Chapter 16. Osteoarthritis

Pathology

Osteoarthritis is a poor name for degenerative joint disease. Articular cartilage is involved more than bone, and inflammation is secondary to the disease and not the cause. ‘Osteoarthrosis’ is often used as an alternative and ‘osteochondrosis’ would be more accurate, but ‘osteoarthritis’ is so well established that it is unlikely to be displaced.

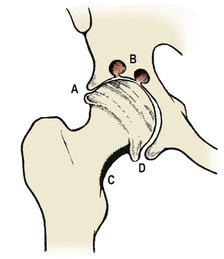

Osteoarthritis is the result of progressive breakdown of the joint surface and can follow any insult to any joint. Infection, direct or indirect trauma to the articular cartilage and joint diseases can all lead to osteoarthritis. The disease involves mainly the large weight-bearing joints. In this respect it differs from rheumatoid arthritis, which involves the synovium of many joints and is commoner in the small joints of the hands and feet (Fig. 16.1).

|

| Fig. 16.1 Some differences between rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis mainly affects the weight-bearing joints and is more common in elderly and heavyweight people. Rheumatoid arthritis affects small joints, is symmetrical and is commonest in young women. |

Primary osteoarthritis includes several different conditions, the commonest of which is generalized nodal osteoarthritis. White women are most often affected, during the fifth and sixth decades, by polyarticular involvement of many joints. The onset can be relatively sudden with hot, inflamed, distal interphalangeal joints.

Hip disease behaves differently. The condition is more common in men, is often unilateral with no other joint involvement and may have no obvious precipitating cause.

Secondary osteoarthritis has many causes, of which the commonest are:

1. Obesity.

2. Abnormal contour of the articular surfaces, particularly malunited fractures.

3. Malalignment of the joints from deformity, fracture or the distortion of the anatomy by previous surgery, particularly meniscectomy at the knee.

4. Joint instability due to trauma or generalized ligamentous laxity.

5. Genetic or developmental abnormalities, such as epiphyseal dysplasia, Perthes disease or slipped epiphysis.

6. Metabolic or endocrine disease, including ochronosis (alkaptonuria), acromegaly and the mucopolysaccharidoses.

8. Osteonecrosis.

9. The neuropathies, especially denervated joints and Charcot’s disease.

In short, any joint disease can cause osteoarthritis!

The development of osteoarthrosis can be considered in five stages:

1. Breakdown of articular surface.

2. Synovial irritation.

3. Remodelling.

4. Eburnation of bone and cyst formation.

5. Disorganization.

Breakdown of articular surface

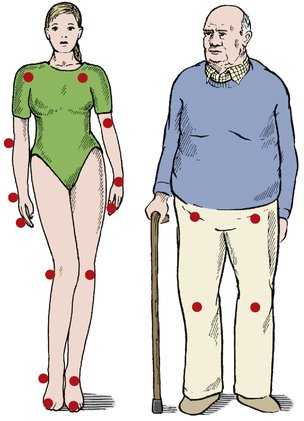

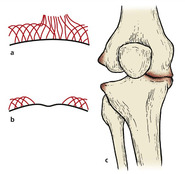

Degenerative osteoarthritis begins with failure of the articular surface (Fig. 16.2). The normal smooth surface of articular cartilage is breached, the arcades of collagen fibres break and the surface becomes rough, like a shaggy carpet. Friction against the rough surface generates particles of articular cartilage that are shed into the joint and absorbed by the synovium, where they cause an inflammatory response which the patient feels as stiffness or aching in the joint after exercise rather than at the time of use.

|

| Fig. 16.2 The development of osteoarthritis: (a) breakdown of the articular surface with rupture of the collagen arcades; (b) exposed bone with eburnation; (c) deformity and collapse. |

Synovial irritation

The irritation of the synovium is probably due to the release of intracellular enzymes, including lysozymes, which produce hyperaemia and a cellular response in the synovial layers. The synovium can also produce degradative enzymes and mediators such as interleukin-1, which may influence chondrocyte activity. Other potential causes of damage include free radicals and the deposition of immune complexes.

Remodelling

Limited cartilage repair can occur. Superficial lesions of articular cartilage show little healing but deep lesions that penetrate cortical bone allow the influx of marrow cells and the formation of fibrocartilage. Hyaline cartilage, however, is a once-in-a-lifetime tissue and does not regenerate.

The subchondral bone is also abnormally active, with an increase in both the density of the tissue and the number of cells. At the margin of the joint, new bone forms as osteophytes covered by fibrocartilage, perhaps induced by wear particles swept to the edge of the joint by joint movement. There, the osteophytes restrict joint movement.

A line of dense, hard, resilient bone forms just below the cartilage and the joint ‘remodels’ so that there is a change in shape and congruity. This alters the pattern of weight-bearing, which in turn means that the load is taken by different areas of articular cartilage.

Eburnation of bone and cyst formation

If the joint is rested, the wear particles are gradually absorbed. Fibrous tissue may form in the defect on the joint surface but as time goes by this repair process gradually fails and the articular surface is eroded to expose subchondral bone, which subsequently becomes polished and eburnated.

Raw bone rubbing against raw bone is painful. The eburnated bone is not as slippery as healthy articular cartilage, friction across the joint is increased and weight transmission across the joint becomes uneven. This change overloads some parts of the joint surface and microfractures occur in the trabeculae of the cancellous bone.

The microfractures heal with callus, which increases the rigidity of the bone so that the bone gradually becomes denser, more sclerotic and less resilient. This, in turn, causes more microfractures and the normal architecture of the bone is lost.

At this stage, synovial fluid enters the cancellous bone under pressure through cracks in the articular surface, producing cavities that are seen radiologically as ‘cysts’. These cysts fill with fibrous tissue and become lined with a thin shell of cortical bone.

Disorganization

As the disease advances, the joint becomes progressively stiffer and more deformed as the osteophytes enlarge and the bone surfaces are worn away. The ball and socket of the hip is gradually converted into a roller bearing and hinge joints develop a valgus or varus deformity as one side is worn away.

As bone is lost the ligaments become looser, not because they lengthen but because the bones that they support become shorter.

Radiological appearance

The radiological appearance of osteoarthritis reflects these pathological changes (Fig. 16.3). The joint spaces narrow, the weight-bearing surface becomes sclerotic, osteophytes form around the joint margins and cysts are seen in the subchondral bone. The shape of the bone slowly alters and this deformity can be seen radiologically as well as clinically (Fig. 16.4).