Osteoid Osteoma

It is generally accepted that osteoid osteoma is a neoplasm and not the result of some obscure infection or other known specific etiologic agent. This distinctive benign osteoblastic lesion consists of a small oval or round mass commonly called a nidus. The nidus is often associated with a surrounding zone of sclerotic bone, especially when the lesion develops in a cortical portion of bone. The nidus is the essential part of the tumor; the surrounding sclerosis is a reversible change that disappears after the nidus is removed. The major component of the tumor is a meshwork of osteoid trabeculae of various degrees of mineralization in a background of usually vascular fibrous connective tissue.

In certain instances, focal subacute or chronic osteomyelitis (Brodie abscess) produces a clinical and radiographic pattern that has been confused with that of osteoid osteoma, especially when the inflammatory lesion is associated with a small, discrete, central rarefied focus. Histologically, the lesion produced by inflammation is readily differentiated from an osteoid osteoma when appropriate sections are made. An osteoid osteoma located immediately beneath articular cartilage can be mistaken for osteochondritis dissecans radiographically. Although focal islands of idiopathic medullary sclerosis may be the size of a nidus of sclerotic osteoid osteoma, they do not produce clinical symptoms.

For a neoplasm, osteoid osteoma has a strangely limited growth potential, and tumors more than 1.5 cm in largest dimension are unusual. The tumor may have a remarkable histologic similarity to osteoblastoma, as described in Chapter 10. All lesions less than 1 cm in greatest dimension were arbitrarily called osteoid osteoma by McLeod and coauthors; they called lesions more than 2 cm in diameter osteoblastomas. They used an arbitrary dividing line of 1.5 cm for lesions indistinguishable by all other criteria.

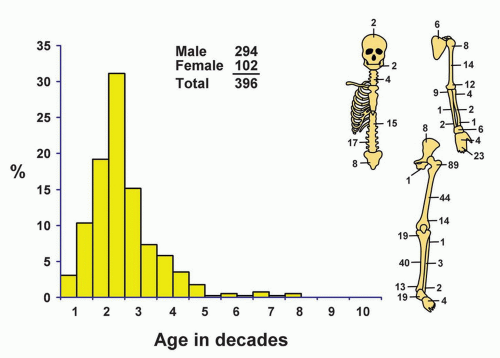

INCIDENCE

The 396 cases of osteoid osteoma in the Mayo Clinic series accounted for 12.9% of all benign tumors (Fig. 9.1). This percentage is probably lower than the actual incidence, because this type of tumor was recognized only rarely before 1940.

SEX

Male predominance was pronounced by a ratio of almost 3:1. Male and female age and localization distributions were similar.

AGE

Approximately 76% of patients in the Mayo Clinic series were 5 to 24 years old. Twelve patients were younger than 5 years; the youngest was 21 months old, and the oldest was 72 years old.

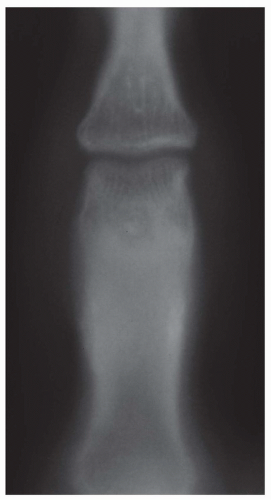

LOCALIZATION

More than half of osteoid osteomas occur in the femur and the tibia. The proximal femur, including the femoral neck, is by far the single most common location. In long bones, the lesion is usually near the end of the shaft or in the middle portion. In vertebrae, the arch is most commonly involved. Some of the vertebral and nonvertebral examples described in the literature are undoubtedly benign osteoblastomas. In the Mayo Clinic series, only two lesions involved the skull, and none involved the clavicle or sternum. The phalanges of the hands were the fifth most common location, but there were no examples in the phalanges of the feet. The tarsal bones, however, were relatively commonly involved. Only one patient had lesions involving more than one bone. This patient had an osteoid osteoma of the distal phalanx of the index finger removed in 1967 and presented with a lesion of the femoral neck in 1981. Two patients had what appeared to be multicentric disease involving one site. Three other patients had questionable multiple niduses in one bone.

SYMPTOMS

By far the most important complaint is pain of gradually progressive severity. The duration of pain before the patient seeks medical care may vary from weeks to several years. Typically, salicylates relieve the pain dramatically. The pain is usually described as being worse at night, interfering with sleep. The pain is often referred to the adjacent joint region and occasionally to a site so distant from the lesion that radiographic studies are misdirected. In a report of 38 patients with bone tumors who had a preoperative diagnosis of lumbar disk syndrome, Sim and coauthors found that osteoid osteoma was the most common bone tumor simulating disk prolapse clinically. In some instances, especially when the involved bone is near the skin, painful local swelling may become evident. Growth disturbances, including increased bone length, may occur. Osteoid osteoma may produce scoliosis and flexion contractures. Tumors located near a joint may simulate arthritis. Kattapuram and coauthors highlighted the delay caused in making the correct diagnosis in these patients because they are treated as if they had arthritis.

Only six lesions in the series were painless. Some lesions of fibrous dysplasia, especially in the ribs and jawbones, may have areas simulating the appearance of osteoid osteoma. Hence, reports of painless osteoid osteomas have to be interpreted with some skepticism. The cause of the very typical pain associated with osteoid osteoma is still not clear. Nerves, identified by special axon stains, within the nidus may be causally related to the pain. High levels of prostaglandins in the lesion have also been implicated and may explain why aspirin relieves the pain.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Dysfunction, often resulting in a limp, is commonly produced by an osteoid osteoma. Atrophy of some of the muscles of the affected extremity is common. When added to the character of the pain and the decreased muscle stretch reflexes, the atrophy may suggest a neurologic disorder. This combination resulted in a clinical suspicion of lumbar disk prolapse in seven patients in the series; three had undergone a laminectomy. One other patient had been operated on for a suspected glomus tumor of soft tissue.

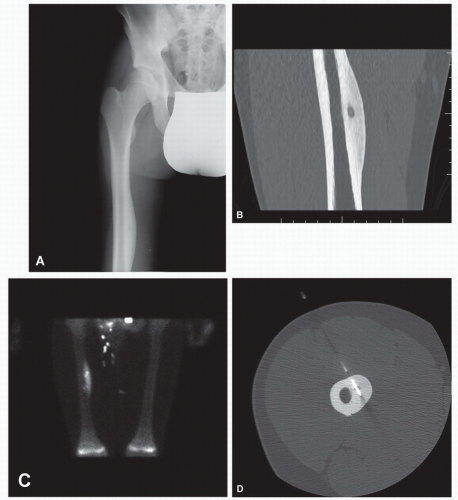

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

Typically, the nidus of an osteoid osteoma appears as a small, relatively radiolucent zone. The nidus may undergo various amounts of sclerosis and, hence, may appear as a rounded area of sclerosis with a halo of lucency around it. A variable, sometimes extensive, sclerotic zone ordinarily surrounds the nidus and may mask it, necessitating special radiographic techniques for its demonstration. In a study of 100 cases of histologically proven osteoid osteoma, Swee and coauthors found that in 75 cases, the plain radiographs were diagnostic of osteoid osteoma. Seventeen patients had equivocal radiographic findings, and 14 of these patients had tomography. Eleven of the tomograms demonstrated a nidus. Eight patients had normal plain radiographs. Seven of them had tomography, and in three, the tomograms showed a nidus. When findings were positive on plain radiographs, tomograms did not add to the preoperative diagnosis, although they tended to help in localizing the lesion (Figs. 9.2, 9.3, 9.4 and 9.5).

The exact localization of a nidus of osteoid osteoma may be difficult because of either the anatomy of the location, such as in the spine, or extensive new bone formation. Osteoid osteoma always tends to give positive results on a bone scan. Although the entire area of sclerosis is positive, the nidus shows a focal area of increased activity. This sign has been suggested to be of help in localizing an osteoid osteoma. Computed tomography is the preferred method for localization of the nidus, especially in the spine.

Sometimes the reactive periosteal laminations of new bone mimic those of Ewing tumor. One patient in the series had been treated with radiation elsewhere because of a mistaken diagnosis made on the basis of the radiographic findings. More often, the periosteal bone formation is thick and benign appearing and may be mistaken for an osteoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree