Posterior Ankle Arthroscopy and Hindfoot Endoscopy

C. Niek van Dijk

Tahir Ögüt

DEFINITION

Because of their nature and deep location, posterior ankle problems pose a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.

Arthroscopic evaluation of posterior ankle problems by means of routine ankle arthroscopy using an anteromedial, anterolateral, and posterolateral portal is difficult because of the shape of the ankle joint. In cases in which the ankle ligaments are lax, it is possible to visualize and treat the pathology of the ankle joint itself, but pericapsular or extracapsular posterior pathologic conditions are not accessible through conventional arthroscopic portals.

A two-portal posterior endoscopic approach with the patient in the prone position affords excellent access to the posterior ankle, the subtalar joint, and the pericapsular and extra-articular structures.22

ANATOMY

Posterior ankle arthroscopy and hindfoot endoscopy enable visualization and accessibility to the posterior half of the tibiotalar joint, the subtalar joint, and extra-articular structures such as the os trigonum, the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon, and the posterior syndesmotic ligaments.

The posterior intermalleolar ligament, also called the tibial slip or marsupial meniscus, is a structure with consistent location but varying size and width. It is distinct from the posteroinferior tibiofibular ligament and separated from it by a small gap filled with synovial tissue.2

The os trigonum is a secondary center of ossification of the talus. It is present in 1.7% to 7% of normal feet.4 When this ossification center remains separate from the posterolateral process of the talus (the trigonal process or the Stieda process), it is referred to as the os trigonum. The prevalence of unilateral and bilateral (ununited) os trigona is 10% and 1.402%, respectively.4,17

The FHL tendon originates in the posterior leg then runs within a tendon sheath that begins 1 cm proximal to the subtalar joint and binds the tendon to the posterior talus and calcaneus, forming the fibro-osseous tunnel, which may restrict FHL motion.6,10

The posteromedial neurovascular bundle (tibial nerve and posterior tibial artery) are consistently medial to the FHL tendon throughout its course. Instruments introduced from the posteromedial portal do not risk injuring the neurovascular bundle provided they remain lateral to the FHL.7 Sitler et al15 dissected 13 cadavers and found that the tibial nerve was located posterior to the FHL tendon in two specimens.

A posteromedial portal located 1 cm proximal to the level of the tip of the lateral malleolus is on average 2.9 mm further removed from the medial neurovascular bundle than a portal placed 1 cm more proximally.7

PATHOGENESIS

Posterior ankle pain may be a result of the following:

Posterior ankle impingement or os trigonum syndrome

FHL, posterior tibial, or peroneal tendinopathy

Posttraumatic calcifications or exostoses

Bony avulsions

Tibiotalar or subtalar loose bodies

Tibiotalar or subtalar osteochondral lesions or arthrosis

Any combination of these entities

Overuse injuries play an important role in the pathogenesis of posterior ankle pain.

Repetitive minor trauma in the ankle, as seen in athletes, can induce posterior ankle and/or hindfoot osteophyte formation.18

Typically, to produce symptoms, an os trigonum must be disturbed by some traumatic event, such as a supination or forced plantarflexion injuries, dancing on hard surfaces, or pushing beyond physiologic limits.18

The pain is thought to be a result of the following:

Symptomatic motion between the relatively unstable os trigonum and talus

Compression of thickened joint capsules (intermalleolar ligament)1

Impinging scar tissue between the os trigonum and tibia

Compression between os trigonum and calcaneus (referred to as dancer’s heel)

FHL tendinopathy is usually attributable to stenosing tenosynovitis rather than tendinosis or rupture3; it has only rarely been reported at sites other than the posteromedial ankle.3,10 However, immunohistochemical studies have suggested an avascular zone of the tendon in the segment of tendon that passes behind the talus.14

NATURAL HISTORY

Patients present with posterior ankle pain.

Posterior ankle impingement can be caused by overuse (chronic pain) or trauma (acute pain). It is important to differentiate between these two because posterior impingement from overuse has a better prognosis.18

In chronic conditions, stenosing tenosynovitis of the FHL tendon may coexist with os trigonum syndrome; this leads to poorer outcome if surgical treatment is delayed.4

Nonsurgical treatment for os trigonum syndrome is successful in approximately 60% of patients.8

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients experience deep pain in the posterior aspect of the ankle joint, mainly with forced plantarflexion.

On examination, there is pain on palpation of the posterior aspect of the talus.

During the passive forced plantarflexion test, the investigator can apply a rotational movement on the point of maximal plantarflexion, thereby “grinding” the posterior talar process or os trigonum between the tibia and the calcaneus.

A positive test result, in combination with pain on posterolateral palpation, should be followed by a diagnostic infiltration of an anesthetic (with or without corticosteroid).

Posteromedial pain on palpation does not necessarily indicate impingement.18

Tenderness on palpation over the musculotendinous junction of the FHL is diagnostic for FHL tendinitis; pain can be elicited by forced simultaneous ankle and first metatarsophalangeal joint dorsiflexion.3,10

“Pseudo hallux rigidus” may coexist with posteromedial ankle pain. Hallux dorsiflexion may be limited with ankle dorsiflexion but restored with ankle plantarflexion. This examination finding/phenomenon has been reported to be secondary to nodular thickening of the proximal FHL that impinges within the fibro-osseous tunnel on the posteromedial ankle.10

Palpation of posterior talar process is a sensitive test for posterior ankle impingement. A positive test should be followed by a hyperplantarflexion test.

The hyperplantarflexion test is positive when the patient experiences recognizable pain at the moment of impact. It is a highly sensitive test for posterior ankle impingement. A negative test rules out a posterior ankle impingement syndrome.

If the pain on forced plantarflexion disappears, the diagnosis is confirmed.

Posteromedial ankle palpation is sensitive for FHL tendinitis.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

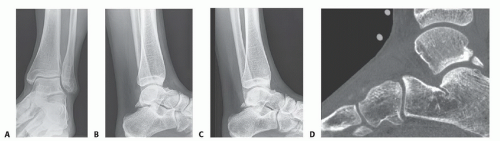

In patients with posterior ankle impingement, the anteroposterior (AP) ankle view typically fails to demonstrate abnormalities (FIG 1A).

On the lateral view, a prominent posterior talar process or os trigonum can sometimes be recognized.

As the posterolaterally located posterior talar process or os trigonum is often superimposed on the medial talar tubercle, detection of an os trigonum on a standard lateral view is often not possible (FIG 1B).

For the same reason, calcifications can sometimes not be detected by this standard lateral view.

We recommend lateral radiographs with the foot in 25 degrees of external rotation in relation to the standard lateral radiographs (FIG 1C).

Bone scintigraphy effectively localizes talar and peritalar injuries.5

Computed tomography defines the exact size and location of calcifications, bony fragments, osteochondral lesions, or intraosseous talar cysts (FIG 1D).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful for detection of bone contusions, edema, posterior capsular or ligament thickening,1 talar osteochondral lesions, and FHL tenosynovitis.

MRI has been reported to accurately identify FHL tendinitis in 82% of patients,10 represented by intermediate or low signal intensity on T2-weighted images.4

Fluid in the FHL tendon sheath is frequently seen in MRI without clinical signs of FHL tendinitis. Fluid in the tendon sheath of the FHL must be combined with changes in the tendon itself to be a sign of a tendinitis.

Bone edema in the os trigonum is an important diagnostic finding.

It is a sign of chronic compression of the os trigonum between distal tibia and calcaneus.

It can be a sign of degeneration of the cartilage of the undersurface of the os trigonum. In these cases, the bone edema is combined with bone edema of the calcaneus.

It can also be a sign of movement between the os trigonum and the talus. In these cases, there is bone edema in the posterior talus as well. These cases represent a pseudoarthrosis type of lesion.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree