8. Positional release techniques applied in sports massage

Positional release techniques (PRT) are a group of noninvasive effective manual techniques utilizing fine-tuned positions of optimal soft tissue relaxation and pain relief as a treatment for musculoskeletal dysfunctions. PRT techniques produce valuable physiological effects, stemming from both neurological and circulatory changes, when a dysfunctional area is placed in a position of optimal comfort and pain relief (Chaitow 1997). The creation of PRT techniques can be attributed to a number of practitioners, all of whom have contributed significantly to the advancement of manual soft tissue treatment.

The benefits of PRT for the sports massage therapist are many and its practical applications should not be overlooked. Due to the gentle nature of PRT, the techniques can be included in almost any athletic treatment situation. PRT applied in preevent massage can assist relaxation of overly tensed muscles; in postevent massage the techniques may reduce or prevent cramping tendencies; and PRT may assist quick recovery of muscles during interevent sports massage, especially when combined with massage and stretch techniques.

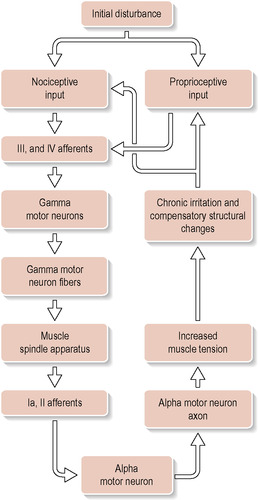

It is believed that during certain conditions, the flow of information between muscles and the central nervous system becomes dysfunctional. A trauma, rapid stretch of a previously approximated and relaxed muscle, or some other stressor may generate a disruption of the normal neural proprioception, causing overstimulation of the muscle spindles and nociceptors (Jones 1995), rendering them hypersensitive and triggering affected muscles into prolonged contraction (Fig. 8.1). Since the affected muscles in this condition commonly are positioned in an extremely shortened and relaxed position at first, the muscle spindles are quiet. As the affected muscles are stretched rapidly, the spindles commence intense signaling to the central nervous system, triggering a myotatic reflex response with subsequent muscle contractions. The rapid change of state in the muscles concurrently renders the muscle spindles hypersensitive, and the central nervous system continues to interpret the neural proprioceptive inflow as if the affected muscles are truly in a state of stretch, even after the muscles are returned to their normal resting length, which triggers continued contractions. The perpetuated state of contraction concurrently activates spontaneous relaxation of antagonistic muscles (Jones, 1995 and Chaitow, 1997), causing muscular imbalance that places stress on the affected joints and surrounding tissues, leading to persistent pain and dysfunction. If left untreated, the condition may remain for a long time, so that any attempt at increasing stretch or joint movement only generates additional tension and pain.

|

| Figure 8.1 |

The sports massage therapist may perceive this as if the treated muscles are incapable of relaxing. Instead of struggling with the tissue by merely attempting to increase the applied stretch force, whether generated from sports massage techniques or therapeutic muscle stretching, the opposite approach is more beneficial. By palpating either the distressed tissue or a “tender point” (see “Strain Counterstrain,” below), the dysfunctional part of the athlete’s body is gently moved into a position of optimal soft tissue relaxation and pain relief. Subsequently holding this “position of ease” for a predetermined period of time will commonly release the dysfunctional state of spasm and/or tension in the tissue by lessening proprioceptor activity.

The noninvasive nature of PRT makes it very useful even in more delicate situations. Since it is virtually impossible to injure or traumatize an athlete using PRT, it makes these techniques a very useful tool also for early sports injury rehabilitation treatment. The basic concept behind PRT may be perceived as ingeniously simple and straightforward, but the possible initial therapeutic challenge lies more in the ability to register the subtle tissue reactions the athlete’s body generates during the treatment. It often takes a bit of initial training and practice to be able to work efficiently with PRT, but the therapeutic rewards once adequate palpatory skill is acquired are substantial.

Fascial release (Chaitow 1997)

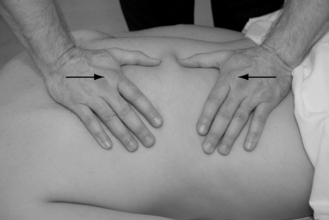

One effective soft tissue technique based on PRT principles is to simply approximate an area, large or small, of tensed soft tissue, and hold it for 3min, followed by a slow release toward normal length. This tends to lower the tone in the tissue, and is an excellent tool for tensed well-developed muscles in athletes. The soft tissue is either pushed together with the hands (Fig. 8.2), or a part of the athlete’s body is moved as a lever to relax the treated tissue. It is easier to utilize massage and stretch techniques after the elevated soft tissue tone is lowered.

|

| Figure 8.2 |

Functional technique

Functional technique is based on osteopathic manipulation techniques focusing on function rather than structure alone (Hoover 2001). Osteopathic practitioners at the New England Academy of Applied Osteopathy coined the term “functional technique”, during the 1950s (Bowles 1981) (see Box 8.1). This early PRT method, with roots tracing back to the origin of osteopathic medicine (Bowles, 1981 and Chaitow, 1997), utilizes movement of the dysfunctional tissue or segment, with simultaneous subjective palpation for the “position of ease” in the treated soft tissue. Functional technique establishes a state of “demand-response” where identified somatic dysfunctions are restored to normal functions (Pedowitz 2005). The method is based on reducing afferent information from mechanoreceptors and nociceptors in the affected tissues (Chaitow 1997).

Box 8.1

Motive hand – Something generating a motion demand through the treated tissues under the listening hand. It can be hands, fingers, thumbs, or even a verbal command to the athlete to generate motion.

Motion demand – a desired movement for assessment, i.e. flexion, extension, lateral flexion, abduction, adduction, rotation, circumduction, etc. generated by the motive hand.

Response – The response from the motion demand in the tissue or segment, reaching the listening hand for assessment.

Listening hand – Any tactile part of the therapist used to assess the response in the treated tissue or segment.

As the treated area is moved toward “ease,” normally involving a certain degree of approximation of the soft tissue, a noticeable palpable sensation of relaxation occurs as the muscle tone decreases (Chaitow 1997). This natural relaxation was termed “dynamic neutral,” and is defined as the state where soft tissues discover balance when the motion of the structure they assist is free and within normal physiological limits (Bowles 1981). Dynamic neutral should not be viewed as a static condition, but instead as a continuous normal state during daily activity (Chaitow 1997). It is the natural state to which all treated dysfunctional areas should be restored (Hoover 2001).

In the basic therapeutic execution of functional technique, one hand will serve as a motive hand (Chaitow, 1997 and Hoover, 2001), creating motion demands by moving a joint or tissue in all directions, whilst the other hand acts as the listening hand (Chaitow, 1997 and Hoover, 2001), registering any change (from the response) of tension in the palpated soft tissue. The listening hand must not move, and should register only compliance or noncompliance, i.e. “ease” or “bind,” in the tissue (Bowles, 1981 and Hoover, 2001). The motive hand (Chaitow, 1997 and Hoover, 2001) moves the tissue or body part in all potential directions, whilst the listening hand registers binding tendencies in the soft tissue (Chaitow 1997). If only a sensation of ease is noted from the movements, the tissue function is considered normal. If there is however a sensation of binding, in any direction, a dysfunctional pattern is present in the palpated area (Chaitow, 1997 and Hoover, 2001).

During treatment, the motion that produced the binding response is repeated, and the listening hand monitors the tissue as the movements are subsequently modified until the greatest feeling of ease is restored (Chaitow, 1997 and Hoover, 2001).

There are two main variations of functional technique:

• Balance and hold.

• Dynamic functional.

Balance and hold

The listening hand lightly palpates the treated soft tissue while conforming to its shape. Each motion demand generated by the motive hand is, one by one, assessed for its respective position of ease. The dysfunctional joint is moved through all possible directions, with each separate movement starting at the previously applied movement’s position of ease, making one position of ease “stack” on top of another (Chaitow 1997) until all combined positions of ease are accumulated, clearing the previous dysfunctional condition.

Example of balance and hold of the shoulder

1. The listening hand lightly touches the area of pain in the shoulder, simultaneously conforming to its shape (Fig. 8.3).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree