Parosteal Osteosarcoma (Juxtacortical Osteosarcoma)

Parosteal osteosarcoma is considered separately from the rest of the osteosarcomas because it is distinctly less malignant and, therefore, has a vastly different clinical behavior. As the name implies, this tumor is located on the outer surface of the cortex of a bone, and some prefer to call it juxtacortical osteosarcoma. The validity of the concept of parosteal osteosarcoma as a distinct clinicopathologic entity demands that the tumor be well differentiated (low grade by Broders method) and that it arise on the surface of bone. Although occasional typical cases had been documented in the literature, it was not until the description of a collected series by Geschickter and Copeland in 1951 that the entity was established. Gradations exist from the even more uncommon completely benign parosteal osteoma through the lesion with minimal evidence of malignancy to the frankly malignant but fairly well-differentiated parosteal tumor. When the diagnosis of sarcoma depends on such subtle changes as are found in some of these tumors, the problem is often difficult.

Osteogenic tumors of a high degree of malignancy histologically (i.e., of high grade by the method of Broders) are occasionally seen predominantly on the surface of a bone, but they do not belong in the category under discussion. Inclusion of tumors that are histologically like the ordinary osteosarcoma or fibrosarcoma will decrease the usefulness of the term parosteal osteosarcoma. These high-grade surface osteosarcomas are discussed in Chapter 11. Periosteal osteosarcoma, as described in Chapter 11, is distinctly different from parosteal osteosarcoma radiographically and histologically.

Ahuja and coauthors and, more recently, Ritschl and coauthors have tended to consider all surface osteosarcomas to be parosteal and have distinguished them by the histologic grade. All authors agree that sarcomas with a high-grade malignancy have a much worse prognosis than is seen with classic parosteal osteosarcoma. Campanacci and coauthors from Bologna, Italy, also considered all surface osteosarcomas to be parosteal, and they graded them and showed prognostic significance of grading. Schajowicz and coauthors agreed with the concept that has been used at Mayo Clinic and have divided the surface tumors into parosteal, periosteal, and high-grade surface type. The terminology used is probably not important so long as the clinical significance of the different types is recognized. We believe that it is best to reserve the term parosteal osteosarcoma for the well-differentiated variety.

Some very rare, extremely well-differentiated osteosarcomas begin within bone. These low-grade central (intramedullary) osteosarcomas are described in Chapter 11. Reference to the radiograph or to the gross specimen is required in differentiating them from parosteal osteosarcomas. In a rare case, it may be difficult or impossible to know whether a low-grade sarcoma started as a parosteal osteosarcoma and invaded bone or was a low-grade intramedullary osteosarcoma from inception. This question is of only academic interest because the prognosis in either case is excellent.

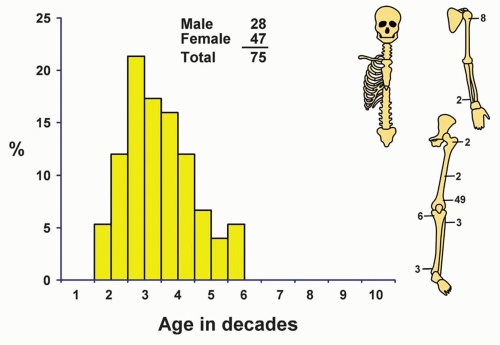

INCIDENCE

Parosteal osteosarcoma is a distinctly rare neoplasm, comprising just over 1% of malignant tumors in our series and just 3.7% of all osteosarcomas (Fig. 12.1).

SEX

In this series, approximately 63% of the patients with parosteal osteosarcomas were females, although males have predominated in some series. Of the 1,952 patients with other types of osteosarcomas in the Mayo Clinic series, approximately 58% were males.

AGE

The average age of patients with this tumor is greater than that of those with ordinary osteosarcoma, a difference that can be explained, at least in part, by the slow growth of parosteal osteosarcoma. Approximately two-thirds of all patients were in the third and fourth decades of life. No patient was in the first decade of life or older than 55 years.

LOCALIZATION

Practically all the recorded parosteal osteosarcomas have involved the femur, the humerus, or the tibia. Other bones, however, may be affected. By far, the most common site for its development is the posterior distal portion of the shaft of the femur, accounting for approximately two-thirds of all the cases in the Mayo Clinic files. In a large series of parosteal osteosarcomas reported by Okada and coauthors, there were rare tumors in unusual sites such as the mandible, the clavicle, and the tarsal bones. When the tumor involves a small or flat bone, it may be impossible to know whether the tumor is truly on the surface of bone.

SYMPTOMS

Swelling is the most important symptom. Frequently, the swelling is painless and may have been present for several years. Because of the location in the popliteal fossa, the patient may note inability to flex the knee. Pain is the second most important symptom, and patients may present with pain without having noted a lump.

A common and practically pathognomonic history is as follows: several years previously, the patient underwent excision of a tumor that had been considered, radiographically, to be atypical osteochondroma. The pathologists regarded it as an unusual osteochondroma and perhaps described it as being cellular. In the interim, the tumor may or may not have required excision because of recurrences. When seen now, the patient has a recurrent, ossified, juxtacortical mass in one of the sites of predilection.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A mass at the lesional site, which is sometimes painful to pressure, is the only significant physical finding. The mass may be very large.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

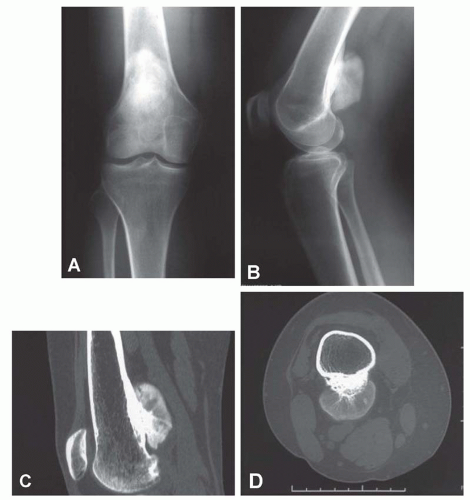

Parosteal osteosarcoma has a pronounced tendency to involve the posterior aspect of the distal femoral shaft. The majority of the tumors involve the metaphysis or metadiaphyseal region. However, a small percentage of tumors involves only the diaphysis of a long bone.

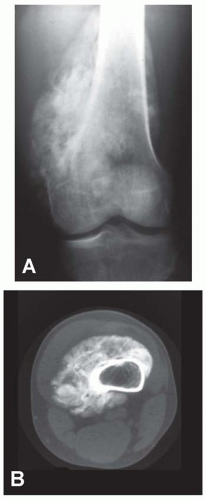

Figure 12.2. Anteroposterior (A) radiograph and computed tomogram (B) of a dedifferentiated parosteal osteosarcoma involving the distal femur in a 43-year-old man. |

The tumor tends to be densely mineralized and the predominant pattern is amorphous, but occasionally, the tumor may show osseous trabeculation. The lesion tends to be lobulated at the periphery, and the outermost portions generally are the least mineralized. However, lucencies may be seen within the substance of the lesion also. Bertoni and coauthors compared the radiographs with macrosections of a series of parosteal osteosarcoma. Their study indicated that the presence of lucency within the substance of the lesion is closely associated with areas of dedifferentiation (Figs. 12.2 & 12.3).

The lesion is attached to the underlying cortex with a broad base. As the lesion enlarges, it tends to grow peripherally and, hence, not attach to the underlying cortex. This usually gives rise to a lucent zone between the growing tumor and the underlying bone. Parosteal osteosarcoma has a remarkable tendency to encircle the underlying bone. The presence of a

very heavily ossified mass encircling a bone may make it difficult to know the exact site of origin. Cross-sectional imaging is very helpful in these surface lesions (Figs. 12.4, 12.5, 12.6 and 12.7).

very heavily ossified mass encircling a bone may make it difficult to know the exact site of origin. Cross-sectional imaging is very helpful in these surface lesions (Figs. 12.4, 12.5, 12.6 and 12.7).

In the study by Okada and coauthors, the underlying cortex was considered to be normal in approximately 50% of the cases. In approximately 25%, the cortex was thickened, and in the rest, it was destroyed.

Parosteal osteosarcoma is considered to be a tumor of the surface of bone. However, the tumor can and does invade the medullary cavity. Medullary involvement is most clearly shown on computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. In the study by Okada and coauthors, 22% of the 37 patients who had cross-sectional studies showed medullary involvement. This medullary involvement was usually slight, and at most, the involvement was no more than 25% of the width of the medullary cavity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree