Abstract

Objective

Our objective was to study the effects of physical training combined with dietary measures in obese adults. In a second step, we sought to compare two training protocols and establish the additional contribution of strength training.

Methods

We performed a randomized, prospective survey from July 2004 to November 2007. Included patients were randomized into three groups: a control group (G1), a group (G2) performing dietary measures and a programme of treadmill training at 60% of each individual’s maximum heart rate (HR max ) and a group (G3) who followed the G2 programme supplemented with strength training. All patients underwent an initial and final assessment of anthropometric & cardiovascular parameters, muscle strength, dyspnoea during activities of daily living, metabolic disorders, psychological status and quality of life.

Results

The greatest weight loss (7.24%) was observed in G3. Reduction in waistline measurement (WL) of 4.3% and 10.26% were noted in G2 and G3, respectively ( p < 0.001). The percentage fat body mass fell by 10.4% in G3 ( p < 0.001) and 8.6% in G2 ( p = 0.03). We particularly noted an improvement in physical condition in groups 2 and 3, with lower HR and blood pressure values at rest and at maximum effort. The overall improvement in both arm and leg muscle strength was greater for G3 than for G2. Likewise, we noted an improvement in the metabolic parameters and depression & anxiety scores for the trained groups (G2, G3), relative to the control group (G1). We also noted improvements in the total impact of weight on quality of life (IWQOL) lite score of 15.2% in G2 and 18% in G3.

Conclusion

Our survey demonstrated the beneficial effect of combining dietary measures and physical training in obese patients. In addition to weight loss, the programme enabled a reduction in the patients’ body fat mass and abdominal obesity, a correction of metabolic disorders and an improvement in aerobic capacity. The improvement in all these parameters also enhanced the patients’ psychological status and quality of life. The addition of strength training produced notable improvements in weight loss, arm muscle strength and abdominal obesity.

Résumé

Objectif

Notre objectif était d’étudier l’apport du réentraînement à l’effort associé à la prise en charge diététique chez une population d’obèses en comparant deux types de protocoles incluant ou pas des exercices de renforcement musculaire segmentaire.

Méthodes

Il s’agit d’une étude prospective randomisée, allant de juillet 2004 à novembre 2007. Tous les patients obèses ont été randomisés en trois groupes : un premier groupe (G1) témoin, un deuxième groupe (G2) comportant les patients qui ont suivi en plus des conseils hygiénodiététiques, un programme de réentraînement à l’effort avec des exercices de type aérobie sur tapis roulant à 60 % de la fréquence cardiaque maximale et un troisième groupe (G3) comportant les patients qui ont suivi en plus du protocole du G2 des exercices de renforcement musculaire segmentaire des quatre membres et de la paroi abdominale. Les paramètres évalués étaient les paramètres anthropométriques, le retentissement cardiovasculaire, la force musculaire, la dyspnée, les troubles métaboliques, l’état psychologique et la qualité de vie.

Résultats

La perte de poids la plus importante a été constatée dans le G3 avec un pourcentage d’amélioration moyen de 7,24 %. Une diminution du tour de taille (TT) a été notée dans les deux groupes réadaptés G2 et G3 avec des taux respectifs de 4,3 et de 10,26 % ( p < 0,001). Le pourcentage d’amélioration des chiffres de masse grasse était de l’ordre de 10,4 % dans le G3 ( p < 0,001); de l’ordre 8,6 % dans le G2 ( p = 0,03). Nous avons constaté une amélioration de la condition physique surtout dans les groupes réadaptés à travers une diminution des chiffres de la fréquence cardiaque et de la tension artérielle aussi bien au repos qu’à l’effort maximal. L’amélioration de la force musculaire était globalement plus importante pour G3 que pour G2 aussi bien aux membres supérieurs et inférieurs. De même on a constaté une amélioration significative des chiffres du bilan biologique ainsi que du score de dépression et de l’anxiété et du score total de qualité de vie dans les groupes réadaptés.

Conclusion

Notre étude a pu confirmer l’effet bénéfique de l’association de la diététique au réentraînement à l’effort dans la prise en charge de l’obèse. L’association des exercices de renforcement musculaire a permis une amélioration plus notable de certains paramètres à savoir la perte pondérale, la force musculaire essentiellement des membres supérieurs et de l’obésité abdominale.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Obesity is a frequent pathology with a multitude of complications; over the last few decades, it has become an increasingly significant public health concern in both developed and developing countries .

Obesity must be considered as a disease in its own right but is also a risk factor for other diseases, as a result of overweight and the frequently associated metabolic disorders. In fact, life-threatening cardiovascular diseases, handicapping joint diseases and behavioural disorders can all result from obesity. When combined with psychological deterioration, this cohort of comorbidities strongly decreases quality of life and requires multidisciplinary disease management as soon as possible in the course of the disease . The medical treatment of obesity is based on a combination of physical activity, dietary measures and psychological support. The management of obesity with a variety of short- and long-term measures has been examined in several meta-analyses . This management is necessary since it can produce (in addition to weight reduction ) an improvement in associated parameters, such as cardiovascular risk factors , metabolic disorders , and the functional & psychological status (guaranteeing better quality of life) . The first aim of our work was to determine the impact of a combination of physical training and dietary measures on metabolic, cardiovascular, psychological and quality-of-life parameters in a population of obese adults, compared with a control group. The second aim of our work was to compare two types of physical training protocols for obese individuals.

1.2

Patients and methods

1.2.1

Patients

This was a randomized prospective study carried out from July 2004 to November 2007. We included obese patients with a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 30 kg/m 2 who had been referred by the Hedi Chaker Sfax University Hospital Endocrinology Department to the Physical Medicine & Functional Rehabilitation Department’s Training Unit. All patients were treated on an outpatient basis.

We excluded patients who presented a contra-indication to effort, a major orthopaedic problem making gait on a treadmill impossible (such as invalidating knee osteoarthritis), severe psychiatric disorders, a personal history of heart disease and/or a recent myocardial infarction, patients not consenting to the protocol and those who had not diligently followed eight consecutive weeks of training.

A food survey was performed for all patients, with subsequent prescription of an appropriate diet.

In all, we recruited 152 detrained obese patients. Only 83 patients were included in the study analysis because the remaining 69 had not correctly completed the initial training programme (due to a lack of diligence, a health problem of some sort or the excessive distance between their place of residence and the Training Unit) and had thus been excluded from the study.

Included patients were randomized into three groups. With initial population sizes of 50, 51 and 51 for groups 1, 2 and 3. 21, 25 and 23 patients were excluded, respectively. In terms of the patients who were evaluated at the start and at the end of the programme, the groups were as follows:

- •

29 patients in G1 (controls), who had not received dietary and health advice and had not performed the physical exercise programme;

- •

26 patients in G2, who received dietary and health advice and also underwent aerobic, treadmill-based training;

- •

28 patients in G3, who received dietary and health advice and underwent an aerobic, treadmill-based training programme supplemented with arm and leg muscle strength exercises.

1.3

Methods

1.3.1

Evaluated parameters

All patients were evaluated during two special consultations in the Physical Medicine & Functional Rehabilitation Department and the Endocrinology Department in the week preceding programme initiation and in the week following the end of the programme for G2 and G3. In G1, the evaluation was performed at the start of the protocol and after two months.

1.3.1.1

Evaluation of anthropometric parameters

We evaluated a number of anthropometric parameters: weight, height, BMI and waistline measurement (WL). For the evaluation of body fat mass, body lean mass and basal metabolic rate, we used an impedance meter (the TBF 300 from TANITA ® ).

1.3.1.2

Evaluation of the cardiovascular impact of obesity

The cardiovascular impact of obesity in each patient was assessed using a treadmill stress test (ST) (on a Tmo ® MEDICAL) based on a modified Bruce protocol . Throughout the ST, a Polar Tempo system continuously monitored the HR in beats per minute (bpm) . Arterial blood pressure was measured at rest and at the end of each 3-minute step using a sphygmomanometer (Spengler). For patients with associated arterial hypertension (AHT), the ST was performed in the presence of a cardiologist. The parameters monitored during the ST were as follows: the HR at rest (HR r ), at maximum effort (HR max ) and at the end of each 3-minute step, the systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) arterial blood pressure values at rest, at maximum effort and at the end of each step and the total duration of the ST.

1.3.1.3

Evaluation of muscle strength

For the initial and final evaluations of arm and leg muscle strength, we sought to determine the maximum repetition (MR1), which is the highest single load in kilograms that the patient can move in a full-amplitude repetition. This measurement was performed for the depressor muscles of the shoulder, the elbow flexors & extensors, the gluteus maximus & medius and the knee flexors & extensors. The final value was the average of three measurements on the strongest body side. The MR1 was measured at the start of each week in order to readjust the intensity of the strength training for each muscle group.

1.3.1.4

Evaluation of metabolic disorders

At the start and the end of the protocol, all the patients were assayed for fasting glycaemia, total cholesterol, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol. We calculated the LDL cholesterol level according to the Friedwald-Fredrickson equation .

1.3.1.5

Evaluation of dyspnoea during activities of daily living

At the start and the end of the protocol, the intensity of dyspnoea during activities of daily living was assessed to the nearest millimetre on a dyspnoea visual analogue scale (VAS) graduated from 0 to 100 mm (where 0 represents the absence of dyspnoea and 100 represents the most intense dyspnoea imaginable).

1.3.1.6

Evaluation of the psychological impact of obesity

We evaluated the patients’ psychological status during the study by using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) questionnaire . This scale has two columns: column A for anxiety and column D for depression. The maximum score possible for each column is 21. A score per column of between 8 and 10 is suggestive of an anxious or depressive state and a score of 11 or more indicates the highly probable presence of an anxious or depressive state.

1.3.1.7

Evaluation of quality of life

Quality of life was evaluated using an Arabic version of the impact of weight on quality of life (IWQOL) lite .

The translation of the questionnaire and adaptation of certain items yields a scale with five domains: physical function, self-esteem, sexual life, public distress relationships and work.

The score from each item is then reported as a percentage of the maximum possible score, giving a value of between 0 and 100. A score below 80% indicates that quality of life is altered and the lower the score, the more quality of life is affected.

1.3.2

Obesity management methods

1.3.2.1

Prescribed diets

The interview-based food survey was performed for all patients by dieticians in the Endocrinology Department, with the objective of specifying previous food habits and possible anomalies in dietary behaviour. Data was recorded using a week-long daily food diary and the BILNUT software package (1991 version).

A 25 to 30% decrease in calorie intake (relative to previous levels) was applied in most cases. The prescribed low calorie diet was balanced, with 15% as protein, 30 to 35% as fat and 50 to 55% as carbohydrate, on average. We checked that food was eaten as three daily meals and we emphasized the need to have a substantial breakfast.

All three groups underwent an identical dietary monitoring programme, with an initial consultation, a check-up in the middle of the programme and another during the final sessions by an Endocrinology Department dietician who was blinded to the type of the programme that the subject had been following.

1.3.2.2

The physical training programmes

All our patients were advised to start their diet and lose 2 to 3 kg before starting the physical training sessions.

1.3.2.2.1

The aerobic, treadmill-based training programme

The intensity of the aerobic, treadmill-based training programme (on a Tmo ® MEDICAL) was set to 60% of the HR max achieved in a reference ST performed according to a modified Bruce protocol. This rate was defined as the training heart rate (THR).

As a result of training-induced improvements, a given HR no longer corresponded to the same load level as the sessions went by; this is why the speed (in km/h) was increased, while keeping the same THR intensity.

After an initial, 5-minute warm-up phase performed on the treadmill at a low load, each endurance training session lasted 30 minutes and ended with 5-minute recovery and relaxation phase.

All patients performed three weekly sessions (i.e. a total of 24 sessions per patient over a 2-month period. Cardiovascular parameters were monitored by a study nurse, who noted the arterial blood pressure and the HR in a study diary every five minutes during the session.

1.3.2.2.2

Limb muscle strength training

In addition to the treadmill training, limb muscle strength training exercises were performed in G3. These were dynamic exercises of the legs, arms and the abdominal wall muscles related to the work of respiration.

The arm muscle exercises concerned the depressor muscles of the shoulder and the elbow extensors and flexors.

In general, the strength training was performed at 60% of the maximal voluntary force (MVF, re-evaluated at the start of each week in order to adjust the intensity). For each muscle group, the patient performs three series of 20 repetitions, with a one-minute break between series.

The leg muscle exercises were performed according to the same procedures and concerned the gluteus maximus, the gluteus medius and the knee extensors and flexors.

1.3.2.2.3

Monitoring of additional physical activity during the week

As part of our patient management programme, we encouraged complementary walking activity (non stop walking for 40 to 60 minutes 3 times a week) and we checked compliance at the start of each training session by asking our patients how much time they had spent walking and how far they had walked.

Compliance with the complementary physical activity programme was considered to be excellent for patients having walked non stop for 40 to 60 minutes three times a week, good for the patients having walked non stop for 40–60 minutes à reason of two times a week, average for the patients having walked non stop for 40–60 minutes once a week and poor for the patients who did not reach the latter duration and quality target.

1.4

Statistical study

We mainly used the Chi-squared test, an analysis of variance (ANOVA), regression and a pair-wise comparison test for paired samples.

SPSS ® software (version 13) was used to code the data report forms and perform the various statistical tests.

Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to study the relationship between binary variables, with a statistical significance threshold set to p < 0.05.

A one-factor ANOVA was used to perform a univariate analysis of variance for a quantitative, dependant factor and another independent factor. It tests the null hypothesis whereby the mean is the same for all groups.

Lastly, a T-test for paired samples was used to study the change over time in the patients’ various clinical and biochemical parameters before and after the training period.

1.5

Results

All our patients had managed to lose between 2 and 3 kg before starting the programme. The weight loss was, on average, 2.45 kg in G1, 2.50 kg in G2 and 2.45 kg in G3 ( p = NS).

1.5.1

Epidemiological characteristics and evaluation of the impact of obesity

The mean ± standard deviation age of the study population (comprising 13 men [15.6%] and 70 women [84.4%]) was 37.2 ± 10 (range: 18 to 60). The patients had been obese for 9.5 ± 6 years (range: 3 to 20). The average body weight was 99.7 ± 17.5 kg (range: 76 to 148). The average BMI was 37.2 ± 5.2 kg/m 2 (range: 30 to 53.8 kg/m 2 ). Body fat mass was 41.95 ± 7.7 kg (i.e. 41% of body weight), the lean mass was 53.5 ± 7.5 kg and the basal metabolic rate was 1742.62 ± 203 Kcal/d. Our population included 23 hypertensive patients, 12 patients with dyslipidaemia and 17 diabetics.

Table 1 summarizes and compares the three study groups’ epidemiological and anthropometric characteristics.

| G1 | G2 | G3 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38 ± 10 | 36.1 ± 12 | 37.5 ± 8 | NS |

| Gender (M/F) | 5/24 | 4/22 | 4/24 | NS |

| Antecedents | ||||

| Diabetes | 5 | 7 | 5 | NS |

| Dyslipidaemia | 3 | 4 | 5 | NS |

| AHT | 6 | 8 | 9 | NS |

| Duration (years) | 10 ± 5.73 | 9 ± 5.8 | 9.6 ± 6.5 | NS |

| Weight (kg) | 103.4 ± 21.6 | 99.2 ± 18 | 96.3 ± 10.9 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 38.2 ± 4.9 | 37.3 ± 6.7 | 36 ± 3.86 | NS |

| WL (cm) | 113.69 ± 14.4 | 112.34 ± 20.11 | 110.65 ± 8.8 | NS |

Tables 2–4 illustrate the results for the cardiovascular, muscle-related and metabolic impact of obesity and compares the three study groups.

| G1 | G2 | G3 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting HR | 83 | 86.2 | 79 | NS |

| HR at maximum effort | 148.5 | 150.8 | 140.8 | NS |

| Resting systolic/diastolic BP | 127.8/72.7 | 127/79.2 | 130.3/75.7 | NS |

| Systolic/diastolic BP at maximum effort | 178.1/87.5 | 168.4/87.5 | 172.5/90 | NS |

| Total duration of stress test | 10 min | 10 min 25 s | 11 min 13 s | NS |

| Muscle group | G2 (kg) | G3 (kg) | G1 (kg) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoulder depressors | 8.9 ± 2.6 | 9.9 ± 1.5 | 9.4 ± 2.2 | NS |

| Elbow flexors | 8.7 ± 1.4 | 7.4 ± 3.6 | 8 ± 2.9 | NS |

| Elbow extensors | 7.4 ± 1.8 | 6.8 ± 1.4 | 7.1 ± 1.7 | NS |

| Gluteus maximus | 6.7 ± 1.7 | 7.57 ± 2.2 | 7.1 ± 2 | NS |

| Gluteus medius | 7.2 ± 2 | 6 ± 2.5 | 6.5 ± 2.3 | NS |

| Knee extensors | 14.1 ± 1.7 | 14.6 ± 1.8 | 14.4 ± 1.7 | NS |

| Knee flexors | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 6.9 ± 2 | 6.6 ± 1.7 | NS |

| G1 | G2 | G3 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol | ||||

| Total (mmol/l) | 4.75 | 5.15 | 4.96 | NS |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.57 | NS |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 2.86 | 2.17 | 2.11 | NS |

| Triglycerides mmol/l | 1.35 | 1.12 | 1.45 | NS |

| Fasting glycaemia mmol/l | 5.7 | 5.8 | 6.03 | NS |

In terms of the patients’ psychological status, the average scores on the HAD scale were 11.8 ± 2.75 out of 21 for anxiety and 9.6 ± 3.2 out of 21 for depression. Seventeen patients (22%) had clinical depression and 22 (29%) suffered from anxiety disorders.

The impact of obesity on the quality of life was evaluated in all our patients on the IWQOL lite scale and yielded an average overall score of 65.2 ± 15.8. The average domain scores were 30.4 ± 9.8 for physical function, 15.4 ± 6.3 for self-esteem, 7.17 ± 3.5 for sexual life, 8.7 ± 3.6 for public distress and 8.46 ± 3.6 for the work.

1.5.2

Obesity management measures

1.5.2.1

The patients’ dietary characteristics

The patients’ initial daily calorie intake was 2162 ± 646.94 Kcal/d (range: 1080 to 4368).

After the training period, this intake had fallen in most of our patients and averaged 1622.22 ± 298.67 Kcal/d (range: 1200 to 2000); this corresponds to an average reduction of 540 ± 420 Kcal.

The patients’ recommended diet had mean carbohydrate, lipid and protein contents of 55.6 ± 6.5%, 29.3 ± 6.4% and 16.1 ± 2.1%, respectively.

1.5.2.2

Physical exercise parameters

The average THR calculated in our patients was 87 ± 25 bpm. The HR actually maintained by our patients during training sessions averaged 112 ± 31 bpm.

1.5.2.3

Follow-up of extraphysical activity in daily life

Extraphysical activity during daily life was only monitored in trained patients; 24 patients (52%) showed excellent compliance, 14 (30.5%) showed good compliance; 6 (13%) displayed average compliance and only 2 (4.5%) had poor compliance.

At the start of the training period, the three groups did not differ significantly in terms of the various parameters studied, i.e. their epidemiological and anthropometric characteristics and the impact of obesity (Tables 1–6 and 8) .

1.5.3

Change over time in the evaluated parameters before and after training

1.5.3.1

Change over time in anthropometric characteristics

The most significant weight loss was observed in G3 (with a mean reduction of 7.24%), followed by G2 (4.27%). The percentage weight loss in G1 was only 0.16%.

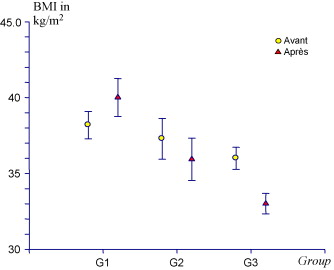

For BMI, the mean values changed from 37.47 ± 6.97 to 35.58 ± 6.85 kg/m 2 in G2 (a 5% decrease), from 36 ± 3.8 to 33 ± 3.85 kg/m 2 in G3 (a 8.33% decrease) and from 38.9 ± 4.5 to 40.2 ± 6.2 kg/m 2 in G1 (a 3.3% increase).

These variations were highly significant in G2 and G3 ( p < 0.001) and non significant in G1.

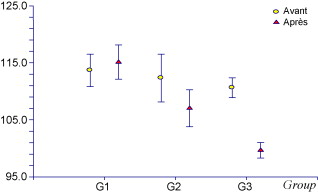

A decrease in WL was observed in G2 and G3; the value fell from 112.3 ± 20.11 cm to 107.45 ± 15.48 cm in G2 (a 4.85 cm decrease) and from 110.65 ± 8.79 cm to 100.34 ± 7.03 cm in G3 (a 10.3 cm decrease). The percentage decreases (4.3% in G2 and 10.26% in G3) were highly significant ( p < 0.001) in the two trained groups, compared with the control group.

No WL decrease was seen in G1; in fact, the mean value increased from 115.43 ± 13.04 cm to 116.27 ± 13.63 cm (NS).

All the data concerning BMI and WL are presented in Figs. 1 and 2 .

1.5.3.2

Change over time in the impedancemetry results

The percentage improvement in body fat mass was 10.4% in G3 ( p < 0.001), 8.6% in G2 ( p = 0.03) and 0.4% in G1 (NS).

The lean mass changes were not significant in G1 and G2. However, we noted a significant ( p = 0.02) increase in G3 (4.7%).

Table 5 summarises the impedancemetry data for the three groups.

| G1 (kg) | G2 (kg) | G3 (kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty mass | |||

| Before | 44.4 ± 4.97 | 44.7 ± 7.91 | 39.92 ± 9.03 |

| After | 44.58 ± 4.65 | 40.84 ± 9.77 | 35.74 ± 9.41 |

| p | NS | 0.032 | < 0.001 |

| Lean mass | |||

| Before | 52.93 ± 9.07 | 55.91 ± 10.6 | 53.19 ± 5.76 |

| After | 52.9 ± 8.98 | 56.68 ± 12.4 | 55.68 ± 8.31 |

| p | NS | NS | 0.02 |

| Basal metabolism | |||

| Before | 1784 ± 176 | 1828 ± 339 | 1698 ± 188 |

| After | 1726 ± 171 | 1842 ± 337 | 1793 ± 275 |

| p | NS | NS | 0.026 |

1.5.3.3

Change over time in stress test parameters

We noted an improvement in physical condition in the trained groups G2 and G3; this was notably expressed as (a) a 9.8% decrease in resting HR in G2 ( p = 0.02) and a 12.9% decrease in G3 ( p < 0.001) and (b) a 10.9% decrease in resting DBP in G2 ( p = 0.05) and a 15.5% decrease in G3 ( p < 0.001).

Similarly, we observed an improvement in the maximum effort parameters, with (a) an 8.9% decrease in HR max in G2 ( p = 0.009) and an 8.5% decrease ( p = 0.008) in G3 and (b) a 7.8% decrease in SBP at maximum effort for the same given step in G2 ( p = 0.001) and a 10.8% decrease in G3 ( p < 0.001).

The changes over time in all ST parameters are illustrated in Table 6 .

| Resting heart rate in bpm | Heart rate at maximum effort in bpm | Resting systolic BP in mmHg | Systolic BP at maximum effort in mmHg | Resting diastolic BP in mmHg | Diastolic BP at maximum effort in mmHg | Duration of the ST in minutes | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | p | Before | After | p | Before | After | p | Before | After | p | Before | After | p | Before | After | p | Before | After | P | |

| G3 | 79.03 | 68.78 | < 0.001 | 140.78 | 128.75 | 0.008 | 130.3 | 113.5 | < 0.001 | 172.5 | 153.8 | < 0.001 | 75.7 | 63.9 | < 0.001 | 95.9 | 84.6 | < 0.001 | 11 min 31 | 14 min 22 | < 0.001 |

| G2 | 86.2 | 77.72 | 0.025 | 150.84 | 137.40 | 0.009 | 127 | 118 | 0.002 | 168.7 | 155.4 | 0.001 | 78.6 | 70 | 0.05 | 89 | 82.3 | 0.007 | 10 min 25 s | 12 min 27 s | < 0.001 |

| G1 | 82.95 | 81.45 | NS | 147.75 | 146.55 | NS | 127.8 | 128.8 | NS | 171.8 | 184.7 | 0.017 | 72.7 | 69.6 | NS | 87.5 | 85.5 | NS | 10 min 05 s | 10 min 05 s | NS |

1.5.3.4

Change over time in muscle strength

After training, we noted a clear improvement in muscle strength (especially arm strength) in G2 and G3.

The overall improvement in muscle strength was 37.5% for the arms and 34.7% in the legs. In G2, this improvement was 23.9% for the arms and 28.2% for the legs. In G3, the improvement was 51% for the arms and 41.2% for the legs.

The groups’ percentage variations in maximum strength (when comparing the start and the end of the programme are presented) in Table 7 .

| Muscle group | Overall | Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G2 (%) | G3 (%) | p | G2 (%) | G3 (%) | G2 (%) | G3 (%) | |

| Shoulder depressors | 22.9 | 41.2 | 0.04 | 25 | 41.7 | 18 | 38.5 |

| Elbow flexors | 30 | 71 | 0.002 | 26.3 | 71 | 37.9 | 70 |

| Elbow extensors | 18.8 | 41 | 0.04 | 19 | 46 | 17 | 17 |

| Gluteus maximus | 32.2 | 56.5 | 0.02 | 44 | 61 | 30 | 50 |

| Gluteus medius | 27.3 | 38.3 | 0.05 | 29 | 54 | 13 | 35 |

| Knee extensors | 26.2 | 34.5 | 0.004 | 32 | 37 | 25 | 33 |

| Knee flexors | 27.2 | 35.2 | 0.006 | 24 | 31 | 27 | 35 |

1.5.3.5

Change over time in clinical biochemistry parameters

1.5.3.5.1

Change over time in fasting glycaemia values

The percentage improvement was similar in G2 and G3 (9.6 and 8.6%, respectively). In contrast, it was much lower (3%) and non significant in G1.

1.5.3.5.2

Change over time in triglyceride (TG) levels

A post-training decrease in TG was seen in G2 and G3 but was absent and thus non significant in G1. The degree of improvement was similar in the trained groups (34% in G2 and 29.7% in G3), with a pooled average of 32%.

1.5.3.5.3

Change over time in HDL and LDL cholesterol levels

After eight weeks, we noted a significant increase in HDL cholesterol in the trained groups (12% in G2 and 14% in G3). In G1, the change was not significant.

The changes in the lipid profile parameters are presented in Table 8 .

| G1 | G2 | G3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TG | |||

| Before | 1.45 ± 0.45 | 1.45 ± 0.71 | 1.55 ± 0.73 |

| After | 1.19 ± 0.43 | 0.98 ± 0.32 | 1.09 ± 0.56 |

| p | NS | 0.08 | < 0.001 |

| Cholesterol | |||

| Total before | 4.43 ± 1.86 | 5.59 ± 0.99 | 5.08 ± 1.43 |

| Total after | 4.89 ± 1.71 | 4.99 ± 0.84 | 4.61 ± 1.17 |

| p | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| LDL before | 2.86 ± 0.99 | 2.17 ± 0.55 | 0.55 ± 0.21 |

| LDL after | 2.77 ± 1.03 | 1.87 ± 1.14 | 0.78 ± 0.32 |

| p | NS | 0.005 | 0.001 |

| HDL before | 0.55 ± 0.19 | 0.57 ± 0.3 | 0.56 ± 0.12 |

| HDL after | 0.57 ± 0.19 | 0.64 ± 0.15 | 0.64 ± 0.12 |

| Glycaemia | |||

| Before | 5.7 ± 0.45 | 5.8 ± 0.71 | 6.03 ± 0.73 |

| After | 5.9 ± 0.43 | 5.24 ± 0.32 | 5.51 ± 0.56 |

| p | NS | 0.08 | < 0.001 |

1.5.3.5.4

Change over time in dyspnoea

The sensation of dyspnoea during effort (as measured on the dyspnoea VAS), fell from 45.8 ± 33.5 to 43.1 ± 33.7 mm in G1 ( p = NS), from 54.6 ± 24 to 22.5 ± 18 mm in G2 (a 58.7% improvement, p < 0.001) and from 49.2 ± 23.5 to 18.6 ± 10 mm in G3 (a 62% improvement, p < 0.001).

1.5.3.5.5

Change over time in psychological status

We noted an improvement in the anxiety score on the HAD scale in the trained groups; the mean value fell from 12 ± 1.8 to 8.3 ± 2.7 in G3 (a 30% improvement, p < 0.001) and from 12.34 ± 1.67 to 9.92 ± 3.4 in G2 (a 19% improvement, p < 0.001). No change in the anxiety score was seen in G1, with scores of 10.51 ± 2.3 and then 10.58 ± 2.4 ( p = NS).

Likewise, we observed an improvement in the depression score on the HAD scale in the trained groups, with mean values falling from 9.4 ± 2.7 to 4.9 ± 1.7 in G3 (a 47% improvement, p < 0.001) and from 8.8 ± 4.2 to 5.6 ± 3.4 in G2 (a 36% improvement, p = 0.002). No improvement in depression was seen in G1, with a slight and non significant decrease from 10.5 ± 2.4 to 9.7 ± 2.9 in G1.

1.5.3.5.6

Change over time in quality of life

We noted a significant improvement in the IWQOL lite quality of life scores in the trained groups (15.2% and 18% for G2 and G3, respectively). The improvement was seen in all domains of the scale ( Table 9 ). The score did not change significantly in G1.

| G1 | G2 | G3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | Before | 49.34 | 42.87 | 40.31 |

| After | 48.9 | 55.21 | 63.24 | |

| Improvement (%) | 0.89 | 28.78 | 56.88 | |

| p | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Self-esteem | Before | 57.34 | 49.77 | 59.75 |

| After | 57.83 | 66.61 | 66.33 | |

| Improvement (%) | 0.85 | 33.83 | 11.01 | |

| p | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Sexual life | Before | 67.6 | 62.65 | 60.9 |

| After | 67.41 | 66.84 | 71.13 | |

| Improvement (%) | 0.27 | 6.68 | 16.8 | |

| p | NS | 0.009 | < 0.001 | |

| Public distress | Before | 64.41 | 64.84 | 65.73 |

| After | 65.65 | 69.47 | 70.08 | |

| Improvement (%) | 1.92 | 7.14 | 6.66 | |

| p | NS | 0.043 | < 0.001 | |

| Work | Before | 56.55 | 54.73 | 61.52 |

| After | 57.75 | 58.68 | 68.47 | |

| Improvement (%) | 2.12 | 7.22 | 11.29 | |

| p | NS | 0.04 | <0.001 | |

| Total score | Before | 59.04 | 54.97 | 57.48 |

| After | 59.5 | 63.36 | 67.85 | |

| Improvement (%) | 0.79 | 15.26 | 18.04 | |

| p | NS | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

1.6

Discussion

The management of obesity essentially consists of dietary measures and increased physical activity.

A food survey was the first step in our care programme and gave us an idea of the patients’ food habits in the broadest sense: their tastes, preferences, rhythms, cooking styles, mealtimes and family context and the place where meals were taken. The prescribed low-calorie diet introduced an energy shortfall of 500 to 600 kcal/day (2092 to 2510 KJ/day) that the patients had to seek to maintain over the long term. When applied correctly, this method enables greater weight loss over time than much more restrictive diets . This is the diet that is most prescribed in combination with physical training in the literature . Overall, the diet was low in fat and carbohydrate-rich .

The physical training per se included two types of exercise: aerobic treadmill training and segmental strength training of the arm, leg and abdominal wall muscles. The aerobic treadmill training involved supervised, 45- to 60-minute exercise sessions three times a week. Many studies have shown that this type of activity presents significant advantages but is difficult to maintain over time in obese subjects . In fact, a high proportion of our patients were not able to comply diligently with the 2-month programme. Most of these subjects gave up with the first few weeks and thus were excluded from the study. For our patients, we used just 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise (at 60% of the HR max measured in an ST) on a treadmill three times a week.

Regarding the characteristics of physical activity, a report by the US Surgeon General has emphasized the fact that prolonged, low-intensity physical activity (for example, a brisk 30- to 60-minute walk nearly every day, for example) significantly increases energy expenditure and reduce body fat mass and bodyweight. This type of exercise also enables maintenance of weight loss .

The exercise intensity (the key parameter) can be expressed as a percentage of the maximum oxygen consumption ( V O 2 max) or as a percentage of the HR max measured during a ST. In our series, we used the latter parameter, measured according to a modified Bruce protocol. The THR calculated from the HR max was 87 bpm on average, whereas the HR actually maintained during the training sessions was somewhat higher, at 112 bpm.

The type of variable exercise has been performed on a treadmill in some series and on an electromagnetic cycle ergometer in others . A combination of the two is also possible . The type of exercise used is chosen according to the subjects’ healthcare constraints .

Peripheral, segmental muscle strength training is a method which has already been used in the obese (either alone or in combination with aerobic exercise). Arm and leg muscle groups may both be involved and the exact protocol varies from one series to another .

Although the beneficial effect of physical training has been widely documented, the characteristics of this exercise are not well codified. In fact, to maximise weight loss, the beneficial effect of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week has been long known , although some recent studies support a hypothesis whereby a longer duration of physical activity improves the long-term weight loss results. In fact, some people need additional exercise or a greater degree of calorie restriction to reduce the probability of weight regain . These parameters are supported by the physical activity position statements issued by the Institute of Medicine , the American College of Sports Medicine and the International Association for the Study of Obesity . From these data, it appears that the best programme for the obese is to start with 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity exercise and then progressively increase the duration of the sessions or introduce additional activity outside the sessions. In our study, we obtained significant weight loss with only 120 minutes a week. This can be explained by not only good patient compliance with dietary measures but also performance of additional walking activity during the week. Weight loss was greater in G3, whose members exercised for 180 minutes a week.

In our series, we noted greater overall weight loss (6.68 kg, i.e. 0.83 kg per week) in the group having undertaken an hour of exercise (G3), compared with the group having undertaken only 30 minutes (G2, with 4.23 kg, i.e. 0.52 kg per week).

Likewise, the loss of body fat mass was 4.4 kg in G3 and 3.86 kg in G2.

In the literature, the degree of weight loss varies from one study to another. In fact, our results are lower than those reported by Sartorio et al. , who noted a weight loss of around 4.4 kg (1.46 kg/week) after three weeks of dieting, aerobic training and segmental muscle strength exercises. Likewise, Lejeune et al. reported a weight loss of about 1.15 kg per week after 13 weeks of dieting, physical training and aquarobics. Our results are in agreement with those of Melason et al. , who noted an average weight loss of 0.575 kg per week after physical training and dieting.

In general, one can consider that that the 75% of weight loss is represented by fatty mass , independently of age and ethnic origin. In our series, the weight loss in both G2 and G3 was essentially due to body fat loss. Our results are similar to those reported by Maffiuletti et al. and Melanson et al. , who noted decreases of 6.9 and 15.6%, respectively.

The weight loss induced by a calorie-restricted diet not only corresponds to fatty mass but it also related to lean body mass, 20% of which consists of muscle protein. The extent of protein loss depends on many factors, including (notably) the size of the calorie shortfall, the diet’s composition and duration and the degree of obesity. Adding regular physical activity to the calorie restriction may limit this phenomenon. In fact, in a meta-analysis of 46 studies , it seems that the addition of physical exercise to a diet is accompanied by lower lean body mass loss (compared with a diet-only programme), whereas the overall weight loss and the fatty mass loss are unchanged . However, the possible effect of physical activity on the lean body mass is subject to debate; more rigorous, in-depth studies are needed to clarify this point .

In our series, we did not note any variations in lean mass in the patients having performed aerobic treadmill training; in contrast, patients having performed additional strength exercises displayed an increase in lean mass and a greater decrease in fatty mass. These observations emphasize the beneficial effect of strength exercises in the management of obesity.

The abdominal distribution of body fat (assessed in terms of the waistline measurement) has been extensively studied . It has been difficult to determine the influence of training programmes of varying intensity and duration on abdominal fat. In our series, we noted a clear decrease in WL (about 7 centimetres, on average) in the trained group after eight weeks of exercise. This improvement was much higher in the group having performed additional muscle strength exercises and out results are in agreement with those of Melanson et al. , Ross et al. and Shadid et al. .

In haemodynamic terms, we know that physical training improves physical condition and resistance to effort, regardless of gender and age. According to Vuori , greater resistance to effort enables obese subjects to progressively increase the intensity of their physical training in absolute terms (while remaining at the same relative level of intensity) and thus augment their energy expenditure.

In our series, we noted a decrease in the resting HR and HR max . The training effect was similar in G2 and G3 and our results are in line with the findings of various studies, such as those by Wadden et al. and Melanson et al. .

The beneficial effect of physical training on blood pressure values in the obese has been widely discussed. In fact, the published meta-analyses of studies performed on normal weight subjects and overweight and obese subjects have all confirmed that physical activity decreases systolic/diastolic arterial blood pressure by an average of around 7.4 mmHg/5.8 mmHg and that exercise at the aerobic threshold and power training both decrease arterial blood pressure values.

Few studies have compared the benefits of different physical training programmes on muscle strength in obese and overweight people .

In our series, we noted an increase in muscle strength (for both the arms and legs) in all the trained patients. This increase was much higher in the group which had undergone segmental muscle strength exercises (G3) than in the treadmill-only group (G2). The difference between G2 and G3 in terms of the MR1 improvement was greater for the arm muscles. Our results are similar to those of Brooks et al. and Kirk et al. , who respectively noted increases of 36 and 31.3% in arm muscle strength, as evaluated by the manual MR1 method. However, for the legs, the results are very divergent and range from 17% in the series reported by Kirk et al. to 68% in the series reported by Brooks et al. . This high variation is essentially due to differences between the strength training protocols.

A decrease in glycaemia after moderate-intensity exercise has already been reported in the obese and in type II diabetics . The amplitude of the decrease in glycaemia is related to the exercise duration and intensity , the initial glycaemia value and the time since initiation of the physical activity . Exercise intensity seems to play a role in the regulation of glycaemia. In fact, moderate-intensity exercise decreases glycaemia and this effect can even last beyond the period of exercise . In our series, we noticed a similar decrease (9.5%) in glycaemia in both the trained groups. There was no decrease in the control group. Our data are similar to those from previously published studies . The addition of strength exercises does not seem to potentiate this effect.

Data on the effects of exercise in obese individuals with poor lipoprotein profiles are extremely scarce . Physical exercise and dietary measures both increase HDL cholesterol levels and decrease triglycerides and LDL cholesterol levels significantly. These modifications are even greater in obesity and dyslipidaemia . In the present study, the degree of improvement was similar in the two trained groups. Our results are in agreement with literature data on changes in TG, total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol . However, we note that our HDL cholesterol results were more marked than in other studies; this may be explained by the extent of the weight loss in our series, the role of genetic and ethnic factors or the Mediterranean-style diet.

A positive effect of physical exercise on anxiety in the obese has been reported by several authors .

In our series, we noted a clear improvement in the anxiety score in both trained groups. The decrease was about 23% in G2 but was greater (35%) in the strength training group (G3).

The relationship between obesity and depression has been extensively reported in the NHANES III study, which showed that major depression was frequent in obese women (mainly those with a BMI > 40) .

Although there are few studies of obese patients , the positive effect of training programmes has also been noted in both obese and overweight subjects. In our series, an improvement in the HAD depression score of about 19% was observed in G2 and was even greater (30%) in the strength training group (G3).

An improvement in mood and quality of life in obese patients having undertaken weight loss programmes including physical exercise has been reported by a number of studies . In our series, the improvement in the quality of life score was greater in G3 (18%) than in G2 (15.2%). Hence, quality of life improved more in the strength-training group and this was clearest in the physical function domain. Analysis of studies involving peripheral muscle strength training exercises has shown a (a) gain in physical function due to an improvement in the performance of strength-requiring tasks, such as climbing stairs or standing up from a chair or from a crouched position and (b) the absence of an improvement in activities associated with endurance (such as balance), in both obese and normal-weight subjects .

1.7

Conclusion

Our study has demonstrated the beneficial effect of a combination of dietary measures with physical training in the management of obesity. This type of programme resulted in weight loss, a decrease in fatty mass and abdominal fat, correction of the metabolic disorders frequently associated with obesity and thus a reduction in cardiovascular risk factors.

The obesity management programme also produced an increase in the obese patients’ physical capacities, with improvements in all the ST parameters: HR and the arterial blood pressure at rest and at maximum effort and the total duration of the ST.

The improvement in all these parameters boosted psychological status and quality of life in the obese subjects studied here.

Regarding the comparability of two protocols of physical physical training, we noted that the combination of endurance and strength exercises produced a more notable improvement in certain parameters – weight loss, muscle strength (mainly in the arms) and waistline. Likewise, we observed a more marked improvement in psychological status and quality of life.

Although the inclusion of muscle strength exercises does not result in an obvious improvement in cardiovascular parameters (HR, the total duration of the ST and the dyspnoea VAS score), it appears to be a useful addition to physical training protocols for the obese.

Hence, we believe that further studies with larger populations and different protocols should be performed in order to prove the beneficial effect of combining dietary measures and physical training and to identify the most appropriate programme for the management of obesity and its complications.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’obésité est une pathologie fréquente ayant de nombreuses complications la rendant depuis ces 20 dernières années, de plus en plus inquiétante aussi bien dans les pays occidentaux qu’en voie de développement .

L’obésité doit être considérée comme une maladie à part entière. Elle peut également être un facteur de risque d’autres maladies à travers la surcharge pondérale et les troubles métaboliques généralement associés. En effet, les maladies cardiovasculaires mettant en jeu le pronostic vital. Les pathologies articulaires mettant en jeu le pronostic fonctionnel et la souffrance morale engendrant des comportements pathologiques, peuvent être la conséquence de l’obésité. Cette cohorte de comorbidités associée à l’altération psychologique abaisse fortement la qualité de vie , d’où la nécessité d’une prise en charge multidisciplinaire précoce . Le traitement médical de l’obésité repose sur une combinaison de mesures thérapeutiques à savoir l’activité physique, la prise en charge diététique et le soutien psychologique. La prise en charge de l’obésité par les différents moyens à court et à long terme a fait l’objet de plusieurs métanalyses . Cette prise en charge est nécessaire car elle permet, en plus de la réduction de la surcharge pondérale , une amélioration des différents paramètres tels que les facteurs de risque cardiovasculaires , les troubles métaboliques , le retentissement fonctionnel et psychologique ce qui permet de garantir une meilleure qualité de vie . Le but de notre travail était de déterminer en premier lieu, l’apport du réentraînement à l’effort associé à la diététique chez une population d’adultes obèses aussi bien sur les paramètres métaboliques, cardiovasculaires, psychologiques que sur la qualité de vie, par rapport à un groupe témoin. Le second objectif de notre travail était de comparer deux types de protocoles de réentraînement à l’effort chez l’obèse.

2.2

Patients et méthodes

2.2.1

Patients

Il s’agit d’une étude prospective randomisée, allant de juillet 2004 à novembre 2007 ayant inclus les patients obèses avec un indice de masse corporelle (IMC) supérieur ou égal à 30 kg/m 2 , adressés du service d’endocrinologie à l’unité de réadaptation à l’effort du service de médecine physique rééducation et réadaptation fonctionnelle de Sfax. Tous les patients étaient traités en ambulatoire.

Nous avons exclu de l’étude les patients qui présentaient une contre-indication à l’effort, un problème orthopédique majeur rendant la marche sur tapis roulant impossible (gonarthrose invalidante), des troubles psychiatriques graves, des antécédents de maladie cardiaque et/ou un infarctus du myocarde récent, les patients non consentant au protocole, ainsi que ceux n’ayant pas suivi avec assiduité les huit semaines consécutives de réentraînement à l’effort.

Tous les patients ont bénéficié d’une enquête alimentaire, suivie d’une prescription de régime.

Nous avons recruté 152 patients obèses désadaptés à l’effort. Seulement 83 patients ont été retenus pour l’étude. Les 69 patients restants n’ont pas pu suivre avec assiduité le protocole de réadaptation pour un problème de santé quelconque ou pour un problème d’éloignement de leur domicile et ont été exclus de l’étude.

Tous les patients ont été randomisés en trois groupes. Les groupes étaient initialement de 50 pour G1 et de 51 pour G2 et G3 en considérant les patients exclus soit 21 patients dans le G1, 25 patients dans le G2 et 23 patients dans le G3, les patients qui étaient évalué au début et à la fin du protocole étaient repartis comme suit :

- •

un premier groupe (G1) ou groupe témoin de 29 patients comportant les patients n’ayant bénéficié ni de conseils hygiénodiététiques ni d’exercice physique ;

- •

un deuxième groupe (G2) de 26 patients comportant les patients qui ont suivi en plus des conseils hygiénodiététiques, un programme de réentraînement à l’effort avec des exercices de type aérobie sur tapis roulant ;

- •

un troisième groupe (G3) de 28 patients comportant les patients qui ont suivi des conseils hygiénodiététiques, un programme de réentraînement à l’effort de type aérobie sur tapis roulant associé à des exercices de renforcement musculaire segmentaire des quatre membres.

2.3

Méthodes

2.3.1

Les paramètres d’évaluation

Tous les patients ont été évalués au sein de deux consultations spécialisées dans le service de médecine physique, rééducation et réadaptation fonctionnelle, et le service d’endocrinologie, dans la semaine précédant la prise en charge, et dans la semaine suivant la fin du protocole pour les groupes G2 et G3. Pour le G1, l’évaluation a été réalisée au début du protocole et après deux mois.

2.3.1.1

Évaluation des paramètres anthropométriques

L’évaluation a concerné les paramètres anthropométriques à savoir le poids, la taille, l’IMC, le tour de taille (TT). Pour l’évaluation de la masse maigre et de la masse grasse ainsi que le métabolisme de base, nous avons utilisé un impédencemétre type TANITA ® modèle TBF 300.

2.3.1.2

Évaluation du retentissement cardiovasculaire de l’obésité

Le retentissement cardiovasculaire de l’obésité a été apprécié grâce aux données d’une épreuve d’effort (EE) réalisée systématiquement chez tous nos patients selon le protocole de « Bruce modifié » en utilisant un tapis roulant de type Tmo ® MEDICAL. Durant toute l’épreuve, le moniteur relevait la fréquence cardiaque en pulsations par minute (batt/min) en permanence à l’aide d’un système Polar Tempo . Une prise de la tension artérielle a été réalisée au repos, à la fin de chaque palier de trois minutes à l’aide d’un sphygmomanomètre (Spengler). Cette épreuve était réalisée avec la présence d’un cardiologue chez les patients ayant un problème d’hypertension artérielle (HTA) associée. Les paramètres recueillis de l’EE étaient : la fréquence cardiaque de repos (FCr), à l’effort maximal (FC max ) et à la fin de chaque palier de trois minutes, la tension artérielle systolique (TAS) et diastolique (TAD) au repos, à l’effort maximal et à la fin de chaque palier, et la durée totale de l’effort.

2.3.1.3

Évaluation de la force musculaire

Pour l’évaluation initiale et finale de la force musculaire au niveau des membres supérieurs et inférieurs, nous avons cherché à déterminer la résistance maximale (1 RM) qui est la charge maximale en kilogramme que le patient peut mobiliser en une reprise dans une amplitude complète. Cette mesure a concerné les muscles abaisseurs du moignon de l’épaule, les fléchisseurs du coude, les extenseurs du coude, les muscles fessiers ainsi que les fléchisseurs et les extenseurs du genou. La valeur retenue était la moyenne de trois mesures du côté le plus puissant. La 1RM était réévaluée au début de chaque semaine afin de mieux réajuster l’intensité du renforcement pour chaque groupe musculaire.

2.3.1.4

Évaluation des troubles métaboliques

Tous les patients ont bénéficié au début et à la fin du protocole des dosages de la glycémie sanguine à jeun, du cholestérol total, des triglycérides, et de la fraction HDL cholestérol.

Nous avons calculé le LDL cholestérol selon la formule de Freidwald Fredrickson .

2.3.1.5

Évaluation de la dyspnée au cours des activités de la vie quotidienne

L’intensité de la dyspnée au cours des activités de la vie quotidienne était appréciée au début et à la fin du protocole par l’échelle visuelle analogique de la dyspnée (EVA dyspnée) cotée de 0 à 100 mm au millimètre prés où 0 représente l’absence de dyspnée et 100 représente la dyspnée maximale imaginable.

2.3.1.6

Évaluation du retentissement psychologique

Au cours de notre étude, nous avons évalué l’état psychologique en utilisant le questionnaire Human Anxiety and Depression scale (HAD) . Cette échelle comporte deux colonnes : une colonne A pour évaluer l’anxiété et une colonne D pour évaluer la dépression. Le maximum de point obtenu pour chaque colonne est de 21 points. Pour un score total entre 8 et 10, il s’agit d’un état anxieux ou dépressif douteux, au-delà de 10 l’état anxieux ou dépressif était certain.

2.3.1.7

Évaluation de la qualité de vie

La qualité de vie a été évaluée par l’ impact of weight on quality of life lite (IWQOL lite) . Cet autoquestionnaire a été traduite en Arabe.

La traduction suivie de l’adaptation de certains items a permis d’obtenir une échelle comportant cinq domaines : la fonction physique, l’estime de soi, la vie sexuelle, la vie sociale et relationnelle et la vie professionnelle.

Le score de chaque item est ensuite rapporté en pourcentage du maximum de score possible, ce qui fait que le score varie entre 0–100. Un score inférieur à 80 % indique que la qualité de vie est altérée, plus le score diminue plus la qualité de vie est altérée.

2.3.2

Les moyens de prise en charge

2.3.2.1

La prescription diététique

L’enquête alimentaire a été réalisée par l’équipe de diététiciennes du service d’endocrinologie du CHU Hédi Chaker Sfax et a intéressé tous nos patients et a eu pour objectifs de préciser : les habitudes alimentaires antérieures, les éventuelles anomalies du comportement alimentaire et de réaliser l’enquête diététique basée sur la technique de l’enquête par interview. Le recueil des données a été réalisé à travers l’utilisation d’un carnet alimentaire (semainier : rapport de 7 jours) et l’utilisation d’un logiciel informatique « BILNUT » version 1991.

Une réduction de 25 à 30 % du niveau calorique antérieur était appliquée chez la plupart de nos patients. Ce régime hypocalorique prescrit était équilibré avec en moyenne 15 % de protéines, 30 à 35 % de lipides, 50–55 % de glucides. Nous avons veillé à ce que les apports alimentaires soient répartis en trois repas avec nécessité d’un petit déjeuner substantiel.

Les trois groupes ont eu un suivi diététique identique avec une consultation initiale, un contrôle au milieu du protocole et un autre lors des dernières séances par une diététicienne du service d’endocrinologie ignorant complètement la nature du protocole suivi.

2.3.2.2

Le réentraînement à l’effort

Tous nos patients ont été conseillés de commencer le régime et de perdre quelques kilos de poids (2–3 kg) avant de débuter les séances de réentraînement à l’effort.

2.3.2.2.1

Entraînement de type aérobie sur tapis roulant

Il s’agit d’un entraînement de type aérobie sur tapis roulant (type Tmo ® MEDICAL). L’intensité de l’entraînement a été fixée à 60 % de la FC max atteinte lors de l’EE de référence effectuée sur tapis roulant selon le protocole de Bruce modifié.

En plus, au fil de l’entraînement, la fréquence cardiaque d’entraînement (FCC) ne correspondait plus toujours au même niveau de charge. Cela s’explique par une amélioration due à l’entraînement, et c’est pourquoi la vitesse en Km/h a été augmentée au fil des séances, tout en gardant la même intensité fixée à 60 % de la FC maximale.

Après une phase initiale d’échauffement réalisée sur tapis roulant pendant cinq minutes à une faible charge, l’entraînement en endurance dure 30 minutes par séance. Il est complété par une phase de récupération et de relaxation de cinq minutes.

Nous avons réalisé trois séances hebdomadaires pour tous les patients avec un nombre total de 24 séances sur une période de deux mois. La surveillance des paramètres cardiovasculaires était assurée par l’infirmière de la salle notant à chaque séance la tension artérielle, la fréquence cardiaque au repos toutes les cinq minutes. Ces données recueillies à chaque séance sont notées dans un carnet de surveillance.

2.3.2.2.2

Le réentraînement de type renforcement musculaire périphérique

Outre un entraînement sur tapis roulant, des exercices de renforcement musculaire périphérique ont été réalisés chez le troisième groupe de patients (G3). Ce sont des exercices de type dynamiques qui ont intéressé aussi bien les membres supérieurs que les membres inférieurs et la paroi abdominale couplée au travail de la respiration.

Au niveau des membres supérieurs, les exercices de renforcement musculaire ont intéressé les muscles abaisseurs de l’épaule, les extenseurs du coude et les fléchisseurs du coude.

Le renforcement était effectué globalement à 60 % de la force maximale volontaire (FMV), réévalué au début de chaque semaine pour ajuster l’intensité. Pour chaque groupe musculaire, le patient réalise trois séries de 20 répétitions chacune entrecoupée d’une pause d’une minute.

Au niveau des membres inférieurs, les exercices de renforcement musculaire se sont déroulés avec les mêmes modalités et ont intéressé le muscle grand fessier, le moyen fessier, les extenseurs et les fléchisseurs des deux genoux.

2.3.2.2.3

Suivi d’une activité physique complémentaire au cours de la semaine

Au cours de notre prise en charge, nous avons encouragé une activité de marche complémentaire. C’est une marche continue pendant 40 à 60 minutes à raison de trois fois par semaine et nous avons vérifié sa bonne observance au début de chaque séance en interrogeant nos patients sur le temps passé en marchant ainsi que sur la distance parcourue.

L’observance de l’activité physique complémentaire a été jugée excellente pour les patients ayant réalisé une activité de marche continue pendant 40–60 minutes à raison de trois fois par semaine, bonne pour les patients ayant réalisé une activité de marche continue pendant 40–60 minutes à raison de deux fois par semaine, moyenne pour les patients ayant réalisé une activité de marche continue pendant 40–60 minutes à raison d’une fois par semaine et mauvaise pour les patients qui ont réalisé une activité de marche insuffisante en durée et en qualité.

2.4

Étude statistique

Nous avons utilisé principalement le test de Khi 2 , l’Anova ou l’analyse des variances, la régression et le test de comparaison des moyennes pour échantillons appariés.

Il convient en plus de préciser que le logiciel SPSS ® 13 est celui retenu pour la codification des fiches de données recueillies ainsi que la réalisation des différents tests cités.

Le test de Khi 2 est employé pour l’étude de la relation entre des variables binaires. Une relation significative existe si la valeur de la statistique Khi 2 de Pearson obtenue est inférieure à 0,05.

Ensuite, l’Anova à un facteur, permet d’effectuer une analyse de variance univarieé sur une variable quantitative dépendante par une variable critère simple (indépendant). Il permet alors de tester l’hypothèse d’égalité des moyennes.

Enfin, la procédure du test T pour échantillons appariés a été utilisée pour étudier l’évolution des chiffres des différents paramètres cliniques et biologiques des patients avant et après prise en charge.

2.5

Résultats

Tous nos patients ont réussi à perdre entre 2 et 3 kg avant d’entamer le protocole.

Cette perte était de l’ordre de 2,45 dans le G1, de 2,50 dans le G2 et de 2,45 dans le G3 ( p = NS).

2.5.1

Caractéristiques épidémiologiques et évaluation du retentissement de l’obésité

L’âge moyen de nos patients était de 37,2 ± 10 ans avec des extrêmes allant de 18 à 60 ans. Notre population était formée de 13 hommes (15,6 %) et de 70 femmes (84,4 %). L’obésité évoluait en moyenne depuis 9,5 ± 6 ans avec des extrêmes allant de trois à 20 ans. Le poids moyen de notre population était de 99,7 ± 17,5 kg avec des extrêmes allant de 76 à 148 kg. L’IMC moyen était de 37,2 ± 5,2 kg/m 2 avec des extrêmes allant de 30 à 53,8 kg/m 2 . La masse grasse chez nos patients était en moyenne de 41,95 ± 7,7 kg soit 41 %, la masse maigre était de l’ordre de 53,5 ± 7,5 kg et le métabolisme de base était de 1742,62 ± 203 Kcal/j. Notre population a comporté 23 patients hypertendus, 12 patients ayant une dyslipidémie et 17 patients diabétiques.

Le Tableau 1 résume les différentes données épidémiologiques et anthropométriques de notre population et leur comparabilité entre les différents groupes.