Palmar Approaches

Michael Darowish

CARPAL TUNNEL APPROACH

Indications

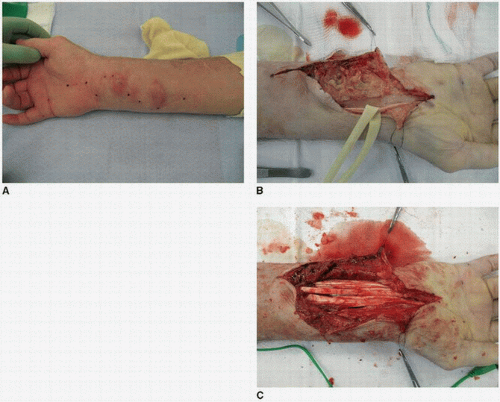

The carpal tunnel may need to be approached for median nerve decompression for isolated carpal tunnel syndrome, for acute carpal tunnel syndrome, or in conjunction with fasciotomy for compartment syndrome. The carpal tunnel may also need to be explored in cases of infection or penetrating trauma, or may need to be opened to identify retracted proximal stumps of finger flexor tendons during repair or reconstruction. The carpal tunnel approach can be extended proximally into the volar approach of Henry to address fractures of the distal radius, as well as permitting access to the volar wrist ligaments, such as in the case of perilunate dislocations. Similarly, tenosynovectomy of the flexor tendons for rheumatoid disease or mycobacterial infection can be performed through this extended approach (Fig. 2-1).

Technique

A variety of approaches for decompression of the median nerve have been described, including one- and two-portal endoscopic, proximal or distal minimally invasive releases, or more traditional open approaches. Regardless of the approach chosen, certain anatomic considerations remain constant.

The carpal tunnel runs from Kaplan’s cardinal line distally to the wrist flexion crease proximally. Just distal to the transverse carpal ligament (TCL) and the carpal tunnel lays the superficial palmar arch, typically 18 mm distal to the distal edge of the ligament (1). The TCL attaches to the scaphoid and trapezium radially and the pisiform and hamate ulnarly.

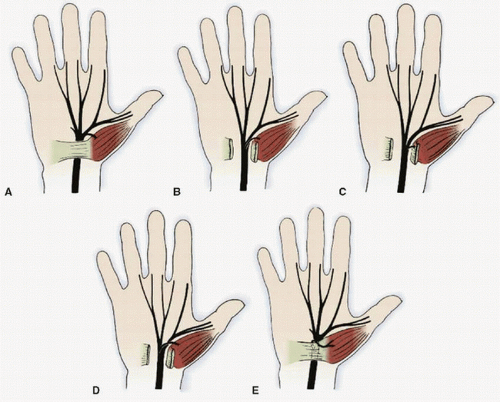

The recurrent motor branch of the median nerve must be protected. Its anatomy is variable. Most commonly, the nerve arises distal to the carpal tunnel, traveling proximally to the thenar muscles. However, approximately 30% of the time, the nerve branches within the carpal tunnel, and then travels in the tunnel until just distal to the TCL, where the recurrent branch turns superficially and radially back into the thenar muscles. Alternatively, approximately 20% of the time, the recurrent branch comes off the median nerve within the carpal tunnel and pierces through the TCL into the thenar musculature (transligamentous). More rare variations include the recurrent branch arising from the ulnar side of the median nerve, multiple motor branches, or division of the median nerve proximal to the carpal tunnel, with the motor nerve then following any of the paths described above to reach the thenar musculature (Fig. 2-2).

Because of this high degree of variance, care must be taken when dividing the TCL to mitigate the potential for iatrogenic injury to the motor branch. By approaching the TCL at its ulnar border, greater distance from the recurrent branch is maintained, protecting the nerve. Should the physician encounter a substantially large palmaris brevis or hypertrophic muscle atop the TCL (2,3) or an aberrant accessory flexor pollicis brevis muscle (4), greater care should be taken, as these are associated with a higher incidence of nontraditional course of the motor branch.

The palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve branches from the median nerve approximately 5 to 6 cm proximal to the wrist flexion crease. It then travels with the median nerve for an additional 2 to 3 cm before running along the ulnar aspect of the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendon. At the flexor retinaculum, it travels between the two layers of the retinaculum, ultimately dividing into three branches, providing sensation to the palm overlying the thenar musculature. By staying ulnar and taking care to divide the antebrachial fascia under direct vision, injury to this branch can be avoided.

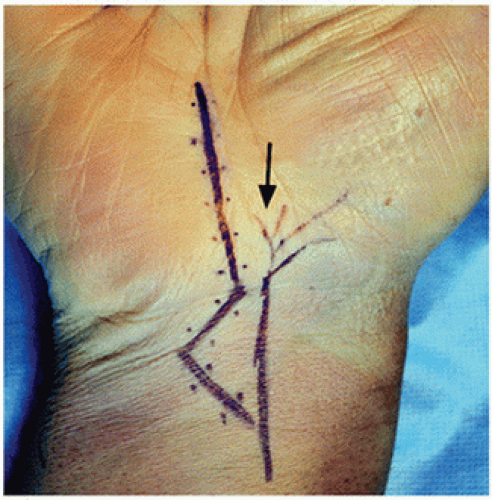

In an open approach to the carpal tunnel, a longitudinal incision along the radial border of the ring finger, starting at Kaplan’s cardinal line (a line extended from the ulnar border of the radially abducted thumb), and extending toward the wrist flexion crease just ulnar to the palmaris longus tendon is made. If no proximal extension of the approach is required, the incision should end distal to the wrist flexion crease, as there is some suggestion of increased pain with more proximal incisions. Should the need to cross the wrist flexion crease exist (such as in cases of tenosynovectomy or extensile approaches for trauma), the incision should cross the flexion crease at an oblique angle, taking care to veer ulnarly to avoid injury to the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve (Fig. 2-3).

Immediately below the skin, there exists a layer of subcutaneous fat. This can be elevated as a pedicled flap based on branches the ulnar artery (hypothenar fat flap) to alter the perineural environment in cases of revision carpal tunnel release (CTR) where significant scarring of the median nerve to the TCL is present. Otherwise, this layer can be divided without consequence.

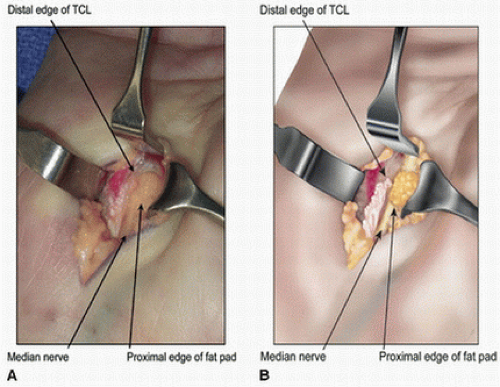

Dissection is carried down to the palmar fascia, which is identified and divided in line with its fibers. The TCL is then visualized. If thenar musculature is encountered on the ligament, the ulnar aspect of its fascia is incised, and the muscle fibers are bluntly swept from ulnar to radial to expose the ligament. Should pockets of fat be encountered, this should alert the surgeon to carefully dissect these areas, as this is often the sign of nearby neurovascular structures, including the recurrent motor branch. Once the ligament is exposed, it is divided along its ulnar aspect. At the distal end, bright yellow fat is encountered, denoting that dissection has been carried far enough distally, and once again alerting the surgeon to the nearby location of the palmar arch (Fig. 2-4).

To expose the proximal ligament and antebrachial fascia, dissecting scissors are used to bluntly open a pocket above the ligament, and a Ragnall or House retractor is placed into the pocket to elevate the skin and palmar fascia away from the TCL and antebrachial fascia. By allowing the wrist to extend, the structures to be divided fall dorsally from the more superficial structures, and can then be released under direct vision with a no. 15 blade. During this portion of the case, the surgeon should either move to the end of or move to the other side of the hand table to allow unrestricted visualization and a more controlled release using one’s dominant hand.

Tips and Pearls

In my practice, for isolated CTR, I typically utilize Bier block (intravenous regional anesthesia) with or without sedation, according to patient preference. Rarely do I have patients who are not willing or able to tolerate this, and general anesthesia is used. I prefer this to local anesthesia, which can blur tissue planes and obscure small nerve branches, which can provide difficulties for the surgeon and when working with trainees. I use a single-forearm tourniquet with 20 to 25 mL of 0.5% lidocaine; forearm tourniquets are well tolerated for these short procedures, and the dose of lidocaine is minimized, allowing the tourniquet to be safely deflated sooner than when larger volumes are used. Because of the short tourniquet duration, a double tourniquet is not necessary. Tourniquet pressure is set at least 100 mm Hg higher than systolic pressure; at least 250 mm Hg, but possibly higher depending on the patient’s blood pressure in the operating room. It is critical to set tourniquet pressure high enough to avoid a venous tourniquet, which significantly complicates the surgery and makes visualization difficult, as the tourniquet cannot be deflated for at least 20 minutes after lidocaine injection in order to prevent systemic side effects of the lidocaine. By initiating the block prior to prepping and draping, the anesthetic has typically had enough time to take effect prior to initiating the surgical portion of the case; by the time that the dressings are applied, the tourniquet has been inflated for 20 minutes and can be safely deflated without fear of systemic side effects from the lidocaine.

In cases of distal radius fracture requiring CTR, I prefer using two separate approaches—one for the distal radius fixation and a separate CTR rather than one extended incision. Decompression of the carpal tunnel has also been described by releasing the radial insertion of the TCL at the distal aspect of the approach for open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of a distal radius fracture (5,6).