CHAPTER 37 Pediatric Pelvic Osteotomies and Shelf Procedures

Indications

Surgical techniques

Rotational Osteotomies

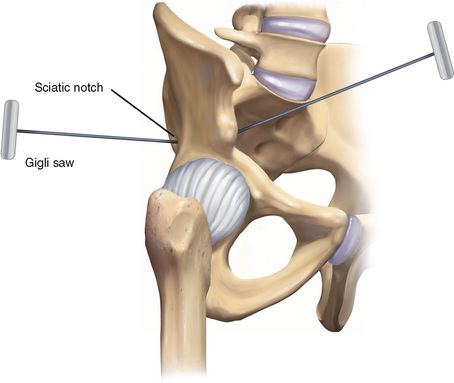

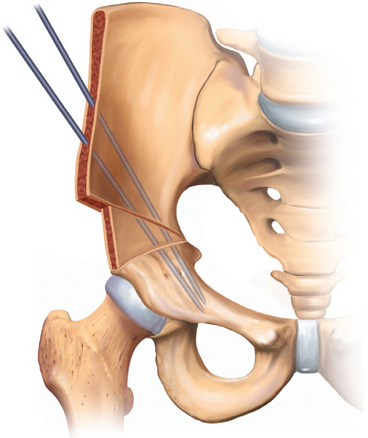

The patient is placed in the supine position with a sandbag under the ipsilateral thorax, and the affected limb is draped free. Adductor contracture is released with a subcutaneous or open tenotomy. Incision and exposure are provided via a Smith-Peterson approach to the hip. A so-called bikini incision starts 2 cm distal to the center of the iliac crest, extends 1 cm distal to the anterosuperior iliac spine, and ends below the middle of the inguinal ligament. The interval between the tensor fascia latae and the sartorius is developed to expose the rectus femoris and the anteroinferior iliac spine. The iliac apophysis is incised down to bone along the iliac crest from the posterior end of the skin incision to the anteroinferior iliac spine. The lateral portion of the apophysis and the periosteum of the outer table are carefully stripped in a continuous sheet to the lateral edge of the acetabulum and posteriorly to the greater sciatic notch; this space is then packed. Adhesions of the joint capsule to the lateral aspect of the ilium can be freed with a periosteal elevator. The medial half of the apophysis and the periosteum of the inner wall are carefully stripped in a continuous sheet to expose the sciatic notch. Care is taken to remain subperiosteal to avoid injury to the sciatic nerve and the superior gluteal artery. The tendinous portion of the iliopsoas is exposed on its deep surface at the level of the pelvic brim and rolled over to visualize the musculotendinous junction. A scissors is passed between the tendon and the musculotendinous junction, and the tendon is cut sharply with a scalpel. The tip of a curved forceps is passed subperiosteally from the medial side and through the sciatic notch to grasp the end of the Gigli saw. The index finger of the opposite hand is used to guide the forceps. The skin and the soft tissues are retracted widely. The osteotomy extends in a straight line from the sciatic notch to the anteroinferior iliac spine, with care taken to remain at right angles to the vertical axis of the ilium. The hands are kept far apart, and continuous tension is placed on each end of the saw to keep it from binding (Figure 37-1). A triangular-shaped bone graft is then taken from the iliac crest with large bone cutters. (A saw may be used in older children.) The base of the graft extends from the anterosuperior iliac spine to the anteroinferior iliac spine. A towel clip is placed on each fragment. The proximal fragment should only be steadied. The towel clip on the distal fragment should be placed well posterior to avoid fracture. The distal fragment is then rotated downward and forward in line with the ilium, which opens the osteotomy anterolaterally. Avoid the posterior or medial displacement of the distal fragment. If the hip capsule has not been opened, the leg can be used to attain the desired correction by placing it in a figure-four position. Downward pressure on the knee as the heel is moved toward the child’s chin produces the desired rotation. The wedge-shaped bone graft is then inserted into the osteotomy site, and the traction is released from the distal fragment. The posterior aspect of the osteotomy should remain closed. Two heavy, threaded K-wires are inserted across the osteotomy site, through the graft, and into the distal segment that lies medial and posterior to the acetabulum (Figure 37-2). Care is taken to avoid penetrating the hip joint. The hip is carefully moved so that crepitus can be heard and felt for; this may indicate that a pin has penetrated the joint. The two halves of the iliac apophysis are sutured together. The K-wires are cut so that their ends lie in subcutaneous fat. A drain is usually not necessary if only an innominate osteotomy has been performed. The wound is then closed. A 1½ hip spica cast is applied with the hip in slight abduction, flexion, and internal rotation and with the knee in flexion. In older, reliable children, three-point partial weight bearing with crutches may be permitted with no immobilization.

Osteotomies in which all three pelvic bones (e.g., Steel, Tönnis, Carlioz) are cut offer greater rotational advantages. The Ganz periacetabular osteotomy may be performed for patients with a closed triradiate cartilage. This procedure is discussed in detail in Chapter 26, and it will not be discussed here. Variations of the triple osteotomy exist for patients with open triradiate cartilage.

Volume-Reducing Osteotomies

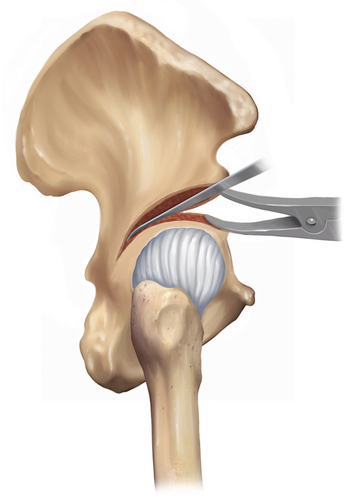

The patient is positioned supine, with a bump placed under the involved hip. Exposure is via a Smith-Peterson approach to the hip. Just as with the Salter osteotomy, the iliac apophysis is split, and both the inner and outer tables of the ilium are exposed subperiosteally. Exposure is carried out to the sciatic notch, and the rectus insertion is left alone. Although it was not recommended by Pemberton in his original article, the division of the psoas tendon (as in the Salter osteotomy) may facilitate correction. Two flat-blade retractors are inserted into the sciatic notch on either side of the ilium. The osteotomy is performed with a narrow curved osteotome through the outer table, starting 1 cm above the anteroinferior iliac spine and extending posteriorly, keeping 1 cm to 1.5 cm from the attachment of the hip capsule. Because the osteotomy is carried posteriorly and then inferiorly through the outer table, it will disappear into the soft-tissue attachments behind the capsule. Visualization can be facilitated by the rotation of the retractor in the sciatic notch. Care must be taken to avoid cutting into the sciatic notch. Direct the osteotomy to the ilioischial limb of the triradiate cartilage. With the use of the same osteotome, a corresponding cut is made on the inner table. As with the outer table, avoid cutting into the sciatic notch. The plane of the osteotomy may be adjusted on the basis of the type of coverage that is necessary. A more transverse cut will provide more anterior coverage, whereas a laterally inclined osteotomy will provide more lateral coverage. After both cortices of the ilium have been cut, a wide curved osteotomy is used to connect the two cuts. As the osteotome proceeds posteriorly, it will become apparent that it cannot make the sharp turn inferiorly into the posterior column. A special Pemberton right-angled curved osteotome is used to complete this cut into the triradiate cartilage (Figure 37-3). A small lamina spreader can hold the osteotomy apart and facilitate this cut. The acetabulum can now be directed into the desired position. A groove is cut into each surface of the osteotomy with a narrow gouge or curette. A triangular wedge of bone is removed from the anterior iliac crest and placed in the osteotomy site (Figure 37-4). Because the graft will be recessed in the osteotomy site, the graft should be larger than the gap created by the osteotomy. This osteotomy is quite secure, and it does not require additional fixation. The iliac apophysis is reapproximated, and the wound is closed. The patient is placed in a 1½ hip spica cast.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree