Cervical Disc Replacement

Michael A. Finn

Arianne Boylan

Paul A. Anderson

ANATOMY

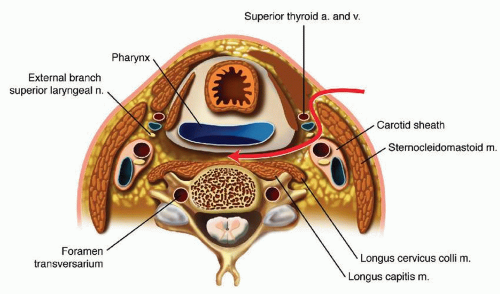

Familiarity with the anterior cervical anatomy is a necessity, particularly in regard to muscular, fascial, vascular, aerodigestive, nervous, and bony structures (FIG 1).

Approach level can be estimated by overlying anatomy:

C3: hyoid bone

C4-C5: thyroid cartilage

C6: cricoid cartilage, carotid tubercle

Muscular anatomy

The only muscle transected in the approach is the platysma, which lies superficially, just under the subcutaneous fat layer.

The sternocleidomastoid extends from the mastoid inferomedially to the sternomanubrial articulation and provides a lateral border for the exposure.

The omohyoid traverses the approach to the anterior cervical spine at approximately the C6 level and may be retracted or resected.

The longus colli muscles lie on the anterolateral surface of the cervical spine and are more widely spaced in the caudal direction than the cephalad. The position of the longus muscles is helpful in identifying the midline of the vertebral bodies.

Fascial planes

Superficial cervical fascia—lies just deep to the dermis and surrounds the platysma

Deep cervical fascia

Superficial layer: Also called the investing layer, this forms a collar around the neck and contains the sternocleidomastoid, among other structures, and blends with the lateral aspect of the carotid sheath.

Middle layer: Muscular part surrounds the strap muscles and great vessels, whereas the visceral part (also known as pretracheal fascia) encloses the anteromedial structures of the neck (aerodigestive tract and thyroid gland). It blends laterally with the carotid sheath.

Deep layer: The prevertebral part closely surrounds the vertebral column and prevertebral muscles. The alar part lies between the prevertebral and pretracheal fascia and defines the posterior border of the retropharyngeal space.

Vascular structures

The anterior and external jugular veins take variable courses superficial to the sternocleidomastoid and deep to the platysma.

The carotid artery and internal jugular vein are contained in the carotid sheath and help define the lateral margin of the deep exposure.

The vertebral arteries enter the transverse foramen at the C6 level in most (˜90%) of cases. The vertebral artery lies around 1.5 mm laterally to the uncovertebral joints in the middle cervical spine, although this is somewhat variable. The course of the vertebral artery takes is more medial, closer to the uncinate processes more rostrally.43

Neural structures

The recurrent laryngeal nerve ascends from the thoracic cavity in the tracheoesophageal groove to innervate all the intrinsic muscles of larynx with the exception of the cricothyroid.

The right recurrent laryngeal nerve arises in anterior to the subclavian artery and takes a more anterior course in the neck than does the left nerve, which arises more distally near the arch of the aorta.

Superiorly, the superficial laryngeal nerve crosses lateral to medial at the level of the hyoid to pierce the thyrohyoid membrane, at the level of the C3-C4 interspace, and provides innervation to the cricothyroid muscle as well as sensory innervation to the posterior pharynx.38,52

The spinal radicular nerve exits the spinal canal through the neural foramen at approximately 45-degree angle to the cord in the axial plane.

Bony and ligamentous structures

The anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) overlies the anterior aspect of the vertebral column and closely adheres to the intervertebral disc and endplate.

The disc underlies the ALL and is composed of a tough outer annulus fibrosus surrounding a soft gelatinous core, the nucleus pulposus.

The annular fibers are attached to the subchondral bone of the adjacent vertebral bodies.

The posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) runs down the posterior aspect of the vertebral column and is more robust centrally.

The uncovertebral joints, or uncinate joints, are situated laterally in the intervertebral space and serve as a landmark for anterior cervical decompressions.

Foraminal stenosis is often caused by hypertrophic degeneration of the uncinate joints.

PATHOGENESIS

Arthritic degeneration can affect any mobile joint in the spine.

