Ponseti Technique in the Treatment of Clubfoot

Kenneth J. Noonan

The Ponseti method of clubfoot correction consists of a series of foot manipulations and cast applications designed to correct the clubfoot deformity. Ninety percent of feet will require heel-cord tenotomy at the end of the casting sequence. Orthotic management helps prevent recurrence. In the author’s experience, 20% of feet may require additional surgical treatment as a toddler. This method obviates the need for extensive posterior medial and lateral release in greater than 97% of infants (1, 2).

This chapter outlines the pertinent pathoanatomy and method of clubfoot treatment as outlined by Professor Ignacio Ponseti (3). The goal of treatment for idiopathic clubfoot is to produce a flexible, plantar-grade foot that is painless for the life of the individual and that does not require orthotics after the completion of treatment.

The congenital clubfoot is a complicated, three-dimensional deformity with four components, as described by the acronym CAVE: (a) Cavus deformity refers to the increased height of the arch of the foot. (b) Adductus deformity refers to the medial deviation of the forefoot relative to the hind foot. (c) Varus deformity refers to the adducted and inverted positioning of the calcaneus under the talus. (d) Equinus deformity refers to the increased degree of plantar flexion of the foot (Fig. 23-1). The acronym CAVE also directs the order in which the four deformities are purposefully addressed via the Ponseti method. Cavus is corrected first, adductus and varus follow sequentially, and equinus is the last to be corrected via heel-cord tenotomy in 90% of feet.

At birth, the whole clubfoot appears to be severely inverted and supinated; the forefoot is adducted and pronated relative to the midfoot and hindfoot, the latter of which is in varus and equinus. Although the entire foot is supinated, the forefoot is pronated relative to the hindfoot, thus resulting in the cavus. Anatomically, adductus is due to medial displacement and inversion of a wedge-shaped navicular that articulates with the medial aspect of the head of the talus (which has a

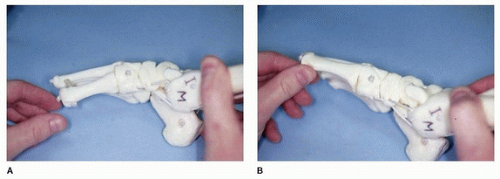

medially directed neck) and that is in close proximity to the medial aspect of the tibia. The cuboid is also adducted in front of the calcaneus and along with the metatarsals, thus further adducting the midfoot. Hindfoot varus is due to the adducted and inverted position of the calcaneus under the talus (Fig. 23-2). As such, the distal end of the calcaneus lies directly beneath the talar head and not in the lateral position as normally seen.

medially directed neck) and that is in close proximity to the medial aspect of the tibia. The cuboid is also adducted in front of the calcaneus and along with the metatarsals, thus further adducting the midfoot. Hindfoot varus is due to the adducted and inverted position of the calcaneus under the talus (Fig. 23-2). As such, the distal end of the calcaneus lies directly beneath the talar head and not in the lateral position as normally seen.

FIGURE 23-1 Bilateral clubfoot in a 4-week-old boy. This figure clearly demonstrates the cavus, adductus, and varus deformity. The hindfoot deformity is always stiffer than is the forefoot deformity. |

FIGURE 23-2 Hindfoot varus is a result of adduction (A) and eversion (B) of the calcaneus underneath the body of the talus. |

Equinus deformity is due to the position of the calcaneus under the talus as a result of shortened extrinsic tendons, such as the gastrocsoleus, tibialis posterior, and long toe flexors. The talus is plantarflexed in the ankle plafond, and the posterior ankle and subtalar capsules are also tight. Midfoot breach (dorsiflexion) resulting from hindfoot stiffness may lead to deceptive physical assessment of actual hindfoot deformity when the foot is dorsiflexed. In these cases, the foot may appear to dorsiflex up to 10 degrees; however, the true equinus deformity can be appreciated by palpating the heel fat pad, which feels empty due to proximal retraction of the calcaneal tuberosity. Radiographically, midfoot breach is confirmed by an increased tibial-calcaneal angle, and a plantarflexed talus results in a rocker bottom deformity.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

The Ponseti method is the preferred method for initial treatment in all clubfeet. Idiopathic feet can be fully corrected in 6 to 7 weeks. Nonidiopathic clubfeet take longer to be corrected with this method, and full correction can be expected in 50% of feet. In cases of incomplete correction, the

presenting deformity will be vastly improved and secondary surgery will be less extensive. Great care is needed in performing the Ponseti method in children who have teratologic clubfoot, as the stiffness of these insensate feet may lead to skin sores or pressure ulcers when aggressive correction is attempted with the cast (Fig. 23-3).

presenting deformity will be vastly improved and secondary surgery will be less extensive. Great care is needed in performing the Ponseti method in children who have teratologic clubfoot, as the stiffness of these insensate feet may lead to skin sores or pressure ulcers when aggressive correction is attempted with the cast (Fig. 23-3).

For decades, Dr. Ponseti taught that the results of his method were directly dependent upon the age at which the child began the treatment of manipulation and casting. Within the past 5 years, however, this philosophy has changed, as older children with neglected or incompletely treated clubfeet have been successfully treated with excellent results (2). Ideally, treatment should be started as soon as convenient for the family and within the general health and well-being of the infant. At our institution, we have determined that results of treatment initiated within the first month of life are the same as when treatment is initiated within the second month.

Special consideration is needed for those babies who are born premature. As a practical matter, it is difficult to perform the Ponseti method in an intensive care unit (ICU) due to the constraints of monitors and lines. In addition, the practitioner must anticipate what he or she plans to do with the corrected clubfoot in prenatal babies. The standard Ponseti method requires patients to be placed into an abduction orthosis with shoes attached to a bar. Unfortunately, there is no such device available for small premature babies who have full correction of their clubfoot deformity within 4 to 5 weeks of delivery. In general, it is often best to institute physiotherapy for preterm babies in the ICU. Therapists should be instructed on gentle manipulation and forefoot abduction as described by Dr. Ponseti. These exercises may be performed daily to maintain the suppleness of the foot prior to institution of casting once the child begins the treatment.

In patients with recurrent or undercorrected clubfoot, it is appropriate to begin the Ponseti method, no matter what age, and to continue treatment until no further correction can be obtained. Practitioners in developing countries report that the results from this method may yield partial correction in some toddlers and young children with idiopathic clubfeet who were untreated when infants (4).

Overview of Technique

In the Ponseti method, the foot is manipulated for 30 to 60 seconds in a defined manner that stretches ligaments and tendons of the malpositioned tarsal bones. A cast is then applied to hold the corrected position for at least 5 to 7 days. During the intervening days, the ligaments and tendons stretch. The tarsal bones readapt and remodel their articular surfaces (5). Successful treatment of the clubfoot via this method depends on several important principles: the three tarsal joints—subtalar, calcaneocuboid, and talonavicular joints—move simultaneously, and the deformity is corrected during the manipulation. Despite this fact, it is helpful for the beginner to keep the CAVE concept in mind, as it will guide him or her to understand that the first deformity corrected is the cavus and then the adductus, which then leads to correction of the varus deformity. In the standard clubfoot, it is critical that the foot be maintained in equinus until full correction of cavus, adductus, and varus deformities but before heel-cord tenotomy. Premature dorsiflexion of the foot will block calcaneal abduction and eversion, thus decreasing varus correction and increasing the potential for a rocker bottom deformity.

The practitioner should stretch the foot within comfort of the baby. By carefully observing the child, the method should be eased if the child stops feeding or begins crying or has facial grimacing. It is beneficial for formula or breast milk to be withheld for a couple of hours prior to the treatment so that the infant may be fed during cast application. This strategy helps to relax the infant, greatly

facilitating the casting. One should chose a dimly lit room without load noises; soothing background music can help relax the infant too.

facilitating the casting. One should chose a dimly lit room without load noises; soothing background music can help relax the infant too.

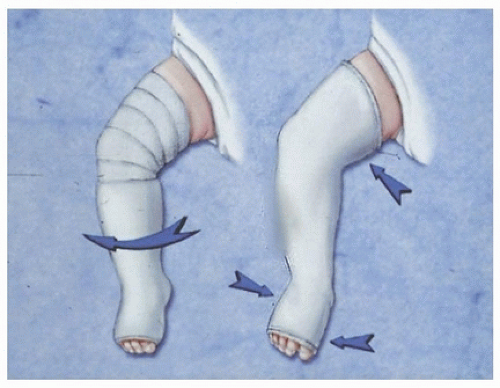

Long-leg, bent-knee plaster casts are always used to prevent the child from kicking off the cast. These casts also maintain the forefoot abduction moment, which is required for correction of the adductus and varus deformities. Although some practitioners use synthetic cast material, the author continues to follow the principles as described by Ponseti, who described plaster of Paris applied over thin layers of cotton padding.

Casts are usually applied over thin layers of cotton webbing. In cases of bilateral deformities, time is of the essence and often the child can become agitated after one full (toe to groin) cast application; it is advantageous to apply the cotton and to mold the plaster casts of the feet and lower legs first. The short-leg cast must be carefully applied with attention to detail and is much easier done when the child is relaxed; applying the upper portions of the cast can be safely done in the case of an agitated infant (Fig. 23-4). Prior to extending the short-leg cast into the long-leg portion, the popliteal fossa must be carefully inspected to ensure that no compression is present from the posterior proximal edge of the short-leg casts. Both casts are then finished by flexing the knee to 90 degrees and extending the upper thigh plaster over cotton roll. In large agitated infants, we will consider fiberglass to finish off the upper leg portion, as it is stronger and lighter. In general, manipulation and casting are performed on a weekly basis. An accelerated treatment protocol (5-day interval) may be considered in infants who live a great distance from the practitioner; however, more frequent

sessions are likely to be poorly tolerated and may lead to significant foot edema (6). The manipulations may be performed at 2-week intervals in children older than 6 months of age, but the ultimate time to correction may be longer.

sessions are likely to be poorly tolerated and may lead to significant foot edema (6). The manipulations may be performed at 2-week intervals in children older than 6 months of age, but the ultimate time to correction may be longer.

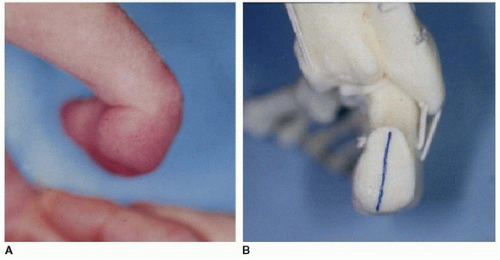

Technique

Cavus Correction The goal of the first casting session is to correct the cavus deformity. This will result in a more rigid forefoot lever arm, which is instrumental in reducing the metatarsus adductus through further forefoot abduction and casting. The pronated forefoot is supinated, and the first metatarsal is elevated. A well-molded plaster cast is then applied with a flat toe plate, thus maintaining all of the metatarsal heads in a row (Fig. 23-5). This maneuver corrects the cavus deformity, though it does result in a potentially alarming global increase in inversion of the foot; it is of no consequence. Experienced practitioners may combine cavus correction with the slight forefoot abduction during the initial cast session to simultaneously correct some of the adductus deformity. In general, it is a good idea to avoid aggressive forefoot abduction during the first cast session so that infants can become used to the method. It is not uncommon for a child to be uncomfortable for the first 24 to 36 hours after casting and manipulation. If an infant is persistently inconsolable following application of a plaster cast, the cast should be removed and the skin inspected for irritation. Because cast sores are more likely to occur when the cast slips distal on the child’s foot, parents need to be instructed to watch for proximal migration of the toes (Fig. 23-6). Hyperflexion of the knee to 120 degrees and immobilization with an anterior plaster splint may be needed in patients who have a history of complex clubfoot or who have difficulty with frequent cast slippage.

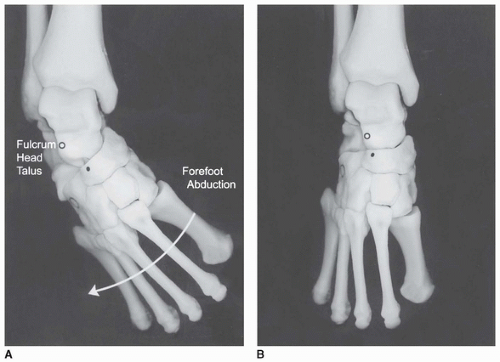

Metatarsus Adductus and Varus Correction Correction of adductus and varus deformities occur sequentially and are a result of the predominant manipulation in which the forefoot is abducted against counterpressure on the head of the talus (Fig. 23-7). The head of the talus is just distal to the fibula. The practitioner must be careful to place the counterpressure accurately—not on the fibula or the calcaneocuboid joint. Anatomically, this maneuver will

correct the metatarsus adductus by reduction of the metatarsals and the navicular on the head of the talus and the cuboid on the calcaneus. With subsequent casting, the calcaneus will begin to evert and abduct under the talus. The hindfoot will then convert from a varus to a neutral or valgus position. To promote efficient correction, it is critical that abduction be performed with the forefoot in supination, thus maintaining prior correction of forefoot cavus, and with the foot in equinus so that the calcaneus will not be prevented from everting and abducting underneath the talus. Dynamic forefoot abduction may be promoted by slightly externally rotating the previously molded and hardened short-leg portion of the cast while the upper thigh portion is applied and molded (Fig. 23-8).

correct the metatarsus adductus by reduction of the metatarsals and the navicular on the head of the talus and the cuboid on the calcaneus. With subsequent casting, the calcaneus will begin to evert and abduct under the talus. The hindfoot will then convert from a varus to a neutral or valgus position. To promote efficient correction, it is critical that abduction be performed with the forefoot in supination, thus maintaining prior correction of forefoot cavus, and with the foot in equinus so that the calcaneus will not be prevented from everting and abducting underneath the talus. Dynamic forefoot abduction may be promoted by slightly externally rotating the previously molded and hardened short-leg portion of the cast while the upper thigh portion is applied and molded (Fig. 23-8).

FIGURE 23-6 Families are instructed to look for retraction of the toes within the cast (shown here), which can predispose the foot to a pressure sore on the heel. |

At subsequent visits, the cast is removed with either a cast knife or a cast saw. If the latter is used, the technician must be aware that these casts are applied over thin layers of padding, thus exposing

the infant to the risk of saw burns by the inattentive technician (Fig. 23-9). After cast removal, the child undergoes manipulation of the forefoot against pressure over the talus. This time may be increased in children with stiffer feet. Weekly manipulations and castings are performed with the forefoot in slight supination and with the foot in equinus until full correction of forefoot adduction and hindfoot varus is obtained (Fig. 23-10). In general, the full correction of these two deformities can be expected when the thigh-foot axis is approximately 60 degrees externally rotated. Once this angle has been obtained, the final deformity that needs to be corrected is the equinus deformity.

the infant to the risk of saw burns by the inattentive technician (Fig. 23-9). After cast removal, the child undergoes manipulation of the forefoot against pressure over the talus. This time may be increased in children with stiffer feet. Weekly manipulations and castings are performed with the forefoot in slight supination and with the foot in equinus until full correction of forefoot adduction and hindfoot varus is obtained (Fig. 23-10). In general, the full correction of these two deformities can be expected when the thigh-foot axis is approximately 60 degrees externally rotated. Once this angle has been obtained, the final deformity that needs to be corrected is the equinus deformity.

FIGURE 23-8 Slight external rotation (curved arrow) is performed when converting the short-leg portion to the long-leg cast. This leads to dynamic forefoot abduction (short arrows) while in the cast. |

FIGURE 23-9 Cast saw burns may result from cast removal by neophyte cast technicians who are not aware of the thin cotton and the intimate mold that are utilized with the Ponseti method. |

Equinus Correction The success of the Ponseti method depends on adequate correction of the Achilles contracture. Yet for the neophyte, it can be challenging to decide whether the foot being treated is deserving of a heel-cord release; this is because the apparent ability to dorsiflex the ankle

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree