Chapter 11 Paediatric Proximal Radial Fractures

Introduction

Since radial head fractures are very rare in children1 this chapter will concentrate on paediatric fractures of the radial neck and their management.

Radial neck fractures account for 1% of all fractures and 5–14% of elbow fractures. They involve all age groups from childhood to prepuberty, with a peak incidence at around 9–10 years of age. They occur at a younger age in girls than in boys (approximately 2 years earlier).2

Most often the injury is a Salter–Harris type II, or complete fracture of the neck itself. Some of these fractures are very difficult to treat, with many possible complications, all of which have a significant, deleterious effect on joint function. The degree of initial anatomical disruption, especially if associated with a vascular lesion, has a major effect on outcome. However, the inadequacies of difficult primary treatment are equally responsible. Open reduction with a condyloradial Steinmann pin is usually associated with a high incidence of complications and, whenever possible, closed treatments are preferred by most paediatric orthopaedic surgeons. To avoid open reduction, two closed methods are helpful and will be described: intramedullary pinning as proposed by JP Métaizeau et al,3–8 and percutaneous pinning.9–11 In our experience, open reduction only becomes necessary when the above methods cannot obtain reduction. Even in these circumstances, osteosynthesis may require intramedullary pinning.

Aetiology

The mechanism of injury is usually an indirect force. It results from a fall onto the outstretched hand in which the elbow is extended or slightly flexed and a valgus force is applied to the elbow joint. According to the Jeffery classification, which is based on the mechanism of injury, it is a type I injury.12 The head of the radius is driven against the capitulum. As the radial head is essentially cartilaginous, it is more resistant to trauma, which is why isolated radial head fractures and epiphyseal separations are so rare. Typically, the proximal radial metaphysis cannot withstand the sudden axial compression forces to which it is subjected, and breaks. Radial neck fractures may also occur in association with dislocation of the elbow: Jeffery type II injury.13 If this occurs during a posterior dislocation of the elbow the radial head remains in an anterior position.14 If, however, it occurs during reduction of the dislocation the radial head will remain posteriorly dislocated (posterior to the capitulum). This form of fracture adversely affects the prognosis because there is an associated vascular risk and because reduction of the fracture is significantly more challenging.

Associated injuries are frequent, from fracture of the olecranon that occurs in an extended elbow, to dislocation of the elbow joint with or without avulsion of the medial epicondyle in an elbow that is slightly flexed on impact.15,16 Skin lesions and neurovascular injuries are, however, rare.

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

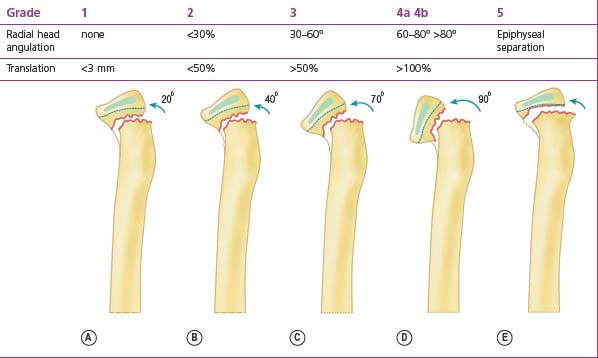

The child usually presents having fallen onto the outstretched hand. The injury most frequently occurs during sport, play or after a simple fall. Clinical examination reveals a swollen elbow that must be carefully evaluated. In addition to assessing the bony anatomy of the joint it is also essential to examine the neurovascular status of the forearm and hand. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the elbow should routinely be undertaken, the fracture configuration studied and displacement of the radial head measured. Accurate classification of the injury enables appropriate treatment to be instituted. Although many radial neck fracture classifications have been developed,1,12,17 that described by Métaizeau et al4 is perhaps the most useful. This classifies radial neck fractures based on translation and is useful because of its influence on prognosis (Table 11.1):4

In 30–50% of severe displaced radial neck fractures another fracture of the elbow joint will have occurred. Most often there is a fracture of the olecranon, lateral condyle, medial epicondyle or ulna, all of which may require an additional procedure with appropriate osteosynthesis.16

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

Conservative treatment

A question that is frequently asked is: allowing for the remodelling capacity of the proximal radial epiphysis, what amount of residual tilting can be accepted in order to permit good results? According to the literature, a residual displacement of 30°, and sometimes 50°,18 is well tolerated and can correct itself spontaneously. This value must be correlated to the age of the child, since a minimum of 3–4 years of growth is required to achieve adequate remodelling. A tilt of 30° is therefore often acceptable in children.

Surgical treatment

Percutaneous pinning

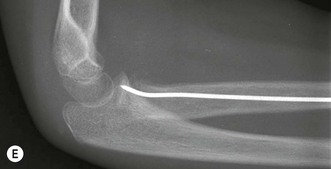

A small stab wound is made on the lateral side of the elbow, 2–5 cm below the level of the radial fracture, depending on the amount of displacement. The more displaced the fracture, the lower the entrance of the wire. This approach must be posterior to the extensor radial muscles and with the forearm in pronation so that the deep branch of the radial nerve is protected by being displaced anteriorly. A smooth 2 or 2.5 mm K-wire is inserted through the wound, the subcutaneous tissues and the muscles to reach the radial head and neck (Fig. 11.1).

Although Lenggenhager originally left the pin in place in the cast, it is nowadays considered unnecessary as sufficient stability can be obtained with a long-arm cast with the elbow flexed at 90° and the forearm in neutral rotation for 3–6 weeks.19 The period of immobilization is determined by the age of the child and is shorter for younger children, whose fractures heal more rapidly.9

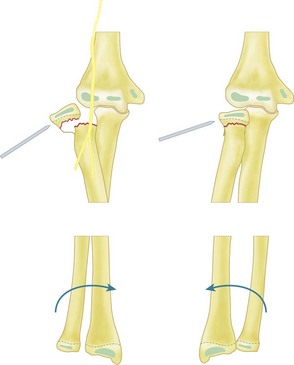

Elastic stable intramedullary nailing (ESIN) technique

Published by Métaizeau et al in 1980,3 this method is very simple but requires perfect knowledge of the elastic stable intramedullary nailing technique, which is used in fractures of the forearm.20

Closed reduction

An alternative reduction manoeuvre involves replacing the thumb with a punch as described above.

Surgical procedure: retrograde radial intramedullary nailing

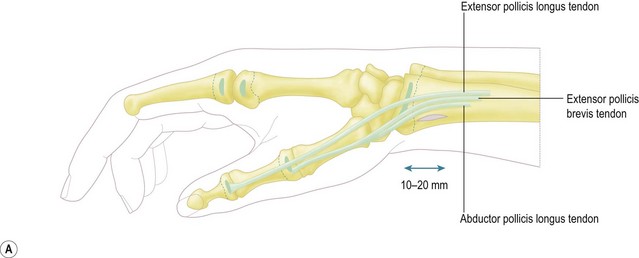

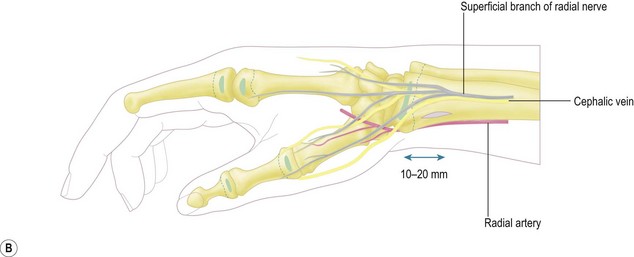

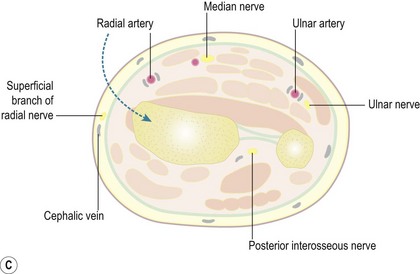

Identification of the distal physis with fluoroscopy assists in accurately positioning the 1.5–2 cm longitudinal incision. Blunt dissection using scissors is then performed. The radial vein and the sensory branch of the radial nerve are successively retracted posteriorly and protected with a mini retractor. Dissection continues anterior to the insertion of the brachioradialis tendon to avoid potential damage to the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus tendons, and is carried down to the bone (Fig. 11.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree