Patellofemoral Arthroplasty

Jess H. Lonner

Epidemiological studies show that isolated patellofemoral arthritis may occur in as many as 9% of patients over the age of 40 and in 15% of patients 60 and older (1). Women who present with symptomatic knee arthritis are more likely than men to have the degeneration localized to the patellofemoral compartment. In patients over the age of 55, arthritis may be restricted to the patellofemoral compartment in 24% of women compared to 11% of men (2). These patients frequently seek orthopedic treatment.

Many cases of patellofemoral arthritis are typically treated adequately with measures such as activity modification, physical therapy, oral medications, and injections. However, patellofemoral arthroplasty (PFA) may be beneficial when nonoperative interventions are ineffective. Other surgical alternatives to PFA have had inconsistent success managing patellofemoral arthritis. Arthroscopic lavage and debridement, with or without marrow stimulation, has had satisfactory short-term results in only approximately 40% to 60% of patients (3). “Biologic” approaches for isolated patellofemoral arthritis, including autologous chondrocyte implantation and fresh osteochondral allografting, as well as tibial tubercle unloading procedures (direct anteriorization and anteromedialization) have had 25% to 30% unsatisfactory results at short-term follow-up (4, 5, 6, 7). Patellectomy reduces knee extension power, and tibiofemoral joint reaction forces have been shown to increase as much as 250% after patellectomy, which increases the risk for the development of tibiofemoral arthritis (8). Variable pain relief, substantial residual quadriceps weakness, secondary instability, an early failure rate as high as 45% after patellectomy, and a tendency for relatively poor outcomes after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in patients who had previously undergone patellectomy (9,10), have led to the abandonment of the procedure except perhaps in very unusual circumstances. TKA is an effective treatment option for elderly patients with isolated patellofemoral arthritis; however, it may not be desirable for all patients (11). In many patients with isolated patellofemoral arthritis and no tibiofemoral disease, I prefer to perform PFA because of its conservative nature, kinematic preservation, quick recovery, and clinical success.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

The success of PFA is, in part, contingent on appropriate patient selection. After a reasonable attempt at nonoperative measures, the procedure can be considered for patients with isolated patellofemoral osteoarthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, or advanced chondromalacia (Outerbridge grade IV) on either or both the trochlear and patellar surfaces. PFA is very effective in the presence of patellar or trochlear dysplasia (12,13), although some implant designs are more appropriate in the setting of dysplasia than others (14,15). Slight patellar tilt or subluxation observed on preoperative tangential radiographs or intraoperatively (with a normal Q angle) can usually be addressed effectively with a lateral retinacular release, medialization of the patellar component, and resection of the lateral patellar facet.

In the past, my personal preference was to restrict PFA to patients younger than 55 or 60 (12,14). Subsequently, however, I have treated a number of patients between the ages of 60 and 85, and the results of PFA have been excellent in that cohort. Additionally, there are no published data showing that the results differ in younger and older patients.

PFA is contraindicated in patients with considerable medial and lateral joint line pain. Any evidence of tibiofemoral arthritis or advanced chondromalacia is a contraindication to the use of isolated PFA, although combining PFA with chondral resurfacing for focal defects of the weight-bearing condylar surfaces or with unicompartmental arthroplasty for more advanced tibiofemoral arthrosis are emerging strategies (12,16). It is not appropriate for patients with inflammatory arthritis or those with chondrocalcinosis of the menisci or weight-bearing surfaces of the tibiofemoral compartments. I would also avoid this in patients who have severe coronal deformity unless corrected, because it may negatively affect patellar tracking and predispose to early development of tibiofemoral arthritis. The patellofemoral prosthesis cannot be expected to stabilize a highly malaligned patellofemoral articulation; therefore, the presence of a very high Q angle is a relative contraindication to PFA unless a tibial tubercle anteromedialization is performed before or simultaneous with PFA. Patients with inappropriate expectations regarding the extent of pain relief, duration of recovery, and allowable activities after they have recovered from PFA may not be suitable candidates for the procedure (12).

It is unknown at this time whether obesity or cruciate ligament insufficiency have deleterious effects on the outcomes of PFA. Intuitively, the former condition may predispose to implant wear or loosening, and both conditions may predispose to early tibiofemoral arthritis. I have successfully performed PFA in mildly obese patients but not morbidly obese patients, particularly because in my experience, morbidly obese patients often tend to have tibiofemoral pain in addition to patellofemoral pain, even when radiographically, the preponderance of arthritis affects the patellofemoral compartment.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

It is necessary to ensure that the pain and arthritis are, in fact, localized to the patellofemoral compartment, which can be done primarily by taking a thorough history and performing a meticulous physical examination. Patients will typically report anterior knee pain and crepitus (often retropatellar and medial and lateral peripatellar), which is exacerbated when sitting with the knee flexed, standing from a seated position, walking up and down hills and stairs, and squatting. There is typically much less or even no pain when walking on level ground. A key detail of the patient’s history should include whether there was previous trauma to the knee, a history of patellar dislocation, or prior patellofemoral problems. A history of recurrent atraumatic patellar dislocations may suggest considerable malalignment, which may need to be corrected before PFA.

On physical examination, there is pain on patella inhibition testing, patellofemoral crepitus, and retropatellar knee pain with squatting. Any medial or lateral tibiofemoral joint line tenderness raises my suspicion of more diffuse chondral disease (even in the presence of relatively normal radiographs), and I consider this a contraindication to PFA except in circumstances when the pain appears to be referred from the arthritic patellofemoral surfaces. Other potential sources of anterior knee pain, such as pes anserinus bursitis, patellar tendonitis, and prepatellar bursitis, or pain referred from the ipsilateral hip or back, should be excluded.

Generally, weight-bearing radiographs are ample imaging studies to aid in the diagnostic evaluation and subsequent surgical planning (Fig. 26-1A-D). Standing anteroposterior (AP) and midflexion posteroanterior radiographs will not allow visualization of the patellofemoral compartment of the knee, but they help establish the presence or absence of tibiofemoral arthritis. The standing midflexion posteroanterior view is particularly useful in showing whether there is posterior condylar wear, especially in patients who may have occasional tibiofemoral pain. Axial and lateral radiographs will demonstrate the presence of patellofemoral arthritis, whether there is patella alta or baja, and whether there is patella tilt or subluxation. Occasionally, the axial radiograph will underestimate the extent of patellofemoral arthritis if the full-thickness cartilage defects are shouldered by relatively intact cartilage on both the trochlear and patellar surfaces in the angle at which the radiograph is taken. Occasionally, subchondral sclerosis and facet “flattening” may be the only radiographic clues that there is patellofemoral arthritis. Computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging are not typically necessary. Occasionally, patients have had prior arthroscopic intervention, and photographs and surgical reports from these procedures provide important information regarding the extent of patellofemoral arthritis and the status of the tibiofemoral compartments.

Assessment of patellar tracking and the Q angle is also important. It is my opinion that an excessive Q angle (more than 20 degrees in women and 15 degrees in men) needs to be corrected either

before or simultaneous with PFA. If the choice is made to correct the Q angle with a tibial tubercle anteromedialization at the time of PFA, provisions need to be made beforehand to have an appropriate set of drills and screws available for tubercle fixation, as well as fluoroscopic imaging.

before or simultaneous with PFA. If the choice is made to correct the Q angle with a tibial tubercle anteromedialization at the time of PFA, provisions need to be made beforehand to have an appropriate set of drills and screws available for tubercle fixation, as well as fluoroscopic imaging.

FIGURE 26-1 (A-D) Standing anteroposterior, midflexion posteroanterior, lateral, and sunrise radiographs of the left knee show isolated patellofemoral arthritis. |

If a small area of full-thickness chondromalacia is found on the weight-bearing surfaces of the femoral condyles during PFA, autologous osteochondral grafting can be performed, harvesting an osteochondral plug from either a relatively unaffected area of the trochlea that is being removed for the trochlear implant or from the edge of the intercondylar notch (16). Therefore, a cylindrical osteochondral plug harvesting system should be available during the procedure, and the surgical consent form should reflect the possibility of this additional procedure. Additionally, occasionally patients are advised that an intraoperative decision may be made to combine the PFA with a unicompartmental arthroplasty or to perform a TKA instead. These alternatives are appropriate if there is more extensive medial and/or lateral arthritis than anticipated (although typically this would be predictable beforehand, based on the physical examination and radiographs). In cases when these additional or alternative procedures may be necessary, the surgical consent should reflect these possibilities, and additional implant systems and sets should be ordered in advance.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

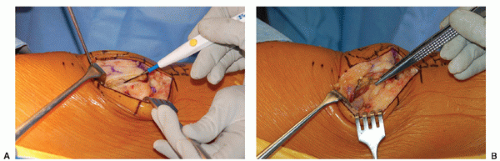

The knee is approached through a midline or anteromedial skin incision and a medial arthrotomy (Fig. 26-2A,B). My preference is a minimally invasive approach, although I recommend that early in a surgeon’s experience, the skin incision should be a traditional extensile length incision with a

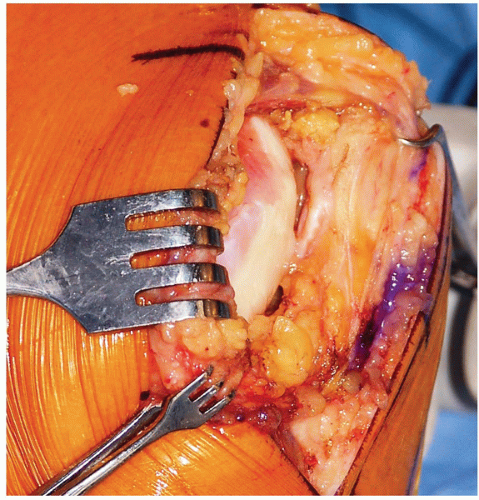

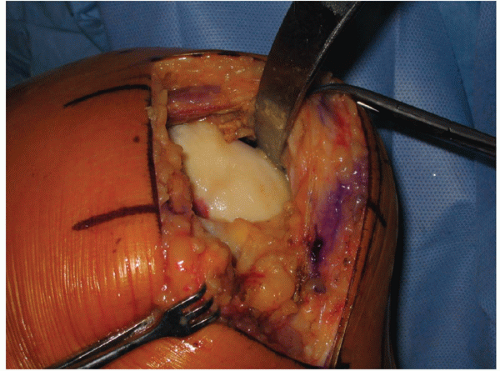

standard arthrotomy to achieve ample exposure and become familiar with the nuances of the surgical technique and instrumentation without being distracted by a less-invasive surgical approach. The skin incision I use typically extends from 1 to 2 cm above the tibial tubercle to 1 to 2 cm proximal to the patella, but it can be extended liberally depending on the challenge of the procedure and appearance of the proximal and distal skin edges. I typically use either a mini-midvastus or mini-subvastus arthrotomy (Fig. 26-3A,B). The infrapatellar fat pad can be partially excised to facilitate exposure, while taking care to avoid cutting normal articular cartilage, menisci, or the intermeniscal ligament at the time of arthrotomy (Fig. 26-4). Before proceeding with PFA, carefully inspect the entire joint to make sure that the arthritis is restricted to the patellofemoral compartment and the tibiofemoral compartments are free of disease (Figs. 26-5 and 26-6; see Figs. 26-13 and 26-28). If a minimally invasive approach is used, a “mobile window” concept is utilized, adjusting retraction on the soft tissues to visualize separately either the medial or lateral compartments. With broader exposure, visualization of all compartments of the knee is achievable at once. Release of the lateral patellofemoral synovial ligaments facilitates patellar eversion, if the surgeon prefers to do so, and it removes a

potential lateral tether on the patella. This is not a lateral retinacular release, although it may also help to optimize patellar tracking (Fig. 26-7).

standard arthrotomy to achieve ample exposure and become familiar with the nuances of the surgical technique and instrumentation without being distracted by a less-invasive surgical approach. The skin incision I use typically extends from 1 to 2 cm above the tibial tubercle to 1 to 2 cm proximal to the patella, but it can be extended liberally depending on the challenge of the procedure and appearance of the proximal and distal skin edges. I typically use either a mini-midvastus or mini-subvastus arthrotomy (Fig. 26-3A,B). The infrapatellar fat pad can be partially excised to facilitate exposure, while taking care to avoid cutting normal articular cartilage, menisci, or the intermeniscal ligament at the time of arthrotomy (Fig. 26-4). Before proceeding with PFA, carefully inspect the entire joint to make sure that the arthritis is restricted to the patellofemoral compartment and the tibiofemoral compartments are free of disease (Figs. 26-5 and 26-6; see Figs. 26-13 and 26-28). If a minimally invasive approach is used, a “mobile window” concept is utilized, adjusting retraction on the soft tissues to visualize separately either the medial or lateral compartments. With broader exposure, visualization of all compartments of the knee is achievable at once. Release of the lateral patellofemoral synovial ligaments facilitates patellar eversion, if the surgeon prefers to do so, and it removes a

potential lateral tether on the patella. This is not a lateral retinacular release, although it may also help to optimize patellar tracking (Fig. 26-7).

FIGURE 26-5 The mobile window strategy can be used to assess the tibiofemoral articular surfaces if a minimally invasive approach is used. Here, the medial femoral condyle is noted to be intact. Alternatively, if a slightly more extensile arthrotomy is used, broad visualization of both condyles simultaneously is possible (see Fig. 26-8). |

If a femoral condylar defect is noted in addition to the patellofemoral arthritis, an osteochondral plug can be harvested from a relatively healthy area of the trochlear surface or from around the intercondylar notch. The size of the condylar lesion is determined, and it is removed with a cylindrical coring system. A second cylindrical harvester with a diameter measuring approximately 1 mm larger than the defect is used to harvest the donor osteochondral plug, which is then implanted into the recipient site, leaving it flush with the surrounding articular cartilage (Figs. 26-8, 26-9, 26-10 and 26-11).

The proximal extent of the trochlea is demarcated using electrocautery, anterior synovial tissue excised from the area on which the trochlear component will be implanted, and osteophytes removed from the intercondylar notch (Fig. 26-12). One of the more critical components of the procedure is ensuring that the trochlear component is externally rotated perpendicular to the AP axis (Whiteside’s line) of the distal femur. The AP axis is a line drawn from the low point of the anterior surface of the trochlear groove to the highest point of the intercondylar notch (Fig. 26-13). If the trochlear surface is extremely dysplastic, and if the sulcus of the trochlear groove is indeterminable, the trochlear component is implanted parallel to the transepicondylar axis. This is a line drawn from the sulcus of the medial epicondyle to the prominence of the lateral epicondyle. A slightly more extensile incision may be necessary to identify these landmarks.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|