CHAPTER 29 Pathology and findings in patients with multidirectional instability

Classification of shoulder instability is best thought of as lying on a spectrum bound by the extremes of traumatic, unidirectional instability and asymptomatic, generalized laxity.

Classification of shoulder instability is best thought of as lying on a spectrum bound by the extremes of traumatic, unidirectional instability and asymptomatic, generalized laxity. Patients with multidirectional instability (MDI) often have unilateral symptoms and a traumatic, inciting event that compromises glenohumeral concavity-compression.

Patients with multidirectional instability (MDI) often have unilateral symptoms and a traumatic, inciting event that compromises glenohumeral concavity-compression. Findings in patients with MDI include lesions of the labrum (SLAP lesions, Bankart lesions, Kim lesions, extensive labral tears), capsule (HAGL lesions), and humeral head (Hill Sachs).

Findings in patients with MDI include lesions of the labrum (SLAP lesions, Bankart lesions, Kim lesions, extensive labral tears), capsule (HAGL lesions), and humeral head (Hill Sachs). Findings in patients with MDI include Hill-Sachs lesions, suggesting that a significant number of these patients have had shoulder dislocations to precipitate their MDI.

Findings in patients with MDI include Hill-Sachs lesions, suggesting that a significant number of these patients have had shoulder dislocations to precipitate their MDI. Studies of patients who have generalized laxity and instability of the shoulder have demonstrated imbalances in muscle coordination and deficits in shoulder joint proprioception.

Studies of patients who have generalized laxity and instability of the shoulder have demonstrated imbalances in muscle coordination and deficits in shoulder joint proprioception.Introduction

Traditional classifications of shoulder instability are often based on etiology (traumatic versus atraumatic) and direction of instability (anterior, posterior, or multidirectional). Although this method of description may be appropriate for the most common form of shoulder instability—traumatic, anterior instability—it does not appropriately describe the spectrum of pathology known as multidirectional instability (MDI). Patients with MDI do not often fit neatly into conventional categorization. Unlike their traumatic counterparts, these patients can present following atraumatic events. On the other hand, Neer et al have cautioned against a purely atraumatic concept of MDI, indicating that such thinking could often lead to misdiagnosis.1 The various etiologic events that may lead to MDI make this a less than straightforward condition to understand and diagnose.

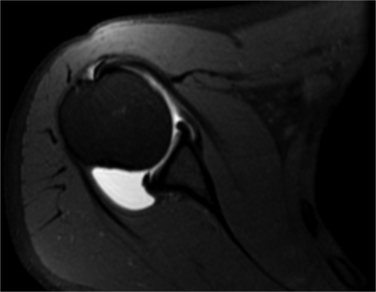

Whereas the prominent pathologic lesion associated most commonly with traumatic, anterior shoulder instability is the labral (Bankart) lesion, the essential lesion of MDI involves the glenohumeral capsule. The common finding in all cases of MDI involves a pathologic laxity of the capsule, which manifests in an enlargement of capsular volume (Fig. 29-1). In addition to this characteristic finding, a cluster of other pathologic lesions has been associated with MDI, making its diagnosis more complex than its unidirectional counterpart.

Pathology

The pathology exhibited by the patient with MDI can range across a spectrum bound by the extremes of traumatic, unidirectional instability and asymptomatic, generalized joint laxity. As our understanding of shoulder instability progresses, it becomes apparent that the classic “AMBRI” acronym (Atraumatic, Multidirectional, Bilateral, Rehabilitation, Inferior capsular shift) does not apply to all cases of the shoulder with MDI. Despite the fact that most cases of MDI do not present with a history of a frank glenohumeral dislocation, the clinical history of a patient with this form of instability will quite often reflect a traumatic, formative event. Often the patient will recall a “minor” injury in the gym, a repetitive activity such as swimming or serving a tennis ball, or a lifting “sprain,” which may have precipitated a cascade of recurring symptomatic instability. Neer et al reported that the initial dislocation in their 40 patients with MDI occurred with varying degrees of injury: minor injury in 7 patients, moderate injury in 21 patients, and severe injury in 8 patients.1 Once the equilibrium maintained by the balance of dynamic and static shoulder stabilizers is lost, it is often difficult to regain. A single episode of subluxation can injure the joint capsule and adversely influence neuromuscular control exerted by the rotator cuff.2 This loss of glenohumeral concavity-compression leads to more instability.

Physical examination

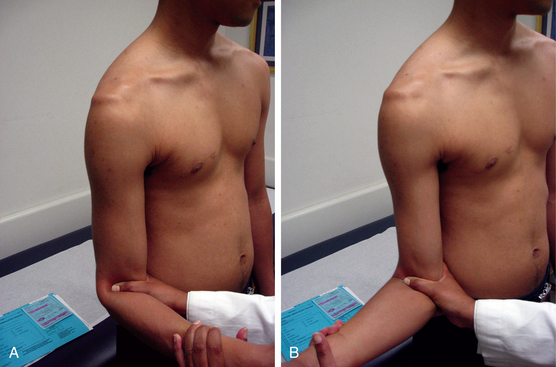

Although the shoulder with MDI will often demonstrate multiplanar laxity on physical examination, the pattern of instability is often dominated by a single direction. The examiner should be careful not to confuse laxity (physiologic) with instability (pathologic). The MDI shoulder will often test positive with the hallmark tests for laxity: a positive sulcus test signifying deficiency of the rotator interval if it persists in external rotation (Fig. 29-2), push-pull test, and load-and-shift test indicating a multiplanar pattern. Although this laxity may be dramatic, it is often asymptomatic. During examination, clinical symptoms are generally reproduced when provoking one or the other single-plane instability tests (i.e., apprehension/relocation test or jerk test) not both. Controversy exists about whether multidirectional and unidirectional instability are always distinct conditions or just one extreme on a continuum of joint laxity.3 MDI patients demonstrate laxity in midrange shoulder positions.4 Therefore, symptoms are more often experienced during activities of daily living and as such, are more functionally incapacitating compared with the symptoms in patients with other types of instability.5,6

Despite demonstrating bilateral signs of shoulder laxity, most patients with MDI present with unilateral symptoms. Patients usually report recurrent subluxation and a sense of instability rather than a locked dislocation. Following activities that involve lifting, pushing or pulling, patients with MDI may complain of a vague shoulder “heaviness” or distal paresthesias as a result of traction on the brachial plexus. In two published series of patients with MDI, bilateral surgery was required in only 11% and 13% respectively, further emphasizing the multifactorial nature of this disorder.1,7

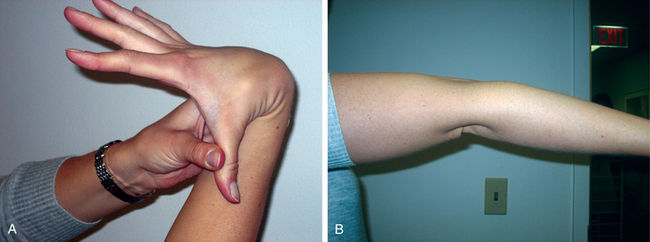

The underlying condition described as generalized ligamentous laxity often accompanies the cluster of clinical findings that the patient with MDI usually exhibits (Fig. 29-3). Several authors have demonstrated that the collagen in the capsular tissue of patients with MDI may be altered.8,9 Imazato and Hirakawa correlated the relationship between patients with excessive shoulder laxity and the presence of more soluble, less cross-linked collagen fibers in these patients’ capsule, muscles, and skin when compared to a control group.8,9 It has been suggested that the presence of a recognized connective tissue disorder (i.e., Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or Marfan syndrome) in patients being treated for MDI has been associated with high failure rates following soft-tissue stabilization procedures5 (Table 29-1).

FIGURE 29-3 Generalized hyperlaxity signs—thumb to forearm (A) and hyperextension of the elbows (B).

Table 29-1 Beighton Score for Hyperlaxity

| Passive hyperextension of the small finger | 2 | >90 degrees |

| Passive thumb to forearm | 2 | Thumb touches forearm |

| Elbow hyperextension | 2 | >10 degrees |

| Knee hyperextension | 2 | >10 degrees |

| Standing trunk flexion with knees locked in extension | 1 | Both palms flat on floor |

Findings

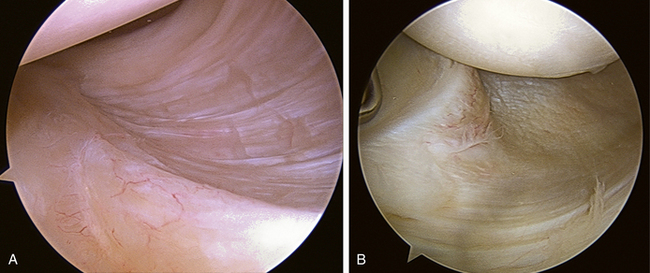

The dominant abnormality in the shoulder with MDI is capsular laxity, resulting in a global increase in capsular volume, particularly inferiorly (Fig. 29-4). Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that the inferior capsule resists inferior translation increasingly as the shoulder is abducted to 90 degrees, explaining the associated findings of laxity on physical examination (i.e., push-pull test, sulcus test).10 Although the general description of the capsular defect associated with MDI has been described as “excessively compliant” or “capacious,” the common denominator in all patients with MDI appears to be the excessive capsular volume that these lesions produce11 (Fig. 29-5). Specific capsular lesions have been described in the MDI shoulder. Dewing et al demonstrated capsular elongation in patients with MDI using magnetic resonance arthrography.12 Alpert et al described a humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesion; Kim et al have described the hidden posteroinferior lesion of the capsulolabral complex in many of their patients with MDI.13,14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree