Chapter 4 Physical Examination

This chapter will outline the general physical examination and tests that aid in the differential diagnosis of the most common conditions that present in whiplash-injured patients. Succeeding chapters (5 through 8) cover a more detailed examination of specific whiplash-associated disorders. If imaging has been performed prior to the examination, such as in the emergency room, these views should be reviewed prior to beginning the exam. If clinical judgment suggests further imaging or if none has been performed, then it may be prudent for this to be ordered. It should be kept in mind with whiplash patients, as with other traumatic injuries, the symptoms are often worse the second day after the injury. In the case of fractures, these may not be clearly visualized on radiographs until a few days have passed; therefore, further imaging should be ordered and fractures should be ruled out if the patient’s condition has worsened significantly. (See Chapter 5.) If instability is suspected, dynamic imaging should be ordered immediately.

Clinical assessment, including the physical examination, is a continuous process of evaluation, intervention, re-evaluation, and reflection.1 Following the patient’s story (Chapter 3), the subjective and objective examination is carried out. It is crucial in the initial stages of the examination to remember the fragility of the patient who may have suffered both physical and mental trauma. Grieve2 stresses the vulnerability of the whiplash patient to rough handling. He notes that these patients are quite different from those suffering from a single peripheral joint injury.

If the badly injured whiplash patient is handled vigorously with careless movement, the exacerbation can be severe, with headaches of hideous intensity, bizarre visual upset, psychic distress amounting to abject misery, and cervical pain of frightening viciousness.2

Patient-centered practitioners heed this caution.

Listening to the Patient

The patient’s subjective complaints present a pattern that leads to a physical diagnosis. It is important to listen carefully to render a more precise diagnosis. It is not enough to simply use a muscle strain or ligamentous sprain as a diagnosis without identifying the structures involved. The physical diagnosis is formulated from the dysfunction presenting in the muscle injury and pain syndromes (Chapter 6), articular and ligamentous structures (Chapter 8), and the neurological system (Chapter 7). Skill in extracting the appropriate information requires care, patience, and an open mind. Gaining the patient’s confidence is not only reassuring but encourages compliance with future therapeutic recommendations. Patient-centered care recognizes the individual differences in the general population that must be considered in the physical measurement and observation of patients with neck pain.

The Pain Drawing

The pain drawing is a useful first step in formulating a diagnosis and can indicate both physical and psychological problems. Described by Ransford, Cairns, and Mooney as a psychological screen,3 the pain drawing demonstrated better than 80% correlation with the hysteria and hypochondriasis levels of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. The pain drawing is also useful to guide the physical examination. When the pain drawing is consistent with anatomical referral patterns, no points are assessed for psychological disorders. When pain is indicated outside the boundaries of the body, in a nonanatomical pattern, over the entire body, in both the upper and lower extremities, or bilaterally in the absence of physical findings, then psychological assessment is indicated. One point for each abnormal physical pattern is assigned to the pain drawing. With a score higher than 3 points, there is less likelihood of a good outcome from treatment independent of psychological intervention.

It has been demonstrated that patients who are psychologically normal at the time of injury can develop abnormal psychological profiles if symptoms persist for 3 months.4 If pain drawings are filled out each visit, later pain drawings may indicate psychological distress from ongoing pain. It must be kept in mind that patients exhibiting symptoms and signs of fibromyalgia will frequently indicate bilateral pain involving both upper and lower extremities. With careful palpation of the typical sites of exquisite tenderness on minimal pressure, a diagnosis of fibromyalgia can be differentiated. (See Chapter 6.)

The pain drawing can be an extremely useful first step to direct the examination to determine the structures injured. The patient can indicate not only the site of pain, but also different symbols can be used to indicate the type of pain (Figure 4-1). Travell and Simons5 have mapped the referral patterns of trigger points found in muscles, and those with injury to the musculature from whiplash trauma can be readily identified through palpation using the pain diagram as a starting point. (See Chapter 6.)

Chief Complaints and General Assessment

Recording the patient’s chief complaints provides a starting point to guide treatment of the acute patient and suggests, if necessary, a prognosis for long-term management. Table 4-1 outlines the most common symptoms associated with whiplash trauma. Any medications being used should be noted, as heavy pain medication can affect physical findings. The physical examination is a general assessment that precedes focus on the chief complaints. This should include obtaining a blood pressure reading, temperature, heart rate, and vital signs. How the patient moves about, the patient’s gait, and both standing and sitting posture should be observed. There is considerable variation in static posture between individuals, and the challenge is to determine the relevance of a patient’s posture to the presenting signs and symptoms. A more dynamic analysis of posture generally provides more information. It is more useful to observe the patient’s sitting posture to see if adequate mobility is present in the cervical region. If guarding is present, muscular control strategies should be noted. Assessment of shoulder girdle movement is necessary if upper extremity injury is suspected, and occasionally there will be low back and lower extremity problems that must be addressed.

TABLE 4-1 Common Symptoms of Whiplash-Associated Injury

| Symptom | Origin of the Symptom |

|---|---|

| Headache | Suboccipital muscles, zygapophyseal joints, myofascial trigger points, trigeminal nerve complex |

| Neck pain and stiffness | Cervical muscles, zygapophyseal joints, cervical nerve roots, cervical disc |

| Shoulder pain | Shoulder joint, rotator cuff, scapular muscles |

| Arm and hand numbness | Scalene muscles, zygapophyseal joints, cervical nerve roots, brachial plexus |

| Disorientation, irritability | Brain |

| Visual disturbances | Vertebral basilar artery network, brain stem, cervical spinal cord |

| Memory loss and difficulty concentrating | Brain |

| Vertigo | Cervical sympathetic nerves, vertebral artery, inner ear |

| Difficulty swallowing | Pharynx |

| Ringing in the ears | Temporomandibular joint, basilar arteries, cervical sympathetic chain, inner ear |

| Nausea | Vagus nerve |

| Dizziness, light-headedness | Cervical sympathetic nerves, brain, inner ear |

| Poor posture and balance | Paravertebral muscles, disturbed proprioceptors, zygapophyseal joints, cervical nerve roots |

Modified from Evans RC: Illustrated orthopedic physical assessment, 3rd ed, St Louis, 2009 Mosby.

Analysis of Cervical Motion

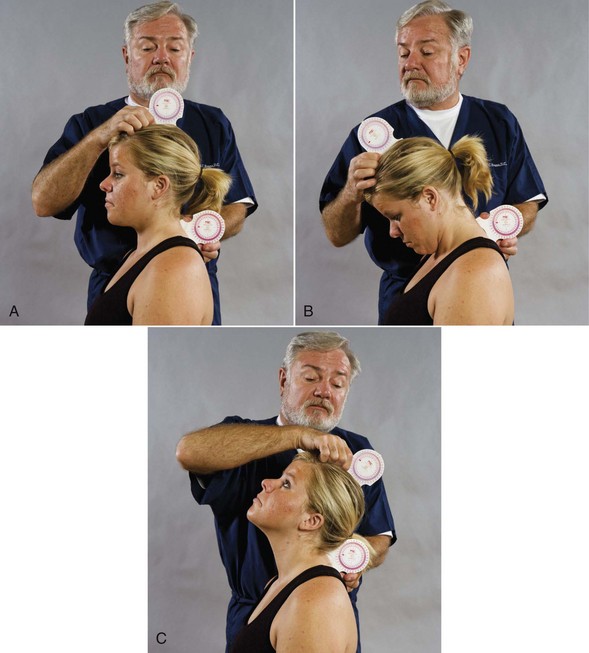

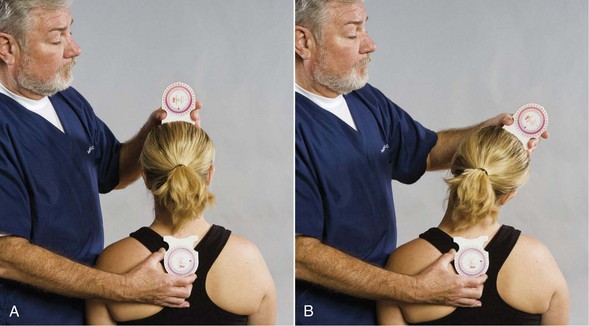

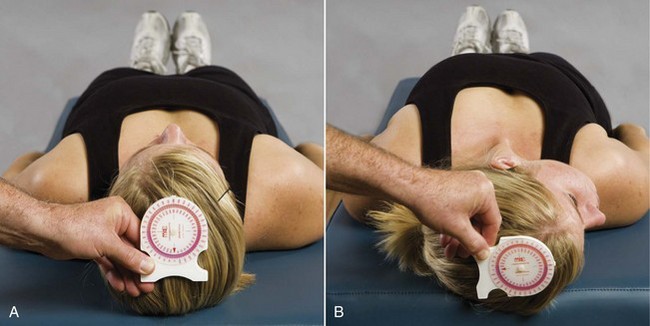

Measurement and assessment of the active range of cervical motion, including pain response, is fundamental to examination of patients who have suffered whiplash trauma. Deficits in cervical range of motion have been shown to differentiate patients with neck disorders from asymptomatic subjects.6–9 The use of an inclinometer provides a quantitative measurement of range of motion (Figures 4-2, 4-3, 4-4). Observation of the patient during range-of-motion testing gives a qualitative measure of the patient’s pain response and pattern of control of movement.

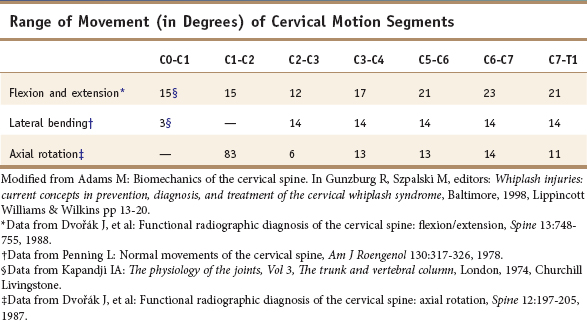

Segmental Cervical Movement

The typical cervical vertebra is wider than it is high, with comparatively large vertebral foramina. Almost 40% of the height of the cervical spine from C2 to C7 is made up of intervertebral discs, so it is not surprising that it is the most mobile region of the spine. Stability is sacrificed, however, with this mobility, making the cervical spine most vulnerable to injury. Each typical motion segment contributes 6 degrees of freedom of motion (Table 4-2). The movement of the C1 around the dens of C2 provides over 80 degrees of rotation. The condyles of the skull provide for slight flexion and extension with even less lateral flexion. (See Table 4-2.) Restriction of segmental motion, although it may contribute only slightly to overall cervical range of motion, can cause significant pain and dysfunction when not treated. (See Chapter 8.)

Assessment of segmental motion through hands-on examination should include static and motion palpation.11 Following assessment of general cervical motion (see Figures 4-2, 4-3, 4-4), segmental symmetry and movement should be palpated. (See Chapter 8.) Tissue tone, texture, and temperature are also palpated.11 This may require referral to a specialist such as a chiropractor if the practitioner is not trained and skilled in this procedure. A pulling away on palpation is an indication of localized tenderness. This may also be verbalized by the patient. Table 4-3 presents standardized grading for muscle strength, tenderness, frequency of spasm strain and sprain, in addition to a modified grading system for whiplash-associated disorders.

TABLE 4-3 Standardized Charting Nomenclature

| Grading Muscle Strength |

| Tenderness Grading Scale |

| Frequency |

| Grading Spasm |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|