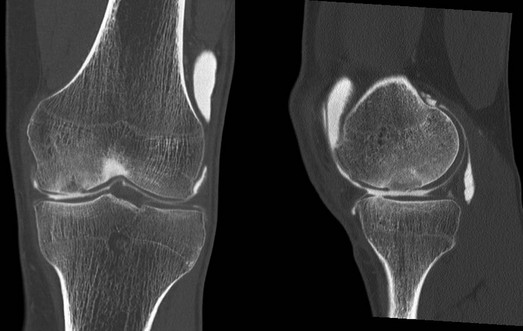

Chapter 63 Osteochondral allografting in the knee has been used for more than 20 years to reconstruct osteochondral defects resulting from trauma, malignant disease, and developmental disorders.14 In current practice, osteochondral allografts are most commonly used for the treatment of symptomatic osteochondritis dissecans and other chondral lesions that have failed primary treatment, such as internal fixation of osteochondritis dissecans fragments, marrow stimulation, mosaicplasty, and autologous chondrocyte implantation. Increasingly, allografts are now also being used as the primary treatment in situations in which other restorative procedures have demonstrated limited success, such as in the very large or uncontained defect and in the older population of patients. Although use of the procedure was initially limited by the low number of available grafts, fresh allograft tissue is becoming increasingly available as a result of improved harvesting and storage protocols, but the supply is still outpaced by a rapidly increasing demand. Evaluate the extent and depth of osseous involvement. Beware of high sensitivity for subchondral edema, which leads to false positives for osseous disease. Computed tomography (CT) scan, especially when combined with arthrography, can provide very high resolution for both cartilage and subchondral bone (Fig. 63-2). This can be particularly helpful to evaluate for subchondral sclerosis and cysts that might have to be addressed by bone grafting. The typical candidate for osteochondral allografting has a large full-thickness chondral or osteochondral defect; prior procedures, such as the repair of an unstable osteochondritis dissecans lesion, microfracture, osteochondral autograft transfer, and autologous chondrocyte implantation, have failed. Some lesions preclude the use of other cartilage repair procedures because of their large size, specific location, or associated deep osseous defects. Localized unipolar lesions larger than 2 to 3 cm2 provide an optimal environment for osteochondral grafting.1,8,9,12 Traditionally, grafts were retrieved and reimplanted fresh within 24 to 48 hours. Current standard clinical practice19 uses prolonged fresh osteochondral allografts that are stored for 2 to 4 weeks at approximately 4° C. The extended storage time allows for bacterial and viral testing before release, and also facilitates scheduling. Grafts are generally size, side, and compartment specific—for example, a left medial femoral condyle defect is treated with use of a left medial femoral hemicondyle graft. Given the popularity of the procedure, wait times for suitable grafts have increased, and the use of contralateral side and compartment grafts has become more common—for example, use of the right lateral hemicondyle to treat aforementioned left medial femoral condyle defect. Graft size is determined on preoperative MRI or CT scans, or AP and lateral radiographs obtained with sizing markers for correction of magnification. In general, size mismatch is more acceptable when the graft is larger rather than smaller than the recipient condyle. The tissue banks usually require the width of the tibial plateau, as well as the width and length of the hemicondyle. Also, it is helpful to relate the size of the defect and likely required dowel size. Although no consensus exists, we accept grafts that are smaller by 1 to 2 mm or larger by up to 5 mm.

Osteochondral Allografting in the Knee

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Imaging

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Indications and Contraindications

Allograft Preservation and Graft Sizing

Osteochondral Allografting in the Knee