at some point during their lifetime.

In patients treated nonoperatively, up to 66% will have persistent symptoms and up to 23% of patients with persistent neck or radicular pain will be unable to return to their original occupation.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

When a patient presents with radiculopathy, a complete history and physical examination is of paramount importance.

Questions about the duration of the symptoms, location and nature of the pain, distribution of altered sensation and numbness (axial or radicular), presence of weakness, and any associated manifestations must be asked to understand the underlying pathology and target the offending level of cervical pathology.

Because radiculopathy can be associated with myelopathy, the presence or absence of balance difficulties, loss of bowel or bladder control, presence of constitutional symptoms, trauma, signs of dysdiadochokinesia, or change in neurologic status must be elucidated.

The physical examination should include motor and sensory evaluation (both gross and pinprick), reflex testing, upper and lower motor neuron signs, and cerebellar functional testing.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs of the cervical spine, including anteroposterior (AP), lateral, odontoid, oblique, and lateral flexion/extension

views, are used initially to evaluate for the presence of cervical pathology.

If symptoms have been present for at least 6 weeks, additional imaging is indicated and usually includes cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

If MRI is contraindicated, a cervical computed tomography (CT) myelogram may be beneficial.

A CT scan with coronal and sagittal reconstructions may be helpful in operative planning.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Cervical radiculopathy

Myelopathy

Myeloradiculopathy

Entrapment syndromes (eg, pronator syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, cubital tunnel syndrome)

Thoracic outlet syndrome

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Although cervical radiculopathy is common, only a few patients require surgical intervention, and despite a heightened clinical acumen for the diagnosis and treatment of cervical spondylosis, the mainstay of treatment remains nonsurgical.

Nonsurgical modalities that are initiated first include physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and activity modification.

If these methods fail, a selective nerve root injection at a designated level can be attempted with a high degree of safety and efficacy.

The purpose of the nerve root injection is twofold: to provide pain relief by decreasing inflammation through the use of a corticosteroid and to serve as a diagnostic tool to localize the offending pathology.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Posterior cervical foraminotomy is indicated for foraminal stenosis or a foraminal disc herniation resulting in a neurologic deficit such as a sensory deficit, motor weakness, and/or progressive symptoms that fail to respond to an appropriate course of nonsurgical treatment.

As with any surgical intervention, a thorough discussion with the patient and family about the desired outcomes and risks and benefits of the procedure must be undertaken before surgery.

Preoperative Planning

To perform an adequate foraminotomy, one must first understand the anatomy of the foramen.

The basic principle of the procedure is to unroof the foramen, which then allows the nerve root to displace dorsally away from the compressive pathology, which is anterior in most cases.

Less commonly, a portion of the superior facet may itself be a source of compression, which can then be directly removed by the posterior foraminotomy.

Because the superior articular facet of the caudal cervical segment forms the roof of the foramen, resection of the medial portion of the superior articular facet is necessary to adequately decompress the neuroforamen.

Similarly, because the pedicles form the cranial and caudal borders of the neuroforamen, adequate decompression requires resection of the superior articular facet to the lateral margin of the pedicles, as any overhang of the superior articular facet over the caudal pedicle can lead to persistent compression.

In contrast, because resection of more than 50% of the facet joint can lead to facet instability, resection of the superior facet lateral to the pedicle is unnecessary.

Positioning

Proper patient positioning is critical when performing posterior cervical foraminotomy to reduce blood loss and improve visualization of the operative field.

Although there are a variety of ways to position a patient, we routinely place the patient in bivector Gardner-Wells tongs traction and position the patient prone on an open Jackson frame (Mizuho Osi, Orthopaedic Systems, Inc., Union City, CA).

This table is quite versatile and allows for intraoperative alterations in patient positioning throughout the operation.

Typically, the table is tilted into reverse Trendelenburg to distribute blood into the abdomen and legs, thereby creating a more physiologic state for the patient and providing better visualization in the operative field.

To facilitate this position, the head of the table is placed on the top rung, and the foot of the bed is placed on the bottom rung.

The chest and abdomen are supported on bolsters that allow the abdomen to hang free, and the legs are supported in a sling with pillow support.

The shoulders are taped down on both sides to provide traction, thereby allowing better radiographic visualization of the lower cervical spine during intraoperative imaging.

Bivector traction is used with the aid of two separate ropes so that the neck is maintained in proper alignment, depending on the procedure being performed (FIG 2).

One of the ropes is placed in line and horizontal to the table through a pulley system, and the other is placed over a crossbar on the Jackson frame to facilitate placement of the head into extension.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree