Parotitis

Ellen R. Wald

Inflammation of the parotid gland may result from infectious or noninfectious causes. In children, most single attacks of parotitis result from viral infection of the gland. This chapter is divided into considerations of viral parotitis, suppurative parotitis, and recurrent parotitis.

VIRAL PAROTITIS

Before the availability of the Jeryl Lynn vaccine, licensed in 1967, the most common cause of parotitis in children was infection with mumps virus, a myxovirus categorized in the same group of RNA viruses as that listing influenza and parainfluenza viruses. After vaccine licensure, it became apparent that other viruses—parainfluenza types 1 and 3, influenza A and B, coxsackieviruses A and B, echoviruses, Epstein-Barr virus, and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus—could cause parotitis. Parotitis may be seen also as one of the protean manifestations of infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Pathogenesis

A myxovirus is transmitted by the respiratory route. After it is acquired, the virus replicates in the epithelial cells of the nasopharynx; subsequently, a viremia occurs, with ultimate localization of virus in the parotid gland.

Clinical Manifestations and Complications

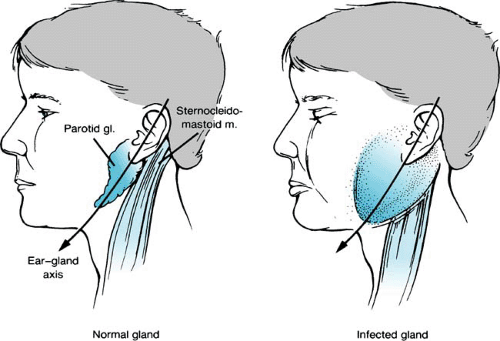

In typical cases of viral parotitis, preschool or school-aged children may have a brief prodrome of such constitutional symptoms as fever, headache, anorexia, and malaise. The initial local complaint is ear pain located near the lobe of the ear and accentuated by chewing movements. Initially, when the parotid gland begins to swell, the sulcus between the mastoid and the mandible is obliterated. The gland enlarges symmetrically in front of and behind the ear, obscuring the angle of the mandible and displacing the lobe of the ear upward and outward (Fig. 259.1). The entire parotid gland becomes swollen in a uniform fashion. The gland peaks in size in 1 to 3 days and can be fairly tender and painful. Visually, the swelling is impressive. On occasion, the swelling is boggy to the touch, and delineating the parotid gland precisely by palpation is difficult. In other patients, the gland is firm and indurated, with a well-demarcated posterior edge. The skin overlying the gland is neither erythematous nor warm, remaining nearly normal in appearance. The orifice of Stensen duct opposite the second molar may be prominent as a consequence of erythema and swelling. Expressed secretions appear clear. Generally, the parotid on one side swells first and then, in several days, the contralateral gland also becomes involved. Unilateral involvement is seen in 25% of cases. Pain, trismus, and dysphagia are common manifestations leading to poor oral intake. The swelling may take 7 to 10 days to subside.

Diagnosis and Therapy

Usually, the diagnosis of viral parotitis is clinical. Culturing the throat for virus may allow a delineation of the precise causative agent. Surprisingly, the amylase level is not always elevated in cases of parotitis. Treatment of viral parotitis is symptomatic. Analgesics may be prescribed. A fluid or soft diet is preferable when the parotid swelling is maximal.

SUPPURATIVE PAROTITIS

Suppurative parotitis is an unusual clinical problem in the pediatric age group. It is most common in neonates, and occurs sporadically in children older than 10 years. The usual predisposing cause is stasis of secretions in the parotid gland. This condition may be secondary to dehydration or to an abnormality of Stensen duct, either a congenital or an acquired malformation, including a sialolith (stone).

Pathogenesis

The most common bacterial isolate in cases of suppurative parotitis is Staphylococcus aureus. Other bacterial species that have been implicated include Streptococcus pneumoniae, alpha- and beta-hemolytic streptococci, enteric gram-negative bacilli, and Haemophilus influenzae. An important role for anaerobic bacterial species (Bacteroides melaninogenicus and Peptostreptococcus species) has been emphasized. The path of infection is thought to be the ascending route; the oral flora gain access to Stensen duct, and stasis of secretions prevents further washing out of organisms. Although cases occasionally occur by the hematogenous route, this process is much less common.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree