Abstract

Introduction

Studies of long-term outcome of the shaken baby syndrome (SBS) are scarce, but they usually indicate poor outcome.

Objectives

To describe long-term outcome of a child having sustained a SBS, to ascertain possible delayed sequelae and to discuss medicolegal issues.

Methods

We report a single case study of a child having sustained a SBS, illustrating the initial clinical features, the neurological, cognitive and behavioural outcomes as well as her social integration.

Results

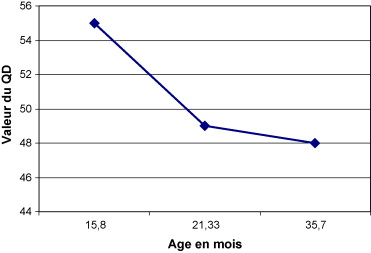

The child sustained diffuse brain injuries, responsible for spastic right hemiplegia leading to secondary orthopaedic consequences, as well as severe cognitive impairment, worsening over time: the developmental quotient measured at 15 months of age was 55 and worsened as age increased. At 6 years and 8 months, the child’s IQ had fallen to 40. Behavioural disorders became apparent only after several months and precluded any social integration. The child eventually had to be placed in a specialised education centre at age 5.

Discussion and conclusion

The SBS has a very poor outcome and major long-standing sequelae are frequent. Cognitive or behavioural sequelae can become apparent only after a long sign-free interval, due to increasing demands placed on the child during development. This case report confirms severity of early brain lesions and necessity for an extended follow-up by a multi-disciplinary team. From a medicolegal point of view, signaling the child to legal authorities allows protection of the child, but also conditions later compensation if sequelae compromise autonomy.

Résumé

Introduction

Les études rapportant un suivi à long terme après syndrome du bébé secoué (SBS) sont rares mais suggèrent toutes un pronostic sombre.

Objectif

Décrire l’évolution clinique à long terme d’une enfant victime d’un SBS, afin d’objectiver la gravité et l’apparition progressive des séquelles et de discuter les implications médicolégales.

Méthode

Nous rapportons un cas unique illustrant le tableau clinique initial d’une enfant victime d’un SBS, son évolution neurologique, cognitive, comportementale et son insertion sociale.

Résultats

L’enfant présentait des lésions cérébrales diffuses, responsables d’une hémiplégie spastique compliquée de troubles neuro-orthopédiques secondaires et d’un retard sévère du développement psychomoteur, se majorant avec le temps : le quotient de développement évalué à 55 à l’âge de 15 mois s’aggravait avec l’âge. Enfin, à l’âge de six ans et huit mois, le quotient intellectuel avait chuté à 40. Des troubles du comportement d’apparition retardée et d’aggravation progressive ont entravé toute tentative d’insertion, l’enfant étant finalement intégrée dans un établissement médicoéducatif à l’âge de cinq ans.

Discussion et conclusion

Le SBS peut laisser des séquelles majeures et définitives, d’installation parfois très différée, par altération des capacités d’apprentissage, devenant plus évidentes lorsque les exigences environnementales envers l’enfant augmentent. Cette observation confirme la gravité des conséquences de lésions cérébrales précoces et la nécessité d’un suivi très prolongé par une équipe multidisciplinaire. Au plan médicolégal, le signalement judiciaire initial permet, outre la protection de l’enfant, la reconnaissance de l’infraction pénale par une expertise judiciaire, conditionnant ainsi une indemnisation ultérieure en cas de séquelles.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Non-accidental head injury is the most frequent cause of mortality and morbidity in neonates . In its minimal form, shaken baby syndrome (SBS) consists of subdural haematoma:

- •

in the absence of any concurrent, accidental injury reported by the baby’s parents or legal guardians;

- •

following a minor accident which is incompatible with the extent of the damage.

