Chapter 17 Osteoarthritis

KEY POINTS

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common condition, particularly in older adults affecting the joints such as the knee, hip, hand and foot.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common condition, particularly in older adults affecting the joints such as the knee, hip, hand and foot. As the population ages in the western world the proportion of people with OA in the population is increasing. The impact of OA is significant and will be the fourth largest cause of disability by 2020.

As the population ages in the western world the proportion of people with OA in the population is increasing. The impact of OA is significant and will be the fourth largest cause of disability by 2020. Core treatments such as exercise, physical activity and information about OA are recognised as important for all patients considered to have the diagnosis, and therapists have an active role to play in the management of people with OA.

Core treatments such as exercise, physical activity and information about OA are recognised as important for all patients considered to have the diagnosis, and therapists have an active role to play in the management of people with OA.INTRODUCTION

The following chapter provides an overview of osteoarthritis (OA), its impact on functioning and the effectiveness of current treatments, including prevention efforts. OA is a complex disorder. The most commonly affected sites are the knees, hips and hands, followed by other areas such as the low back, neck and feet (Dieppe & Lohmander 2005). OA causes pain, stiffness and disability. Structures in and around the joint are considered to be the primary cause of signs and symptoms (Felson et al 2000). It is now recognised that OA should not be considered a wear and tear disease but a dynamic process of changes within a joint followed by repair and remodelling (Doherty & Dougados 2001). OA develops when excessive mechanical loads are placed on normal joints, when normal loads are placed on an abnormal joint (Brandt et al 2006), or where there is an inherent susceptibility for acquiring OA.

RISK FACTORS

Whilst there is no one single identifiable cause of OA, a number of risk factors for the onset of OA have been identified. These include increasing age, female gender, genetics, obesity, trauma, occupational activities, and local mechanical factors (Doherty 2001, Hunter & Felson 2006).

GENETICS

There is evidence of a strong hereditary component to OA in the hand, from studies of twins, and of an increased risk of hand OA in first-degree relatives (siblings, parents, offspring) of people with hand OA (Doherty 2000). Sisters of women with Heberden’s nodes are more likely than expected to have Heberden’s nodes themselves in their fifties (Stecher 1941). Early changes in the knee joint such as loss of medial cartilage volume and muscle strength have been found to have a high hereditary component (Zhai et al 2005).

OBESITY

Being overweight has been found to precede the development of knee OA (Felson et al 1997). Obesity increases the mechanical load on the knee joint and being overweight also increases the risk of disease progression (Dougados et al 1992, Schouten et al 1992).

TRAUMA

A previous injury to knee, hip or hand joints has been associated with development of OA (Dieppe & Lohmander 2005).

OCCUPATIONAL FACTORS

Specific jobs are associated with development of OA. Jobs which require repetitive pincer motions have been associated with OA of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (Hadler et al 1978). Other jobs, such as farming, that require squatting and kneeling along with heavy lifting have been associated with knee and hip OA (Croft et al 1992).

LOCAL MECHANICAL FACTORS

In knee OA, the malalignment of the hip, knee, and ankle (an angle measured by full-limb radiography) has been shown to be a predictor of OA progression (Issa & Sharma 2006). Malalignment can be either varus (bow-legged) or valgus (knock-kneed) (Issa & Sharma 2006) and depending upon the type of malalignment, knee OA progression is higher in specific compartments of the knee joint (Sharma et al 2001).

PREVALENCE AND INCIDENCE

Arthritis affects approximately 43 million adults in the USA and is a leading cause of disability (Center for Disease Control 2001, Hootman et al 2005). A report by Arthritis Care (2004) identified 8.5 million adults in the UK with pain and disability that could be attributed to arthritis, with OA the most common form of all the arthritis conditions.

OA generally affects more females than males, (Felson et al 1987, Lawrence et al 1998, van Saase et al 1989) however, a recent meta-analysis showed that these gender differences may be dependent on the joint site. Specifically, females tended to show a higher prevalence of knee and hand OA compared to men but no differences were found in prevalence of hip OA (Srikanth et al 2005).

The prevalence of OA increases with age as OA is irreversible. Approximately 10% of the world’s population over 60 years will have symptoms that can be attributed to OA (Symmons et al 2003). Based on estimates from US population data, nearly everyone over the age of 65 years will have at least minimal radiographic signs of osteoarthritis at one joint site (Lawrence et al 1998). There have been very few studies of the incidence of OA despite this being the commonest form of arthritis. Oliveria et al (1999) report the incidence of OA to be 671 in women and 399 in men per 100,000 adults.

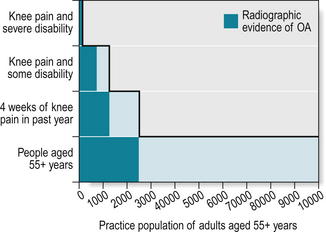

OA is often asymptomatic in individuals, but by far the most common symptom that leads an individual to seek a diagnosis and treatment is pain. Figure 17.1 describes a ‘staircase’ of the prevalence of OA of the knee presenting in primary care (Peat et al 2001). It shows how the association between joint signs on x-ray and joint pain experienced strengthens as people progress up the ‘staircase’.

MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY

OA is common in older adults and as the western population increases in age the proportion of people with OA in the community will increase. It has been estimated that OA will be the fourth leading cause of disability by 2020 and the 6th leading cause of years lived with disability (Woolf & Pfleger 2003).

GLOBAL IMPACT

In the UK in 1999–2000, 36 million working days were lost due to OA, at a cost of £3.2 billion in lost productivity (Department for Work and Pensions cited in: Arthritis Research Campaign 2002). At this time, £43 million was also spent on community services and £215 million was spent on social services tackling OA-related problems (ARMA 2004). The total cost of OA in the UK has been estimated to be equivalent of 1% of Gross National Productivity per year (ARMA 2004, Doherty et al 2003, Levy et al 1993).

Arthritis treatment is associated with a large economic burden on the US healthcare system (estimated at $86 billion in 1997) (Murphy et al 2004). This burden is likely to become even greater with the projected increase of arthritis to 20% of the US population by 2030 (Center for Disease Control 2003).

AETIOLOGY, PATHOLOGY, IMMUNOLOGY

The pathophysiological changes in OA are considered to be dynamic. In OA, there is focal loss of cartilage covering the bone ends of the synovial joint with associated changes underneath the cartilage (subchondral) and formation of bone growths called osteophytes (Dieppe & Lohmander 2005). As the disease progresses, fluid filled cysts form in the bone, and fragments of bone or cartilage may float loosely in the joint space. The synovium also can become inflamed in advanced stages of the disease, which can further irritate the cartilage.

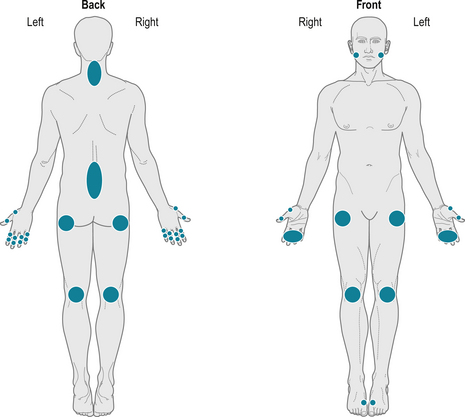

It has been suggested that OA may be classified based on potential cause; primary and secondary (Mitchell & Cruess 1977). Primary OA is more of a ‘generalised’ disease arising from systemic or genetic predisposition (Fig. 17.2). Secondary OA is a ‘local’ disease in which there is a definite history of injury or trauma to a particular joint (Felson et al 2000). Local OA, such as OA of the knee, is often seen in athletes and people at younger ages while primary OA, in which one or more joints are affected, is most prevalent among older adults.

DISEASE ACTIVITY, PROGRESSION, PROGNOSIS, INFLAMMATION

OA is commonly known as a non-inflammatory condition, however, it is increasingly recognised that variable degrees of local inflammation can occur (Symmons et al 2003) and that treatment approaches targeted at inflammation may be appropriate at certain stages of the disease (NICE 2008, Zhang et al 2007a, 2007b).

DIAGNOSIS, DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS, SPECIAL TESTS

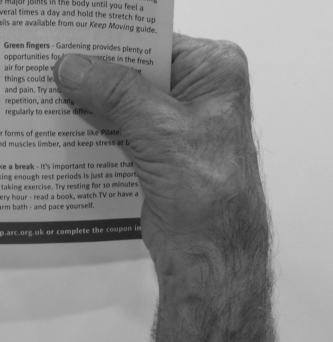

Whilst it is recognised that asymptomatic radiographic OA exists, in clinical practice patients frequently present with symptomatic joints with or without accompanying changes on X-ray. OA pain may be accompanied by morning stiffness, which occurs on first wakening in the morning and lasts less than 30 minutes. The sensation of joint stiffness can also be present when mobilising after resting for a prolonged period of time. The hip, knee (tibiofemoral, tibia and patellofemoral joints) and hand (carpometacarpal joint, distal interphalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints) are the most frequently affected sites. In the hands, nodes, which were first described by William Heberden (1710–1801) can be present. If nodes are present in the distal interphalangeal joints they are classed as Heberden’s nodes (Fig. 17.3) and in the proximal interphalangeal joints, Bouchard’s nodes.

OA is diagnosed either by X-ray, clinical examination, or a combination of the two. Radiographic confirmation of OA involves examination of the presence of joint changes and severity of the disease and is often measured on the Kellgren and Lawrence scale (Box 17.1) (Kellgren & Lawrence 1957).

BOX 17.1 Kellgren Lawrence Scale for describing radiographic OA (Kellgren & Lawrence 1957)

| 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Doubtful joint space narrowing and possible osteophytes |

| 2 | Definite osteophytes and possible joint space narrowing |

| 3 | Moderate multiple osteophytes, definite joint space narrowing, some sclerosis and possible deformity of bone ends |

| 4 | Large osteophytes, marked joint space narrowing, severe sclerosis and definite deformity of bone ends |

Some studies have found that radiographic severity of OA is not highly correlated with joint pain, (Birrell et al 2005, Hannan et al 2000) therefore a clinical examination is recommended (ARMA 2004). The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has established clinical criteria used to classify knee, hip and hand OA for research studies which includes symptoms as well as joint changes. To establish knee OA according to the ACR clinical criteria, patients need to report knee pain and have 3 of the 6 following criteria:

To establish hip OA, patients need to report hip pain and have either:

To establish hand OA, patients need to meet the following criteria:

The 10 selected joints are the CMCJ, index and middle finger – DIPJs and PIPJs – on each hand.

In primary care the use of X-rays to establish a diagnosis of OA is limited (NICE 2008) as this does not direct future management in this setting. Whilst initial studies provided support for the use of clinical criteria to classify OA without radiographs, a recent study found that in the knee the criteria may only be sensitive in detecting later stages of OA (Peat et al 2006). X-ray is often still considered the gold standard in OA diagnosis (Altman et al 1986 & 1991).

A differential diagnosis is helpful to exclude patients who have inflammatory arthritis. No special laboratory tests are indicated to confirm OA but patients who have suspected inflammatory arthritis may need blood tests to rule out these conditions (Zhang et al 2009). As OA affects a high proportion of older adults, it is essential to recognise that such individuals may also have a number of co-existing conditions e.g. cardiovascular problems, diabetes (Kadam et al 2004).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION, CLINICAL FEATURES, CLINICAL SUBSETS

Joint pain in older people can be attributed to the joint itself and/or structures supporting the surrounding joint. The cartilage and underlying bone are degraded by the process of OA and whilst cartilage does not contain nerve endings that may generate pain the underlying bone does. Figure 17.4 illustrates the common sites that may be affected in isolation, bilaterally or in combination.

Different sub-sets of OA have been identified in the literature. Often a number of joints are affected. For instance, it is projected that up to 50% of people with knee or hip OA also have back pain (Wolfe et al 1996a). Generalised OA describes multi-site involvement. Nodal OA involves nodes at the IP joints of the hands in combination with OA at other sites. Erosive hand OA has been defined radiographically, where severe destruction of a joint and erosions can be identified. This form of OA is considered aggressive and disabling (Punzi et al 2004, Verbruggen & Veys 2000). Thumb base involvement is considered to have more severe functional consequences in hand OA (Zhang et al 2009).

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

The following section covers the predominant symptoms and signs of OA.

PAIN

In the knee or hip, pain may also be felt during activities such as bending or stair climbing. Another source of OA pain may result from altering movement patterns to favour the less affected knee or hip. In this case, controlateral muscle pain may be felt. The unpredictability of intermittent pain in the lower limb often has a greater impact on the individual than constant pain (Hawker et al 2008).

FATIGUE

Fatigue is an understudied but prevalent symptom in OA. It is associated with decreased physical function and disability in mobility activities (Avlund et al 2003, Wolfe 1999). Fatigue is also highly associated with pain (Wolfe et al 1996b, Zautra et al 2007). The mechanisms of fatigue, however, in people with OA remain unclear. In knee OA, it is hypothesized that quadriceps fatigue during prolonged walking in older, obese people may contribute to OA development and progression (Syed & Davis 2000). The experience of fatigue is likely to be multi-faceted for people with OA. For instance, people who have higher daily fatigue are found to have less positive emotions within the day (Zautra et al 2007) and decreased physical activity (Murphy et al 2008). Whereas OA pain has been well studied, future work will need to examine the symptom of fatigue in OA in order to best refine treatment strategies.

JOINT ENLARGEMENT AND NODES

Joint enlargement is one of the hallmarks of OA, however the reliability of clinical assessment of joint enlargement is variable. The clinical classification of hand OA using the ACR clinical criteria (Altman et al 1990) uses joint enlargement as a feature to distinguish OA from RA. Heberden’s nodes are found at the DIP joints and are seen as pea-like structures on the dorsolateral aspect of the joint (Fig. 17.3). Bouchards’ nodes are seen at the PIP joints. Finger nodes and joint deformities do not always cause significant pain or disability however they might cause dissatisfaction with hand appearance.

JOINT DEFORMITIES

Structural changes within the OA joint can lead to joint deformity. Figures 17.5 and 17.6 illustrate common joint deformities of the lower limb and hands. Malalignment can be either varus (bow-legged) or valgus (knock-kneed) (Issa & Sharma 2006). A quadriceps lag and fixed flexion deformity are features seen at the knee joint and flexion contractures may occur at the hip. Lateral deviation and flexion of the finger joints and subluxation and adduction at the thumb base are common hand deformities.

EFFUSION

Mild joint effusions in the knee are not uncommon and the prepatella and anserine bursae may show signs of inflammation (bursitis). In the hand, if more than two metacarpophalangeal joints are swollen then inflammatory arthritis should be considered (Altman et al 1990). A hot, swollen joint is a red flag for OA and warrants immediate investigation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree