Percutaneous Fixation of Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

Randall T. Loder

INTRODUCTION

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is defined as a posterior and inferior slip of the proximal femoral epiphysis relative to the metaphysis. However, the relationship between the epiphysis and its articular surface relative to the acetabulum is unchanged; rather the slip is better described as anterior and superior displacement of the proximal femoral metaphysis to the epiphysis. The technique of percutaneous screw fixation is markedly dependent upon an understanding of this concept.

Most (>95%) SCFEs are stable (1), which is defined as the ability to walk, with or without crutches. An unstable SCFE is defined as the inability to walk, with or without crutches. The differentiation between these two types is very important regarding the prognosis for avascular necrosis (AVN). The risk of AVN in a stable SCFE approaches zero. The risk in a child with an unstable SCFE may be up to 50%. The techniques of percutaneous fixation for both types of SCFEs are described in this chapter.

THE STABLE SCFE

A child with a stable SCFE has a history of intermittent limp for several weeks to months. It may or may not be associated with thigh, knee, or groin pain. Hip pain is variably present, often resulting in diagnostic delay (2). Physical examination will show loss of internal rotation and spontaneous external rotation with hip flexion (Drehmann sign) in the more severe SCFE. Abduction and flexion are usually decreased, especially in the severe case. Shortening of the lower extremity with varying degrees of thigh atrophy is noted in the long-standing case. Parents often describe the child’s gait as being progressively outtoed; concomitantly, they note increasing limp due to a slowly progressive limb-length discrepancy and abductor disadvantage due to a decreasing articulotrochanteric distance.

Indication for Percutaneous Fixation of SCFE

Stabilization is needed for any child with a stable SCFE and an open physis; without stabilization, progression nearly always occurs. The goals of treatment are to (a) prevent further slipping until physeal closure; (b) avoid complications, primarily those of AVN and chondrolysis; and (c) maintain adequate hip function. Presently most authors advocate a percutaneous in situ fixation with a single screw for mild or moderate SCFEs. Treatment of the severe SCFE is more controversial; primary osteotomy and/or surgical dislocation with a modified Dunn procedure have been advocated by some in an attempt to improve joint mechanics, improve motion, and prolong hip function

compared to an in situ fixation (3). However, the incidence of complications is higher with osteotomy than in situ fixation. It is safe to say that most surgeons today still recommend in situ fixation as the primary treatment for a severe SCFE. Later secondary procedures addressing femoroacetabular impingement may be necessary, such as osteochondroplasty (either arthroscopic or via open surgical dislocation) and/or proximal femoral realignment osteotomy.

compared to an in situ fixation (3). However, the incidence of complications is higher with osteotomy than in situ fixation. It is safe to say that most surgeons today still recommend in situ fixation as the primary treatment for a severe SCFE. Later secondary procedures addressing femoroacetabular impingement may be necessary, such as osteochondroplasty (either arthroscopic or via open surgical dislocation) and/or proximal femoral realignment osteotomy.

Preoperative Preparation

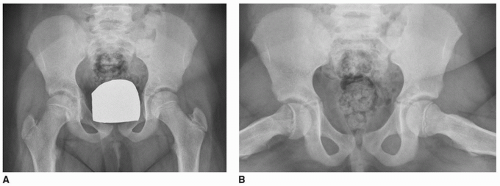

The diagnosis is confirmed with an AP and lateral pelvis radiograph (Fig. 19-1); both views are mandatory as an early SCFE is often seen only on the lateral view. Both hips should always be visualized, as the incidence of simultaneous bilaterally may approach 20%. Either frog lateral or cross-table lateral radiographs may be used. Proponents of the cross-table lateral view argue that the variability with frog positioning due to limitation of hip motion inaccurately represents the SCFE. The frog view can also theoretically convert a stable SCFE to an unstable SCFE. Proponents of the frog lateral view argue that the lateral epiphyseal-shaft angle, a commonly used method to assess slip magnitude, can only be measured on that view. Comparisons between literature series are also possible with this view due to its common use.

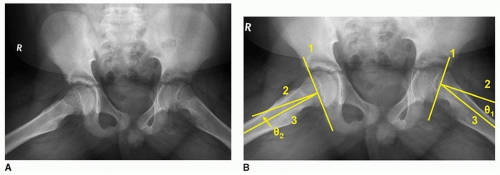

Slip magnitude is frequently measured with the epiphyseal-shaft angle (4) on the frog lateral pelvis radiograph (Fig. 19-2). The first line is drawn between the anterior and posterior tips of the

epiphysis at the physeal level; the second line is perpendicular to this epiphyseal line. A third line is drawn along the mid-axis of the femoral shaft. The epiphyseal-shaft angle is the angle formed by the intersection of lines 2 and 3. It is measured for both hips, and the magnitude of slip displacement is the angle of the involved hip minus the angle of the contralateral normal hip. In the case of bilateral SCFEs, 10 to 12 degrees is used as the normal hip angle. SCFEs are classified as mild (<30 degrees), moderate (30 to 50 degrees), or severe (>50 degrees).

epiphysis at the physeal level; the second line is perpendicular to this epiphyseal line. A third line is drawn along the mid-axis of the femoral shaft. The epiphyseal-shaft angle is the angle formed by the intersection of lines 2 and 3. It is measured for both hips, and the magnitude of slip displacement is the angle of the involved hip minus the angle of the contralateral normal hip. In the case of bilateral SCFEs, 10 to 12 degrees is used as the normal hip angle. SCFEs are classified as mild (<30 degrees), moderate (30 to 50 degrees), or severe (>50 degrees).

In a child with a unilateral SCFE, the question of prophylactic fixation of the opposite hip arises. This is controversial. However, when the patient’s triradiate cartilage is still open, there is a much higher incidence of a contralateral SCFE, and prophylactic fixation should at least be considered (5). In children with atypical SCFEs (associated with an endocrinopathy, renal osteodystrophy), prophylactic fixation should be very strongly considered (Fig. 19-3).

Surgical Procedure

Cannulated screw systems are most commonly used for percutaneous fixation of a stable SCFE (6). Stainless steel screws should nearly always be used, and never titanium. If screw removal is needed later, removal of a titanium screw carries a much higher chance of complications and/or inability to actually successfully remove the screw. Also, fully threaded screws are easier to remove than are partially threaded screws, as the screw track for the threads does not have to be recut during removal. The goal of fixation is to place a single screw into the center of the epiphysis in both AP and lateral planes. Either a fracture table or radiolucent table can be used. I prefer a fracture table, as the blind zone is much less in a true lateral projection compared to a frog lateral projection, which theoretically reduces the risk of inadvertent joint penetration by the screw. However, there has been no demonstrable difference between the two table types.

My technique is to position the patient supine on the fracture table. Care must be taken when transporting the patient onto the fracture table; no reduction is performed, and forceful traction is not applied to the lower extremity. The fracture table is simply a “positioning device,” allowing the involved limb to lie comfortably in its natural position of external rotation. The opposite limb is placed into abduction with the hip extended, and the image intensifier is moved into position between the two lower extremities.

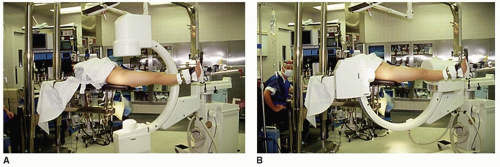

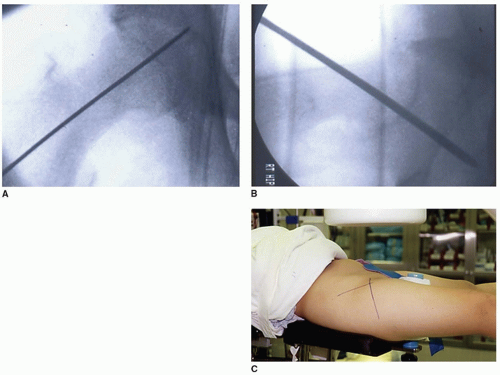

Using a fracture table requires moving the image intensifier rather than the lower extremity during the procedure. An experienced radiographic technician is a must, as well as a high-quality image intensifier that will give satisfactory images that can be difficult in these often very heavy children. (If you are fortunate to have two image intensifiers simultaneously available, biplanar fluoroscopy can be used). Prior to surgical draping, the ability to obtain adequate AP and cross-table lateral images is confirmed (Fig. 19-4). A guide pin is then placed onto the skin overlying the proximal femur and an AP image obtained. The pin is positioned in the center of the epiphysis and perpendicular to the physis (Fig. 19-5A). A line is drawn on the skin to record this guide pin position in the AP projection. A similar skin line is drawn for the lateral image, again positioning the pin so that it is in the center of the epiphysis and perpendicular to the physis (Fig. 19-5B). With an SCFE, the epiphysis is posteriorly displaced relative to the femoral neck, and the guide pin in the lateral

projection angles from anterior to posterior. This is opposite that of a femoral neck fracture where it angles from posterior to anterior. Thus, the two skin lines intersect on the anterolateral aspect of the thigh (Fig. 19-5C), and as the slip becomes more severe, the intersection point becomes more anterior. Due to retroversion of the posteriorly displaced epiphysis in SCFE, the osseous entry point of the guide pin is on the anterior aspect of the femur. In mild SCFEs, it is often at the anterior intertrochanteric line; in severe SCFEs, it moves up onto the anterior femoral neck.

projection angles from anterior to posterior. This is opposite that of a femoral neck fracture where it angles from posterior to anterior. Thus, the two skin lines intersect on the anterolateral aspect of the thigh (Fig. 19-5C), and as the slip becomes more severe, the intersection point becomes more anterior. Due to retroversion of the posteriorly displaced epiphysis in SCFE, the osseous entry point of the guide pin is on the anterior aspect of the femur. In mild SCFEs, it is often at the anterior intertrochanteric line; in severe SCFEs, it moves up onto the anterior femoral neck.

FIGURE 19-4 An intraoperative photograph of an SCFE patient properly positioned on the fracture table. A. The AP position of the fluoroscope. B. The cross-table lateral position of the fluoroscope. |

FIGURE 19-5 A guide pin is placed onto the skin overlying the hip such that the pin is positioned in the center of the epiphysis and perpendicular to the physis in both AP and lateral images. The intraoperative fluoroscopic images with the guide pin over the hip on the skin and the correct position of the pin relative to the epiphysis—in the center and perpendicular to the physis on both AP (A) and lateral (B) images. Lines are drawn along the pin on the skin. The two skin lines intersect on the anterolateral aspect of the thigh (C). (A and B

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|