In 75 to 90% of cases, the subdural hematoma is associated with uni- or bilateral retinal haemorrhage . SBS is the most severe example of non-accidental head injury trauma and was only described relatively recently: in 1860, Tardieu described a series of 32 cases of battered children, including 18 with pericerebral bleeding at autopsy . In the United States in 1940, Caffey noticed the association between long bone fractures and subdural haematoma in the absence of external signs of maltreatment and (in 1972) coined the name “whiplash shaken baby syndrome”, which unambiguously identified shaking as the causal mechanism. Caffey’s definition of SBS encompassed a set of symptoms, including the presence of a subdural haematoma or sub-arachnoid haemorrhage and retinal haemorrhage which contrasts with the absence of external signs of head injury or the presence of only minor signs . At the same time, Guthkelch reported observations of babies in England having suffered subdural haematoma through shaking . This syndrome can occur in any sociocultural milieu and mainly affects children under the age of 12 months (and under 6 months in particular). Boys are consistently more involved than girls (with a typical gender ratio of 2:1), despite the lack of any real explanation for this phenomenon. Although SBS is not infrequent (with a reported incidence of 24 to 30 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year in the United States and in Scotland ), it is not always diagnosed, and this is true even of the most severe forms . In France, the incidence of SBS (180 to 200 diagnosed cases per year) is certainly underestimated . SBS can lead to death or permanent handicap . The prognosis for shaken babies is not well characterized and there are few studies on the outcomes (and especially the long-term outcomes) in these children. Moreover, the few published studies have used very different recruitment modes and methodologies. Nevertheless, all cite a poor vital, neurological and cognitive prognosis. Hence, the reported mortality varies between 15 and 38% , with a median at 20 to 25% . In terms of neurological and cognitive sequelae, one can observe severe psychomotor development delays, spastic quadriplegia, severe motor disorders, epilepsy, cortical blindness, microcephalus and severe cortical and subcortical atrophy . A recent literature review on the prognosis for non-accidental head injury covered 489 cases; it indicated a mortality rate of 21.6% and a morbidity rate in the survivors that varied from 59 to 100% (depending on the series’ recruitment mode) and averaged 74%. This means that only a quarter of the children were free of sequelae. The prognosis for SBS is significantly correlated with the initial Glasgow score, the presence of major retinal haemorrhage, the presence of a cranial fracture and the extent of the parenchymatous lesions identified in the first 3 months .

Over the years, many SBS victims have been hospitalized in our Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation service, which specializes in acquired brain damage in the child. The huge majority of cases are referred to us by Necker Children’s Hospital, which has been the Paris Île-de-France region’s main hospital for referral of children with severe head injuries since 1994 .

We published an initial, retrospective study on 28 SBS victims subsequently hospitalized in our service between 1995 and 1999 . All these children have since been followed prospectively. The extent of the neurological damage became apparent very early on, after a median follow-up period of 18 months (range: 6 to 43 months) in children with a median age of 2 (range: 1 to 4 years). Brain atrophy was evidenced by a change in the head circumference curve. A break-point in the curve was seen in all children, with an average loss of 2.2 standard deviations (S.D.) for the group as a whole. The average change was 0.5 S.D. for those who seemed otherwise unaffected and 4.4 S.D. for the most severe cases, with one extreme value of 8 S.D. – meaning that brain growth stopped completely in this child. We identified convulsive status as a major prognosis factor.

Here, we report in detail on the case of a female patient with 6 years of follow-up, in order to illustrate the long-term impact of SBS on a child’s development and the resulting legal consequences. We hope that this clinical case history will enable students, therapists and experts in post-trauma rehabilitation to better understand:

- •

SBS itself;

- •

the importance of a diagnosis of shaking;

- •

their role in the legal process.

1.2

Clinical case report

The one-year-old female child “BS” had been born at term and was developing normally (i.e. she was starting to walk and to say a few words). She did not have any siblings. She was found unconscious by the child minder who had been looking after her during the day for the previous 3 weeks. The emergency medical team noted coma (with a Glasgow score of 3) and left mydriasis on arrival. An initial computed tomography (CT) brain scan showed extensive left frontal and temporoparietal subdural haematoma with major hemispherical oedema (the left lateral ventricle was no longer visible) and right deviation of the median line. The haematoma was removed surgically. The bleeding had come from a coronal vein that had become detached from the superior sagittal sinus. Examination of the fundus evidenced bilateral (but predominantly left-side) retrohyaloid and intraretinal haemorrhage having occurred at different times. The coma lasted for 7 days. The intracranial pressure rose to 25 mmHg. There were no convulsions. A subsequent CT scan evidenced extended left hemisphere ischemia and also right frontal internal ischemia. The child had started babbling again 2 days prior to admission to our rehabilitation service (at D20). The head circumference measurement was 46 cm (i.e. within the norm). The child presented major axial hypotonia and had lost the ability to hold her head up or remain in the sitting position. She also presented complete right hemiplegia and a permanent leftward deviation of the head and eyes. She did not react to right-side visual or auditory stimuli and was on phenobarbital.

The following months were marked by altered learning capacities and absences accompanied by major abnormalities on the electroencephalogram (EEG), in the form of uninterrupted bursts of spikes and spike-waves in the left temporal region and spreading to the whole hemisphere. This observation prompted the initiation of vigabatrin treatment at the age of 18 months, followed by replacement with valproic acid at 3 and a half. At the age of 4, the nature of BS’ crises changed since they sometimes led to a fall and were accompanied by ocular revulsion. Nevertheless, the crises were controlled by antiepileptic monotherapy. A routine brain scan at the age of 2 evidenced left hemisphere atrophy.

The head circumference curve showed a breakpoint, with an average shortfall of around –2 S.D. at the age of 6 years and 7 months: the head circumference had been 47.5 cm at the age of 3 (–1 S.D.) and had reached a plateau at 48 cm at the age of 4.

1.2.1

At the age of 3

The child was described as uncooperative and extremely agitated. She could not maintain her attention on a task for more than 30 seconds. She refused most of the games suggested to her, did not understand the instructions and threw the objects on the floor or banged them together or on the table. There was very significant utilization behaviour and an absence of spontaneous, constructive activity: BS liked to move around freely and indiscriminately grabbed anything within her reach (shoes, toys, furnishings, etc.), put them in her mouth and bit them, which required permanent surveillance. She was easily frustrated, screamed for, sometimes, long periods of time and threw objects. Her behaviour made the rehabilitation sessions difficult. She enjoyed contact with adults and often asked for a hug, which had a calming effect. In contrast, she had adversarial relationships with other children: she destroyed whatever they had built, intruded into their games and pulled objects out of their hands. She performed a number of aggressive gestures, such as hitting and biting. The severity of her behavioural disorders (irascibility, language replaced by strident and incessant screams, etc.), worsening attention disorders, agitation and night- and day-time sleep disorders) prompted the initiation of levomepromazine treatment. On the cognitive level, language was neither fluent nor informative, since it was limited to a few words (such as “again”, “dada” and “mama”) with phonological deformations. To convey the fact that she wanted an object, BS spontaneously pointed her finger at it while saying “that” or a word related to the desired activity . The understanding of simple commands was very variable, even in context: BS could indicate some parts of her body but the naming of objects or images was impossible. In Brunet–Lézine’s psychomotor development test, BS accomplished all of the 10-month items but none of the 30-month items. The development quotient (DQ) was 48.

On the neuromotor level, there was persistent right spastic hemiplegia mainly affecting the arm, which was not used – not even for support. The child was not toilet-trained.

In functional terms, BS could walk two or three steps on her own. She was dependent for all activities of daily living. She was capable of starting to eat unassisted but, after a few mouthfuls, stopped and threw her plate onto the floor. At home, she would often wake up during the night and would have trouble going back to sleep. The child was not able to attend school – not even part-time at the hospital’s special unit. The results of successive Brunet–Lézine tests evidenced a progressive developmental shortfall in the child’s abilities ( Figs. 1 and 2 ).

1.2.2

At the age of 6 years and 8 months

Treatment with valproic acid and levomepromazine was ongoing. In behavioural terms, BS was calmer but still had sudden and violent gestures. She was not spontaneously interested by any type of activity and remained extremely slow, easily distracted and easily tired. Stereotypy and utilization behaviour were noted. The child continued to put objects into her mouth indiscriminately. Her degree of agitation required continuous surveillance and made impossible to perform a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan other than under general anaesthesia.

In cognitive terms, the child’s performance level was below that of a 3-year-old, especially regarding orientation: BS could not say whether she was a girl or a boy and did not know how old she was. She could not explain where her home was situated and was unable to tell what point in the day it was. She did not distinguish right from left. Her language was very limited and consisted solely in associating up to three (many unintelligible) words. There were major comprehension disorders. She could obey a few isolated, simple commands but could not follow two simultaneous, simple instructions. She was not able to indicate cubes according to their colour, although she was able to sort them by colour. She could not count objects beyond two. BS could only copy horizontal lines and produce a few doodles. She could not complete a simple jigsaw puzzle and could only fit a few basic shapes together by trial and error. She was not able to imitate the construction of three cubes (a 3-year-old level activity). In the teddy bear cancellation test , BS made eight omissions out of 15, instead of the single omission usually expected at the age of 6. Her memory could not be tested.

In BS’s first attempt at the the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence test (WPPSI-III) , she scored the lowest possible score of 1 for all items. The overall intelligence quotient (IQ) was 40, the verbal IQ was 44 and the performance IQ was 45.

On the neuromotor level, the motor symptoms had not changed but right dorsal scoliosis had appeared. In functional terms, BS was able to walk unaided but standing on one foot, jumping, crouching and running remained impossible. She was not independent with regard to even the simplest activities of daily living. She could only eat with a spoon. In the toilet, she had to be undressed, wiped and dressed again. Outdoors, it was necessary to hold her hand constantly and in shops, she had to be restrained by being placed in the shopping trolley.

1.2.3

Future care

In terms of future care, successive attempts to refer her to a nursery (even a specialist one) and then a primary school ended in failure (despite the best efforts and diligence of the host organisations), in view of BS’s behavioural disorders. The child was also refused by several care homes before finally being admitted (at the age of five) to a highly specialized educational unit.

1.2.4

Legal aspects

T he Neurosurgery Department had filed a legal report for SBS in view of the observed subdural haematoma and retinal haemorrhages having occurred at different time points. Following the initiation of proceedings by the public prosecutor, the examining magistrate charged the suspected perpetrator with “voluntary violence to an under-16 by a person holding authority and having led to total, temporary infirmity for more than a week”. The parents filed as plaintiffs claiming damages and applied to France’s Crime Victim Compensation Commission. The expert medical-legal opinion (given when the child was 2 years old) confirmed that “all the lesions were related to violent shaking, such as that performed in SBS, and no cause other than violent injury could be envisaged”. In the absence of prior anomalies, the development impairments were considered as being directly and unquestionably ascribable to the brain damage. Prior to legal consolidation (in France, the point after which no additional medical treatment can be deemed to improve the handicap and thus at which the state of incapacity is judged to be permanent; in children with severe head injuries, this does not occur before the age of 20), the courts granted compensation for loss of earnings after the mother had given up her job to look after BS and for covering the expenses resulting from the brain damage. The compensation also helped pay for several hours per day of third-party care.

1.3

Discussion

Here, we have provided a detailed description of the long-term clinical outcome of an SBS victim, confirming the severity of the prognosis and in line with the sequelae typically reported in the few available long-term studies .

1.3.1

In neurological terms

In neurological terms and in addition to persistent, invalidating, right side spastic hemiplegia (complicated by the subsequent appearance of scoliosis), BS continues to suffer from relatively severe epilepsy. In SBS, a motor deficit such as hemiplegia or quadriplegia appears to be both persistent and frequent (in 60% of cases in the series reported by Barlow et al. ). Epilepsy appears to be much more common after SBS than after accidental head injury and is often severe and drug-resistant .

1.3.2

Major behavioural disorders

The SBS victim presented major behavioural disorders, which constituted the prime factor in the child’s failure to be admitted to specialist care units. These behaviour disorders also constitute a major aspect of the sequelae found in the literature and were noted in 52% of cases by Barlow et al. . The latter researchers also reported on the high frequency of sleep disorders (24%), which often have a major impact on a family’s quality of life. Prasad et al. and Damasio have suggested that orbitofrontal brain damage early in life perturbs behavioural regulatory mechanisms in general and impairs initiative and adaptation to a social context (with difficulty learning social rules) in particular. In our first study and despite the patients’ young age, behaviour disorders in daily life were already being reported by a quarter of the parents.

1.3.3

With regard to the onset of the sequelae

Some of BS’s disorders only became severe and invalidating after a certain length of time. For example, the behavioural disorders started to cause major problems from the age of 3 onwards. This underlines the importance of the sequelae’s time to onset. Two studies have focused on this aspect of the condition. In 1995, Bonnier et al. reported on outcomes in 13 children with a 7-year follow-up (range: 5 to 13 years). A critical notion in this study was the variable time delay in expression of the symptoms: brain growth arrest after 4 months, epilepsy after 2 years and behavioural disorders appearing and causing problems only 3 to 6 years after the trauma. Only one child was still considered as being sequelae-free after 7 years of monitoring. To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to emphasize the potential mid- and long-term appearance of more subtle disorders than those immediately seen in the shaken babies. Secondly, Barlow et al. studied outcomes in a series of 25 SBS victim. The initial population consisted of 55 children (six of whom died). With a mean monitoring period of 5 years and with almost half the subjects lost to follow-up, 68% of the survivors presented very diverse sequelae. Thirty-six percent had a severe disorder and were totally dependent. Motor deficits were found in 60% of cases, with visual disorders in 48% of cases, epilepsy in 20% of cases, language disorders in 64% of cases and behavioural disorders in 52% of cases.

Overall, as illustrated by our case report, the few long-term SBS follow-up studies generally describe a poor long-term prognosis in 30% of the apparently unaffected children, given that this figure falls over time due to learning problems and the appearance of more demanding environmental requirements, notably at the usual age of school entry. This unfavourable prognosis contrasts with what is still too often erroneously presented as the “Kennard Principle” . This principle was established following work in 1936 by Margaret Kennard who, in order to study motricity in the monkey, created lesions in the motor and pre-motor areas in animals of different ages. She noted that young monkeys recovered more fully and more rapidly than adult monkeys. Subsequently, other authors have extrapolated from the monkey to humans and from pre-motor lesions to all types of lesions – giving rise to a “Kennard Principle” that was not at all formulated by Margaret Kennard! Independently of the experimental work, many rigorous, prospective, controlled studies have since shown in a reproducible manner that this “Kennard Principle” does not hold in cases of widespread lesions (particularly those with frontal predominance and particularly in the young child). In fact, the cognitive sequelae are more severe in the child than in the adult, since the damage affects vulnerable, rapidly developing functions and thus learning abilities. Moreover, the earlier the damage occurs, the more severe the sequelae, since age is one of the major prognostic factors in head injury in the child .

Nevertheless, these false beliefs remain well anchored in the minds of physicians and lawyers: in 1996, Webb et al. set out to study the impact of the “Kennard Principle” on physicians and paramedical professionals. He asked them to comment on the extent of recovery in four fictitious case studies of brain-damaged adults and children in which only the patient’s age differed. In all cases and regardless of their medical speciality or the time since their medical training, the medical professionals predicted a better prognosis when the patient was under 10. Webb et al. concluded that the “Kennard Principle” was still strongly anchored in people’s minds. Likewise, in 2003, Johnson et al. questioned magistrates on the value of expert medical-legal opinions expertises according to whether or not they announced a better prognosis in the child. He found the same result; all the magistrates wrongly thought that brain damage suffered earlier in life had a better prognosis. It is thus important to remain cautious when announcing a prognosis following brain damage in the child – above all when the damage is widespread, as in SBS. In addition to the immediately apparent problems, subtle but nevertheless damaging disorders (such as attention, concentration and memory disorders) may subsequently appear. Moreover, these disorders are exacerbated by the growing demands placed on the child as he/she grows up. It is not possible to predict the outcome with certainty. Extremely long follow-up by a multidisciplinary team is essential and must enable care provision to change as function of the child’s altering condition. The child’s learning ability (and notably cognitive status) must be assessed on a regular basis, in order to determine the time course of these changes.

1.3.4

Better knowledge of the severity of the prognosis in SBS should help reinforce preventive measures

This can be very effective when they are performed systematically with parents in the maternity ward immediately after the child’s birth . Understanding the harmful effect of shaking helps the adult to avoid committing the act and to find a solution other than shaking to stop the baby from crying. Furthermore, reducing the consequences of shaking involves very proactive therapeutic management in the intensive care unit. Lastly, it is important to prevent recurrence. Indeed, one key point is to have diagnosed SBS at the outset . This diagnosis can be broken down into four steps :observation of the existence of intracranial lesions, which must be considered even when confronted with symptoms that are not specific for neurological damage, such as vomiting;a diagnosis of shaking;determination of the shaking’s context;identification of the perpetrator.

The physician is solely responsible for the first two steps. A diagnosis of shaking is necessary and sufficient for a diagnosis of SBS and must involve the application of a rigorous approach. If shaking cannot be unambiguously diagnosed, a diagnosis of SBS must not be made.

Lastly, in order to protect the child and aid the adult, the diagnosis must be reported . In France, the confidentiality of the physician–patient relationship no longer holds in cases of abuse and cruelty to under-16s. In such an event, France’s code of professional medical conduct obliges the physician “to notify the legal, medical or administrative authorities” (which do not include the local protection maternelle et infantile midwifery and social services) “except under particular circumstances which he/she shall judge in all conscience”. What, then, might justify not reporting such an incident? The eventuality that the exasperated adult only shook the child once, perhaps? But would the physician have the adopted same attitude with an adult or elderly victim? Fear of an overly severe response from the police or judicial system? But is this risk serious enough to prevent reporting? Fear that the adult might be imprisoned? In fact, the penal response to such an incident features a wide range of potential solutions other than imprisonment, including the obligation to seek medical or psychiatric treatment. Fear of worsening the relationship with the family or those within the family? But surely shaking is more harmful for a family than a report of shaking?

1.3.5

Notifying an incident to the legal authorities also enables initiation of the compensation process

This is fundamental in the event of subsequent sequelae (which are impossible to accurately forecast in the initial phase). In France, whatever the context and the perpetrator, shaking constitutes an offence (i.e. a voluntarily or involuntarily harmful act committed by a third person) and the victim becomes eligible for compensation. This can be obtained as damages before a penal or civil court or by petitioning the Crime Victim Compensation Commission until up to 3 years after the victim comes of age (i.e. at the age of 21, in France), even if the perpetrator has not been identified. Nevertheless, a causal relationship with the offense constituted by the shaking must have been confirmed in a medical-legal appraisal. The lack of acknowledgement of the offense deprives the child of the right to any subsequent compensation – compensation that is a major factor in reducing handicap because it enables the payment of ongoing costs, such as medical care that is not reimbursed by the health insurance system (occupational therapy, psychomotricity, etc.) or the cost of third-party care. This attention must be provided as soon as the child’s need for care becomes related to its brain damage rather than its age and must not be skimped on when the parents themselves assume this role.

At the time of legal consolidation of the injuries (i.e. not before the age of 20, in France ), this procedure also enables payment of costs in adult life and particularly third-party care if the individual is not independent.

If one of the parents is potentially the perpetrator of the shaking, this situation may lead to conflict between the child’s interests and those of the parent(s); it is then necessary to request the designation of a legal professional as an ad hoc administrator for defending the child.

In conclusion, this detailed clinical case report illustrates the immediate and delayed consequences of shaking-induced brain damage in a shaken baby and underlines the importance of long-term follow-up. It also illustrates the value of diagnosing and reporting the shaking in order to protect the child and maintain its rights in general and its right to compensation in particular.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Chez le nourrisson, la violence à enfant est la cause la plus fréquente de mortalité et morbidité par traumatisme crânien . Le syndrome du bébé secoué (SBS) comporte, dans sa forme minimale, un hématome sous-dural chez un nourrisson sans notion de traumatisme rapporté par les adultes référents (ou un traumatisme minime, incompatible avec l’importance des lésions). Il s’associe dans 75 à 90 % des cas à des hémorragies rétiniennes uni- ou bilatérales . Le SBS est la manifestation la plus sévère des traumatismes crâniens non accidentels. Sa description est relativement récente : en 1860, Tardieu décrivit une série de 32 cas d’enfants battus, dont 18 avec saignements péricérébraux à l’autopsie . Aux États-Unis, en 1940, Caffey remarqua l’association de fractures osseuses des os longs et d’hématomes sous-duraux sans signes extérieurs de maltraitance et retint en 1972 l’appellation « whiplash shaken baby syndrome », rendant compte du secouement comme mécanisme causal. Il regroupa dans ce syndrome un ensemble de symptômes comportant la présence d’un hématome sous-dural ou d’hémorragies sous-arachnoïdiennes et d’hémorragies rétiniennes, contrastant avec l’absence ou la pauvreté des signes externes de traumatisme crânien . Au même moment, Guthkelch, en Angleterre, rapporta des observations de bébés avec hématome sous-dural par secouement . Ce syndrome, qui peut survenir dans n’importe quel milieu socioculturel, touche les enfants de moins de un an, particulièrement de moins de six mois et de façon constamment prédominante, sans qu’il y ait de réelle explication, les garçons (sex-ratio de 2/3 généralement). Il est relativement fréquent, mais le diagnostic n’est pas toujours fait, qu’il s’agisse des formes les plus sévères ou des formes les plus légères . L’incidence est de 24 à 30 cas pour 100 000 habitants par an aux États-Unis ou en Écosse . L’incidence estimée du SBS diagnostiqué en France est de 180 à 200 cas par an et elle est certainement sous-estimée . Or le SBS peut entraîner la mort ou être à l’origine de séquelles définitives . Le pronostic du SBS est mal connu car les études sur le devenir de ces enfants sont peu nombreuses, surtout en ce qui concerne le devenir à long terme ; de plus, elles utilisent des modes de recrutement et des méthodologies très variées. Néanmoins, toutes évoquent un pronostic vital, neurologique et cognitif sombre. Ainsi, la mortalité rapportée varie de 15 à 38 % , avec une médiane à 20 à 25 % . En ce qui concerne les séquelles neurologiques et cognitives, on peut observer un retard profond de développement psychomoteur, une quadriplégie spastique, ou des troubles moteurs sévères, une épilepsie, une cécité corticale, une microcéphalie, avec une atrophie cortico-sous-corticale sévère . Une revue récente de la littérature concernant le pronostic du traumatisme crânien non accidentel , et portant sur les 489 cas rapportés dans la littérature, indiquait un taux de mortalité de 21,6 %, et une morbidité chez les survivants variant de 59 à 100 % selon les modes de recrutements des séries de patients, avec une moyenne de 74 %, soit seulement un quart des enfants indemnes de séquelles. Le pronostic est significativement lié au score de Glasgow initial, à la présence d’hémorragies rétiniennes importantes, à la présence d’une fracture du crâne associée et à l’étendue des lésions parenchymateuses mises en évidence dans les trois premiers mois .

De nombreux enfants victimes de SBS ont été hospitalisés dans notre service de médecine physique et réadaptation spécialisé dans l’atteinte cérébrale acquise de l’enfant. La très grande majorité des enfants nous a été adressée par l’hôpital Necker–Enfants Malades, qui accueille depuis 1994 les enfants franciliens après traumatisme crânien grave .

Nous avons rapporté une première étude rétrospective concernant 28 enfants victimes de SBS hospitalisés consécutivement dans notre service entre 1995 et 1999 avec un diagnostic de SBS .

L’ensemble de ces enfants a été suivi. Nous avons constaté très précocement, après un recul médian de 18 mois (variant de six à 43 mois), chez des enfants dont l’âge médian était de deux ans (un à quatre ans), l’importance de l’atteinte neurologique. L’atrophie cérébrale était objectivée par l’évolution de la courbe du périmètre crânien. La cassure de la courbe était constante pour tous avec perte de 2,2 deviations standard (DS) en moyenne pour l’ensemble du groupe. Elle était de 0,5 DS pour ceux qui semblaient indemnes et de 4,4 DS en moyenne pour les cas les plus sévères, avec un extrême à 8 DS ce qui signifiait pour cet enfant une interruption complète de la croissance cérébrale. Nous avions identifié comme facteur pronostique majeur la survenue d’un état de mal initial.

Nous avons choisi de rapporter le cas détaillé d’une patiente avec un recul de six ans, afin d’illustrer, d’une part, l’incidence du SBS à long terme sur le développement de l’enfant et, d’autre part, les conséquences médicolégales qui en découlent. Cette histoire clinique a pour but de permettre aux étudiants, aux thérapeutes (et aux experts en réparation du dommage corporel) de mieux connaître le SBS, l’importance du diagnostic de secouement, mais aussi leur rôle dans le processus médicolégal.

2.2

Présentation du cas clinique

L’enfant « BS », âgée de un an, de sexe féminin, était née à terme et son développement était normal (elle commençait à marcher et à dire quelques mots). Elle était enfant unique. Elle fut retrouvée inconsciente par l’assistante maternelle qui la gardait dans la journée depuis trois semaines. À l’arrivée du SAMU, fut constaté un coma avec un score de coma de Glasgow à 3 et une mydriase gauche. Le scanner cérébral initial montrait un volumineux hématome sous-dural fronto-temporopariétal gauche avec œdème hémisphérique majeur (le ventricule latéral gauche n’était plus visible) et déviation à droite de la ligne médiane. L’hématome fut évacué chirurgicalement. Le saignement provenait d’une veine coronale désinsérée du sinus longitudinal supérieur. Le fond d’œil objectiva des hémorragies rétrohyaloïdiennes et intrarétiniennes bilatérales, d’âges différents, à prédominance gauche. Le coma dura sept jours. La pression intracrânienne s’éleva à 25 mm de mercure. Il n’y a pas eu d’état de mal clinique. Le scanner de contrôle objectiva une ischémie étendue, hémisphérique gauche mais également frontale interne droite. À l’arrivée dans le service de rééducation à j20, l’enfant babillait à nouveau depuis deux jours. Le périmètre crânien était de 46 cm (dans la moyenne). L’enfant présentait une hypotonie axiale majeure, ayant même perdu la tenue de la tête et la station assise. Elle présentait également une hémiplégie droite complète ainsi qu’une déviation permanente de la tête et des yeux vers la gauche Elle ne réagissait pas aux stimuli visuels ni sonores droits. Elle était sous phénobarbital.

L’évolution fut marquée par une altération des capacités d’apprentissages et la survenue dès les premiers mois d’absences avec anomalies majeures à l’électroencéphalogramme (EEG), sous forme de séquences ininterrompues de pointes et pointes ondes en temporal gauche, diffusant à tout l’hémisphère, justifiant la mise sous vigabatrin à l’âge de 18 mois, suivie d’un relais à trois ans et six mois par acide valproïque. À l’âge de quatre ans, les crises de BS se modifièrent et pouvaient entraîner une chute accompagnée d’une révulsion oculaire. Néanmoins, les crises furent contrôlées par une monothérapie. Le scanner cérébral de contrôle à deux ans objectivait une atrophie de l’hémisphère gauche.

La courbe du périmètre crânien objectiva une cassure avec passage de la moyenne à –2 DS à l’âge de six ans et sept mois : le périmètre crânien était passé à 47,5 cm à l’âge de trois ans (–1 DS), puis avait atteint un plateau de 48 cm depuis l’âge de quatre ans.

2.2.1

À l’âge de trois ans

L’enfant était décrite comme peu coopérante, extrêmement agitée. Elle ne pouvait maintenir son attention sur une tâche plus de 30 secondes. Elle refusait la plupart des jeux proposés, ne comprenait pas les consignes, jetait les objets par terre ou les tapait les uns sur les autres ou sur la table. Il existait un comportement d’utilisation très important sans aucune activité construite spontanée : BS aimait se déplacer librement et attrapait sans discernement tout ce qui se trouvait sur son passage (chaussures, jeux, meubles) pour le porter à la bouche et le mordre, ce qui nécessitait une surveillance permanente. Elle était intolérante à la frustration, poussant des cris stridents parfois ininterrompus et jetant les objets autour d’elle. Son comportement rendait les séances de rééducation difficiles. Elle appréciait le contact de l’adulte et réclamait d’être prise dans les bras, ce qui la calmait. En revanche, elle avait des relations conflictuelles avec les autres enfants, car elle détruisait leurs constructions, était intrusive dans leurs jeux et leur arrachait les objets des mains. Elle avait des gestes agressifs comme taper, mordre. L’importance des troubles du comportement (irascibilité, langage remplacé par des cris stridents et incessants, accroissement des troubles attentionnels, de l’agitation, troubles du sommeil nocturne et diurne) avait conduit à instaurer un traitement par levomépromazine. Sur le plan cognitif, le langage était non fluent, non informatif, limité à quelques mots comme « encore, papa, maman », avec des déformations phonologiques. La dénomination d’objets ou d’images était totalement impossible. Pour faire comprendre son désir d’un objet, elle recourrait spontanément au pointage du doigt associé au mot « ça » ou à un mot en lien avec l’activité désirée . La compréhension d’ordres simples était très inconstante, même en contexte : BS pouvait désigner sur elle-même certaines parties du corps mais la désignation d’objets ou d’images était impossible. À l’examen du développement psychomoteur de Brunet–Lézine, tous les items de dix mois étaient réussis et aucun item de 30 mois. Le quotient de développement (QD) était de 48.

Sur le plan neuromoteur, il persistait une hémiplégie droite spastique, prédominant au membre supérieur droit. Le membre supérieur n’était pas utilisé, même comme membre d’appoint. L’enfant n’avait pas acquis la propreté.

Sur le plan fonctionnel, l’enfant pouvait faire deux ou trois pas seule. Elle était dépendante pour toutes les activités de la vie quotidienne. Elle pouvait commencer à manger seule, mais après quelques bouchées, s’arrêtait ou jetait son assiette par terre. Au domicile, il lui arrivait encore souvent de se réveiller la nuit, et se rendormait difficilement. L’enfant n’était pas scolarisable, même à l’école adaptée de l’hôpital à temps très partiel. Les résultats aux passations successives de l’examen du développement psychomoteur de Brunet-Lézine objectivaient le décalage progressif des compétences de l’enfant ( Fig. 1 et 2 ).