Chapter 13 Podiatry, biomechanics and the rheumatology foot

KEY POINTS

An understanding of foot and ankle biomechanics can help in assessing foot function and identifying treatment options

An understanding of foot and ankle biomechanics can help in assessing foot function and identifying treatment optionsFOOT INVOLVEMENT IN THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

INFLAMMATORY JOINT DISEASE

Rheumatoid arthritis

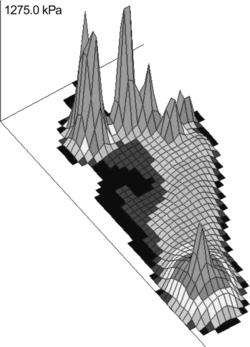

Small joint inflammation in the hands and feet is the hallmark of early rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint synovitis can be detected using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 97% of patients (Boutry et al 2003). The MTP joints are involved early: MRI can detect bone oedema and synovitis even when the finger joints are normal (Ostendorf et al 2004). Erosive changes also occur early in these joints, and their grade of destruction is high (Belt et al 1998). Cardinal signs and symptoms are pain and stiffness which is worse in the early morning and after periods of standing and walking. Pain under the MTP joints is likened to ‘walking on pebbles, glass or stones’. The feet can throb and burn and stiffness is a persistent background feature. The forefoot can rapidly widen with ‘daylight sign’ between the toes related to MTP synovitis, and joint capsule and periarticular ligament damage (Fig. 13.1). Patients report that normal footwear becomes tight, uncomfortable and difficult to wear. On examination the metatarsal squeeze test (gripping the MTP joints and compressing them together) may be positive and one or more MTP joints swollen and tender on palpation.

Early involvement in the peritalar region affects the tenosynovium of tibialis posterior in around 60% of patients (using MRI) and the midtarsal, subtalar and ankle joints in around 25% of patients (Bourty et al 2003, Fleming et al 1976). Pain and stiffness are common and subtle but clinically important changes in function can be detected within 2 years from onset (Turner et al 2006). Mild-to-moderate pes planovalgus (flat footedness) can be found. However, this tends to be passively correctable. In contrast to the MTP joints, ankle and subtalar joint erosions and destruction occur infrequently and in the later stages (> 15 years). True bony ankylosis is rare (Belt et al 2001).

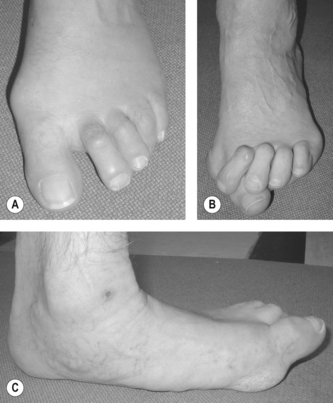

In established RA the prevalence of foot symptoms is over 90% (Michelson et al 1994). Synovial pannus and joint erosions weaken intra-articular and peri-articular structures, whilst joint effusion distorts the capsule. Therefore under normal weightbearing loads progressive and severe deformities can develop. In the forefoot, fibular drift of the toes mimics ulnar deviation of the finger joints and if severe the subluxed or dislocated toes can over- or under-ride adjacent toes. Hallux valgus, tailors bunion and hammer, claw or mallet toe deformity can rapidly develop (Briggs 2003). Bursitis between or under the metatarsal heads is common and can be detected using MRI in around 60% of cases (Boutry et al 2003). Morton’s interdigital neuroma may also be more prevalent in RA patients (Awerbuch et al 1982). Painful callosities can develop over the dorsum of prominent toe joints, medially on a hallux valgus joint or around the plantar metatarsal heads (Korda & Balint 2004).

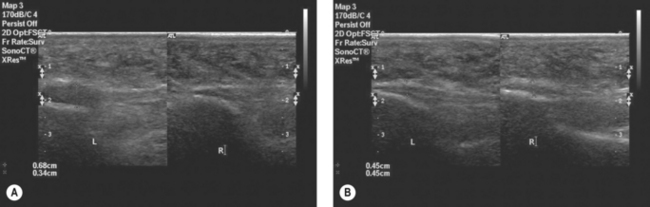

Persistent disease in the peritalar region leads to the development of pes planovalgus and in severe cases the medial longitudinal arch may be completely collapsed (Turner et al 2008a). Pes planovalgus is associated with tendinopathy of tibialis posterior (Bouysset et al 2003, Jernberg et al 1999). Clinically the tendon may be swollen and inflamed medially at the ankle region (Woodburn et al 2002). MRI or ultrasound (US) imaging reveals tendon enlargement, tenosynovitis, tendinopathy, and intra-substance splits, however true rupture occurs in less than 5% of cases (Lehtinen et al 1996, Premkumar et al 2002). Pain and swelling in the posterior heel region may be associated with retrocalcaneal bursitis, Achilles enthesopathy and posterior calcaneal erosions (Falsetti et al 2003). Enthesopathy of the plantar fascia, or more rarely a plantar nodule, may lead to plantar heel pain.

Extra-articular manifestations such as peripheral arterial disease (nail fold infarcts, cutaneous vasculitis and digital gangrene), neuropathy, ulceration and subcutaneous nodules affect some patients with RA. Foot ulceration and infection are major clinical red flags, especially in patients treated with biologic therapies, glucocorticosteroids and some disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Ulceration occurs most commonly over the dorsal aspect of hammer toes, over the metatarsal heads and the medial bunion with hallux valgus deformity. The overall prevalence of ulceration in people with RA is 9.7% (Firth et al 2008a) and common risk factors include deformity, elevated skin contact pressures, loss of protective sensation, peripheral vascular disease, active disease and steroid use (Firth et al 2008b). The risk of serious infection involving the skin is recognised in RA patients receiving anti-TNF therapy, and a number of case series have described infection associated with skin ulceration (Otter et al 2005) and spontaneous onychocryptosis (in-growing toenail) (Davys et al 2006a).

Seronegative spondlyoarthropathies

The seronegative spondyloarthropathies (SpAs) share a number of common clinical features, of which asymmetric oligoarthritis, peripheral small joint arthritis, enthesopathy, and dactylitis affect the feet. Peripheral enthesitis (characterised by inflammation at sites of tendon, ligament and joint capsule into bone) is regarded to be a hallmark feature of SpAs and may be associated with enthesophyte formation (bony proliferation). Inflammation may occur at any entheses, however, enthesitis at the heel is reported to be the most frequent and occurs at the attachment of the Achilles tendon (AT) and plantar fascia to the calcaneus (Olivieri et al 1992). In routine clinical practice enthesitis is diagnosed based on patient symptoms and clinical examination to determine tenderness on palpation. However, clinical examination underestimates the presence of enthesitis and detection is improved when imaging techniques such as MRI and high resolution US are used (Balint et al 2002, D’Agostino et al 2003, Galluzzo et al 2000).

Management of SpAs relies on DMARD and biologic drug therapy targeting the underlying disease mechanisms. However, ultrasonographic data suggest that despite intensive pharmacological management enthesitis in the foot is detectable in a high proportion of patients (approximately 60-80% of patients) and is poorly correlated with systemic parameters of disease activity (Borman et al 2006, D’Agostino et al 2003, Genc et al 2005). Biomechanical factors, including foot function, may contribute to the development of enthesopathies (Benjamin & McGonagle 2001) and may help explain the discordance between disease activity parameters and enthesitis. It has been suggested poor alignment of the rearfoot and control of foot pronation, may make the enthesis at the heel more vulnerable to injury however, data are currently lacking to support this theory.

Forefoot deformity and nail pathologies are especially common in patients with PsA. A recent survey found 95% of patients had some deformity in the forefoot (Hyslop et al 2008). PsA will often present initially in the interphalangeal (IP) joints of the toes and then the MTP joints. Usually both IP joints in the toe are affected providing the characteristic clinical presentation dactylitis or ‘sausage toe’. Inflammation at the IP and MTP joints can cause stretching and damage to the joint capsules and collateral ligaments leading to the typical toe joint deformities of RA. Inflammation can also lead to the formation of joint erosions, however, unlike in RA these tend to occur in the juxtaarticular region (adjacent to the articular surface). The course and progression of radiological damage can vary in patients with PsA, and a number of common features in the foot have been identified (Fig 13.2). These include the characteristic pencil in cup deformity (Gold et al 1988), the so called ivory shaft (increased bone density in the shaft of the phalanx), resorption of the distal phalanx, resulting in a characteristic pointed toe pulp (Moll 1987).

JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS

Foot problems such as synovitis, limited range of motion, malalignment and deformity have been reported in over 90% of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), generally increasing in severity with age, disease duration and in those with polyarticular disease (Spraul & Koenning 1994). Foot pain, deformity and impaired function are persistent problems even in those children optimally managed on DMARD and biologic therapy (Hendry et al 2008). Synovitis in the ankle and rearfoot joint occurs in approximately one-third of patients across all disease subtypes and is associated with limited ankle range of motion, pronated rearfoot and midfoot joints, and weakness of the ankle dorsiflexors/plantarflexors (Brostrom et al 2002, Spraul & Koenning 1994). Pes planovalgus is twice as common as varus heel alignment (pes cavus foot type) in these children (Mavidrou et al 1991).

Synovitis, effusion, erosive changes and deformity at affected MTP joints are observed in about one-fifth of JIA children and hallux valgus is common (Ferrari 1998). Deformities such as splaying of the forefoot; hammer, claw, and mallet toe deformity and MTP joint subluxation can rapidly develop. Leg length discrepancy, deformity and proximal joint malalignment resulting from growth disturbances can also impact on foot structure and function. Other problems such as Achilles tendinopathy, retrocalcaneal bursitis, tenosynovitis and plantar fasciitis occur in association with specific disease sub-types.

Disabling foot pain in JIA is associated with abnormalities in gait, either as a direct consequence of joint damage or as compensation to underlying impairments (Brostrom et al 2002, Hendry et al 2008, Witemeyer et al 1981). Typically these include reduced walking speed, increased double-limb support time, and step asymmetry. Gait can also be cautious and guarded with reduced heel-strike and push-off force (Brostrom et al 2002).

OSTEOARTHRITIS

The commonest sites for osteoarthritis in the foot are the 1st MTP joint (hallux rigidus), the ankle joint and the tarsometatarsal joints. Hallux rigidus is found in approximately 5% of adults above the age of 50 (Shereff & Baumhauer 1998) and is associated with trauma, metabolic and congenital disorders. The condition is often bilateral and affects more women than men. Patients may complain that the joint is stiff and painful and made worse by walking. Examination reveals a dorsal exostosis which is palpable and tender along the MTP joint line. Dorsiflexion motion is limited and painful. Radiographs reveal loss of joint space, dorsal osteophytes, subchondral bone sclerosis and cysts.

Primary osteoarthritis of the ankle joint occurs in less than 10% of all cases and over 70% are post-traumatic (Saltzman et al 2005, Valderrabano et al 2008). The lower rate of primary disease in comparison to the hip and knee is attributed to anatomic, biomechanical, and cartilage properties which protect the joint from degenerative changes (Huch et al 1997). Trauma is usually associated with malleolar fractures and ankle ligament lesions. The ankle is stiff and painful with mild-moderate effusion. Pain can be elicited on specific movements such as dorsiflexion/inversion and crepitus can be felt. Range of motion will be limited, the joint unstable and gait adapted to achieve relief. Bony enlargement, malalignment and/or deformity, can progressively develop (Fig. 13.3). Malalignment is distributed in favour of varus across all etiologies (55% varus, 37% neutral, 8% valgus) (Valderrabano et al 2008). Joint space narrowing, osteophtye formation, subchondral bone sclerosis, and cyst formation are typical radiographic features as well as varus malalignment, anterior protrusion of the talus and flattening of the tibial plafond (articular surface of the distal end of the tibia).

CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASES

Foot involvement is prevalent but often overlooked in the two most common connective tissue diseases; scleroderma and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The feet are involved less frequently and later than the hands in scleroderma but nevertheless 90% prevalence has been reported (La Montagna et al 2002). Radiological changes in the joints in these patients include juxtaarticular demineralisation, distal phalange resorption, joint space narrowing, and extraarticular calcification. Radiological foot abnormalities have been reported in 26% of patients (Allali et al 2007). Approximately 90% of patients suffer from Raynaud’s syndrome which can lead to pain in the feet and digital ulceration, scarring and in some cases gangrene and amputation (La Montagna et al 2002, Sari-Kouzel et al 2001).

Localised thickening and tightening of the skin of the toes (sclerodactyly) and flexion contractures have been reported in 6% of cases (La Montagna et al 2002) and are associated with atrophy of the underlying soft tissues. Subcutaneous calcinosis occurs infrequently (6%) but can be extremely painful and disabling if it occurs on a weight bearing area of the foot. Whilst problems in the feet occur less frequently than those in the hand they can be a major source of morbidity and disability in patients with scleroderma.

Non-erosive arthritic manifestations (Jaccoud’s type arthropathy) involving the foot and ankle have been reported in patients with SLE. Common foot deformities found in these patients are hallux valgus, subluxation and fibular deviation of the MTP joints, and widening of the forefoot (Mizutani & Quismorio 1984, Reilly et al 1990). Erosive changes are rare in this group; however, hook like erosions caused by pressure erosion beneath the distorted joint capsules in the deformed joints may appear and have been reported at the metatarsal heads. Accelerated atheroma is a well recognised complication of SLE and abnormal ankle brachial pressure indices have been reported in almost 40% of patients (Theodoridou et al 2003). However, it rarely leads to critical peripheral ischaemia and gangrene is a relatively uncommon finding (Jeffrey et al 2008). Raynaud’s syndrome occurs in approximately 30% of cases (Bhatt et al 2007).

CRYSTAL JOINT DISEASE

Sudden onset of pain, swelling, erythema and limited movement in the foot or ankle is characteristic of acute gout. The 1st MTP joint is most commonly involved, although acute gouty arthritis can involve the dorsum of the foot or ankle. Diagnosis of gout is established when monosodium urate (MSU) crystals are found in joint aspirate. Tophi are chalky white deposits of MSU that are large enough to be seen on radiographs and may occur at virtually any site but commonly occur in the joints of the hand and foot (Harris et al 1999). The rate of tophi formation correlates with duration and severity of hyperuricaemia (Gutman 1973). Intra-articular tophi are associated with the formation of bone erosions. However in contrast to RA, these are ill defined with overhanging edges and are not associated with osteopenia (Dalbeth et al 2007). Compared with RA, joint space narrowing occurs late in the disease or joint space widening may also occur in advanced disease (Dalbeth et al 2007). Moreover there is a strong relationship between bone erosion and the presence of intraosseous tophus. This suggests that tophus infiltration into bone as the dominant mechanism for development of bone erosion and joint damage in gout (Dalbeth et al 2008).

HYPERMOBILITY

Hypermobility (excessive mobility) can occur at a single joint or can be widespread throughout the body. There are several conditions associated with hypermobility, including Ehlers-Danlos disease, Marfan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta and benign joint hypermobility syndrome (BJHMS) which is the most common and will be the focus of this section. BJHMS has been defined as generalised joint laxity and hyperextensibility of the skin in the absence of any systemic disease. The pattern and course of musculoskeletal problems can vary considerably in patients with BJHMS from intermittent problems in a single joint to persistent widespread involvement of joints and soft tissues. A high proportion of patients with BJHMS have intermittent joint and soft tissue pain, joint effusions, dislocations, and they also have a tendency to bruise and scar easily.

Patients with BJHMS have poorer proprioceptive feedback and muscle strength, although this can be improved with proprioceptive exercises (Hall et al 1995, Sahin et al 2008a, Sahin et al 2008b). The proprioceptive system plays a critical role in maintenance of joint stability, including body position and movement of joints. Therefore deficits in proprioceptive function can make joints and soft tissues more vulnerable to minor traumas and may allow acceleration of degenerative joint conditions (Hall et al 1995). Hypermobility at the ankle and foot has been reported in a high proportion of patients. In the foot it is common for patients with BJHMS to report ankle instability and recurrent ankle inversion sprains (Finsterbush et al 1982). Other common features include joint instability, pes planovalgus deformity, subluxation of the MTP joints and hallux valgus (Fig. 13.4). In a review of a 100 consecutive patients, the most frequent complaint (48% of cases) was pain in the feet and calf associated with pes planovalgus deformity. Both general and local hypermobility at the 1st MTP joint have been linked with hallux valgus deformity (Carl et al 1988, Myerson & Badekas 2000).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree