Osteochondral Transfer for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus

Mark E. Easley

Justin Orr

DEFINITION

Medium-sized osteochondral defects of the talar dome

May approach the talar shoulder (transition of superior dome cartilage to the medial or lateral talar cartilage)

Often associated with subchondral cysts

Osteochondral defect is reconstructed with a cylindrical osteochondral graft. To provide stability to this graft, the osteochondral defect in the native talus must be contained (have circumferential cartilage and subchondral bone).

ANATOMY

Sixty percent of the talus’ surface area is covered by articular cartilage.

The talus is contained within the ankle mortise.

Superior talar dome articulates with the tibial plafond.

Medial dome articulates with the medial malleolus.

Lateral dome articulates with the lateral malleolus.

Talar blood supply

Posterior tibial artery

Artery of the tarsal canal

Deltoid ligament branch

Peroneal artery

Artery of the tarsal sinus

Dorsalis pedis artery

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis for osteochondral lesions of the talus (OLTs) is not fully understood.

Theories include the following:

Trauma

Idiopathic focal avascular necrosis

NATURAL HISTORY

In general, OLTs do not progress to diffuse ankle arthritis.

However, large volume OLTs may lead to subchondral collapse of a substantial portion of the talus and thus create deformity, higher contact stresses, and a greater concern for eventual ankle arthritis if left untreated.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients may or may not report a history of trauma.

Ankle pain, typically on the anterior aspect of the ankle, is a common complaint.

Pain is usually experienced on the side of the ankle that corresponds with the OLT, but it may be poorly localized to the site of the OLT. In fact, sometimes, medial OLTs produce lateral ankle pain and vice versa.

Pain is rarely sharp, unless a fragment of the OLT should act as an impinging loose body in the joint.

Typically, the pain is a deep ache, with and after activity, and is usually relieved with rest.

Antalgic gait

May be associated with malalignment or ankle instability

Typically, tenderness on side of ankle that corresponds with OLT but not always

Rarely crepitance or mechanical symptoms

With chronic OLT, some degree of ankle stiffness is anticipated.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs

Obtain weight bearing, three views of the ankle

Small OLTs may be missed.

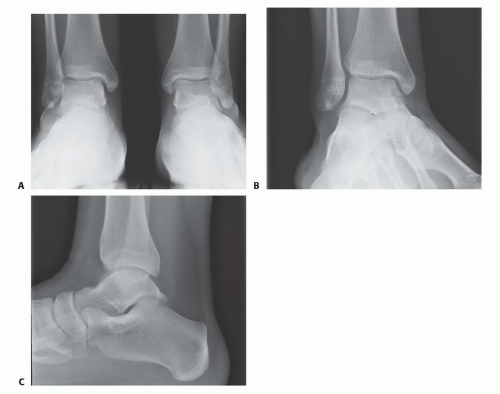

Large OLTs are usually identified on plain radiographs (FIG 1).

Often limited in characterizing OLT because the twodimensional study cannot define the three-dimensional OLT

Particularly useful in assessing lower leg, ankle, or foot malalignment that needs to be considered in the management of OLTs

May detect incidental OLTs (patient has a radiograph for a different problem and an OLT is incidentally identified on plain radiographs)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Excellent screening tool when OLT or other foot-ankle pathology is suspected

Will identify incidental OLT but defines other potential soft tissue pathology

Demonstrates associated marrow edema that may lead to overestimation of the OLT’s size

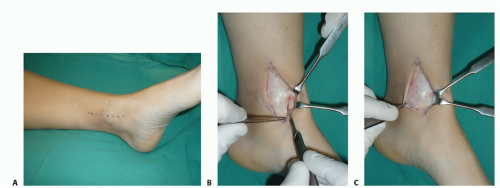

Computed tomography (CT) (FIG 2)

Ideal for characterizing OLT, particularly large volume defects

Defines OLT size without distraction of associated marrow edema

Defines the character of the OLT and extent of its involvement in the talar dome

Diagnostic injection

Intra-articular

An anesthetic versus anesthetic plus corticosteroid

May have some therapeutic effect, even for several months

If the source of pain is the OLT, then intra-articular injection should relieve symptoms from OLT. If the pain is not relieved, then other diagnoses should be considered.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Loose body in ankle joint

Ankle impingement (anterior or posterior)

Chronic ankle instability (medial, lateral, or syndesmotic)

Ankle synovitis or adjacent tendinopathy

Early ankle degenerative change

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Activity modification

Bracing

Physical therapy if associated ankle instability

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories or COX-2 inhibitors

Corticosteroid injection

Viscosupplementation

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Indications for this surgery include the following:

Medium-sized OLTs not amenable to other joint-sparing procedures. If associated with a large subchondral cyst, then arthroscopic débridement and microfracture may not be effective, and some surgeons recommend osteochondral transfer as a primary procedure.

FIG 2 • CT. A. Coronal view with medial OLT that approaches talar shoulder but appears contained. B. Sagittal view demonstrating rather medial OLT. C. Axial view with posteromedial OLT.

Failed arthroscopic (débridement and microfracture) management

Potential sites for graft harvest

Patient’s ipsilateral knee (superolateral femoral condyle, intracondylar notch)

Allograft talus

Ipsilateral knee versus talar allograft

Knee is autograft; however, knee cartilage is thicker than ankle cartilage and may have different biomechanical properties.

Allograft talus offers nearly the same cartilage thickness and harvest from the exact location of the native talus defect; however, it is not the patient’s own tissue.

The surgeon should check for associated pathology that may need to be addressed at the time of allograft talar reconstruction:

Osteophyte removal

Ligament reconstruction

Corrective osteotomies (calcaneal, supramalleolar)

Patient education

This is a complex procedure.

The patient must understand that the intent is to transfer cartilage and bone from one location to another and expect it to incorporate into the native talus.

If allograft is used, there is a negligible but real risk of disease transmission and possible graft rejection by the host.

There is no guarantee that the procedure will work, and a revision procedure may be required, such as structural allograft reconstruction or potentially ankle arthrodesis.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine (FIG 3).

For a lateral OLT, a bolster under the ipsilateral hip typically affords better access to the lateral talar dome.

We routinely use a thigh tourniquet.

Approach

The surgeon must determine the optimal surgical approach:

Medial talar dome (usually centromedial or posteromedial) typically warrants a medial malleolar osteotomy.

FIG 3 • Positioning is supine, with easy access to the medial ankle but without too much external rotation, which would make access to the lateral knee cumbersome.

Lateral talar dome (often centrolateral) typically necessitates ligament releases (anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular) with or without lateral malleolar osteotomy.

The key is that exposure must allow perpendicular access to the OLT; otherwise, the dedicated instrumentation for the osteochondral transfer cannot be used.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Medial Approach for a Medial Osteochondral Lesion of the Talus

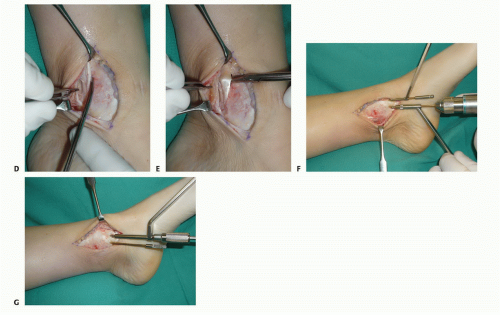

Make a longitudinal incision centered over the medial malleolus (TECH FIG 1A).

Anterior ankle arthrotomy

Identify the joint line (TECH FIG 1B).

Visualize the anterior talus and possibly anterior OLT (TECH FIG 1C).

Open the flexor retinaculum (TECH FIG 1D).

Identify and protect the posterior tibial tendon (PTT) (TECH FIG 1E).

Predrill the intended screw holes for fixation of the osteotomy.

Two parallel drill holes in the same orientation are typically used for open reduction and internal fixation of a medial malleolar fracture (TECH FIG 1F).

Consider tapping the screw holes as well (traditional malleolar screws are not self-tapping) (TECH FIG 1G).

Trajectory of the oblique osteotomy

Should target tibial plafond at lateral extent of OLT

Allows perpendicular access to the OLT with the dedicated instrumentation

We routinely use a Kirschner wire to determine the trajectory for the osteotomy.

Place the wire slightly proximal and lateral to the planned osteotomy so as not to interfere with the saw blade and chisel (TECH FIG 2A).

Confirm desired Kirschner wire trajectory with fluoroscopy.

Mark the osteotomy.

Across the periosteum and with minimal periosteal stripping (TECH FIG 2B)

Perpendicular to the tibial shaft axis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree