Chapter 23 Pilates

Initial Examination

Initial Examination

Employment: Personal injury attorney

Recreational Activities: Walking, hiking

Medications: Percocet, Neurontin

Function: Pain: low back pain, at rest=4/10; sit-ting and standing 10 minutes=7/10; walking 10 minutes=7/10

INVESTIGATING THE LITERATURE

Preliminary Reading

Joseph H. Pilates (1880-1967)

Many books have been written about Pilates and are useful resources for learning about its history as an approach to fitness and health.1–10 Joseph Hubertus Pilates was born in Germany in 1880. As a child, he suffered from asthma and many other illnesses, which resulted in fragility and weakness.1,2 Determined to overcome his ailments, Pilates became passionate about physical exercise and fitness. He studied many forms of exercise including yoga and martial arts during his young adulthood and began to develop his own philosophy and method of training and fitness. While interned in a prison camp for German nationals during World War I, Pilates taught his exercises to inmates and began developing equipment that could be used to rehabilitate clients who were restricted to their hospital beds.1,2,4,8 In 1923 Pilates left Germany and emigrated to the United States. On the crossing, he fell in love with a woman named Clara, who became his wife. Together, they opened an exercise studio in New York City. Within a few years, Pilates’ unique method of physical and mental conditioning caught the attention of professional dancers and choreographers who sought to maintain or regain strength and flexibility as they recovered from a variety of performance-related injuries. Dance artists such as ballet master George Balanchine and modern dance notable Martha Graham supported Pilates’ method of body conditioning and exercise and studied with him for many years.1,4,9

Pilates’ original program consisted of a series of mat exercises designed to build abdominal strength and develop control of the body. Then he designed and built several pieces of equipment to enhance the exercises and substitute for the manual assistance he was providing for his clients. Pilates also trained the first generation of teachers in his New York studio, including Romana Kryzanowska, Kathy Grant, Ron Fletcher, and several others. Although many of the original teachers have branched out to different areas of the country and have incorporated their own experiences and style into the Pilates method of exercise, the original principles of Pilates have been maintained and continue to be passed down through several generations of Pilates instructors.1

Contrology

Perhaps the best way to learn about Pilates’ philosophy of fitness and approach to exercise is to read a book written by Pilates entitled Return to Life Through Contrology, which originally was published in 1945. In this text, Pilates explains that, “Physical fitness is the first requisite of happiness …(and that) physical fitness is the attainment and maintenance of a uniformly developed body with a sound mind fully capable of naturally, easily, and satisfactorily performing our many and varied daily tasks with spontaneous zest and pleasure” (p. 6).10 Contrology, the term Pilates used to describe his method of exercise, was designed to develop coordination of the mind, body, and spirit through purposeful and repetitive exercises. These exercises, according to Pilates,10 would strengthen muscles and correct abnormal postures while encouraging flexibility and graceful movement. By mindfully attending to the breath and the body’s posture and movement of each repetition of every exercise, the exercises of Contrology were proposed to “correct wrong postures, restore physical vitality, invigorate the mind and elevate the spirit” (p. 9).10 Central to the Pilates method of body conditioning and exercise is the “powerhouse,” located between the bottom of the rib cage and the hips. Here muscles, including the rectus abdominis, transversus abdominis (TA), obliques, multifidus, erector spinae, gluteals, and quadratus lumborum, support the spine and trunk. When strong, the powerhouse improves alignment and posture and provides a base from which all movements can be generated.1 Most of the more than 500 exercises described by Pilates focus on strengthening the powerhouse or what some exercise and rehabilitation professionals now call the core, while training the mind and the body to work together. Proponents of Pilates suggest that the Pilates method of body conditioning and exercise can improve strength, endurance, balance, and coordination3 and address respiratory problems and chronic pain.2 Other claims include improved sexual enjoyment, better sleep, and the elimination of “love handles.”1,9

Principles

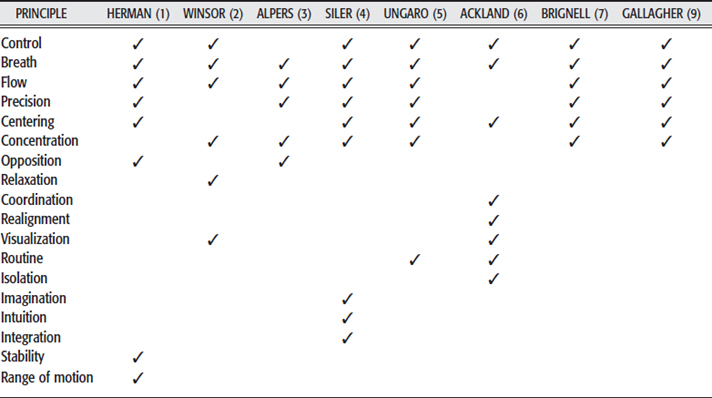

Most contemporary teachers of the Pilates method of exercise and conditioning ascribe to the principles or concepts outlined by Pilates in his writings. Although the terminology used to name these principles may vary from instructor to instructor (Table 23-1), their explanations of the underlying concepts as originally described by Pilates are consistent. The terms most commonly used to identify Pilates’ principles and concepts are provided below.

Control

Pilates’ method of exercise requires control of every movement. Strength is developed by moving slowing against and with gravity, avoiding momentum as a means to complete a movement. Each exercise is executed with breath, concentration, and control.

Breath

Every exercise described in Pilates’ text10 includes instructions for a specific breathing pattern of when to inhale and when to exhale. According to Pilates, correct breathing requires a full inhalation and complete exhalation so that the blood can receive “vitally necessary life-giving oxygen” and the muscles can be stimulated into greater activity (p. 13).10

Concentration

Some Pilates instructors and authors have identified coordination, opposition, isolation, stabilization, visualization, and relaxation as additional principles of the Pilates method of exercise. Explanations of these principles seem to overlap with the principles of control, breath, flow, precision, centering, and concentration. The concepts of precision and control, for example, include the expectation that the exercises are performed in a coordinated manner, in which some muscles are active in performing a movement, while other muscles, such as the abdominals, contract to maintain stability of the torso. The exercises also require the ability to isolate certain muscles to contract and shorten, while opposing muscles are relaxed and lengthened so that movement can flow with ease and precision.

Probably the most accessible form of Pilates is a group of floor exercises often referred to as the mat program. This collection of exercises is the focus of most books written about Pilates1–10 and for which clear descriptions and illustrations or photographs are available. Exercisers are encouraged to perform an abdominal scoop and achieve and maintain a neutral spine while performing the exercises. Adherence to these positions helps ensure the building of strength and length of the powerhouse musculature and helps guard against injury.10 A sample of three mat exercises can be seen in Figures 23-1 to 23-3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Evaluation

Evaluation Plan of Care

Plan of Care Reevaluation

Reevaluation