Pectoralis Major Tendon Ruptures

George K. Bal MD, FACS

Carl J. Basamania MD

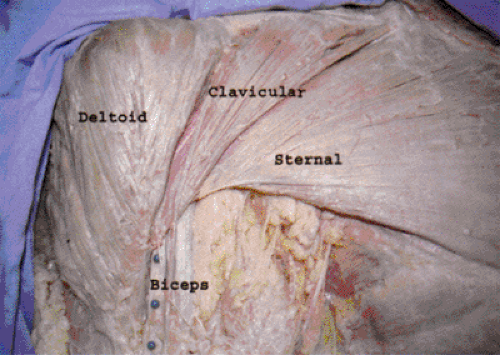

The pectoralis major muscle demonstrates two distinctively different parts—the clavicular head and the sternal head.

The clavicular head arises from the medial clavicle and upper sternum. It is supplied by the pectoral nerve off of the lateral cord and the deltoid branch of the thoraco-acromial artery.

The sternal head arises from the sternum, upper six ribs, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. It is supplied by the medial pectoral nerve (C8-T1) off of the medial cord.

The most common mechanism for sustaining a pectoralis muscle injury is from weight-training or athletics.

The patient typically presents after sudden onset of pain in the shoulder. Acutely injured patients have limited shoulder range of motion; however, the more chronic injuries typically have a full range of motion. In more chronic injuries, deformity is obvious with noticeable skin retraction and loss of anterior axillary fold.

Imaging of soft-tissue injury in the pectoralis major can be difficult. Plain x-rays can reveal bone avulsions, or loss of pectoralis shadow. Ultrasound can demonstrate intra-muscular injury or loss of continuity of tendon. Hematoma is easily identified in acute injuries.

Young, athletic patients will generally not tolerate the persistent weakness and cosmetic deformity that goes with pectoralis major ruptures; however, elderly or low-demand patients with pectoralis ruptures can be treated conservatively with success.

The primary goal of surgical repair should be solid tendon apposition to bone.

Postoperatively, the arm is placed in a sling. Patients are encouraged to perform limited activities of daily living as tolerated. Gentle ROM exercises begin immediately, avoiding early passive external rotation or abduction.

Patients with acutely repaired tendon ruptures may return to full activity 4 to 6 months after repair. Elite weight lifters with chronically repaired tendon ruptures may not be able to return to pre-injury levels.

The anatomy of the pectoralis major muscle demonstrates two distinctively different parts—the clavicular head and the sternal head (Fig 16-1). We feel that when evaluating injuries to the pectoralis it is important to understand the anatomy of the pectoralis major muscle complex. Unfortunately, many of the published reports never comment on this difference, or describe it incompletely and do not distinguish if a ‘complete’ tear involves one or both heads of the pectoralis (1,2). Only a small number of reports specifically address the anatomy of the pectoralis and the relation of the two heads (3,4,5). Wolfe et al. (5) suggested the human pectoralis major to be evolved from two distinctly separate muscles in lower mammals. The sternal head of the pectoralis muscle arises from the sternum, upper six ribs, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. The sternal head is supplied by the medial pectoral nerve (C8-T1) off of the medial cord, and specific pectoral artery. The clavicular head of the pectoralis major arises from the medial clavicle, and upper sternum. The clavicular head is supplied by the lateral pectoral nerve (C5-C7) off of the lateral cord, and the deltoid branch of the thoraco-acromial artery. The sternal head primarily performs

adduction and internal rotation; the clavicular head assists with forward elevation. The two portions of the muscle form a bi-laminar tendon that inserts lateral to the long head biceps tendon. The clavicular head tendon inserts anterior and slightly distal; the sternal head folds posterior and extends superiorly. To further suggest that these are distinctly different muscles, Poland’s Syndrome involves the absence of only the sternal portion of the pectoralis muscle (6), although the clavicular head is present. The primary deformity and associated weakness seen in pectoralis ruptures is related to loss of the sternal head tendon.

adduction and internal rotation; the clavicular head assists with forward elevation. The two portions of the muscle form a bi-laminar tendon that inserts lateral to the long head biceps tendon. The clavicular head tendon inserts anterior and slightly distal; the sternal head folds posterior and extends superiorly. To further suggest that these are distinctly different muscles, Poland’s Syndrome involves the absence of only the sternal portion of the pectoralis muscle (6), although the clavicular head is present. The primary deformity and associated weakness seen in pectoralis ruptures is related to loss of the sternal head tendon.

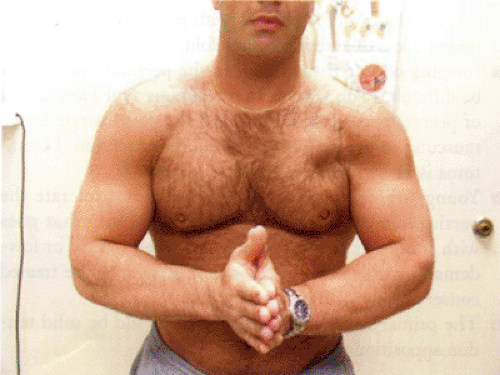

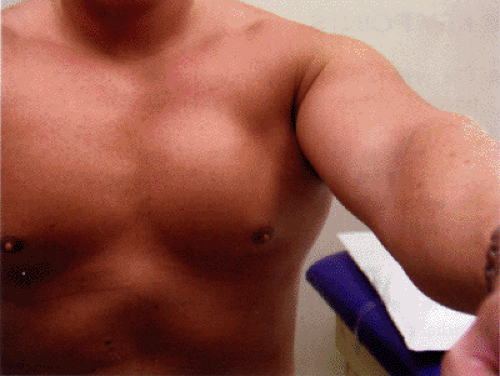

The most common mechanism for sustaining a pectoralis muscle injury is from weight-lifting or athletics. Wolfe et al. (5) described the transition period from eccentric loading to concentric loading (bench press position) as the most stressful to the inferior muscle fibers of the pectoralis muscle. The patient typically presents after sudden onset of pain in the shoulder. Acutely injured patients have limited shoulder range of motion; however, the more chronic injuries typically have a full range of motion. A large ecchymoses may be present on the lateral chest, but commonly extends onto the upper arm (Fig 16-2). Without a careful exam, the rupture can be misdiagnosed as a biceps tendon injury (7). Acutely, it may be difficult to see a deformity in the lateral chest secondary to swelling. The classic loss of the anterior axillary fold and lateral chest border is seen in chronic injuries with either sternal head ruptures, or complete pectoralis ruptures. Often the avulsed tendon end is palpable on the chest wall. In more chronic injuries the deformity is usually obvious, with noticeable skin retraction and loss of the anterior axillary fold. Sternal head ruptures can be differentiated from complete ruptures by careful clinical exam. With forward elevation, the clavicular head of the muscle can be both palpated and visualized (Fig 16-3). Resisted adduction or internal rotation will reveal the deficient sternal head (Fig 16-4).

Fig 16-2. Diffuse ecchymoses from pectoralis major rupture. Note discoloration seen on distal arm and lateral chest. |

Fig 16-3. Intact clavicular head and retracted sternal head of pectoralis major. Demonstrated with resisted forward elevation. |

Imaging of the soft tissue injury in pectoralis major ruptures can be difficult. Plain x-rays can reveal bone avulsions, or loss of the pectoralis shadow. Ultrasound exam can demonstrate intra-muscular injury or loss of continuity of the tendon (8). CT scan can outline the muscle, but has difficulty visualizing the distal soft tissue of the pectoralis. MRI has been demonstrated to reliably identify injury to the muscle and distal tendon (9) (Fig 16-5). Acute injury and edema of the pectoralis muscle, however, and insertion can make identification of a complete rupture difficult (10). The hematoma is easily identified in acute injuries, but is not present in more chronic tears. It can also be difficult to differentiate a sternal head rupture versus complete injury. Incomplete tendon injuries and medial muscle ruptures are not usually amenable to repair. In our practice, we have not found MRI results to significantly affect our pre-operative planning. In general, most of the information required for surgical decision-making can be obtained from the physical exam.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree