Chapter 15 Pharmacological treatments in rheumatic diseases

KEY POINTS

The pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases is diverse and often involves a complex mix of immunological and biomechanical mechanisms.

The pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases is diverse and often involves a complex mix of immunological and biomechanical mechanisms. Prior to prescribing pharmacological therapy, the needs of the patients, alternative non-pharmacological remedies and drug interactions (the pharmaco-dynamics and pharmaco-kinetics) need to be considered.

Prior to prescribing pharmacological therapy, the needs of the patients, alternative non-pharmacological remedies and drug interactions (the pharmaco-dynamics and pharmaco-kinetics) need to be considered. Symptomatic management of pain involves analgesics (e.g. paracetamol, NSAIDs, opioids) and therapy is titrated according to severity of pain with such therapies tailored to individual needs and co-morbidities.

Symptomatic management of pain involves analgesics (e.g. paracetamol, NSAIDs, opioids) and therapy is titrated according to severity of pain with such therapies tailored to individual needs and co-morbidities. For people with osteoarthritis, current therapies are aimed at symptom control. However for people with inflammatory arthritis, treatment of the underlying inflammatory process is required. This will involve anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticosteroids, and disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). There is evidence that DMARDs are able to modulate the disease process in inflammatory arthritis and especially with the newer biologic drugs, prevent progression of joint damage and even induce remission.

For people with osteoarthritis, current therapies are aimed at symptom control. However for people with inflammatory arthritis, treatment of the underlying inflammatory process is required. This will involve anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticosteroids, and disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). There is evidence that DMARDs are able to modulate the disease process in inflammatory arthritis and especially with the newer biologic drugs, prevent progression of joint damage and even induce remission. While increased understanding and knowledge of the pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases has resulted in increased therapeutic options, all pharmacological therapies are associated with adverse events. For optimal outcomes consumer and clinician education are essential, together with a multi-disciplinary approach for complex problems.

While increased understanding and knowledge of the pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases has resulted in increased therapeutic options, all pharmacological therapies are associated with adverse events. For optimal outcomes consumer and clinician education are essential, together with a multi-disciplinary approach for complex problems.PAIN

The word pain comes from Latin ‘poena’ meaning fine or penalty. Pain is a complex phenomenon involving biopsychosocial interactions, and detailed mechanisms are beyond the scope of this chapter. In brief, pain perception peripherally is mediated by the terminal endings of finely myelinated A delta and of non-myelinated C fibres. Chemicals produced locally as a result of injury produce pain by direct stimulation or by sensitizing the nerve endings. A-delta fibres are responsible for the acute pain sensation, which may be followed by a slower onset, more diffuse pain mediated by the slower conducting C fibres. Most sensory input enters the spinal cord via the dorsal spinal roots. When the signal reaches the spinal cord, a signal is immediately sent back along motor nerves to the original site of the pain, triggering the muscles to contract (Kidd et al 2007). The pain signal is also sent to the brain. Only when the brain processes the signal and interprets it as pain do people become conscious of the sensation. Pain receptors and their nerve pathways differ in different parts of the body and the type of pain felt depends on the stimuli. These stimuli may be mechanical, thermal or chemical.

INFLAMMATION

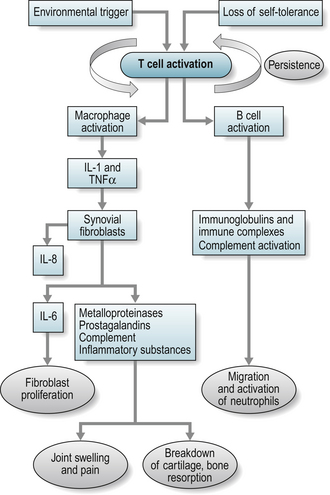

However, the triggering event for inflammation in many inflammatory arthritides is unclear and both environmental and genetic triggers have been considered i.e. exposure to an environmental antigen in a genetically predisposed individual. It is known that a foreign antigen activates T-cells resulting in an inflammatory response. This process is paramount in the body’s normal defence against infection, when the process is controlled and subject to inhibitory mechanisms. Uncontrolled and autonomous, this process can result in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In RA, activated T-cells secrete inflammatory cytokines that lead to chronic activation of B cells and immunoglobulin synthesis (see Fig. 15.1). The pro-inflammatory cytokines include interleukin (IL)-1 and tumour necrosis factor α (TNF) that in turn stimulate the production of more cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8 (Jovanovic et al 1998). The result is pain, chronic synovitis and eventually local tissue and bone destruction.

PRINCIPLES OF CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Before prescribing a therapeutic agent, two main questions must be answered:

DRUGS USED IN RHEUMATIC DISEASES

ANALGESICS

Paracetamol

Paracetamol, also known as acetaminophen in the USA, is one of the most commonly used non-narcotic analgesics; it is also an anti-pyretic agent (lowers temperature). It is recommended as the first line analgesic in OA by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and European League against Rheumatism (EULAR). It is usually taken orally but may be used per rectum. Orally it is well absorbed and peak plasma concentrations are reached in 30–60 minutes. A proportion is bound to plasma proteins and the drug is inactivated in the liver. The plasma half-life of paracetamol is 2–4 hours. It is a weak inhibitor of cyclo-oxygenase (COX-1) (Warner et al 1999) at therapeutic doses.

The usual dose of paracetamol in adults is in the range of 1 gram three or four times daily. The incidence of side effects at therapeutic levels is low so routine monitoring is not required. Toxic doses (two to three times the maximum therapeutic dose) can cause fatal renal and liver failure. This effect is exacerbated by concomitant alcohol ingestion and in patients with active liver disease (Clissold 1986).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree