Osteochondroma (Osteocartilaginous Exostosis)

Osteochondromas arise on the surface of bone and are composed of a cartilage-capped osseous stalk that is continuous with the underlying bone. The majority of osteochondromas occur as solitary lesions. However, approximately 15% of osteochondromas occur in the setting of multiple osteochondromas or hereditary multiple exostoses, an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by multiple osteochondromas. In almost 90% of patients with hereditary multiple exostoses, germline mutations in the tumor-suppressor genes EXT1 or EXT2 are found. In addition, EXT1 has been found to act as a tumor suppressor gene in the cartilage cap of solitary nonhereditary osteochondromas. Growth of osteochondromas usually parallels that of the patient, and the lesion often becomes quiescent when the epiphyses have closed. Spontaneous regression has been described.

Bony spurs that result from trauma or degenerative joint disease may simulate the appearance of osteochondromas but do not belong in the same group.

Some patients with multiple hereditary exostoses also have other developmental abnormalities of bone such as shortening of the ulna and displacement of the radius outward. The fibula also may be shortened. In addition, there is lack of tubulation of the long bones, which may be especially prominent in the femoral neck region. Each tumor in patients with multiple hereditary exostoses has a characteristic that will be described for the solitary form. The exact risk of chondrosarcomatous change in patients with multiple exostoses is unknown because of selection factors related to the indication for surgery in individual patients with benign or suspected malignant tumors and the lack of follow-up from birth to death in a large group of selected patients with multiple osteochondromas (the same drawbacks apply to the calculation of the risk for patients with other benign conditions, such as multiple chondromas). Peterson, after follow-up studies in a number of patients with multiple hereditary exostoses, thought that malignant change occurs in fewer than 1% of patients.

In a study of 75 patients with chondrosarcoma secondary to osteochondroma, Garrison and coauthors found that 27.3% of patients with multiple osteochondromas who underwent surgery had secondary chondrosarcomas, whereas only 3.2% of patients with the solitary form had malignant change. A later study by Ahmed and coauthors found the incidence to be 36.3% and 7.6%, respectively. However, these figures are probably an exaggeration because of selection factors. Patients with secondary malignant lesions are much more likely to seek medical attention. Most patients with multiple exostoses have many, sometimes innumerable, lesions that may be grossly deforming, although an occasional patient has only two or three lesions. One patient in the Mayo Clinic series had polyposis of the colon.

Subungual exostoses are peculiar projections from the distal portion of the terminal phalanx, usually the first toe. They are almost certainly a form of heterotopic ossification. These exostoses are not included in the data on osteochondromas, although they possess some of the radiographic and pathologic features of osteochondroma.

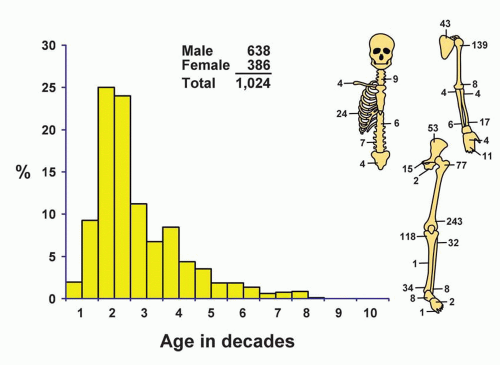

INCIDENCE

Osteochondromas accounted for 33.4% of the benign bone tumors and 10.1% of all tumors in the Mayo Clinic series. Of all tumors in the chondrogenic series, 32.8% were osteochondromas. Most osteochondromas are asymptomatic and are never found, and many of those that are discovered are never excised, so that the actual incidence is much greater than these figures for surgical cases indicate. Approximately 86% of the patients (884) had solitary lesions. One patient with a lesion of the proximal fibula had received radiation treatment for a desmoid tumor previously (Fig. 2.1).

SEX

Approximately 62% of the patients in both the solitary and the multiple exostoses groups were males. The literature indicates little sex predilection.

AGE

At the time of the first excision of the osteochondroma, approximately 60% of the patients were younger than 20 years, and 49% were in the second decade of life. The ages of patients with multiple exostoses closely paralleled the ages of patients with single exostosis.

LOCALIZATION

Osteochondromas may occur on any bone in which enchondral ossification develops. They usually occur in the metaphyseal region of the long bones of the limbs. Rarely, they are near or in the middle of such bones. The lower end of the femur, the upper end of the humerus, and the upper end of the tibia, in that order, were most frequently involved. The ilium contributed 53 of the 70 osteochondromas arising from the innominate bone. Only 26 patients with solitary lesions had involvement of the small bones of the hands and feet. Involvement of the small bones is not uncommon in patients with multiple hereditary exostoses. An osteochondroma-like lesion of a small bone is much more likely to be a reactive process. The bones of the skull and jaw were not involved with osteochondroma.

SYMPTOMS

The patient’s symptoms are generally related to the size of the tumor. The most common complaint is that of a hard swelling, usually of long duration. Pain may result from impingement of the tumor on neighboring structures and from weight-bearing or other activity. Pain or mass effect may be caused by an overlying bursa. An overlying bursa was significant enough to be described in 13 of the cases. The bursa may suggest a soft tissue mass and hence the possibility of a secondary chondrosarcoma. Ultrasound examination has been suggested to be of use in recognizing the bursa. The bursa may contain osteocartilaginous loose bodies or even nodules of synovial chondromatosis. One instance of nodules of chondrosarcoma situated in a bursa overlying a secondary chondrosarcoma and simulating chondromatosis has been described. Pain may also result from a fracture through the stalk of the osteochondroma.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A palpable mass is ordinarily the only finding. Secondary effects may occur, especially when the tumor impinges on the spinal canal.

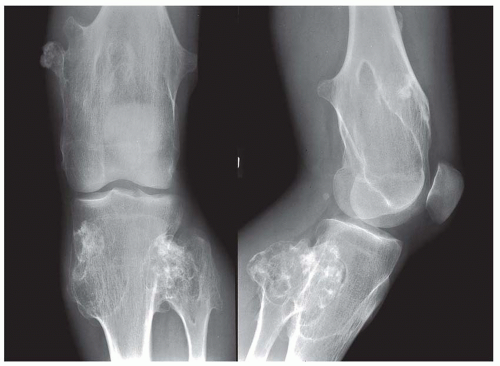

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

The characteristic radiographic appearance is a projection composed of a cortex continuous with that of the underlying bone and spongiosa, similarly continuous. The adjacent cortex often flares to become the base of the tumor. The projection may have a broad base or be distinctly pedunculated. Irregular zones of calcification may be present, especially in the cartilaginous cap, but extensive calcification with radiolucent irregularities of the cap should arouse the suspicion of malignant change. Osteochondroma commonly arises at the site of tendon insertions, and the direction of growth is often along the line of the tendon’s pull. Pedunculated osteochondromas characteristically point away from the nearest joint. The affected bone is often abnormally wide at the level of an osteochondroma because of failure of normal tubulation. Such widening is especially likely in patients with multiple exostoses. In some instances, computed tomographic images and magnetic resonance images may be useful in demonstrating the continuity between the osteochondroma and the underlying bone, especially in lesions of flat bones. These modern techniques are also helpful in accurately delineating the thickness of the cartilage cap (Figs. 2.2, 2.3, 2.4, 2.5 and 2.6).

GROSS PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

The gross pathologic features confirm the radiographic pattern. Sessile exostoses may be flat, whereas pedunculated ones are somewhat long and slender, and variations between these exist. Many are cauliflower-shaped, with or without a stalk (Fig. 2.7).

The cortex and periosteal covering of the tumor are continuous with those of the underlying bone. A bursa may develop over the exostosis. The marrow of the tumor may be fatty or hematopoietic, often mirroring the status of the spongiosa of the underlying bone with which it merges (Figs. 2.6 & 2.8).

The gross specimen should be cut perpendicular to the bony stalk so that the true thickness of the cartilage cap can be measured. This cap may cover the entire external surface of a sessile tumor, but it covers only the rounded end of a stalked exostosis. The cap is ordinarily 2 to 3 mm thick and has a smooth surface. The cartilage may be 1 cm or more in thickness in the actively growing benign exostosis of adolescents (Fig. 2.7). Irregularity and thickening of the cap, especially in an adult, demands careful histologic study because of the likelihood of secondary chondrosarcoma. Although a rare thinner cap may be associated with malignancy, secondary chondrosarcomas are usually at least 2 cm in thickness. Cystic change within a cartilage cap also is a cause for concern. If the cartilaginous rim is thin and regular and the underlying spongiosa appears to be normal, the tumor is always benign. If the exostosis is arrested, as may occur in adults, there may be practically no cartilaginous cap. This appearance is especially likely with the rare osteochondroma associated with an overlying bursa. The osteochondroma giving rise to the bursa may be tiny and overlooked.

Figure 2.3. Coronal T1-weighted MRI of an osteochondroma involving the left femur. The lesion has a thin cartilage cap. |

Figure 2.5. Multiple hereditary exostoses. The individual osteochondromas have the same appearance as those in patients with solitary exostoses. There is lack of tubulation of the distal femur. |

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|