Posterior Ankle Arthroscopy and Tendoscopy

C. Niek Van Dijk MD, PhD

Heleen Sonneveld MD

Peter A. J. De Leeuw MSc

Rover Krips MD, PhD

History of the Technique

Over the past 20 years arthroscopy of the ankle joint has become an important diagnostic and therapeutic procedure for chronic and posttraumatic complaints of the ankle joint. Burman,1 in 1931, regarded the ankle joint as unsuitable for arthroscopy because of its anatomy. Tagaki,2 in 1939, described systematic arthroscopic assessment of the ankle joint.2 Watanabe3 published a series of 28 ankle arthroscopies in 1972 followed by Chen4 in 1976. In the 1980s several publications followed.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 Some authors recommend routine placement of posterior portals in ankle arthroscopy.7,8 In these cases, a posterolateral portal is recommended. Because of the potential for serious complications, most authors feel the posteromedial portal is contraindicated in all but the most extreme situations.7,8,12,13 Arthroscopy of the subtalar joint was first described by Parisien and Vangsness11 in 1985. Endoscopic access to the posterior tibial tendons, including treatment of pathology, was first described by van Dijk et al.14 in 1997, followed by tendoscopy of the peroneal tendons15 in 1998 and endoscopic release of the flexor hallucis longus tendon in 2000.16

Hindfoot endoscopy has been demonstrated to give excellent access to the posterior ankle compartment, the subtalar joint, as well as extra-articular structures such as the os trigonum, the deep portion of the deltoid ligament, the posterior syndesmotic ligaments, and the tendons of the tarsal tunnel.16

Nagai17 was the first author to use the arthroscope to access the retrocalcaneal recess. He reported a case in which he identified the Achilles tendon and an avulsed portion of its insertion at the calcaneus. A description of the entry portals and the surgical approach to the retrocalcaneal bursa appeared in 1997.18 The results of a first cohort of 22 consecutive patients, with a minimal follow-up of 2 years, was published in 2000.16

Indications and Contraindications

Indications can be divided according to the location of the pathology.

Articular Pathology

Posterior Compartment Ankle Joint

The main indications are the débridement and drilling of posteriorly located osteochondral defects of the ankle joint, removal of loose bodies from the posterior compartment, removal of ossicles, posttraumatic calcifications, avulsion fragments, resection of posterior tibial rim osteophytes, treatment of chondromatosis, and treatment of chronic synovitis.

Posterior Compartment Subtalar Joint

The main indications are osteophyte removal and débridement of degenerative changes in the subtalar joint, removal of loose bodies, treatment of an intraosseous talar ganglion by drilling, curetting and bone grafting, and subtalar arthrodesis (Fig. 66-1A,B,C,D).

Periarticular Pathology

Posterior Ankle Impingement

Posterior ankle impingement is a pain syndrome. The patient experiences posterior ankle pain that is mainly present on

forced plantarflexion. Posterior ankle impingement can be caused by overuse or trauma. Distinction between these two seems important since posterior impingement through overuse has a better prognosis.19 A posterior ankle impingement syndrome through overuse is mainly found in ballet dancers and runners.20,21,22 Running that involves forced plantarflexion such as downhill running can put repetitive stress on the posterior aspect of the ankle joint.23 In ballet dancers the forceful plantar flexion during the en pointe position or the demi-pointe position produces compression at the posterior aspect of the ankle joint. The joint mobility and range of motion (ROM) gradually increase through exercise. In the presence of a prominent posterior talar process or an os trigonum, this can lead to compression of these structures (Fig. 66-2A,B).

forced plantarflexion. Posterior ankle impingement can be caused by overuse or trauma. Distinction between these two seems important since posterior impingement through overuse has a better prognosis.19 A posterior ankle impingement syndrome through overuse is mainly found in ballet dancers and runners.20,21,22 Running that involves forced plantarflexion such as downhill running can put repetitive stress on the posterior aspect of the ankle joint.23 In ballet dancers the forceful plantar flexion during the en pointe position or the demi-pointe position produces compression at the posterior aspect of the ankle joint. The joint mobility and range of motion (ROM) gradually increase through exercise. In the presence of a prominent posterior talar process or an os trigonum, this can lead to compression of these structures (Fig. 66-2A,B).

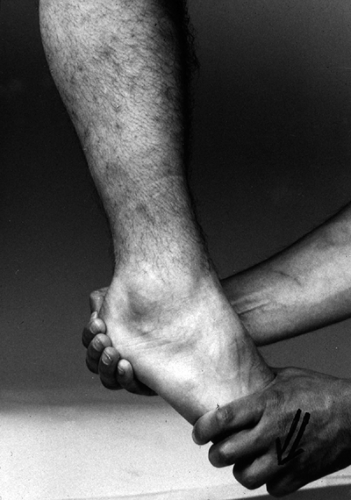

The presence of an os trigonum itself does not seem to be relevant.20 This anatomic anomaly must be combined with a traumatic event such as a supination trauma, a hyperplantarflexion trauma, dancing on hard surfaces, or pushing beyond anatomic limits. The forced hyperplantarflexion test is most important for the diagnosis (Fig. 66-3). A negative test rules out a posterior impingement syndrome. A positive test is followed by a diagnostic infiltration of local anesthetic. If the pain on forced hyperplantarflexion disappears, the diagnosis is confirmed.

Deep Portion of the Deltoid Ligament

Eversion or hyperdorsiflexion trauma can result in avulsion fragments, posttraumatic calcification, or ossicles in the deep portion of the deltoid ligament. Patients experience posteromedial ankle pain especially on running and walking on uneven ground.

Flexor Hallucis Longus

A flexor hallucis longus tendonitis is often present in patients with a posterior ankle impingement syndrome. The pain is located posteromedial. In ballet dancers, it is present in plié and especially grand plié. The flexor hallucis longus tendon can be palpated behind the medial malleolus. By

asking the patient to repetitively flex the big toe with the ankle in 10 to 20 degrees of plantarflexion, the flexor hallucis longus tendon can be palpated in its gliding channel behind the medial malleolus. The tendon glides up and down under the palpating finger of the examiner. In case of stenosing tendonitis or chronic inflammation, crepitus and recognizable pain can be provoked. Sometimes a nodule in the tendon can be felt to move up and down under the palpating finger.

asking the patient to repetitively flex the big toe with the ankle in 10 to 20 degrees of plantarflexion, the flexor hallucis longus tendon can be palpated in its gliding channel behind the medial malleolus. The tendon glides up and down under the palpating finger of the examiner. In case of stenosing tendonitis or chronic inflammation, crepitus and recognizable pain can be provoked. Sometimes a nodule in the tendon can be felt to move up and down under the palpating finger.

Peroneal Tendons

Tenosynovitis of the peroneal tendons, dislocation, rupture, and snapping of one of the peroneal tendons account for the majority of symptoms at the posterolateral side of the ankle joint.24,25 A differentiation must be made with (fatigue) fractures of the fibula, lesions of the lateral ligament complex, and posterolateral impingement (os trigonum syndrome).

Peroneal tendon disorders are often associated and secondary to chronic lateral ankle instability. As the peroneal muscles act as lateral ankle stabilizers, more strain is placed on these tendons in chronic lateral instability, resulting in hypertrophic tendinopathy, tenosynovitis, and ultimately in (partial) tendon tears.26,27,28 Postsurgery and postfracture adhesions and irregularities in the posterior aspect of the fibula (sliding channel) can be responsible for symptoms in this region.15

Posterior Tibial Tendon

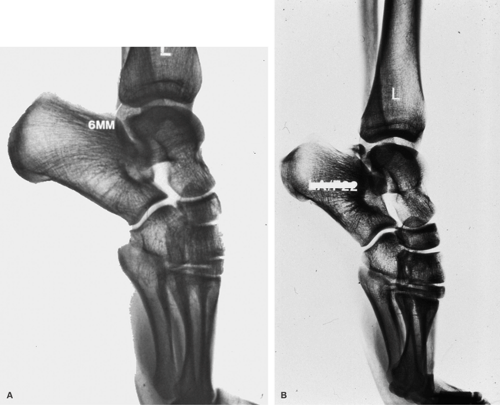

The posterior tibial tendon plays an important roll in normal hindfoot function.29 Several investigators have described development of posterior tibial dysfunction as the disease progresses from peritendinitis to elongation, degeneration, and rupture27,28,29,30,31 (Fig. 66-4A,B). Tenosynovitis is often seen in

association with flat feet and psoriatic and rheumatic arthritis. In the early stage of posterior tibial dysfunction, tenosynovitis is the main symptom. Tenosynovectomy can be performed if conservative treatment fails.32 Postsurgery and postfracture adhesions and irregularity of the posterior aspect of the tibia (sliding channel) can be responsible for symptoms in this region.

association with flat feet and psoriatic and rheumatic arthritis. In the early stage of posterior tibial dysfunction, tenosynovitis is the main symptom. Tenosynovectomy can be performed if conservative treatment fails.32 Postsurgery and postfracture adhesions and irregularity of the posterior aspect of the tibia (sliding channel) can be responsible for symptoms in this region.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree