Chondromyxoid Fibroma

Chondromyxoid fibroma is a rare benign tumor, apparently derived from cartilage-forming connective tissue. Its name, which is cumbersome, has the merit of being highly descriptive and has gained acceptance for this distinctive tumor. The tumor was described originally by Jaffee and Lichtenstein in 1948 when they presented eight cases and emphasized the danger of mistaking this benign neoplasm for a malignant lesion, especially chondrosarcoma. Although chondromyxoid fibroma characteristically contains variable amounts of chondroid, fibromatoid, and myxoid components, certain portions within at least some tumors resemble hyaline cartilage; therefore, it is logical to include this neoplasm among those of cartilaginous predilection. The rationale of this classification is enhanced by the striking histologic similarity sometimes shared by chondromyxoid fibroma and benign chondroblastoma.

Many of the tumors described in the literature as myxomas and fibromyxomas are, no doubt, chondromyxoid fibromas. The distinctive myxoma (fibromyxoma) of a jawbone lacks the lobulation and varied histologic spectrum of chondromyxoid fibroma. It has no exact counterpart in the rest of the skeleton and is apparently of odontogenic derivation.

The earlier admonition to avoid overdiagnosing chondromyxoid fibroma as chondrosarcoma has been taken too seriously by some pathologists. In several instances, errors have been made in the reverse direction, with consequent inadequate treatment of chondrosarcoma.

Chondromyxoid fibromas can be expected to behave in a benign fashion, except for the extremely rare lesion that undergoes malignant transformation spontaneously and the lesion subject to the slight risk of malignant change by radiation therapy.

INCIDENCE

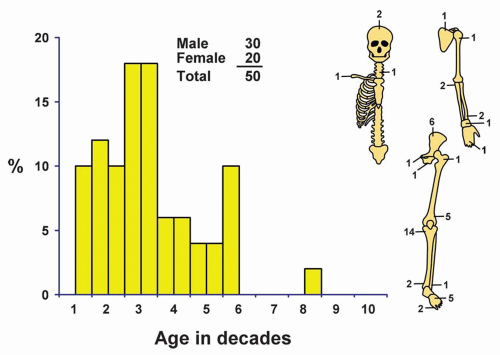

Chondromyxoid fibroma is one of the less common neoplasms of bone, accounting for only 1.6% of all benign neoplasms in the Mayo Clinic files (Fig. 5.1). It accounted for less than 0.5% of all bone tumors. Chondroblastoma is almost three times as common as chondromyxoid fibroma.

SEX

A definite male predilection was found in this series. The literature indicates only a very slight male predominance.

AGE

Chondromyxoid fibroma has a marked predilection for patients in the second and third decades of life. Fifty-eight percent of all patients were in these two decades. The youngest patient was 6 years old and the oldest 75.

LOCALIZATION

Typically, chondromyxoid fibroma is located in the metaphyseal region of a long bone and may abut or be a variable distance from the epiphyseal line. Rarely, the tumor involves both the metaphysis and the epiphysis. This localization suggests that, like benign chondroblastoma, chondromyxoid fibroma may arise from the epiphyseal cartilaginous plate. In a large series reported by Wu and coauthors, the tumor was diaphyseal in 11 cases and epiphyseal in only one. Approximately two-thirds of the recorded examples of this tumor have been in the long tubular bones, with approximately one-third of all tumors occurring in the tibia. The proximal tibial metaphysis was the most common location in the series. The small bones of the foot are also commonly involved. Chondromyxoid fibroma is uncommon in the vertebrae, ribs, scapula, skull, and jawbones.

Ten tumors in the series occurred in patients older than 40 years; three of these tumors involved the long

tubular bones. The seven others involved the pelvic bones, the small bones of the foot, and the nasal septum.

tubular bones. The seven others involved the pelvic bones, the small bones of the foot, and the nasal septum.

SYMPTOMS

Pain is by far the most common presenting symptom in chondromyxoid fibroma. Occasionally, pain is of several years’ duration. Local swelling may be noticed by patients whose tumors are not camouflaged by a thick layer of overlying tissue. Such tumefaction had been noted by only six patients in this series. Swelling was more common in tumors of the small bones. Occasionally, these tumors are asymptomatic incidental findings on radiographs. One patient had radiographic evidence of rickets, which resolved after the lesion was removed. However, although this lesion has been classified as a chondromyxoid fibroma, it has some unusual histologic features.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Physical examination is of little diagnostic aid. Tenderness in the region of the tumor or a tender or nontender mass help in the exact localization.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

Chondromyxoid fibroma characteristically appears as an eccentric, sharply circumscribed zone of rarefaction that occasionally expands the bone. Especially in a small bone, this tumor can produce fusiform expansion of the entire contour of the bone (Figs. 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4).

In most cases, trabeculae appear to traverse the defect, but these are merely the radiographic reflections of corrugations on the surface of the cavity that contains the tumor. The defect may be rounded or oval. Frequently, the lesion has a scalloped appearance similar to that in metaphyseal fibrous defect (Fig. 5.5); this lobulated appearance may be appreciated best on magnetic resonance images. Sometimes there is a thin line of sclerosis in the surrounding bone. Radiographic evidence of calcification is rare in chondromyxoid fibroma. It was reported in only 1 of 76 cases described by Rahimi and coauthors. Pathologic fracture was present in 4 of the 30 cases described by these authors. Although the lesion may destroy the cortex and, especially in small bones, expand into soft tissue, the radiographic features are consistently those of a benign process (Figs. 5.6, 5.7, 5.8 and 5.9).

Robinson and coauthors described 14 examples of chondromyxoid fibroma involving the surface of bone, usually the femur and the tibia. In addition to the unusual location, these lesions tended to show extensive mineralization (Fig. 5.10).

GROSS PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

The average chondromyxoid fibroma is small. In the Mayo Clinic series, the greatest dimension of these tumors was up to 5 cm, although larger tumors have been reported. Grossly, curetted fragments appear firm, somewhat fibrous, and semitranslucent. The lesion rarely resembles hyaline cartilage. If the lesion is removed intact, it appears lobulated and sharply demarcated from the surrounding bone. Although the lesion appears translucent, a frank myxoid quality is not apparent grossly (Figs. 5.11, 5.12 and 5.13).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|