Facet joint: neck pain (not treated with arthroplasty)

Uncovertebral joints: foraminal stenosis causing radiculopathy

Disc space

Osteophytic degeneration can cause central stenosis and myelopathy or radiculopathy.

Herniated disc fragments can be associated with significant inflammatory response and profound acute symptoms of radiculopathy or myelopathy.41

Genetic predisposition

Age

Tobacco use

Activity/occupation (heavy manual labor)

Obesity (body mass index [BMI] >30)

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of cervical radiculopathy is most often benign, with about 70% of patients having spontaneous improvement.24,31,48

Symptoms can recur or take on a waxing and waning course.

Between 6% and 35% matriculate to surgical intervention.

The natural history of myelopathy is controversial and appears to most often have a course of episodic or steady decline while improving with conservative treatment in only a minority of patients.32

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Radiculopathy

Patients often present with dermatomal pain, sensory changes (numbness, paresthesias), and weakness (Table 1).

May have dull ache in neck, shoulder, and scapula49

Often worse with extension; lateral rotation and bending toward symptomatic side; or when straining, sneezing, or coughing

Neurologic examination may be normal or reveal segmental weakness and reflex deficit.

Myelopathy

Over 50% of patients may present without significant painful complaints.13

Often presents as insidious decline of upper and lower extremity motor function:

Clumsiness of hands

Gait instability

Sensory dysfunction

Physical examination can reveal the following:

Weakness, often greatest in hands

Muscle wasting, often greatest in hands

Spasticity

Hyperreflexia with pathologic reflexes (Hoffman sign, Babinski sign)

Table 1 Cervical Radicular Function | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain x-rays may demonstrate arthritic changes such as disc space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, osteophyte formation, and foraminal stenosis (with oblique views) as well as overall alignment of neck and evidence of instability.

Computed tomography (CT) clearly delineates bony changes and may demonstrate bony foraminal compression. CT may be useful in evaluating for suspected ossification of the PLL when considering arthroplasty. CT myelography is useful in evaluating for the presence of neural compression in patients who are unable to undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and in those who have been previously instrumented.33

MRI is the imaging modality of choice for the evaluation of cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy and is sensitive in detecting disc herniations, osteophytes, spinal cord signal abnormalities, and central and foraminal stenosis.

Other modalities, including electrodiagnostic studies (electromyography [EMG]) and injections, may be used to clarify a diagnosis in difficult cases.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Cervical radiculopathy

Cervical myelopathy

Tumor (cranial or spinal)

Stroke

Motor neuron disease

Multiple sclerosis

Syringomyelia

Brachial plexopathy

Parsonage-Turner syndrome

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Radiation plexopathy

Peripheral nerve entrapment

Musculoskeletal

Shoulder disease (eg, rotator cuff)

Myofascial pain syndrome

Infection

Tumor

Tendinitis

Inflammatory arthropathy

Cardiac ischemia

Chest pathology

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative treatment should be attempted in most patients with radiculopathy.

Physical therapy or placement of a cervical collar have both been shown to be efficacious in acute (<1 month duration) symptoms and nonefficacious in cases of long-standing (>3 months) radiculopathy.31,42,45

Medications

Anti-inflammatory medications

“Nerve medications”—gabapentin, amitriptyline, Lyrica

Narcotics—limited role

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical intervention is indicated in cases of radiculopathy remittent to conservative care and in cases of progressive weakness.

Surgical intervention is indicated for cervical myelopathy in the presence of a compressive spinal cord lesion.

Indications

Treatment of symptomatic degenerative disease of the cervical spine, including disc degeneration, herniation, and osteophyte formation causing radiculopathy or myelopathy.

Symptoms resistant to conservative care for over 6 weeks or progressive neurologic deficit.

Treatment of degeneration or disc disease in cervical levels C2-C3 and C6-C7.

The Mobi-C cervical disc was U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved in 2013 for two-level cervical arthroplasty.

Cervical disc replacement remains controversial for the treatment of adjacent level disease.

Contraindications

Significant sagittal plane deformity (angulation >20 degrees)

Instability (>3.5 mm of motion in flexion/extension or spondylolisthesis)

Severe disc space collapse with limited range of motion (<2 degrees of motion)

Significant facet arthrosis

Ossification of the PLL

Treatment of fractures, infections, and tumors

Osteoporosis

Preoperative Planning

Films should be thoroughly examined for anomalous anatomy, such as an aberrant vertebral artery course, and for other possible causes of the patient’s symptoms. The depth and height of the disc space can be measured to estimate the size of the potential implant. Preoperative measurements should always be confirmed intraoperatively as endplate preparation will alter dimensions.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine with a small bump under the shoulders and the head in a doughnut in slight extension. A radiolucent table is used to allow for anteroposterior (AP) and lateral fluoroscopy.

The shoulders may need to be retracted inferiorly with tape to allow visualization of more caudal levels in large patients. Overly aggressive retraction should be avoided to reduce risk of brachial plexus injury.

Approach

A standard Smith-Robinson approach is used to access the anterior cervical spine.

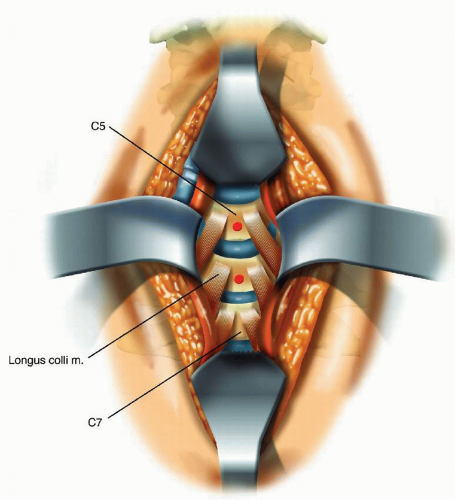

On initial exposure, the level of interest is confirmed radiographically, and the midline of immediately adjacent cephalad and caudad levels are marked with Bovie electrocautery prior to elevation of the longus muscles (FIG 2). Using a marking pen over the cauterized bone can help to more clearly delineate and preserve midline markings.

After the midline is clearly marked, the medial border of the longus colli muscle is incised with the Bovie electrocautery, and a longus flap is elevated. The longus should be elevated over approximately one-half the height of the adjacent vertebral body with care taken to preserve the annular attachments of the adjacent level. A self-retaining retractor is placed underneath the flap.

FIG 2 • Illustration showing exposure of the anterior cervical spine. The longus colli are used to identify the midline, which is then marked with Bovie electrocautery and a marking pen. |

TECHNIQUES

▪ Discectomy

The disc space is incised with a no. 15 blade scalpel, and a partial discectomy is performed with pituitary rongeurs.

A 3-0 curette is then used to separate the attachment of the annular fibers to vertebral endplate at the lateral margins of the disc space.

The separation with the curette proceeds from lateral to medial and superficial to deep, allowing for the lateral aspect of the disc to be removed en bloc.

This technique allows for rapid identification and exposure of the uncovertebral joints and thus the lateral margins of the exposure.

The disc is removed posteriorly to the PLL.

Use of Distraction: Pins, Tongs, Spreaders

Distraction posts may be placed before or after the discectomy, although placing posts after the discectomy allows better definition of the vertebral endplates and an improved understanding of their trajectory.

Although we place distraction posts in a mildly divergent trajectory when performing fusion, to reestablish cervical lordosis, we place them parallel in arthroplasty so as not to introduce hyperlordosis and for better fitment of the implant. The ProDisc system comes with unique distraction posts which should be placed parallel to the adjacent endplate as outlined in the following text.

The superior post should be placed high in the vertebral body so as not to interfere with endplate preparation, as the anteroinferior margin of the superior vertebral body often has an overhang which must be milled flush with the rest of the endplate to accommodate the implant.

Distraction about the endplate should be employed only to aid in visualization for neural decompression. Overdistraction during implant sizing and placement may lead the placement of an oversized implant which will have suboptimal mobility.

Endplate Preparation

The cartilaginous endplates are removed with care taken to preserve the integrity of the bony endplate as this will provide the structure to prevent subsidence. The cartilaginous endplates can often be removed with curettes. Alternatively, the high-speed drill can be used.

The inferior endplate of the superior level is most often concave, with an inferiorly protruding lip at the anteroinferior aspect. A high-speed drill is used to mill this flush with the posterior aspect of the endplate to create a broad, flat surface for implant apposition.

The superior endplate of the inferior level requires less preparation to create a flat surface. It is often slightly concave in the coronal plane, and the high-speed drill is used to mill down the proud lateral aspects and create a flat surface to accommodate the implant.

The final endplate preparation should be performed without distraction across the disc space to ensure flush and parallel endplates in the neutral position. A rasp can be used after burring to remove any small irregularities.

▪ Foraminotomy and Osteophytectomy

An aggressive foraminotomy is needed with arthroplasty as motion will be preserved and incomplete decompression will result in recurrent symptoms. Furthermore, foraminal expansion by means of distraction is not used in arthroplasty as an oversized implant will result in reduced motion due to increased ligamentous tension.

The PLL is left intact for the initial foraminotomy to protect the underlying neural elements.

The high-speed burr is used to perform the majority of the foraminotomy. We use the burr with a horizontal back and forth motion to remove posteriorly protruding osteophytes off the uncinate process. The burr can also be used in circular motion at the foraminal opening to enlarge the foramen. The burr should be operated under continuous motion and with frequent irrigation to prevent thermal injury to the underlying nerve root.

Final osteophytectomy can be accomplished with a small upgoing curette used in a rotational motion. The cutting edge of the curette can be angled in to bone for safe removal with minimal intrusion into the foraminal space.

A small (2 mm) Kerrison rongeur can also be used to expand the foraminotomy. Care should be taken to angle the butt of the instrument directly against the thecal sac to minimize chances of injuring the underlying exiting nerve.

Small instruments should be used when enlarging to foraminal opening to avoid traumatic damage to the exiting nerve.

Adequate foraminal decompression is confirmed by placing a nerve hook out the neural foramen without resistance.

The high-speed burr can also be used to remove posteriorly protruding osteophytes. The burr should be angled to attack the junction of the osteophyte and normal vertebral body, to reduce the chances of drilling out the endplate and more efficiently disconnect and remove the osteophyte. Final osteophytectomy can be accomplished with an upward angle curette used in a twisting motion.

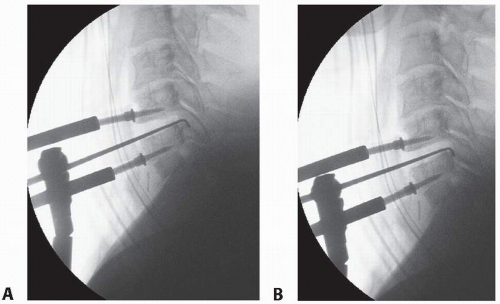

Resection of posterior osteophytes can be confirmed by placing a nerve hook or upgoing curette posterior to the vertebral bodies and taking a fluoroscopic image. The instrument should lie flush with the posterior aspect of the vertebral body (TECH FIG 1).

Anterior osteophytes should also be removed, either with rongeurs or a high-speed burr, to ensure flush fitment of devices with anterior flanges (eg, Prestige ST).

▪ Posterior Longitudinal Ligament Resection

The question of whether to resect the PLL in all cases of cervical arthroplasty is controversial.

PLL resection results in increased segmental motion without instability, which may aid the goal of arthroplasty.36,50

PLL resection may further aid in the adequate posterior positioning of the implant, especially in cases of significant arthritic degeneration, and may aid in restoration of a physiologic instantaneous axis of rotation.

PLL resection should be performed in all cases of posterior disc extrusion in which a fragment may be situated dorsal to the ligament.

The first step in resecting the PLL is the creation (or identification) of a rent in the ligament, allowing access to the epidural space. A rent may be present in cases of posteriorly herniated fragments, whereas one can otherwise be created with an upgoing curette.

The curette can be used in a rotational cephalocaudal fashion to slip between the fibers of the PLL and enter the epidural space.

Once the rent in identified or created, it can be expanded with an upgoing curette.

A small (2 mm) Kerrison can then be used to resect the ligament. Using the Kerrison at the intersection of the ligament and vertebral body ensures efficient resection.

Care must be taken to minimize dorsal pressure on herniated fragment behind the PLL with the butt end of the Kerrison rongeurs.

Care is also taken when resecting the ligament laterally to avoid grasping the exiting nerve root with the Kerrison rongeur.

▪ Prestige ST

The footprint size of the Prestige ST implant (TECH FIG 2) can be estimated preoperatively by measuring endplate depth and width on the preoperative MRI or CT.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree