Abstract

Context

Traditional treatment of sacrum osteoporotic fractures is mainly based on antalgics and rest in bed. But complications are frequent, cutaneous, respiratory, thrombotic or digestive and mortality at 1 year significant.

The aims

We wanted to define the interest of sacroplasty when treating osteoporotic fracture of sacrum.

Method

We reviewed literature while studying a clinical case in an elderly patient.

Results

Sacroplasty was efficient at short and mean delay to control the pain due to osteoporotic sacrum fracture. Rate of complications is low in the centers mastering the procedure.

Conclusion

Sacroplasty is of evident interest for elderly patients suffering of an osteoporotic fracture of sacrum. It reduces decubitus complications, secondary effects of antalgics and allows an early reeducation.

Résumé

Contexte

Le traitement traditionnel des fractures ostéoporotiques du sacrum est basé sur le repos au lit et les antalgiques. Cependant, les complications cutanées, respiratoires, thrombotiques et digestives sont fréquentes et la mortalité à un an significative.

Objectif

Définir l’intérêt de la sacroplastie dans le traitement de la fracture ostéoporotique du sacrum.

Méthode

Revue de la littérature à partir d’un cas clinique illustré chez un sujet âgé.

Résultats

La sacroplastie est efficace à court et moyen terme pour contrôler les douleurs en relation avec la fracture ostéoporotique du sacrum. Le taux de complications est faible dans des centres entraînés à la réalisation de la procédure.

Conclusion

L’intérêt de la sacroplastie est évident pour les patients âgés souffrant de fracture ostéoporotique du sacrum car la technique permet de réduire la fréquence des complications de décubitus, les effets secondaires des antalgiques et autorise une prise en charge rapide en rééducation.

1

English version

Osteoporotic fractures of sacrum occur spontaneously or after a fall in elderly patients. Osteoporosis and osteomalacia are the main favouring factors. Diagnosis is often late, or sometimes is not even made. Lumbalgia, pain of the lower limbs, functional disability, seem due to a narrowed lumbar canal, a disc-nervous root conflict or a vertebral fracture. Standard X-rays of lumbar spine show ordinary degenerative lesions and seem sufficient to explain the pain. Pelvic X-rays cannot make the diagnosis. Fractures are discreet, without displacement, often hidden by gas, stercoral stasis or vascular calcifications. This may be the reason why Lourie only described these fractures in 1982 . Until recently, traditional treatment of sacrum fractures was still rest in bed and antalgics. But nearly 50% of the patients in hospital had skin or lung problems, digestive complications or thrombosis. Mortality at 1 year reached 14.3%. As for functional prognosis, one out of two patients did not win back his previous autonomy, one on four was institutionalised . Vertebroplasty, percutaneous injection of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) has, these last years, allowed a significant shortening of painful and bed-ridden time in osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Injection of PMMA in sacrum (sacroplasty) was logically tried in sacrum fractures. It was first done in sacrum metastasis, then evaluated in osteoporotic fractures. In our clinical case, we want to describe precisely to specialists in physical medicine this sure and non invasive technique hoping to reduce the time of bed-confinement and the rate of decubitus complications with long-lasting results on pain.

1.1

Clinical case

A 83 years old man, living in a retirement home, self sufficient, is rushed to hospital in emergency for lumbar and buttock acute pain. Functional disability prevents walking or even standing up.

Pain began a week before without any triggering factor and grew progressively worse. As he entered hospital, the patient could not turn over alone in his bed. Palpation of loins and buttocks aroused acute pain, bilateral but predominantly right.

There is a right clinostatic syndrome but no signs of Lasègue or Léri, no motor or sphincterian defect.

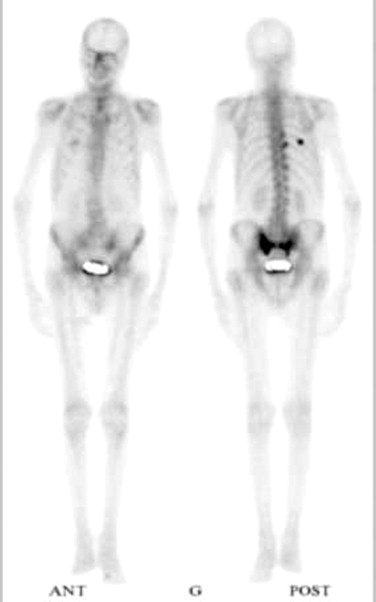

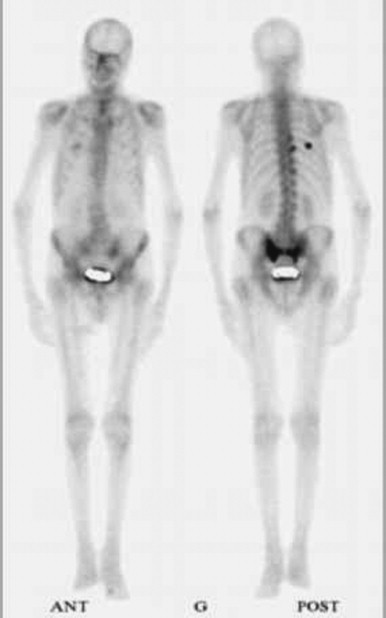

Pelvic X-ray is normal except for a vertebral fracture of L2. Scintigraphy shows a “H” hyperfixation, likely sign of a sacrum bilateral fracture ( Fig. 1 ). Pelvic scanner confirms the diagnosis and shows a bilateral sacrum fracture with right cortical rupture but without tissue infiltration ( Fig. 2 ).

Biological check-up is normal, there is no inflammatory syndrome, calcemia and phosphoremia are normal. There is no abnormal peak on serum proteins electrophoresis. But alkaline phosphatases are a little high (140 UI, N < 105). The 25-OH D3 plasmatic vitamin is low (7.7 ng/ml, N: 16–28ng/ml), parathormone reaches the higher level of normal values (67 pg, N < 65).

Our conclusion is: fracture of sacrum on probable osteomalacia in an elderly man living in institution.

After 10 days of medical treatment, the patient still suffers at any attempt of mobilisation, does not tolerate well antalgics of level II, has frequent spells of confusion, specially at night. So we decide a bilateral sacroplasty.

On the scanner table, the patient is in ventral decubitus, two bone trepans are inserted after premedication at each fracture level ( Fig. 3 ). PMMA is injected in each fracture ( Fig. 4 ) and the result controlled by centered tomodensitometries ( Fig. 5 ). No complication being detected during 30 minutes, he is taken back to his room for a 24 hours rest.

He is, next day, progressively reverticalised and kinesitherapy allows him to walk without suffering. He will on the following day go back to the retirement home with a prescription of calcium and D vitamin.

Forty-eight hours after he has left the service, auxiliaries from the retirement home, phone to tell he walks without any human or technique help and gets down alone to the refectory where he takes his meals.

1.2

Discussion

1.2.1

Clinical signs of sacrum fractures

Osteoporotic fracture symptoms are sudden, with or without a notion of trauma, and get progressively worse.

Risk factors are: female sex, known osteoporosis or past history of osteoporotic fracture, general corticoids, chronic inflammatory rheumatism (ankylosing spondylarthritis), history of pelvic radiotherapy.

Pain is sacrolumbar or pelvic with a marked functional impotence quickly reducing the patient’s usual autonomy. Most frequent irradiations are buttocks and posterior face of the thighs. Inguinal pain must call to mind an association with a pubic fracture. Pain is usually worse when changing position or standing up and somewhat less important when lying down. Clinical examination may show pain when the pelvis is laterally pressed. Faber’s manoeuvre asks the patient to put his heel on his knee on the non-painful side. Then the examinator pushes the homolateral thigh in abduction towards the plan of the table until he wakes up the sacrum pain. Lasègue’s manoeuvre is usually negative. Neurologic examination is usually normal but may reveal sphincter problems or paresthesia of the lower limbs.

1.2.2

Additional exams in sacrum fractures

1.2.2.1

Standard X-rays

May show fracture signs such as a condensation band, a cortical rupture or even fracture lines on the frontal X rays. Diagnosis is seldom done at this stage of exploration. Superpositions and artefacts most usually prevent a good visualisation of the sacrum. But pelvic fractures often associated are nearly always seen.

1.2.2.2

Bone scintigraphy

Is a sensitive exam when looking for a sacrum fracture. The classic “H” picture of a sacrum hyperfixation reflects the three fractures of both sacrum wings and sacrum. However it is only found in 40% of cases . Hyperfixation may also be strictly unilateral with pelvic hyperfixation, or even one or several vertebral hyperfixations.

1.2.2.3

Tomodensitometry

Is the best exam to assert a sacrum fracture only suspected on scintigraphy. It will also eliminate other aetiologies of fractures such as neoplasic tissue infiltration. Tomodensitometries are difficult to read, must often be looked over twice . Radiologic signs change all along the evolution, fracture lines with or without displacement will succeed to sclerosis or a mixture of both.

1.2.2.4

Magnetic nuclear resonance imagery (MRI)

MRI shows bone signals changing with medullar oedema, T1 hyposignal raising in T2. Fracture line itself is not always well seen among changing medullar signals, images are not very specific and may even be misleading especially in a neoplasic known context. The diagnosis of sacrum fracture is not then often looked for, so first intention MRI requires all the radiologist’s attention looking for any modified sacrum signal, especially on parasagittal sections.

1.3

General treatment of sacrum fractures

1.3.1

Conservative treatment

Of sacrum fractures has long been the rule, rest in bed, antalgics, then progressive remobilisation. Treatment by calcium, D vitamin, anti-osteoporotic drugs hoping to reduce the risk of new fractures. Knowing the age of patients, the frequent other morbidities, the risk of decubitus complications increasing demineralisation and muscle atrophy, early reverticalisation is essential . Stimulation of bone formation by gravity and muscle constraints when standing up or exercising has been demonstrated . Rapid reverticalisation fights osteoclastic resorption early seen in immobilisation . But pain may strongly delay reverticalisation of suffering patients, polymedicated, with a poor tolerance for antalgics of II or III levels. Sacroplasty is an interesting technique as it shortens painful time, shortens the bed-ridden time, and allows a quick readaptation of patient.

1.3.2

Sacroplasty

1.3.2.1

Technique

The patient is premedicated 1 hour before the procedure with 1 g of intramuscular pethidine, then receives a perfusion of paracetamol chlorhydrate (2 g) and 5 mg of midazolam per os. He is examined in ventral decubitus usually on a radioscopic table.

After an oblique view bringing in perfect alignment the sacroiliac articulations, two 13 gauges bone trocarts are positioned between the foramen and the sacroiliac articulation, on the fracture side, at 45° with sacroiliac articulation . Needles are then inserted approximately halfway in the sacrum with lateral radioscopic control, and always at a 45° angle. Cement is mixed, 2 to 5 ml are injected in each trocart with an anteroposterior radioscopic control. Progress of the cement is very carefully followed not to have any diffusion towards the sacral roots. Some teams achieve the procedure with tomodensitometric control, others with a double control, tomodensitometric and radioscopic. After the procedure, the patient is kept in ventral decubitus for 30 to 45 minutes.

1.3.2.2

Specific complications

Cement may leak in presacral space, spine canal, sacral foramen, sacroiliac articulation. The most frequent complication is the foraminal leakage in a sacral hole. Radiculalgies can be minimised by infiltration of corticoids and local anaesthetics. They may express the thermic toxicity of PMMA on sacral roots as it polymerises. That is why sacroplasty could perhaps only be done when dealing with fractures of zone I (sacrum wings exterior to foramen). New liquid phosphocalcic bone substitutes, bio degradable could perhaps soon make up for this drawback .

1.3.2.3

Indications

As for vertebroplasty, sacroplasty is thought of when medical treatment has failed in an elderly patient, when the risks of a long decubitus seem higher than those of the procedure. Hyperalgia, intolerance of antalgics, persistence of pain after 15 days of rest in bed are also good indications.

1.3.2.4

Contra-indications

Coagulation defect, infection, incapacity to sustain 10 minutes of ventral decubitus, and, usually, fracture trait near foramen or spine canal.

1.3.3

Efficacy: review of literature

Sacroplasty was initially introduced to treat sacral metastasis by Dehdasti et al. and, independently, Marcy et al. . They reported good results in this indication, respectively one and four cases in oncology. Pommersheim et al. , described three sacrum osteoporotic fractures immediately better after sacroplasty. Amelioration was keeping on at 14 and 16 weeks for two of these three patients. Butler et al. reported six cases of fractures, four obviously linked to osteoporosis. Amelioration was going on for five of the six patients 2 weeks after the procedure. Brook et al. briefly described two post-traumatic osteoporotic fractures of sacrum treated by sacroplasty under tomodensitometric control with good immediate results but no longer follow-up. Masala et al. had an original way of treating a 61-year old patient with metastases of sacrum and iliac wings. They injected cement under fluoroscopic control after introduction in the bone lesions of Kirschner threads and tomodensitometric control. Layton et al. treated by sacroplasty an 86 years old woman with a post-traumatic sacrum fracture, still suffering under morphine. As she had other pelvic fractures, she was only partially relieved but morphine could be replaced by oxycodone and she could walk the day after the procedure. Binaghi et al. treated a 68 years old woman with important sacrum pain after falling and no reply to medical treatment for 4 weeks. Immediately after sarcoplasty, pain decreased by 80%, antalgics were totally stopped after a week, the patient went back home with total autonomy. The first important series of sacrum fractures treated by sacroplasty was published by Frey et al. . In their work, 37 patients, 27 of them women, were included. Mean age was 76, mean time of evolution before procedure was 34 days. Initial pain score (on analogic visual scale) was 77 mm, then 32 mm at 30 minutes, 21 mm at 2 weeks, 13 mm at 12 weeks, and 7 mm at 52 weeks. They only had one complication, a sciatalgia disappearing after cortisone infiltration. Heron et al. treated three patients who had been suffering for a mean time of 8 months with a 80 mm score on analogic visual scale. After the procedure, mean pain score was 20 mm. One patient had an asymptomatic cement leak in the first sacral hole. Strub et al. treated 13 women of mean age 76. Eighty-four percent had a bilateral sacroplasty. After a mean time of 15 months, 83% were asymptomatic. Most of these studies, though having no control group, already encourage to apply the technique first used for as a vertebroplasty to important sacrum fractures resisting medical treatment.

1.4

Conclusion

Osteoporotic fracture of sacrum has for a few years been treated by injection of PMMA. This technique first used in vertebroplasty gives good results at short and mean time with few complications but must be realised in a specialised centre. Randomized and controlled studies still remain necessary to determine the interest of the technique when compared to the spontaneous evolution with simple medical treatment. If efficacy of sacroplasty is confirmed, interest for the patient will be obvious: less decubitus complications, less secondary effects of antalgics, less demineralisation and amyotrophy and earlier secondary prevention of osteoporosis.

2

Version française

Les fractures ostéoporotiques du sacrum surviennent spontanément ou à la suite d’une chute chez des sujets âgés. L’ostéoporose et l’ostéoporomalacie en sont les principaux facteurs favorisants. Le diagnostic est souvent retardé ou non fait car les lombalgies, les douleurs des membres inférieurs et l’impotence fonctionnelle sont souvent mises sur le compte d’un canal lombaire rétréci, d’un conflit discoradiculaire ou d’une fracture vertébrale. Les radiographies standard du rachis lombaire montrent des remaniements dégénératifs banals mais souvent incriminés dans la genèse des douleurs. La radio du bassin ne permet pas le diagnostic car les fractures sont discrètes, non déplacées et souvent masquées par des gaz, de la stase stercorale ou des calcifications vasculaires. Cela explique la description tardive qui en a été faite de ces fractures par Lourie en 1982 .

Jusqu’à présent, le traitement traditionnel des fractures du sacrum était basé sur le repos au lit et les antalgiques. Cependant les complications cutanées, respiratoires, thrombotiques et digestives intéressent près de 50 % des patients hospitalisés et la mortalité à un an est de 14,3 %. Le pronostic fonctionnel est engagé chez un patient sur deux qui ne retrouvera pas son autonomie antérieure et chez un patient sur quatre qui devra être institutionnalisé .

L’injection percutanée de polyméthylméthacrylate (PMMA) vertébrale (vertébroplastie) a permis, ces dernières années, de raccourcir significativement la durée de la phase douloureuse et la période d’alitement dans les fractures vertébrales ostéoporotiques. L’injection de PMMA dans les fractures du sacrum (sacroplastie) en est le prolongement logique. La sacroplastie a été initialement proposée dans les métastases sacrées avant d’être évaluée dans les fractures ostéoporotiques du sacrum. Nous présentons, à partir d’un cas clinique illustré, au spécialiste de médecine physique, une technique peu invasive, sûre, permettant de réduire la durée de la phase d’alitement et les complications de décubitus et dont les résultats sur la douleur sont maintenus dans le temps.

2.1

Cas clinique

Un homme de 83 ans, autonome, vivant en maison de retraite, est hospitalisé en urgence pour douleurs lombaires et fessières de survenue brutale avec impotence fonctionnelle empêchant la station debout et la marche.

Les douleurs ont commencé une semaine avant l’hospitalisation, sans facteur déclenchant, avec une aggravation progressive. À l’examen d’entrée, le patient ne peut se tourner seul sur le plan du lit. La palpation de la région lombofessière réveille une douleur intense de façon bilatérale mais prédominant à droite. Il existe un syndrome clinostatique droit mais pas de signe de Lasègue ou de Léri, pas de déficit moteur ou sphinctérien.

La radiographie du bassin est normale mais il existe une fracture vertébrale de L2 sur le cliché du rachis lombaire. La scintigraphie osseuse met en évidence une hyperfixation en H témoignant d’une probable fracture bilatérale du sacrum ( Fig 1 ). Le scanner du bassin confirme le diagnostic en montrant une fracture sacrée bilatérale avec une rupture de corticale à droite mais sans infiltrat tissulaire ( Fig 2 ).